8.2 Somatic Symptom Disorders

During the course of her illness, Anna O. developed medical symptoms that her doctors could not explain. For instance, she saw an eye doctor for problems with her vision, but he was unable to identify the cause (Breuer & Freud, 1895/1955). Similarly, doctors were unable to find a medical explanation for her chronic cough. How might persistent medically unexplained physical symptoms such as these arise? How should they best be treated? Such bodily symptoms (also called somatic symptoms) may fall under the category of somatic symptom disorders in DSM-5.

Somatic Symptom Disorders: An Overview

Somatic symptom disorders A category of psychological disorders characterized by symptoms about physical well-being along with cognitive distortions about bodily symptoms and their meaning; the focus on these bodily symptoms causes significant distress or impaired functioning.

The hallmark of somatic symptom disorders is complaints about physical well-being along with cognitive distortions about bodily symptoms and their meaning; the focus on these bodily symptoms causes significant distress or impaired functioning. With these disorders, it is the person’s response to bodily symptoms that is notable and excessive. Common bodily complaints of patients with somatic symptom disorders are listed in TABLE 8.7.

|

| Source: Mayou & Farmer, 2002. For more information see the Permissions section. |

Somatic symptom disorders are relatively rare in the general population but are the most common type of psychological disorder in medical settings (Bass et al., 2001). The medical costs of caring for patients with somatic symptom disorders are substantial; according to one estimate, these costs come to over $250 billion each year in the United States alone (Barsky et al., 2005).

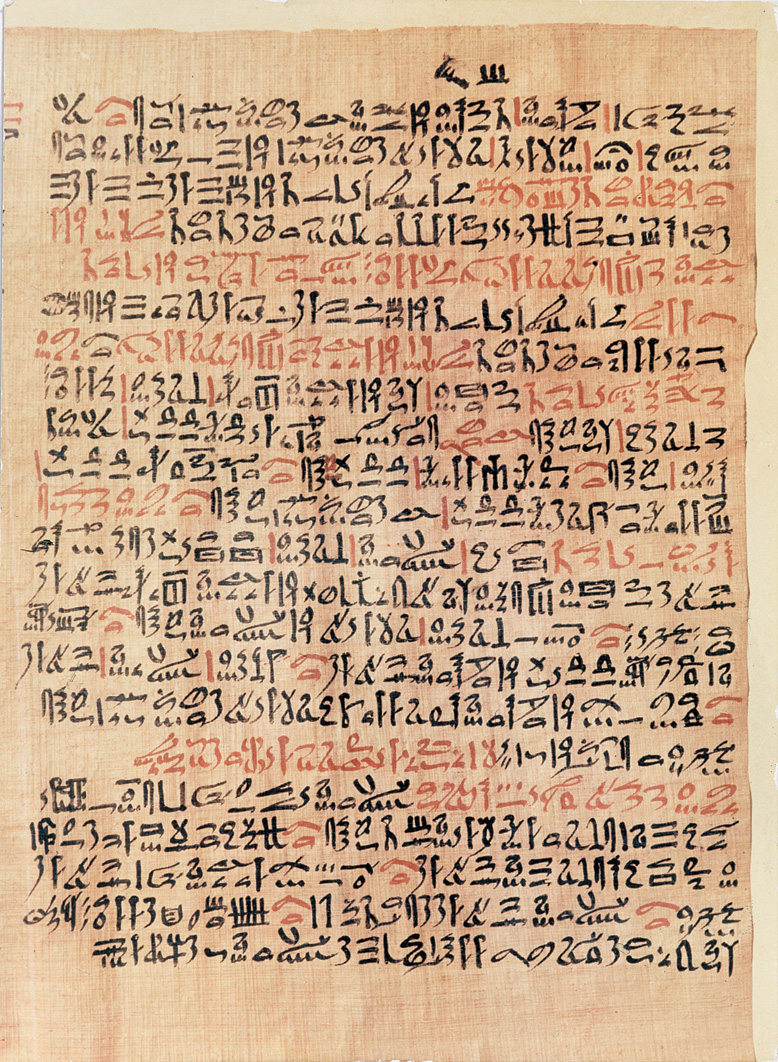

Somatic symptom disorders are not new phenomena; they have a long history, although different labels have been given to them over time. They were described by the ancient Greek philosopher Hippocrates, who thought that somatic symptoms—generally reported by women—were caused by a wandering uterus, from which the term hysteria is derived (hystera is Greek for “uterus”; Phillips, 2001). Hysteria was often used to refer to bodily symptoms that lack a medical explanation, as was true of Anna O.; in addition, patients with hysteria typically describe their symptoms dramatically.

One somatic symptom disorder that must be distinguished from the others is factitious disorder, mentioned in Chapter 3, in which people intentionally induce symptoms or falsely report symptoms that they do not in fact have in order to receive attention from others. People who have any of the other somatic symptom disorders neither pretend to have symptoms nor intentionally induce physical symptoms for any type of gain. (However, in DSM-5, factitious disorder is considered a somatic symptom disorder because bodily symptoms may be among those feigned.)

Putting aside factitious disorder, somatic symptom disorders share two common features (Looper & Kirmayer, 2002):

- bodily preoccupation, which is similar to the heightened awareness of panic-related bodily sensations experienced by people with panic disorder (see Chapter 6), except that with somatic symptom disorders, the patient can be preoccupied with any aspect of bodily functioning; and

- symptom amplification, or directing attention to bodily symptoms such as those in TABLE 8.7, which in turn intensifies the symptoms (Kirmayer & Looper, 2006; Looper & Kirmayer, 2002). A common example of symptom amplification occurs when someone with a headache pays attention to the headache—and, invariably, the pain worsens.

In the following sections, we focus on three of these disorders in turn—somatic symptom disorder, conversion disorder, and illness anxiety disorder.

Somatic Symptom Disorder

Somatic symptom disorder (SSD) A somatic symptom disorder characterized by at least one somatic symptom that is distressing or disrupts daily life, about which the person has excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors.

The hallmark of somatic symptom disorder (SSD) is at least one somatic symptom that is distressing or disrupts daily life, about which the person has excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). For example, Anna O.’s eye problems and her cough were both physical symptoms that disrupted her daily life. Because the name of the disorder and this category of disorders are so similar (the former is singular and the latter plural), we will abbreviate the disorder as SSD.

What Is Somatic Symptom Disorder?

