The American Promise: Printed Page 343

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 313

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 358

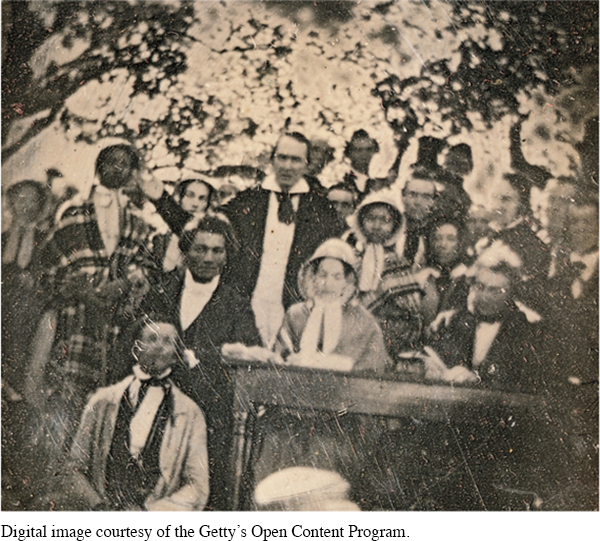

Abolitionists and the American Ideal

The American Promise: Printed Page 343

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 313

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 358

Page 343During the 1840s and 1850s, abolitionists continued to struggle to draw the nation’s attention to the plight of slaves and the need for emancipation. Former slaves Frederick Douglass, Henry Bibb, and Sojourner Truth lectured to reform audiences throughout the North about the cruelties of slavery. Abolitionists published newspapers, held conventions, and petitioned Congress, but they never attracted a mass following among white Americans. Many white Northerners became convinced that slavery was wrong, but they still believed that blacks were inferior. Many other white Northerners shared the common view of white Southerners that slavery was necessary and even desirable. The westward extension of the nation during the 1840s offered abolitionists an opportunity to link their unpopular ideal to a goal that many white Northerners found much more attractive—

Black leaders rose to prominence in the abolitionist movement during the 1840s and 1850s. African Americans had actively opposed slavery for decades, but a new generation of leaders came to the forefront in these years. Frederick Douglass, Henry Highland Garnet, William Wells Brown, Martin R. Delany, and others became impatient with white abolitionists’ appeals to the conscience of the white majority. In 1843, Garnet urged slaves to choose “Liberty or Death” and rise in insurrection against their masters, an idea that alienated almost all white people and had little influence among slaves. To express their own uncompromising ideas, black abolitionists founded their own newspapers and held their own antislavery conventions, although they still cooperated with sympathetic whites.

The commitment of black abolitionists to battling slavery grew out of their own experiences with white supremacy. The 250,000 free African Americans in the North and West constituted less than 2 percent of the total population in 1860. They confronted the humiliations of racial discrimination in nearly every arena of daily life. Only Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont—

The American Promise: Printed Page 343

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 313

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 358

Page 344Some cooperated with the efforts of the American Colonization Society to send freed slaves and other black Americans to Liberia in West Africa. Others sought to move to Canada, Haiti, or elsewhere. As one African American from Michigan wrote, “It is impracticable, not to say impossible, for the whites and blacks to live together, and upon terms of social and civil equality, under the same government.” Most black American leaders refused to embrace emigration and worked against racial prejudice in their own communities, organizing campaigns against segregation, particularly in transportation and education. Their most notable success came in 1855 when Massachusetts integrated its public schools. Elsewhere, white supremacy continued unabated.

Outside the public spotlight, free African Americans in the North and West contributed to the antislavery cause by quietly aiding fugitive slaves. Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery in Maryland in 1849 and repeatedly risked her freedom and her life to return to the South to escort slaves to freedom. When the opportunity arose, free blacks in the North provided fugitive slaves with food, a safe place to rest, and a helping hand. An outgrowth of the antislavery sentiment and opposition to white supremacy that unified nearly all African Americans in the North, this underground railroad ran mainly through black neighborhoods, black churches, and black homes.

REVIEW Why were women especially prominent in many nineteenth-