The American Promise: Printed Page 391

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 358

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 410

“Bleeding Kansas”

The American Promise: Printed Page 391

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 358

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 410

Page 391Three days after the House of Representatives approved the Kansas-

Emigrant aid societies sprang up to promote settlement from free states or slave states. Missourians, already bordered on the east by the free state of Illinois and on the north by the free state of Iowa, especially thought it important to secure Kansas for slavery. Thousands of rough frontiersmen, egged on by Missouri senator David Rice Atchison, invaded Kansas. “There are eleven hundred coming over from Platte County to vote,” Atchison reported, “and if that ain’t enough we can send five thousand—

The American Promise: Printed Page 391

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 358

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 410

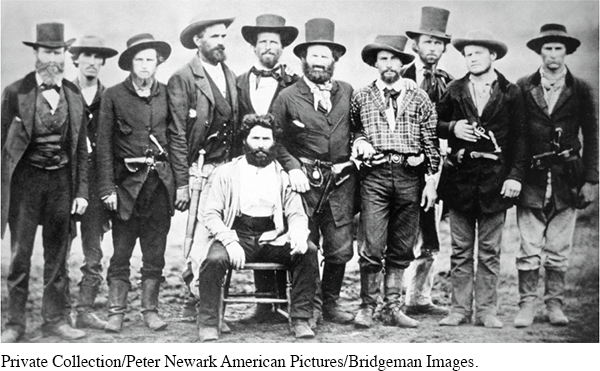

Page 393Fighting broke out on the morning of May 21, 1856, when several hundred proslavery men raided the town of Lawrence, the center of free-

Just as “Bleeding Kansas” gave the fledgling Republican Party fresh ammunition for its battle against the Slave Power, so too did an event that occurred in the national capital. In May 1856, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts delivered a speech titled “The Crime against Kansas,” which included a scalding personal attack on South Carolina senator Andrew P. Butler. Sumner described Butler as a “Don Quixote” who had taken as his mistress “the harlot, slavery.”

The American Promise: Printed Page 391

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 358

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 410

Page 394Preston Brooks, a young South Carolina member of the House and a kinsman of Butler’s, felt compelled to defend the honor of his aged relative. On May 22, Brooks entered the Senate, where he found Sumner working at his desk. He beat Sumner over the head with his cane until Sumner lay bleeding and unconscious on the floor. Brooks resigned his seat in the House, only to be promptly reelected. In the North, the southern hero became an archvillain. Like “Bleeding Kansas,” “Bleeding Sumner” provided the Republican Party with a potent symbol of the South’s “twisted and violent civilization.”