To be diagnosed with SSD according to DSM-5 criteria, the person must have at least one distressing or impairing bodily symptom and respond excessively to it. Examples of an excessive response are unrealistic thoughts about the seriousness of the symptoms, significant anxiety about the symptoms or health in general, or devoting excessive amount of time and energy to it—such as seeing multiple doctors when such visits aren’t necessary. For instance, a man who had a heart attack might become preoccupied with his heart rate and be afraid to go up and down stairs, lest he increase his heart rate and have another heart attack—despite his doctor’s assuring him that walking on stairs would be okay. Sometimes the single bodily symptom is pain (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). TABLE 8.8 lists the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for SSD.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

A clinician diagnoses SSD only if the person’s response to the symptoms is more extreme than what would be expected based on the medical assessment. SSD must be distinguished from various other disorders, including anxiety disorders. Many laboratory tests and visits to doctors may be required to rule out other medical and psychological diagnoses, which is necessary before a diagnosis of SSD can be made (Hilty et al., 2001). TABLE 8.9 lists additional facts about SSD.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source is American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

People with SSD may avoid certain activities that they believe are associated with their bodily symptoms, such as any type of exercise. In so doing, patients attempt to minimize the physical sensations associated with the disorder. As a result, they may become so out of shape that even normal daily activities, such as walking to a store from the parking lot, may lead them to experience bodily symptoms—which creates a vicious cycle of avoidance and increased bodily symptoms, impairing daily life. For people with SSD, these symptoms impair daily life, which is what happened to Edward in Case 8.4.

CASE 8.4 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Somatic Symptom Disorder

As an infant, Edward had scarlet fever and a mild form of epilepsy, from which he recovered. By school age, he was complaining of stomachaches and joint pain and often missed school. There were many doctors, but no dire diagnosis: Edward was healthy, but many commented, a somewhat lonely and serious little boy.

Through high school and college Edward capitalized on those traits, achieving high grades and going into the insurance business. At forty-five, he is plagued by mysterious symptoms—heart palpitations, dizziness, indigestion, pain in his shoulders, back, and neck, and fatigue—and lives with his parents. His physical disabilities have made it impossible for Edward to hold a job, and his engagement was broken off. He remains on disability and spends much of his time in and out of hospitals undergoing various tests and procedures.

(Cantor, 1996, p. 54)

Understanding Somatic Symptom Disorder

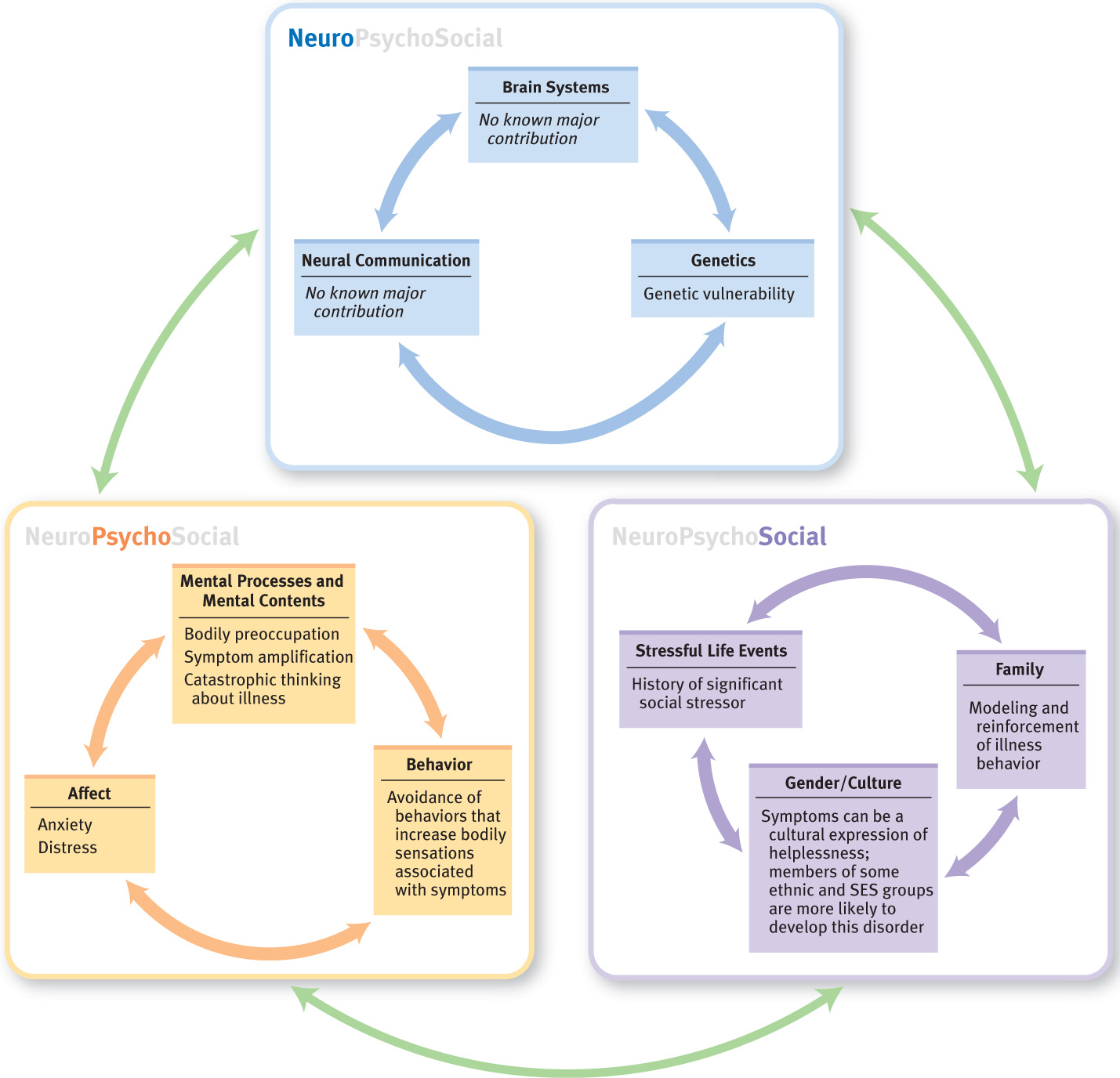

SSD can be fully understood only by considering multiple factors, including genetics, bodily preoccupation, symptom amplification and catastrophic thinking, and other people’s responses to illness.

