Business and Politics in the Gilded Age, 1865–1900

Printed Page 476 Chapter Chronology

Business and Politics in the Gilded Age, 1865-1900

QUICK START

Quickly learn what is important in this chapter by doing the following:

- READ the Chapter Outline to see how the chapter is organized.

- SKIM the Chronology to see what will be covered.

When you are ready, download the Guided Reading Exercise, then read the chapter and the Essential Questions for each section and complete the Guided Reading Exercise as you go. Then use LearningCurve and the Chapter Review to check what you know.

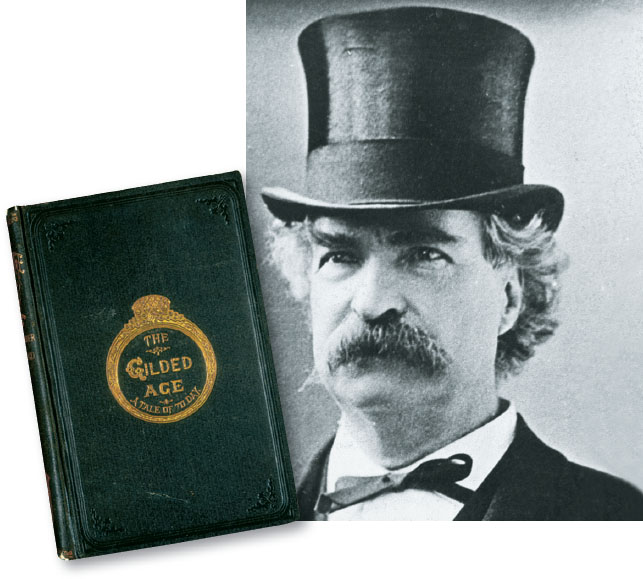

One night over dinner, Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner teased their wives about the sentimental novels they read. When the two women challenged them to write something better, they set to work. Warner supplied the melodrama, while Twain "hurled in the facts." The result was a runaway best seller, a savage satire of the "get-rich-quick" era that would forever carry the book's title, The Gilded Age (1873).

Twain left no one unscathed in the novel — political hacks, Washington lobbyists, Wall Street financiers, small-town boosters, and the "great putty-hearted public." Underneath the glitter of the Gilded Age lurked vulgarity, crass materialism, and political corruption. Twain witnessed firsthand the crooked administration of Ulysses S. Grant. In his satire, Congress is for sale to the highest bidder:

Why the matter is simple enough. A Congressional appropriation costs money. ...A majority of the House Committee, say $10,000 apiece — $40,000; a majority of the Senate Committee, the same each — say $40,000; a little extra to one or two chairmen of one or two such committees, say $10,000 each — $20,000; and there's $100,000 of the money gone, to begin with. Then, seven male lobbyists, at $3,000 each — $21,000; one female lobbyist, $3,000; a high moral Congressman or Senator here and there — the high moral ones cost more, because they give tone to a measure — say ten of these at $3,000 each, is $30,000; then a lot of small fry country members who won't vote for anything whatever without pay — say twenty at $500 apiece, is $10,000 altogether; lot of jimcracks for Congressmen's wives and children ...well, those things cost in a lump, say $10,000 ...and then comes your printed documents. ...[W]ell, never mind the details, the total in clean numbers foots up $118,254.42 thus far!

The Gilded Age seemed to tarnish all who touched it. No one knew that better than Twain, who, even as he attacked it as an "era of incredible rottenness," fell prey to its enticements. Born Samuel Langhorne Clemens, he grew up in a rough Mississippi River town, where he became a riverboat pilot. Taking the pen name Mark Twain, he wrote and played to packed houses as an itinerant humorist. But his work was judged too vulgar for the genteel tastes of the time. Boston banned his masterpiece, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, when it appeared in 1884. Huck Finn's creator eventually stormed the citadels of polite society and hobnobbed with the wealthy. Succumbing to the money fever of his age, he plunged into a scheme in the hope of making millions. By the 1890s, he faced bankruptcy. Twain's tale was common in an age when the promise of wealth led as many to ruin as to riches. Wall Street panics in 1873 and 1893 periodically plunged the country into depression.

The rise of industrialism and the corrupt interplay of business and politics strike the key themes in the Gilded Age. The growth of old industries and the creation of new ones, the surge in new technologies like electricity and inventions like the telephone and telegraph, along with the rise of big business, signaled the coming of age of industrial capitalism. Economic issues increasingly shaped party politics. The social philosophy of the age, social Darwinism, with its insistence on the "survival of the fittest," supported the power of the wealthy, while the poor and middle classes championed currency reform to ease debt and civil service to end corruption. As always, race, class, and gender influenced politics and policy.

Perhaps nowhere were the hopes and fears that industrialism inspired more evident than in the public's attitude toward the business moguls of the day. Men like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller sparked the popular imagination as the heroes and villains in the high drama of industrialization. And as concern grew over the power of big business and the growing chasm between rich and poor, many Americans, women as well as men, looked to the government for solutions.