9.9 SOCIOCULTURAL ISSUES

Most countries in East Asia have one dominant ethnic group, but all countries have considerable cultural diversity. In China, for example, 93 percent of Chinese citizens call themselves “people of the Han.” The name harks back about 2000 years to the Han empire but it gained currency only in the early twentieth century, when nationalist leaders were trying to create a mass Chinese identity. The term Han simply connotes people who share a general way of life and pride in Chinese culture. The main language spoken by the Han is Mandarin, although it is only one of many Chinese dialects.

China’s non-

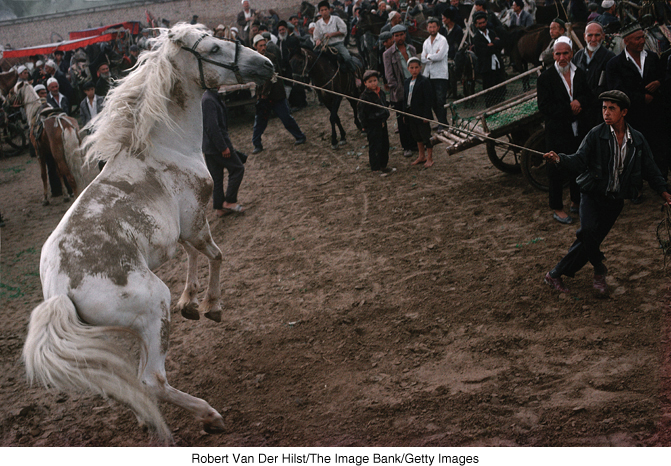

Western China’s Muslims Muslims of various ethnic origins have long been prominent minorities in China. All are originally of Central Asian origin and most are Turkic people who historically have been nomadic herders. Others specialized in trading. They tend to be concentrated in China’s northwest and often think of themselves as quite separate from mainstream China.

Uygurs (pronounced WEE-

The Beijing government claims this area’s oil, other mineral resources, and irrigable agricultural land for national development. Accordingly, it has sent troops and many millions of Han settlers to Xinjiang through what is known as the “Go West” policy. The Han settlers fill most managerial jobs in the bureaucracy, mineral extraction, the military, and power generation. An important secondary role of the Han is to dilute the power of Uygurs and Kazakhs within their own lands. In Xinjiang, there are now almost as many Han as Uygurs (8 versus 9 million), plus small numbers of other minorities.

The Beijing government has rushed to develop Xinjiang and its capital Urumqi by making special development zones (ETDZs) in the area, but the Uygurs have been left out of most policy-

Until recently, the Uygur people of Xinjiang expressed their resistance to Han dominance merely by reinvigorating their Islamic culture. Islamic prayers were increasingly heard publicly, more Muslim women were wearing Islamic dress, Uygur was spoken rather than Chinese, and Islamic architectural traditions were being revived. Then more active resistance groups, formed by Uygur separatists, began carrying out attacks on Chinese targets. In 2009, violence erupted in the streets of Urumqi between Uygurs and the Han, and about 200 people were killed. The Beijing government responded by harshly punishing the rioters and broadcasting the accusation that all Uygur separatists, even those committed to nonviolence, are Islamic fundamentalists bent on terrorism. In 2013, China’s government began arresting nonviolent Uygur Internet-

Distinct from the Uygurs and Kazakhs are the Hui, who altogether number about 10 million. The original Hui people were descended from ancient Turkic Muslim traders who traveled the Silk Road from Europe across Central Asia to Kashgar (now Kashi) and on to Xian in the east (see the map of the Silk Road in Figure 5.9; see also Figure 9.27). Subgroups of Hui live in the Ningxia Huizu Autonomous Region and throughout northern, western, and southwestern China. There they continue as traders, farmers, and artisans. The tradition of commercial activity and adoption of the Chinese language among the Hui has facilitated their success in China. Many are active in the new free market economies of southeastern China as businesspeople, technicians, and financial managers, using their money not just to buy luxury goods but also to revive religious instruction and to fund their mosques, which are now more obvious in the landscape.

The Tibetans The Tibetans, in contrast to the prosperous and assimilated Hui, are an impoverished ethnic minority group of nearly 5 million people scattered thinly over a huge, high, mountainous region in western China. The history of Tibet’s political status vis-