Neurological Factors: Genetics

Most of the progress in understanding the neurological factors that underlie SSD has been in the area of genetics. For example, in a large-scale twin study, researchers found that genetic effects may account for as much as half of the variability in SSD (Kendler, Walters, et al., 1995). Note, however, that this finding does not imply that the disorder itself is necessarily inherited; it could be that temperament or other characteristics that are influenced by genetics predispose a person to develop the disorder in certain environments. (This same point can be made about most findings that link genes to disorders.) Kendler and colleagues (1995) also reported that characteristics of families have no consistent effect on whether members of the family develop this disorder. This finding suggests that, in addition to genes, specific experiences of a particular person—not shared experiences among members of a family—affect whether a person develops the disorder.

Psychological Factors: Misinterpretation of Bodily Signals and Coping

Like all other somatic symptom disorders, SSD involves bodily preoccupation and symptom amplification, as well as catastrophic thinking—in this case, about physical sensations or fears of illness. These patients may believe, for example, that headaches indicate a brain tumor. Their mental processes—particularly attention—focus on bodily sensations, including the beating of their hearts (Barsky, Cleary, et al., 1993, 1994), leading to symptom amplification and catastrophic thinking. These effects also arise in part from faulty beliefs about their bodies and bodily sensations. For example, people with SSD may erroneously believe that health is the absence of any uncomfortable physical sensations (Rief & Nanke, 1999). People who do not have a somatic symptom disorder do not habitually develop catastrophic misinterpretations of such sensations.

Somatic symptoms can also serve as a coping strategy, leading the person to focus attention away from a stressor and onto a bodily sensation. This observation can help to explain why somatic symptom disorders, including SSD, sometimes develop after the death of a loved one (as happened to Anna O. after her father died) or after another significant stressor (Hiller et al., 2002).

Social Factors: Observational Learning and Culture

Observational learning may also play a role in SSD. Such learning can explain the finding that people with SSD are more likely than those without the disorder to have had an ill parent (Bass & Murphy, 1995; Craig et al., 1993). In these cases, an ill parent may have inadvertently modeled illness behavior. Moreover, operant conditioning can also be at work, when people reinforce a person’s illness behavior: During the patient’s childhood, family members may have unintentionally reinforced illness behavior by paying extra attention to the child or buying special treats for the child when he or she was ill (Craig et al., 2004; Holder-Perkins & Wise, 2001). Similarly, adults with SSD may be reinforced for their symptoms by the attention of medical personnel, family, friends, or coworkers (Maldonado & Spiegel, 2001).

In addition, in many cultures—including in the United States—somatic symptoms may be regarded as an acceptable way to express helplessness, such as by those who experienced abuse during childhood (Walling et al., 1994). The use of somatic symptoms to express helplessness may explain the bodily symptoms of Anna O. and other upper-middle-class women of the Victorian era, whose lives were severely restricted by societal conventions. However, although symptoms of SSD occur around the globe, the nature of the symptoms differs across cultures. For instance, symptoms of burning hands or feet are more common in Africa and South Asia than in Europe or North America (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Feedback Loops in Understanding Somatic Symptom Disorder

ONLINE

It is common for people with SSD to have had a disease, an illness, an accident, or another form of trauma prior to developing the disorder. In fact, people with this disorder are more likely to report a history of childhood abuse than are other medical patients (Brown et al., 2005). People who are genetically predisposed to SSD (neurological factor), interpret the bodily sensations caused by an illness or accident as signaling a catastrophic illness (psychological factor). In turn, this misinterpretation may cause the person to change his or her behavior in a way that ultimately becomes dysfunctional, restricting activities and straining relationships.

Such misinterpretations may initially grow out of modeling. For example, children whose parents have chronic pain are more likely to report abdominal pain themselves and to use more pain relievers than a comparison group of children (Jamison & Walker, 1992). These children’s experiences with their ill parent (social factor) may influence their body via their brains (perhaps they have more stomach acid because they are more anxious and stressed; neurological factor), their attention to and attributions for bodily sensations (psychological factors), and their reporting of pain (social factor).

Moreover, a patient’s symptoms may have been unintentionally reinforced by friends and family members (social factor). And, as with panic disorder (see Chapter 6), the arousal that occurs in response to stress can increase troubling bodily sensations that then become the focus of preoccupations (see Figure 8.1).

Conversion Disorder

Conversion disorder A somatic symptom disorder that involves sensory or motor symptoms that are incompatible with known neurological and medical conditions.

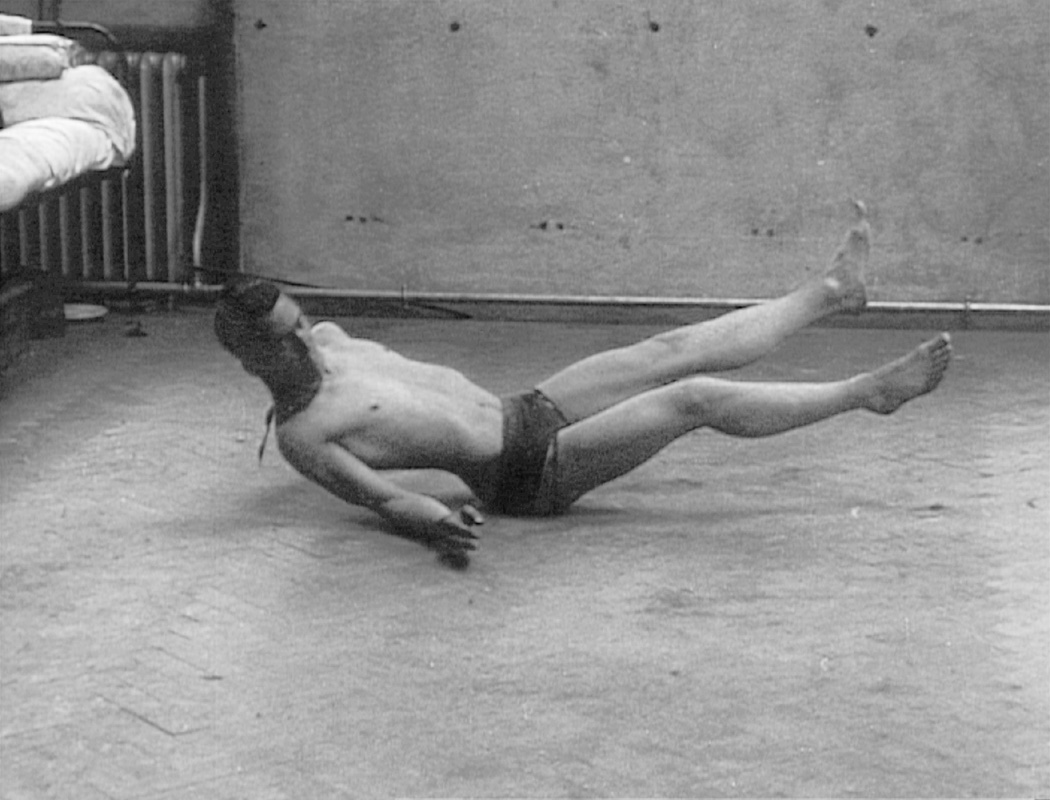

Conversion disorder involves sensory or motor symptoms that are incompatible or inconsistent with known neurological or medical conditions.

