The American Promise: Printed Page 513

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 469

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 533

Gender, Race, and Politics

Gender—

Women were not alone in their limited access to the public sphere. Blacks continued to face discrimination well after Reconstruction, especially in the New South. Segregation, commonly practiced through Jim Crow laws (see “Progressivism for White Men Only” in chapter 21), prevented ex-

The American Promise: Printed Page 513

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 469

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 533

Page 514Amid the turmoil of the post-

The notion that black men threatened white southern womanhood reached its most vicious form in the practice of lynching—

The American Promise: Printed Page 513

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 469

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 533

Page 515

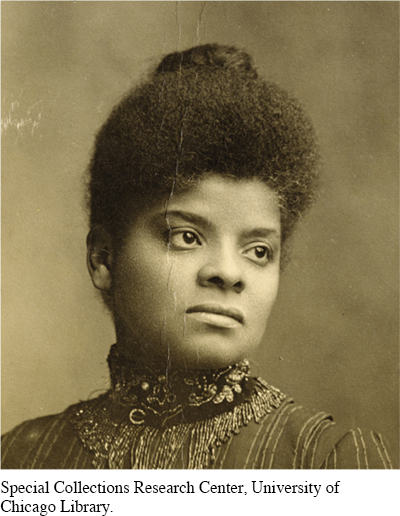

Wells articulated lynching as a problem of gender as well as race. She insisted that the myth of black attacks on white southern women masked the reality that mob violence had more to do with economics and the shifting social structure of the South than with rape. She demonstrated in a sophisticated way how the southern patriarchal system, having lost its control over blacks with the end of slavery, used its control over white women to circumscribe the liberty of black men.

Wells’s outspoken stance immediately resulted in reprisal. While she was traveling in the North, vandals ransacked her office in Tennessee and destroyed her printing equipment. Yet the warning that she would be killed on sight if she ever returned to Memphis only stiffened her resolve. As she wrote in her autobiography, Crusade for Justice (1928), “Having lost my paper, had a price put on my life and been made an exile . . . , I felt that I owed it to myself and to my race to tell the whole truth now that I was where I could do so freely.”

Lynching did not end during Wells’s lifetime, but her forceful voice brought the issue to national and international prominence. At Wells’s funeral in 1931, black leader W. E. B. Du Bois eulogized Wells as the woman who “began the awakening of the conscience of the nation.” Wells’s determined campaign against lynching provided just one example of women’s political activism during the Gilded Age. The suffrage and temperance movements, along with the growing popularity of women’s clubs, dramatized how women refused to be relegated to a separate sphere that kept them out of politics.