Self-Efficacy: Assessing Your Own Abilities

WHAT CAN WE learn about the power of self-concept and self-esteem in our own lives from Peter Dinklage’s success? Helen Sloan/© HBO/Courtesy Everett Collection

Actor Peter Dinklage won a Golden Globe award for his portrayal of the complex Tyrion Lannister in HBO’s popular original series, Game of Thrones (Kois, 2012); he received an Emmy nomination for the same role. But there was a time when such recognition seemed far off as Dinklage attempted to jump-start an acting career while living in a rat-infested Brooklyn apartment without heat. It’s not that he didn’t have offers for decent-paying parts; it’s that he turned them down. Dinklage is a little person (diagnosed with achondroplasia—a common cause of dwarfism) who refused to play elves or leprechauns, roles that would forever tie his talents to his stature. When he played Tom Thumb in a vaudevillian play, he so impressed director Tom McCarthy that McCarthy rewrote a script for “The Station Agent” to make Dinklage the leading man. A series of roles later, Dinklage earned the success he desired without playing parts that he felt would demean him—all because he believed he could “play the romantic lead and get the girl” (quoted in Kois, 2012).

Dinklage’s experiences reveal the power of self-efficacy, which is the third factor influencing our cognitions about ourselves. Like Dinklage, you have an overall view of all aspects of yourself (self-concept), as well as an evaluation of how you feel about yourself in a particular area at any given moment in time (self-esteem). Based on this information, you approach a communication situation with an eye toward the likelihood of presenting yourself effectively. This ability to predict actual success from self-concept and self-esteem is self-efficacy (Bandura, 1982). Your perceptions of self-efficacy guide your ultimate choice of communication situations, making you much more likely to engage in communication when you believe you will probably be successful and avoid situations where you believe your self-efficacy to be low.

Even though a person’s lack of effort is most often caused by perceptions of low self-efficacy, people with very high levels of self-efficacy sometimes become overconfident (Bandura, 1982; Harris & Hahn, 2011). For example, some students believe that if they understood their professors’ lectures well while sitting in class, then they wouldn’t really need to study their notes very much after that to prepare for exams. Those students often end up shocked later at how much information they did not remember.

Self-fulfilling prophecies are deeply tied to verbal and nonverbal communication. If you believe you will ace a job interview because you are well prepared, you will likely stand tall and make confident eye contact with your interviewer (Chapter 3) and use appropriate and effective language (Chapter 4) to describe your skill set. Your confidence just may land you the position you want!

Self-efficacy affects your ability to cope with failure and stress. Feelings of low self-efficacy may cause you to dwell on your shortcomings. If you already feel inadequate and then fail at something, a snowball effect occurs as the failure takes a toll on your self-esteem; stress and negative feelings result, lowering your feelings of self-efficacy even more. For example, Jessie is job hunting but worries that she does not do well in interviews. Every time she goes to an interview and then doesn’t get a job offer, her self-efficacy drops. She lowers her expectations for herself, and her interview performance worsens as well. By contrast, people with high self-efficacy are less emotionally battered by failures because they usually chalk up disappointments to a “bad day” or some other external factor.

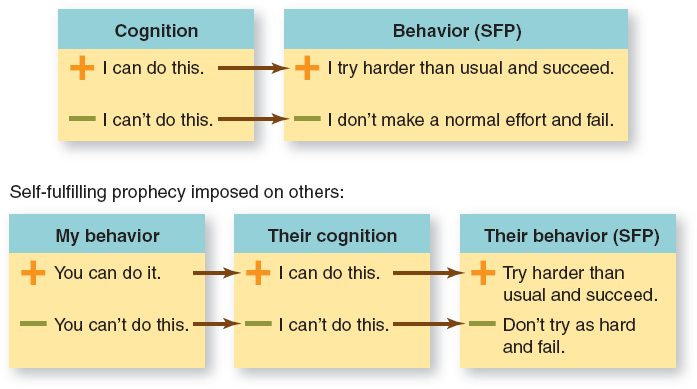

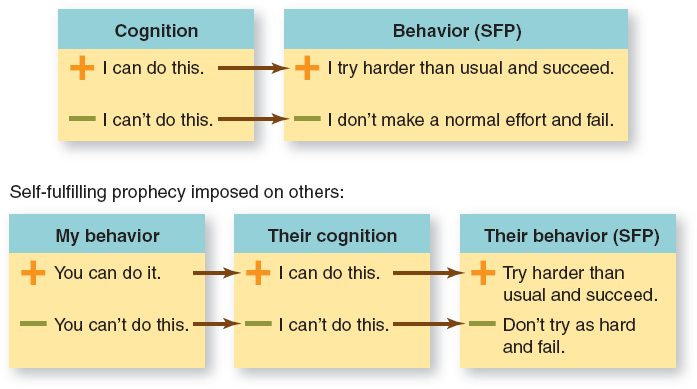

Perceptions of your self-efficacy may lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy—a prediction that causes you to change your behavior in a way that makes the prediction more likely to occur. If you go to a party believing that others don’t enjoy your company, for example, you’ll probably stand apart, not talking to anyone and making no effort to be friendly. Others won’t like you, so your prophecy gets fulfilled. Self-efficacy and self-fulfilling prophecy are thus related. Low self-efficacy often causes you to exert less effort to prepare or participate than you would in situations in which you are comfortable and have high self-efficacy. When you do not prepare for or participate in a situation (such as at the party), your behavior causes the prediction to come true, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy (see Figure 2.3). One study of international soccer tournaments found teams that had a history of losing (even if the current players were not a part of the losing effort) were significantly less likely to win the penalty shoot-outs that decide a tied game (Jordet, Hartman, & Jelle Vuijk, 2012). Why? It’s possible that the players choked under a high degree of performance pressure, unable to predict their own success from past performances. It is also possible that they hurried their preparation and thus created their own demise.

Figure 2.3: FIGURE 2.3 THE SELF-FULFILLING PROPHECY

Self-fulfilling prophecies don’t always produce negative results. If you announce plans to improve your grades after a lackluster semester and then work harder than usual to accomplish your goal, your prediction may result in an improved GPA. But even the simple act of announcing your goals to others—for example, tweeting your intention to quit smoking or to run a marathon—can create a commitment to making a positive self-fulfilling prophecy come true (Willard & Gramzow, 2008).