What Is Conversion Disorder?

Patients who have conversion disorder do not consciously produce the symptoms they experience (as in factitious disorder or malingering), and these patients are significantly distressed or their functioning is impaired by the symptoms (see TABLE 8.10). Conversion disorder is similar to SSD in that both involve physical symptoms; however, conversion disorder is limited to sensory and motor symptoms that appear to be neurological (that is, related to the nervous system) but, on closer examination, are inconsistent with the effects of known neurological or medical disorders (see Figure 8.2). A diagnosis of conversion disorder can be made only after physicians rule out all possible medical causes—and this process can take years. Conversion disorder is sometimes referred to as functional neurological symptom disorder because the neurological symptom relates to the functioning of some aspect of the nervous system but not to an underlying medical cause of the symptom.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

Conversion disorder is characterized by one or more of three types of symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Maldonado & Speigel, 2001):

- Motor symptoms. Examples include tremors that become worse when the person pays attention to them, tics or jerks, muscle spasms, swallowing problems, staggering, and paralysis (sometimes referred to as pseudoparalysis, which may also involve significant muscle weakness).

- Sensory symptoms. Examples include blindness, double vision, deafness, auditory hallucinations, and lack of feeling on the skin that doesn’t correspond to what is produced by malfunctioning of an actual nerve path.

- Seizures. Examples include not only the motor symptoms of twitching or jerking of some part of the body but also loss of consciousness with uncontrollable spasms of the large muscles in the body, causing the person to writhe on the floor. These seizures are often referred to as nonepileptic seizures because they do not have a neurological origin and are not usually affected by medication for seizures. The nonepileptic seizures are likely to occur when other people are present.

Anna O. had both motor conversion symptoms (paralysis of her neck, arm, and legs) and sensory conversion symptoms (problems with vision, a lack of sensation in her elbows). Breuer did not report any seizure-like symptoms.

In conversion disorder, symptoms do not correspond to what would be produced by the relevant nerve pathways, but rather they arise from the patients’ (perhaps unconscious) ideas about what would happen if certain nerve pathways were disrupted. Thus, a patient may not be able to write but can scratch an itch, which would be impossible with true paralysis of the hand muscles. Similarly, when the sensory symptom of blindness occurs in conversion disorder, medical tests reveal that all parts of the visual system function normally, as was true for Mary, described in Case 8.5.

CASE 8.5 • FROM THE INSIDE: Conversion Disorder

On graduating from high school, Mary decided to enter a convent, and by the age of 21 had taken her vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. This came as a shock to her family, who, although they were practicing Catholics, had been far from religious. “I had a great need to help people and do something spiritual and good,” Mary recalls.…

For the first decade she enjoyed the sense of community and the studious aspect of convent life…. But as time went on she became disenchanted with the church, which she felt was “out of touch with real people…. The church required blind obedience and no disagreement.”

Mary began feeling nervous and anxious. She was rarely sick, but one day [when she was 36 years old] developed soreness in the back of her eye. Every time she moved it, she’d feel pins and needles…. By the fourth day she couldn’t see out of one eye. A neurologist said it was optic neuritis, a diagnosis of nerve inflammation of unknown origin. She was hospitalized and given cortisone, but her sight didn’t improve.

…Mary took a leave of absence and spent the good part of a year at a less stressful convent in the countryside. She began meeting regularly with a psychologist…. “I discovered I was a perfectionist, overworking to avoid my growing doubts.”…Her eyesight gradually came back, and shortly after that she left the church.

…“During that period in my life I was undergoing deep psychological trauma. I was so unhappy, and I literally didn’t want to see,” she says. “I believed then, as I do today, that the body was telling me something, and I had to listen to it.”

(Cantor, 1996, pp. 57–58)

People with conversion disorder may react in radically different ways to their symptoms and to what they might imply: Some seem indifferent whereas others respond dramatically. Anna O.’s response was “a slight exaggeration, alike of cheerfulness and gloom; hence she was sometimes subject to moods” (Breuer & Freud, 1895/1955, p. 21). TABLE 8.11 provides more facts about conversion disorder.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source is American Psychiatric Association, 2000, 2013. |

Criticisms of the DSM-5 Criteria

Both the diagnosis of conversion disorder and its placement among the somatic symptom disorders are controversial (Brown & Lewis-Fernández, 2011). Some researchers have suggested that conversion disorder is not a distinct disorder but rather a variant of SSD; these researchers point out that both disorders may involve the bodily expression of psychological distress (Bourgeois et al., 2002). Other researchers believe that conversion symptoms in general, and nonepileptic seizures in particular, are more like dissociative symptoms than like symptoms of other somatic symptom disorders (Kihlstrom, 2001; Mayou et al., 2005). As they note, dissociation can not only affect memory and the sense of self but also can disrupt the integration of sensory or motor functioning.

Understanding Conversion Disorder

Research on neurological factors in conversion disorder focuses on how brain systems operate differently in people with the disorder than in other people.

