The American Promise: Printed Page 764

EXPERIENCING THE AMERICAN PROMISE

The American Promise: Printed Page 764

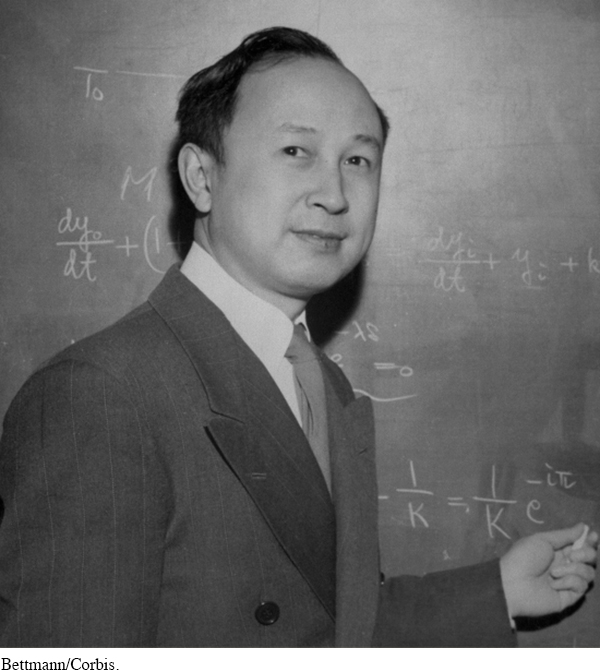

Page 764An Immigrant Scientist Encounters the Anti-

Qian Xuesen (Tsien Hsue-

At Caltech, Qian joined a group of scientists working on questions about flight and contributed to the development of theoretical aerodynamics and jet propulsion, which eventually provided a foundation for America’s space program. School officials were so impressed with Qian’s work that they helped him get a visa extension, and in 1942 the government gave him security clearance so that he could work on secret military projects. Qian served on the air force’s Scientific Advisory Board, and after World War II he went on a U.S. mission to interview Nazi scientists in Germany. He spent a year on the faculty at MIT and then traveled home to China amid the turmoil of a civil war between the Communists, led by Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-

In 1949, he returned to Caltech to direct the Jet Propulsion Center, teach, and continue his lifelong passion for scientific research. With satisfying work and a close circle of colleagues whom he entertained with classical music and elaborate dinners, Qian seemed to have all he could want. He applied for U.S. citizenship, but one year later, after the Communists had taken control of China, the U.S. government revoked Qian’s security clearance. The FBI interrogated him about a group he had socialized with in the 1930s, which the FBI said was a cell of the Communist Party. Qian denied any participation in Communist activities, but the proud, angry, and humiliated scientist concluded that, given the “cloud of suspicion . . . the only gentlemanly thing left to do is to depart.” The promise of a brilliant career shattered, he resisted Caltech officials who begged him to remain; instead, he readied a shipment of his belongings to send on to China. The government seized the shipment and accused Qian of taking secret documents. Although the claim was later refuted, the Immigration and Naturalization Service arrested him. He was released after two weeks, but for the next five years the government refused to let him go, kept him and his family under constant surveillance, and barred his research. Although Caltech administrators worked furiously to clear his name, some of his associates began to avoid him, fearing that they, too, would be caught up in the hunt for Communists. Finally, in 1955, he was deported as part of a prisoner of war exchange following the Korean War.

Qian disembarked in China with his wife and two children to a hero’s reception and a career that would eventually earn him the title of “father of Chinese rocketry.” Denied the full use of his talents by the United States, he organized and led China’s rocketry program, developing its ballistic missiles and satellites. Like anyone who hoped to have a successful career in China, he became a trusted Communist Party official. Though the extremely private scientist said little about his experiences in the United States, he refused to return in 1979 to accept Caltech’s Distinguished Alumni Award. Qian had lost faith in the U.S. government but maintained affection for the American people and sent both his children to study at American universities. He died in China in 2009 at the age of ninety-

Questions linger about Qian’s associations and intentions in the United States. A 1999 congressional report maintained that he had been a spy, but his supporters claimed that the report lacked evidence. Every one of his Caltech colleagues vouched for his integrity, and some went to great lengths to defend him against government charges. Dan A. Kimball, who was secretary of the navy in the early 1950s, later said that Qian’s deportation “was the stupidest thing this country ever did. He was no more a Communist than I was—

Questions for Analysis

Consider the Context: How did the timing of events in Qian’s case correlate with domestic and international developments related to the Cold War and McCarthyism? How were other people and ideas silenced during the Red scare?

Analyze the Evidence: What does Qian’s case reveal about the power of individual agency? Could he have done anything differently to avoid the surveillance and subsequent deportation?

Ask Historical Questions: What caused Qian’s status to change from that of trusted government adviser to that of suspected subversive?