The American Promise: Printed Page 757

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 685

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 784

Reconverting to a Peacetime Economy

Despite scarcities and deprivations, World War II had brought most Americans a higher standard of living than ever before. Economic experts as well as ordinary citizens worried about sustaining that standard and providing jobs for millions of returning soldiers. To that end, Truman asked Congress for a twenty-

Congress approved just one of Truman’s key proposals—

The American Promise: Printed Page 757

The American Promise, Value Edition: Printed Page 685

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 784

Page 758Inflation, not unemployment, turned out to be the biggest problem. Consumers had $30 billion in wartime savings to spend, but shortages of meat, automobiles, housing, and other items persisted, thereby driving up prices. With a basket of groceries to dramatize rising costs, Helen Gahagan Douglas urged Congress to maintain price and rent controls. Those efforts, however, fell to pressures from business groups and others determined to trim government powers.

Labor relations were another thorn in Truman’s side. Organized labor emerged from the war with its 14.5 million members making up 35 percent of the nonagricultural workforce. Yet union members feared the erosion of wartime gains and turned to the weapon they had surrendered during the war. Five million workers went out on strike in 1946, affecting nearly every major industry. Shortly before voting to strike, a former Marine and his coworkers calculated that an executive had spent more on a party than they would earn in a whole year at the steel mill. “That sort of stuff made us realize, hell we had to bite the bullet. . . . The bosses sure didn’t give a damn for us.” Although most Americans approved of unions in principle, they became fed up with strikes and blamed unions for shortages and rising prices. When the strikes subsided, workers had won wage increases of about 20 percent, but the loss of overtime pay and rising prices left their purchasing power only slightly higher than in 1942.

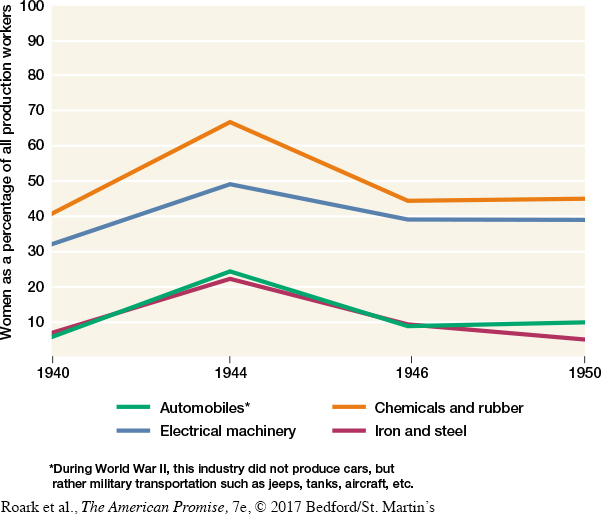

Women workers fared even worse. Polls indicated that 68 to 85 percent wanted to keep their wartime jobs, but most who remained in the workforce had to settle for relatively low-

By 1947, the economy had stabilized, avoiding the postwar depression that so many had feared. Wartime profits enabled businesses to expand. Consumers could now spend their wartime savings on items that had lain beyond their reach during the depression and war. Defense spending and foreign aid that enabled war-

Another economic boost came from the only large welfare measure passed after the New Deal. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (GI Bill), enacted in 1944, offered 16 million veterans job training and education; unemployment compensation until they found jobs; and low-

Yet the impact of the GI Bill was uneven. As wives and daughters of veterans, women benefited indirectly from the GI subsidies, but few women qualified for the employment and educational preferences available to some 15 million men. Moreover, GI programs were administered at the state and local levels, which resulted in routine racial and ethnic discrimination, especially in the South. Southern universities remained segregated, and historically black colleges could not accommodate all who wanted to attend. Black veterans were shuttled into menial labor. One decorated veteran reported “My color bars me from most decent jobs, and if, instead of accepting menial work, I collect my $20 a week readjustment allowance, I am classified as a ‘lazy nigger.’” Thousands of black veterans did benefit, but the GI Bill did not help all ex-