Neurological Factors: Not Faking It

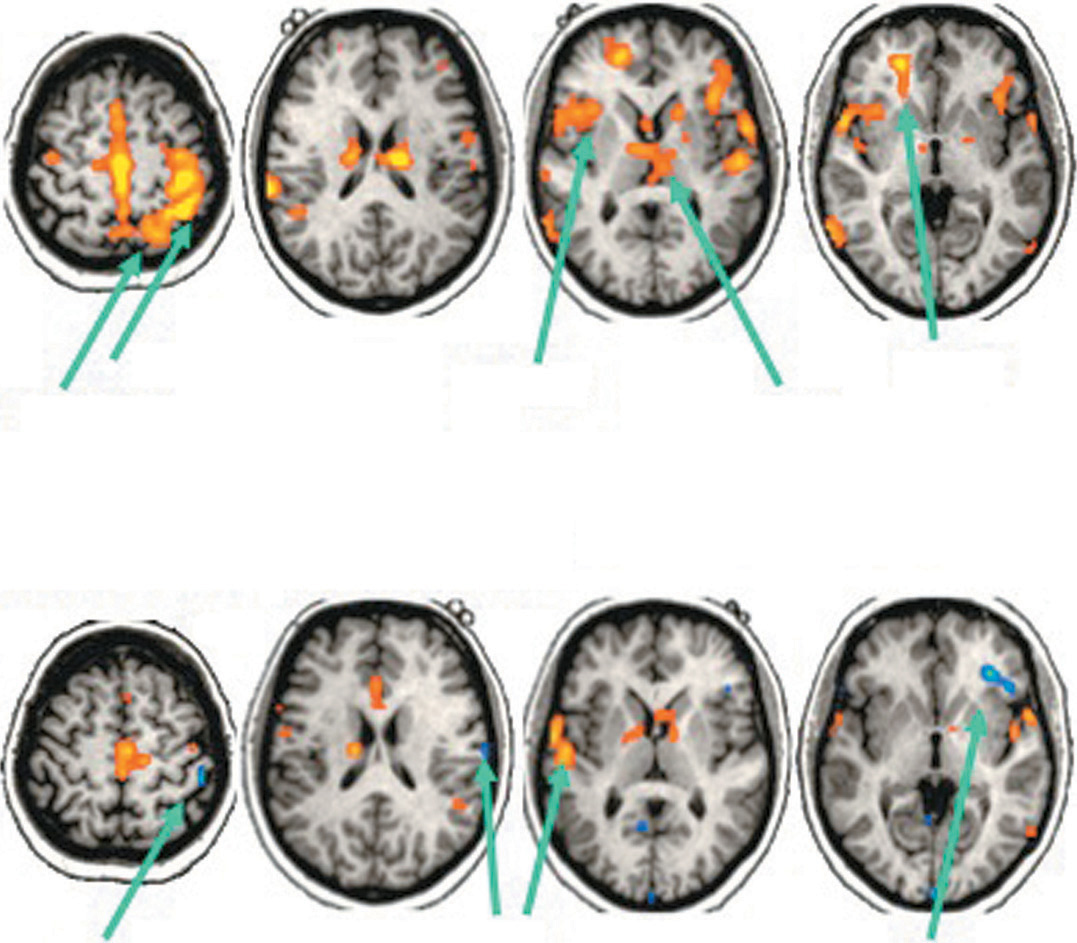

When considering making a diagnosis of conversion disorder, clinicians must rule out simple malingering, or faking of symptoms, which is difficult to do (Stone et al., 2010). Could all cases of conversion disorder just be faking? Neuroimaging findings suggest that muscle weakness arising from conversion disorder is not the same as consciously simulated muscle weakness. For example, Stone and colleagues (2007) scanned the brains of patients with conversion disorder and of healthy control participants while their ankles were flexed. The patients with conversion disorder all reported weakness in the manipulated ankle prior to the study; during the study, participants in the control group were asked to pretend that their ankles were weak. The results were clear: Some brain areas were more activated in the patients than in the controls (such as the insula, which is involved in registering bodily sensations), and some brain areas (including areas in the frontal lobes) were less activated in the patients than in the controls. These findings are good evidence that the patients in this study were not simply faking their disorder.

In addition, some patients with chronic pain develop sensory deficits, a kind of “psychological” anesthesia. In one study, researchers scanned the brains of four such patients, using fMRI, while sharp plastic fibers were pressed into the skin (Mailis-Gagnon et al., 2003). These patients had apparent sensory deficits in only one limb, and thus the researchers could directly compare stimulation of the normal and affected limbs. When the researchers stimulated the normal limb, the sharp plastic fibers activated a brain network that registers pain, as is normal. In contrast, this network was not activated when the researchers stimulated the affected limb, as is shown in Figure 8.3. These findings indicate that the “psychological” anesthesia actually affected the brain and inhibited activation in the brain areas that register sensation and pain.

Other studies have shown that conversion disorder is not a direct consequence of abnormal functioning of brain areas that register peripheral sensations but rather reflects abnormal functioning of brain areas that interpret sensations and manage other brain areas (that is, areas that are involved in “executive functions”) (Hoechstetter et al., 2002; Lorenz et al., 1998). At least in some cases, abnormal processing in brain areas responsible for executive functions might inhibit brain areas that process sensation and pain or that produce movements, which in turn causes them to fail to function properly.

Psychological Factors: Self-Hypnosis?

There is no generally accepted explanation for how psychological factors might produce the selective bodily symptoms in conversion disorder (Halligan, Athwal, et al., 2000). But self-hypnosis offers one possible explanation—that the disorder is the result of unintended self-hypnotic suggestion. According to this theory, patients have, consciously or unconsciously, “suggested” to themselves that they have symptoms (Kozlowska, 2005); that is, particular sensations have become dissociated. This theory receives support from the fact that people with conversion disorder are unusually hypnotizable (Roelofs, Hoogduin, et al., 2002) and from the finding that areas of the brain activated by hypnotically induced paralysis are similar to those activated by paralysis in patients with conversion disorder (Halligan, Bass, & Wade, 2000; Oakley, 1999).

Social Factors: Stress Response

Life stressors, such as combat, can trigger conversion disorder. Moreover, the greater the severity or number of stressors, the more severe the conversion symptoms (Roelofs et al., 2005). As we saw with SSD, somatic symptoms can be a culturally accepted way to express feelings of helplessness (Celani, 1976), which may explain why some soldiers develop conversion disorder in combat. Conversion disorder can also be a way to obtain the attention associated with being sick. This was certainly true for Anna O., as well as for many other women of the Victorian era.

Illness Anxiety Disorder

Illness anxiety disorder A somatic symptom disorder marked by a preoccupation with a fear or belief of having a serious disease in the face of either no or minor medical symptoms and excessive behaviors related to this belief.