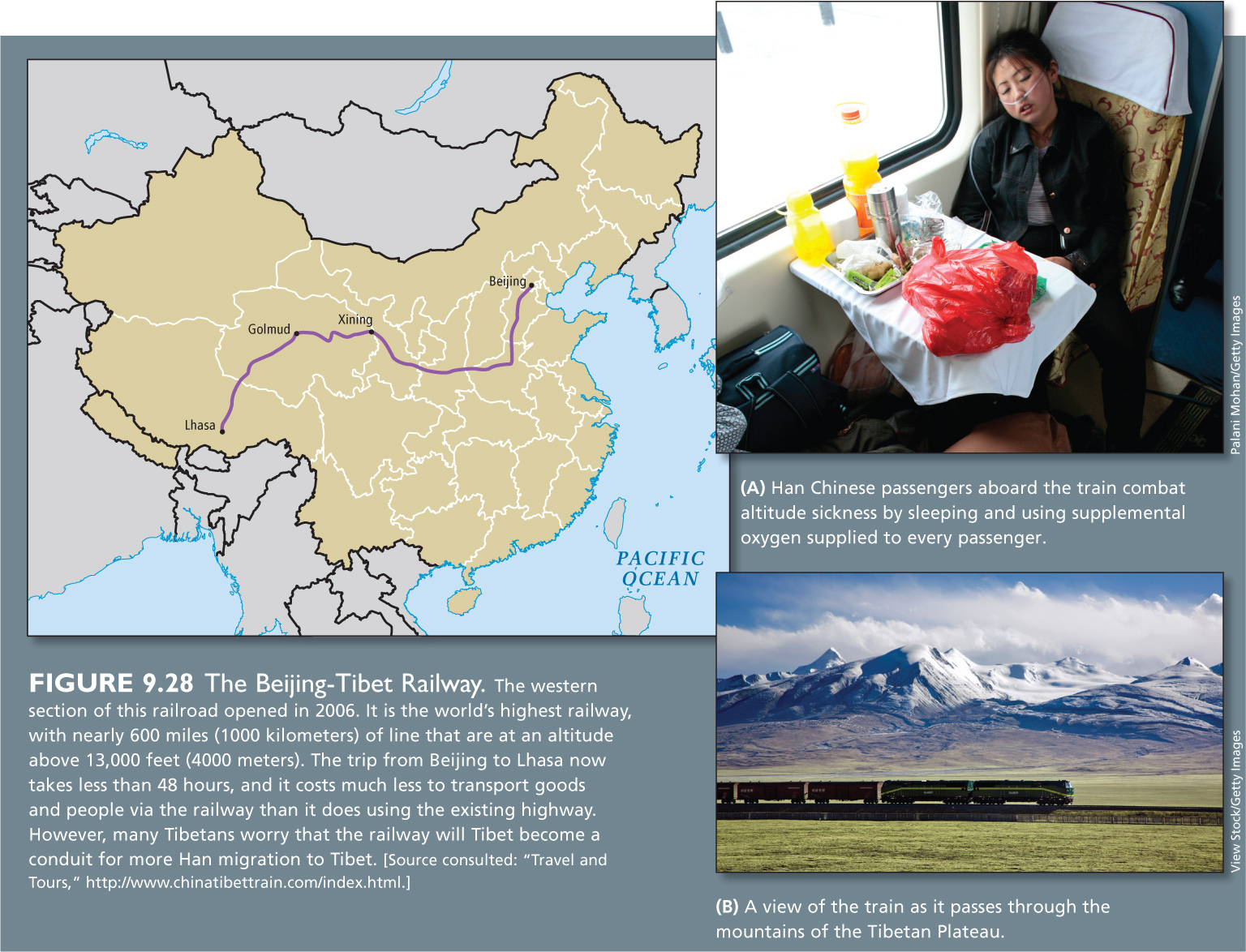

By the 1990s, the Beijing government’s strategy was to overwhelm the Tibetans with secular social and economic modernization and with Han Chinese settlers rather than outright military force (though China maintains a military presence in Tibet). To attract trade and quell foreign criticism of its treatment of Tibetans, China now spends hundreds of millions of dollars on housing and on roads, railroads, and a tourism infrastructure that capitalizes on European and American interest in Tibetan culture. China presents its actions in Tibet as part of its overall strategy to integrate the entire country economically and socially. Schools are being built and jobs opened up to young Tibetans. A new railway link connecting Tibet more conveniently to the rest of China was completed in 2006 (Figure 9.28). The Han in Tibet see the railway as a public service that will promote Tibetan development, but Tibetan activists see it as a conveyor belt for more Han dominance over the Tibetan economy and culture.  214. TIBETAN BUDDHIST NUNS’ PROTEST SONGS BRING PUNISHMENT FROM CHINA

214. TIBETAN BUDDHIST NUNS’ PROTEST SONGS BRING PUNISHMENT FROM CHINA

Within Tibetan culture, women have held a somewhat higher position than in other cultures of East Asia. Buddhism did introduce many patriarchal attitudes to Tibet, but these did not curtail other more equitable traditions. Among nomadic herders, women could have more than one husband, just as men were free to have more than one wife. At marriage, a husband often joins the wife’s family. By comparison, Han Chinese culture has typically regarded the women of Tibet and other western minorities as barbaric precisely because their roles were not circumscribed. They rode horses, they worked alongside the men in herding and agriculture, and they were generally more assertive in daily life than their Chinese counterparts.

