The American Promise: Printed Page 754

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 780

MAKING HISTORICAL ARGUMENTS

The American Promise: Printed Page 754

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 780

Page 754Why Did the United States Launch the European Recovery Program?

When Secretary of State George Marshall proposed a program of massive economic aid to Europe in June 1947, the United States was still recovering from World War II, the national debt had skyrocketed, and most Americans ranked foreign events low among their concerns. The Truman administration insisted that $17 billion was needed over the next four years and asked specifically for $6.8 billion for the first 15 months, a staggering amount when the total annual federal budget was around $40 billion. The $13 billion that was ultimately spent amounted to more than $100 billion in current dollars. So why did the administration believe it was necessary to launch such an enormous program, and why did Congress consent?

The objective conditions in Europe were plain for anyone to see. World War II had left behind utter devastation. Thirty percent of Britain’s housing stock lay in rubble, and three-

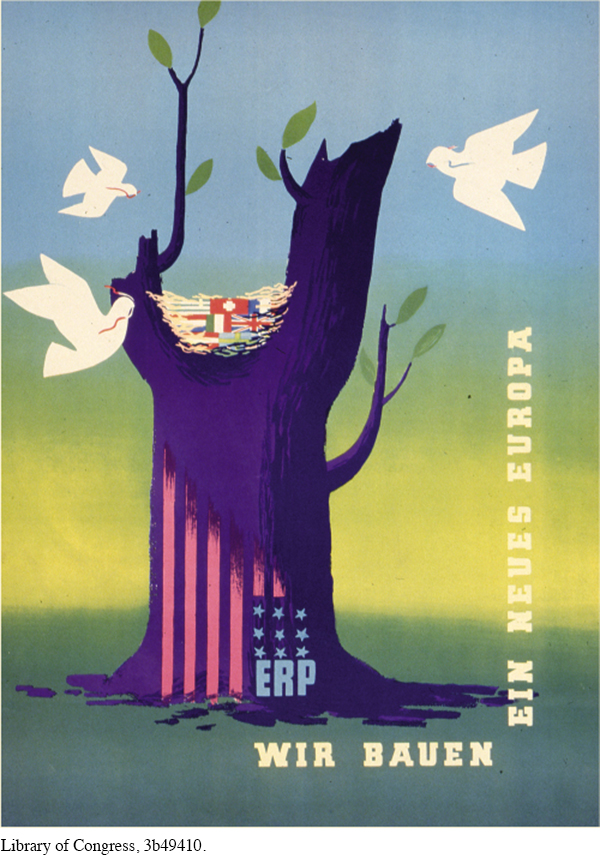

When Marshall proposed what came to be called the European Recovery Program (ERP), he declared, “Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos.” Indeed, the U.S. government had already sent millions of dollars of aid and huge loans to individual countries, and the American people sent some $2 billion of private aid in the six years following World War II. British foreign secretary Ernest Bevin spoke of the Marshall Plan as “generosity beyond my belief.”

But motives beyond humanitarianism were also at work. With the Soviet Union in control of Eastern Europe, U.S. policymakers feared the spread of communism to Western nations. In most of Europe, Communist parties enjoyed popular support, in part because Communists had led the resistance to Nazism. After the war, they were elected to coalition governments in several Western countries, including Italy, where a Communist coalition had won 40 percent of the vote, and France. U.S. leaders feared that persistent economic desperation could send Western European countries into the arms of the Soviets without a shot being fired.

If U.S. policy leaders were alarmed by the security threat posed by a Soviet-

Finally, the ERP helped to solve the problem of how to promote German reindustrialization, deemed necessary for the recovery of the rest of Western Europe, while also containing Germany’s ability to wage war. To this end, the United States required nations receiving aid to take the initiative, cooperate with one another, and lower trade restrictions among themselves. Encouraged by Marshall Plan aid, European leaders knit their countries together, eventually leading to the creation of the European Union in 1993.

The multitude of interests that lay behind the Marshall Plan proposal gave the Truman administration a broad platform on which to appeal for congressional support. It launched a full-

The American Promise: Printed Page 754

The American Promise: A Concise History: Printed Page 780

Page 755The Soviet Union made its own contributions to the enactment of the Marshall Plan. Not wanting to be judged responsible for the division of Europe, U.S. officials had extended the invitation to develop a recovery plan to every European nation. Foreign ministers from the Soviet Union, Britain, and France met to discuss a response, but Stalin balked at sharing economic information with other participants, and he wanted German industry used for reparations rather than for European recovery. The Soviet representative walked out of the meeting, and Stalin ordered the Eastern European satellites not to participate. Consequently, no U.S. aid would be going to Communist countries. Further solidifying public and congressional support for the Marshall Plan, the iron curtain moved westward in February 1948, when Communists in Czechoslovakia staged a coup and took over the government.

In the end, security interests carried the day. Senator Arthur Vandenberg, a leading Republican spokesman on foreign policy and an advocate for the Marshall Plan opened the debate on the ERP bill with the warning, “The exposed frontiers of hazard move almost hourly to the west.” Other members of Congress echoed their support for the Marshall Plan in terms that emphasized the Soviet threat, such as Oklahoma senator Elmer Thomas's argument that European aid would “enable the free countries of Europe to prepare themselves to resist the aggression of Russia over their territories.” A CIA report asserted in April 1947 that “the greatest danger to the security of the United States is the possibility of economic collapse in western Europe and the consequent accession to power of Communist elements.” Created to serve strategic interests, the Marshall Plan simultaneously helped the U.S. economy and highlighted values of generosity and humanitarianism.

Questions for Analysis

Summarize the Argument: What does the author conclude were the U.S. government’s primary motivations for launching the ERP?

Analyze the Evidence: What specific risks did the U.S. government hope to avoid by implementing the ERP? What conditions enabled the ERP to gain the support of the Republican-

Consider the Context: How did external events that occurred during the period between Marshall’s proposal for European aid in June 1947 and its enactment into law in April 1948 influence the passage of the ERP? What specific events were significant in the passage of the ERP?