People who are diagnosed with illness anxiety disorder have either no or minor medical symptoms but nonetheless are preoccupied with a fear or belief that they have a serious disease; they engage in excessive behaviors related to this belief, such as repeatedly checking their bodies for sign of an illness or avoiding medical care. Despite the fact that physicians cannot identify a medical problem, patients with illness anxiety disorder persist in clinging strongly to their conviction that they have a serious disease. This diagnosis is in some ways similar to the DSM-IV diagnosis of hypochondriasis. However, in DSM-IV the disorder hypochondriasis included two groups of people—those without any significant medical symptoms (now classified as illness anxiety disorder) and those with at least one medical symptom but whose psychological response to the symptom is excessive (now classified as somatic symptom disorder). Although people with SSD and those with illness anxiety disorder share a focus on bodily symptoms, only people with illness anxiety disorder believe that they have a serious illness, despite reassurance from doctors and minimal physical symptoms, if any.

CURRENT CONTROVERSY

Omission of Hypochondriasis from DSM-5: Appropriate or Overreaction?

The previous edition of the DSM, DSM-IV, included the diagnosis of hypochondriasis, which pertained to people who worry excessively about their physical symptoms or about potential illnesses. This term was not included in DSM-5, partly because the DSM-5 team felt it had become pejorative (e.g., “acting like a hypochondriac”) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). As noted in this chapter, people previously diagnosed with hypochondriasis are now diagnosed either with somatic symptom disorder (in which the response to physical symptoms is greater than would be expected) or illness anxiety disorder (in which patients worry persistently about potentially having or developing a medical condition). Is this change warranted?

On one hand, it is not clear that the new categories make sense. If illness anxiety is so different from worries about actual symptoms, then why isn’t it grouped with anxiety disorders (Frances, 2013)? If the difference is about the presence of actual bodily symptoms, maybe instead of two separate categories, we might have two traits that each fall on a spectrum of intensity of physical symptoms and levels of anxiety.

On the other hand, the new, separate diagnoses are useful because they may lead more people to appropriate treatment; both disorders apply to people who are more likely to go, at least initially, to a medical doctor’s office rather than a mental health clinician’s office. And physicians may be more likely to use the new labels because they feel the new labels are less pejorative—at least for now.

CRITICAL THINKING Which of these three diagnoses—hypochondriasis, SSD, or illness anxiety disorder—do you think is most pejorative, and which do you think is least stigmatizing? Why? How would you explain each of these diagnoses to patients?

(James Foley, College of Wooster)

What Is Illness Anxiety Disorder?

Patients with illness anxiety disorder may or may not realize that their worries are excessive for the situation; when they do not, they are said to have poor insight into their condition. Consider a man who sees floating “spots” and does not believe his eye doctor when told that such floaters are normal and nothing to worry about. The man probably doesn’t think that the doctor is lying about the spots, but he may believe that the doctor didn’t do a thorough enough eye examination; he may think that the floaters indicate that he is going blind or that he has a tumor. His worries about this problem are distressing and preoccupying to the point that he functions less well at work—not because of the floaters but because of his frequent thoughts about the floaters.

People with this disorder may spend hours on the Internet, searching for illness-related information to reassure themselves, only to become more anxious or worried (Starcevic & Berle, 2013). To be diagnosed with this disorder, this kind of preoccupation with a perceived health problem must cause significant distress or impair the person’s functioning and must have continued for at least 6 months (see TABLE 8.12). Because illness anxiety disorder is a newly defined disorder and most people (75%) previously diagnosed with hypochondriasis would now be diagnosed with somatic symptom disorder, additional facts about illness anxiety disorder, such as prevalence and course, are not known at this time. However, two thirds of people with this disorder are estimated to have at least one other psychological disorder, commonly anxiety or depressive disorders, and the disorder typically begins in early to middle adulthood (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

Like people with SSD, those with illness anxiety disorder don’t understand that even healthy people sometimes have aches and pains and other bodily discomforts. Instead, like the woman in Case 8.6, they unrealistically believe that having “good health” implies not having any unpleasant bodily symptoms (Barsky, Coeytaux, et al., 1993).

CASE 8.6 • FROM THE INSIDE: Illness Anxiety Disorder

I attended graduate school, held jobs, was married, had children. But my existence was peppered with episodes of illness. When the going got tough, I’d get sick. Or just the opposite: when things seemed to be going well, I’d come down with a symptom, or at least what I interpreted as one. It might be stomach pain, dizziness, black and blue marks, swollen glands, an achy heel. Anything. Whatever the symptoms, I always interpreted it as a precursor of some crippling illness: leukemia, Lou Gehrig’s disease, scleroderma. I knew just enough about most diseases to cause trouble. Eventually I’d get past each episode, but it always took time—the cure a mysterious concoction of enough negative tests, a lessening of symptoms, some positive change in my life. And when the event was over, the realization that I was healthy and wasn’t going to die, at least not immediately, was like a high, a reprieve, a new lease on life. That is, until the next time.

(Cantor, 1996, pp. 9–10)

Illness Anxiety Disorder, Anxiety Disorders, and OCD: Shared Features

Illness anxiety disorder has many features in common with anxiety disorders. In fact, certain forms of illness anxiety disorder and anxiety disorders are so similar that some researchers have advocated moving illness anxiety disorder from the category of somatic symptom disorders to the category of anxiety disorders (Mayou et al., 2005). Illness anxiety disorder, phobias, and panic disorder are all characterized by high levels of fear and anxiety, as well as a faulty belief of harm or danger. However, with illness anxiety disorder and panic disorder, the perceived danger is from an internal event that is thought to be producing a bodily sensation, whereas with phobias, it is from an external object (such as a snake) or a situation (such as giving a speech; Fava, Mangelli, & Ruini, 2001). People with panic disorder, phobias, and illness anxiety disorder all may try to avoid certain stimuli or situations; with panic disorder and illness anxiety disorder, what is avoided may be an elevated heart rate (Hiller et al., 2002).

In addition, both patients with illness anxiety disorder and those with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) have obsessions and compulsions (Abramowitz & Braddock, 2006). In particular, patients with illness anxiety disorder obsess about possible illnesses or diseases they believe they might have. They may compulsively ask doctors, friends, or family members for reassurance or compulsively “check” their body for particular sensations. People with some forms of illness anxiety disorder spend hours compulsively consulting medical websites. It’s important to keep in mind that some medically related Internet chat rooms or websites can spread false or misleading information.

Understanding Illness Anxiety Disorder

Because illness anxiety disorder is a diagnosis new to DSM-5, most research related to this disorder studied people diagnosed with hypochondriasis. Hence we use the term hypochondriasis when discussing studies of people with that diagnosis, and the term illness anxiety disorder when discussing experiences and symptoms that clearly apply to the new disorder. Most research has examined psychological factors, and not enough is known about neurological and social factors to understand the feedback loops among the types of factors.