Indigenous Diversity in Southern China In Yunnan Province in southern China, more than 20 groups of ancient native peoples live in remote areas of the deeply folded mountains that stretch into Southeast Asia. These groups speak many different languages, and many have cultural and language connections to the indigenous people of Tibet, Burma, Thailand, or Cambodia. Gender relations are different here than among the Han. A crucial difference may be that among several groups, most notably the Dai, a husband moves in with his wife’s family at marriage and provides her family with labor or income. A husband inherits from his wife’s family rather than from his birth family.

Taiwan’s Many Minorities In Taiwan and the adjacent islands, the Han account for 95 percent of the population, but Taiwan is also home to 60 indigenous minorities. Some have cultural characteristics—

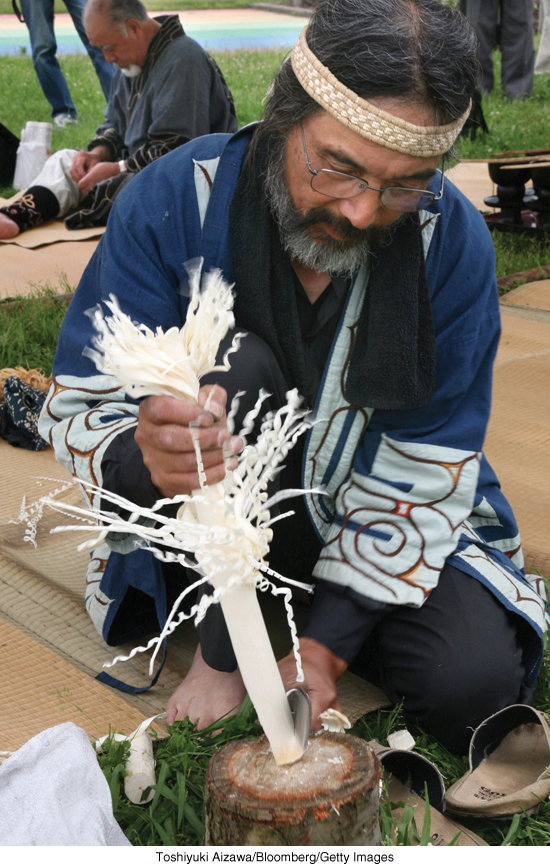

The Ainu in Japan There are several indigenous minorities in Japan and most have suffered considerable discrimination. A small and distinctive minority group is the Ainu, characterized by their light skin, heavy beards, and thick, wavy hair. Now numbering only about 30,000 to 50,000, the Ainu are a racially and culturally distinct group thought to have migrated many thousands of years ago from the northern Asian steppes. They once occupied Hokkaido and northern Honshu and lived by hunting, fishing, and some cultivation, but they are now being displaced by forestry and other development activities. Few full-

Ainu an indigenous cultural minority group in Japan characterized by their light skin, heavy beards, and thick, wavy hair, who are thought to have migrated thousands of years ago from the northern Asian steppes

East Asia’s Most Influential Cultural Export: The Overseas Chinese

China has had an impact on the rest of the world not only through its global trade, but also through the migration of its people to nearly all corners of the world. The first recorded emigration by the Chinese took place more than 2200 years ago. Following that, China’s contacts then spread eastward to Korea and Japan, westward into Central and Southwest Asia via the Silk Road, and by the fifteenth century, to Southeast Asia, coastal India, the Arabian Peninsula, and even Africa.

Trade was probably the first impetus for Chinese emigration. The early merchants, artisans, sailors, and laborers came mainly from China’s southeastern coastal provinces. Taking their families with them, some settled permanently on the peninsulas and islands of what are now Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Today they form a prosperous urban commercial class known as the Overseas Chinese. The quintessential Overseas Chinese state in Southeast Asia is Singapore, where 77 percent of the population is ethnically Chinese (see Chapter 10).

In the nineteenth century, economic hardship in China and a growing international demand for labor spawned the migration of as many as 10 million Chinese people to countries all over the world. By the middle of the twentieth century, many others fleeing the repression of China’s Communist Revolution joined those from earlier migration. As a result, “Chinatowns” are found in most major world cities. The term Overseas Chinese has been extended to apply to Chinese emigrants and their descendants in all such locations.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

There are several distinct minority groups in East Asia: the Uygurs, Kazakhs, and Tibetans in western China; the Hui, scattered throughout central China; and smaller indigenous groups in southern China, Taiwan, and Japan.

There is resentment and sometimes open resistance to Han Chinese domination in the various minority homelands.

Throughout East Asia, minorities have experienced discrimination.

Millions of Overseas Chinese live in cities and towns around the world, especially in Southeast Asia. Most have settled permanently in their foreign locations and many (perhaps most) maintain relationships with China.