The American Promise: Printed Page 531

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 490

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 555

Racism and the Cry for Immigration Restriction

Ethnic diversity and racism played a role in dividing skilled workers (those with a craft or specialized ability) from the globe-

The Irish worker’s resentment brings into focus the impact racism had on America’s immigrant laborers. Throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, members of the educated elite as well as the uneducated viewed ethnic and even religious differences as racial characteristics, referring to the Polish or the Jewish “race.” Americans judged immigrants of southern and eastern European “races” as inferior. Each wave of newcomers was deemed somehow inferior to the established residents. The Irish who criticized the Italians so harshly had themselves been stigmatized as a lesser “race” a generation earlier.

The American Promise: Printed Page 531

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 490

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 555

Page 533Immigrants not only brought their own religious and racial prejudices to the United States but also absorbed the popular prejudices of American culture. Social Darwinism, with its strongly racist overtones, decreed that whites stood at the top of the evolutionary ladder. But who was “white”? Skin color supposedly served as a marker for the “new” immigrants—

The American Promise: Printed Page 531

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 490

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 555

Page 534For African Americans, the cities of the North promised not just economic opportunity but an escape from institutionalized segregation and persecution. Throughout the South, Jim Crow laws—

On the West Coast, Asian immigrants became scapegoats of the changing economy. Hard times in the 1870s made them a target for disgruntled workers, who dismissed them as “coolie” labor. Contract laborers recruited by employers, or later by prosperous members of their own race or ethnicity, represented the antithesis of free labor to the workers who competed with them. In the West, the issue became racialized, and while the Chinese were by no means the only contract laborers, the Sinophobia that produced the scapegoat of the “coolie” permeated the labor movement. Prohibited from owning land, the Chinese migrated to the cities. In 1870, San Francisco housed a Chinese population estimated at 12,022, and it continued to grow until passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 (see “The Diverse Peoples of the West” in chapter 17). For the first time in the nation’s history, U.S. law excluded an immigrant group on the basis of race.

Some Chinese managed to come to America using a loophole in the exclusion law that allowed relatives to join their families. Meanwhile the number of Japanese immigrants rapidly grew until pressure to keep out all Asians led in 1910 to the creation of an immigration station at Angel Island in San Francisco Bay, where immigrants were quarantined until judged fit to enter the United States.

On the East Coast, the volume of immigration from Europe in the last two decades of the century proved unprecedented. In 1888 alone, more than half a million Europeans landed in America, 75 percent of them in New York City. The Statue of Liberty, erected in 1886 as a gift from the people of France, stood sentinel in the harbor.

A young Jewish woman named Emma Lazarus penned the verse inscribed on Lady Liberty’s base:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

Lazarus’s poem stood as both a promise and a warning. With increasing immigration, some Americans soon would question whether the country really wanted the “huddled masses” or the “wretched refuse” of the world.

The tide of immigrants to New York City soon swamped the immigration office in lower Manhattan. After the federal government took over immigration in 1890, it built a facility on Ellis Island, in New York harbor, which opened in 1892. After fire gutted the wooden building, a new brick edifice replaced it in 1900. Able to process 5,000 immigrants a day, it was already inadequate by the time it opened. Its overcrowded halls became the gateway to the United States for millions.

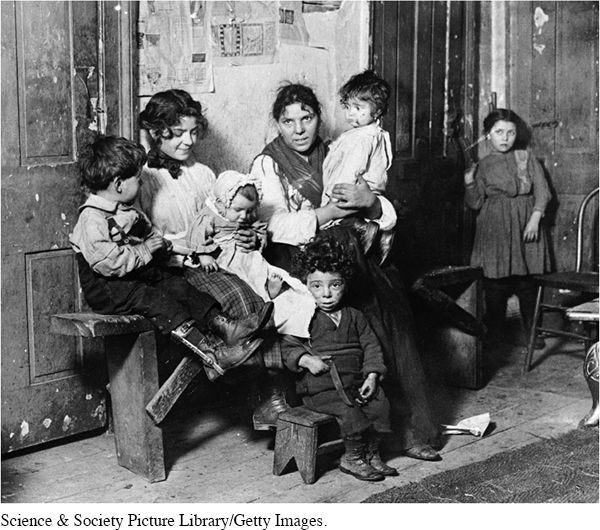

To many Americans the new southern and eastern European immigrants appeared backward, uneducated, and outlandish in appearance—