Neurological Factors

Some researchers have suggested that the neurotransmitter serotonin does not function properly in at least some cases (King, 1990). As we’ll see in the section on treatment, there is some indirect support for this hypothesis, based on the observation that SSRIs (which selectively affect serotonin reuptake) appear to improve the disorder. That is, the mere fact that SSRIs can improve the symptoms is evidence that the symptoms arise, at least in part, from disruption of the activity of serotonin. In addition, results from one twin study suggest that genetic differences contribute to hypochondriasis (Gillespie et al., 2000).

Psychological Factors: Catastrophic Thinking About the Body

People with hypochondriasis have specific biases in their reasoning: Not surprisingly, given their disorder, they both tend to seek evidence of health threats and also may fail to consider evidence that such threats are minimal or nonexistent (Salkovskis, 1996; Smeets et al., 2000). For instance, a man with illness anxiety disorder who notices a bruise on his leg might interpret it as evidence that he has leukemia rather than try to remember whether he recently bumped into something that could cause a black-and-blue mark.

In addition, people afflicted with illness anxiety disorder focus attention closely on unpleasant sensations. They commonly focus on the functioning of body parts (such as the stomach or the heart), minor physical problems (such as a sore throat), and ambiguous physical sensations (such as “aching veins”). Moreover, they interpret bodily sensations as abnormal, pathological, and symptomatic of disease (Barsky, 1992; Barsky et al., 2000). In fact, like patients with SSD, patients with hypochondriasis (and likely with illness anxiety disorder) may engage in catastrophic thinking about their physical sensations or fears of illness, just as the woman in Case 8.6 did when she interpreted physical sensations as signs of “crippling illness.”

As is the case with many anxiety disorders, people with illness anxiety disorder may engage in behaviors that temporarily reduce their anxiety. For example, they may repeatedly take their blood pressure, perform urine dipstick tests, feel body parts for cancerous lumps, or call their doctor about new symptoms. Such behaviors maintain their faulty beliefs and can, through negative reinforcement, sustain their anxiety in the long term.

Social Factors: Stress Response

As with other somatic symptom disorders, research has shown that stressful events can precipitate hypochondriasis (Fallon & Feinstein, 2001). In addition, such people are more likely than people without the disorder to report having experienced traumatic sexual contact, physical violence, or major familial upheaval (such as their parents’ divorce) (Barsky, Wool, et al., 1994). Moreover, through their attention and concern, relatives and friends may unintentionally reinforce patients’ symptoms.

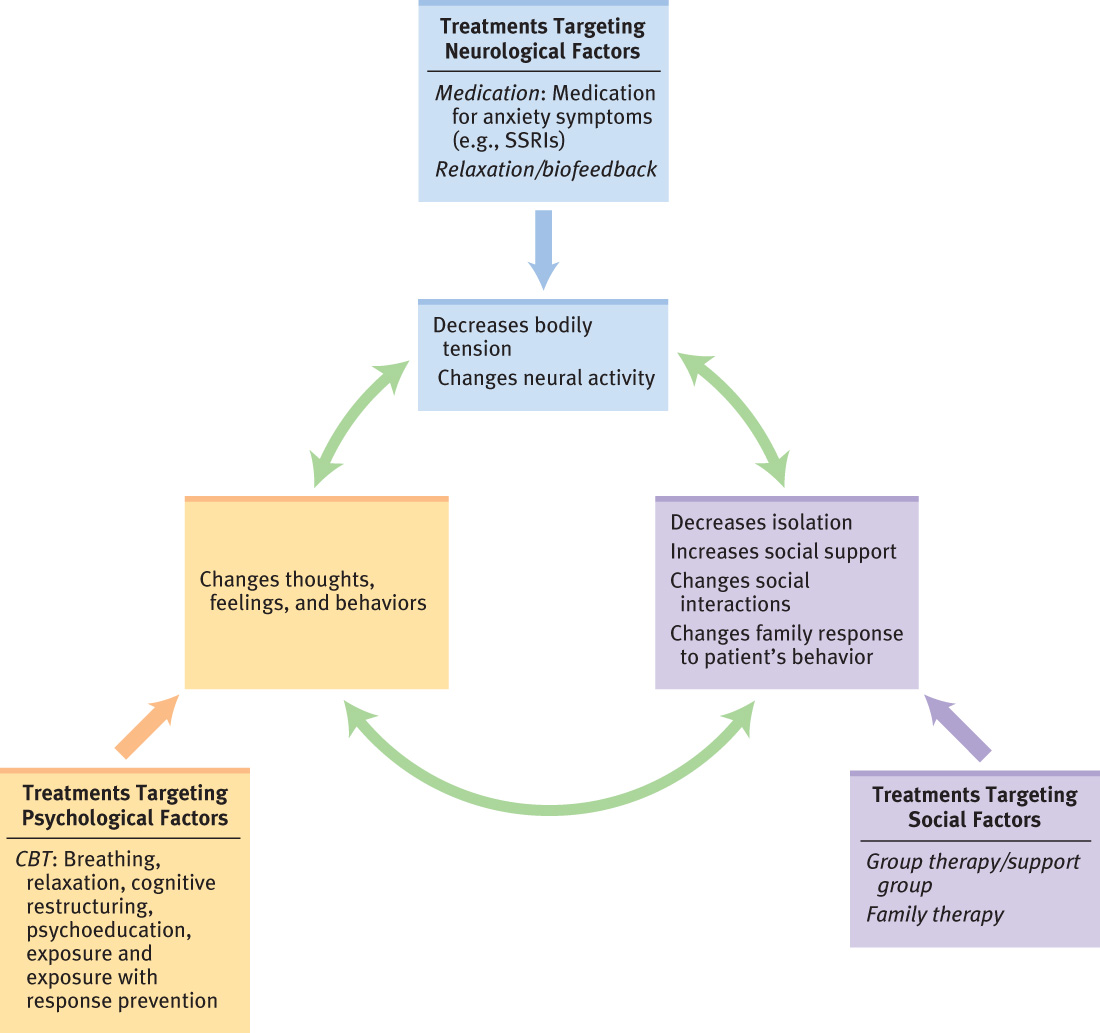

Treating Somatic Symptom Disorders

When treating any of the three somatic symptom disorders (SSD, conversion disorder, or illness anxiety disorder), clinicians target neurological, psychological, and social factors—individually or in combination. As we discuss below, cognitive-behavior therapy is generally the treatment of choice for somatic symptom disorders.

Targeting Neurological Factors

There has not been much rigorous research on neurologically-based treatments for somatic symptom disorders in general; the studies that have been reported have rarely included appropriate control groups, such as a placebo group or a wait-list control group to determine whether the disorder spontaneously improves with time. Some treatments target specific symptoms. For instance, medications, such as an SSRI, or St. John’s wort may be used to treat some anxiety-related symptoms of somatic symptom disorders. As with anxiety disorders, however, when the medication is stopped, the anxiety-related symptoms usually return. Other types of treatments, such as biofeedback, target muscle tension.

Were Anna O. to be treated by a mental health clinician today, she might receive medication. Anxiety or depression may have contributed to her symptoms, and if medication for these disorders did not alleviate her hallucinations, the clinician might recommend an antipsychotic medication (Martorano, 1984). Note that Anna O. was given medications frequently used at that time: morphine (typically given for pain relief) and chloral hydrate (a narcotic used to induce sleep). She became addicted to both of these substances, and after her “talking cure” with Breuer ended, she needed inpatient treatment to end her addiction.

Targeting Psychological Factors: Cognitive-Behavior Therapy

Research indicates that the treatment of choice for most somatic symptom disorders is cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT). As shown in TABLE 8.13, the cognitive and behavioral methods used to treat each of the disorders vary because each disorder has different symptoms. Cognitive methods focus on identifying and then modifying irrational thoughts and shifting attention away from the body and bodily symptoms (Gropalis et al., 2013). Behavioral methods focus on decreasing compulsive behaviors and avoidance.

| Disorder | Cognitive focus | Behavioral focus | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic symptom disorder (SSD) | Psychoeducation; cognitive restructuring to modify faulty or irrational beliefs about bodily sensations; teach patients not to amplify the sensations | Identify and then decrease avoidant behaviors, sensations, and activities that lead to physical or psychological discomfort or restriction of activitiesa; assertiveness training; relaxation to decrease physical tension | CBT is generally the most effective treatment for somatic symptom disorder.b |

| Conversion disorder | Psychoeducation; identify stressors or conflicts associated with the emergence of symptoms; develop alternative ways to resolve the conflict or cope with stressors (problem solving)c | Assertiveness training; to decrease symptoms, use paradoxical intention (suggest that the patient continue to have the symptom), as appropriated | Insight-oriented treatment is sometimes used to help patients with conversion disorder understand the meaning of the symptoms. Once the meaning is understood, the symptoms may improve spontaneously.e |

| Illness anxiety disorder | Identify and modify faulty or irrational beliefs about health worries and bodily sensations (cognitive restructuring); teach patients not to amplify these sensations; decrease catastrophic attributions about sensations and illness worries | Identify sensations and activities that lead to discomfort; identify avoidant behaviors and decrease avoidance; use exposure with response prevention for compulsive behaviors such as checking the body, seeking reassurance, or visiting doctors frequently | CBT is the most effective treatment for illness anxiety disorder.f Pilot studies have adapted interpersonal therapy to treat illness anxiety disorder, and initial results are promising.g |

|

aMayou & Farmer, 2002; O’Malley et al., 1999; bAllen et al., 2006; Bass et al., 2001; cMaldonado & Spiegel, 2001; dAtaoglu et al., 2003; eMaldonado & Spiegel, 2001; fBarsky & Ahern, 2004; Taylor et al., 2005; Wattar et al., 2005; gStuart & Noyes, 2005; Stuart et al., 2008. |

|||

Targeting Social Factors: Support and Family Education

Patients with any of the somatic symptom disorders can be helped, in part, merely by feeling that someone understands the pain and distress they feel (Looper & Kirmayer, 2002). For SSD and conversion disorder, the therapist strives to understand the context of the symptoms and of their emergence and the way the symptoms affect the patient’s interactions with others (Holder-Perkins & Wise, 2001); with these two disorders, treatment may focus on helping the patient communicate more assertively—which can help to relieve the social stressors that contribute to the disorders.

Treatment may also focus on the family—educating family members about the disorder and the ways they may have inadvertently contributed to or reinforced the patient’s symptoms. The therapist may teach family members how to reinforce positive change and to extinguish behavior related to the symptoms (Looper & Kirmayer, 2002; Maldonado & Spiegel, 2001). For instance, if the patient has SSD, family members may be asked not to inquire about the patient’s bodily symptoms. In addition, support groups may help patients feel less alone and isolated (Looper & Kirmayer, 2002).

Feedback Loops in Treating Somatic Symptom Disorders

ONLINE

CBT can provide new skills and new ways to interpret the sensations and modify the preoccupying thoughts, which in turn can decrease the bodily symptoms (neurological factor) and the attention paid to them (psychological factor). Similarly, although biofeedback and medication primarily target neurological factors, these techniques can in turn affect the type and quality of attention paid to bodily sensations and can change the meaning made of bodily sensations (psychological factors). In addition, the relationship with a therapist (social factor) can provide reassurance and support; as family members change how they respond to the patient’s symptoms (social factor), positive change can be enhanced. Figure 8.4 shows how successful treatment of somatic symptom disorders affects the different types of factors directly and through their feedback loops.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Now 57 years old, Mr. Andre left his native Haiti 5 years ago and moved to the United States. Unemployment rates in the United States were high at the time of his arrival, and Mr. Andre had a hard time finding a job; he felt that he was being discriminated against. His wife supported the family for 2 years by cleaning houses. After 2 years of looking, Mr. Andre did get a job. However, within 4 months of starting this job, he had a bout of the flu, and he continued to feel tired even after he recovered from it. He began to worry that he might be developing cancer. (His father had died of cancer.) He went to see his doctor and had a variety of tests that were all negative. Nonetheless, Mr. Andre thinks that the doctors may have “missed something” or not given him the right test. He worries about this, and frequent visits to the doctor mean that he must rearrange his work schedule or miss work. What factors should (and shouldn’t) clinicians take into account when evaluating Mr. Andre for some type of somatic symptom disorder? If they do think he has such a disorder, which one do you think it might be, and why? What treatment(s) should be recommended to Mr. Andre if you are correct? On what basis could some of the somatic symptom disorders be ruled out?