TOO MUCH OF A GOOD THING

In normal circumstances, dopamine’s main job is to convey information related to elation and pain. The joy we get from a meal, a promotion, a winning poker hand, or sex–or anything that gives us pleasure–is conveyed in part by dopamine. Drugs of abuse stimulate dopamine production, which is why they can become so addictive.

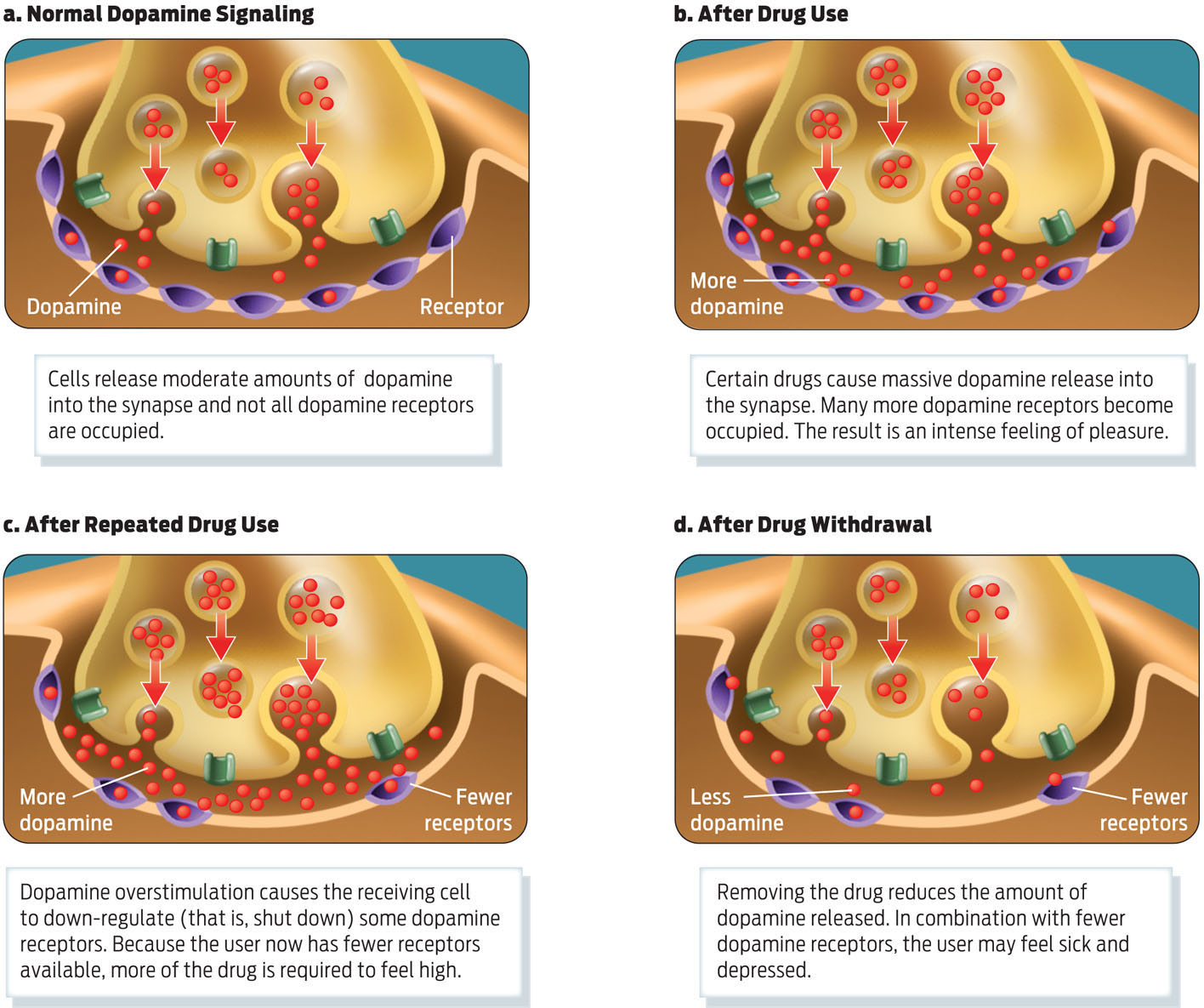

But these drugs cause such a high that over time they can alter the dopamine signaling system so that the pleasures of everyday life become meaningless compared to the pleasure of the drug. Normally the brain produces dopamine at a relatively constant rate, and dopamine occupies only a portion of dopamine receptors at any given time. But when a person smokes, snorts cocaine, or takes heroin, for example, dopamine levels in the synaptic cleft increase dramatically. With so much dopamine available, practically all of the brain’s dopamine receptors become activated simultaneously.

The immediate effect is euphoria. But there is a downside. Because so much dopamine is produced, the brain becomes overwhelmed and tries to dampen the drug’s effect by switching off some of its dopamine receptors (yet another example of homeostasis; see Chapter 25). When the drug wears off, fewer receptors are functioning–bringing down mood. Shutting down receptors that would otherwise be available to receive information is called down-regulation.

The low can be so low that normal pleasures such as eating or socializing become dull and listless affairs. The user’s mood may now be even lower than it was before taking the drug. As dopamine receptors shut down, ever-larger quantities of the drug are required to produce a high–and the high may never be as high as the user experienced the first time.

As dopamine receptors shut down, ever-larger quantities of the drug are required to produce a high–and the high may never be as high as the user experienced the first time.

As they come down from a high, addicts will likely feel even more unhappy and depressed as the dopamine response system is dampened. Eventually, many addicts need to take drugs simply to feel normal. Without drugs, they suffer the physical symptoms of withdrawal, which may include depression, anxiety, and intense cravings–for a dopamine fix. The specific symptoms and their intensity vary depending on the drug (INFOGRAPHIC 29.7).

Addictive drugs increase dopamine release, causing initial feelings of pleasure. Continued use of the drug alters dopamine signaling, requiring more drug to achieve the same high. Attempts to quit can be difficult because of symptoms of withdrawal, the result of diminished dopamine signaling.

A down-regulated dopamine system isn’t the only structural brain change that scientists have observed in drug addicts. Researchers have also shown that drugs such as cocaine can change the shape of neurons in specific parts of the brain and consequently may impair their ability to transmit signals. Brain-imaging studies have also shown that addicts consistently have lower than normal levels of blood flow in the frontal regions of the cerebrum, a region involved in decision making, during withdrawal from cocaine, and higher than normal levels while they are on the drug. In a variety of tests, drug addicts seem to make poorer decisions, with detrimental consequences.

Tobacco, for example, is responsible in some way for one out of every five deaths in the United States.

Even more troubling, adolescents who take drugs may be preventing their brains from developing normally. A 2004 study by researchers at University of California, Los Angeles, and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) that imaged the brains of 13 children and young people age 4 to 21 over 10 years showed that that some parts of the brain, such as the prefrontal cortex, are not fully developed until the mid-twenties or so. Taking drugs at an early age may hinder normal development of this region.

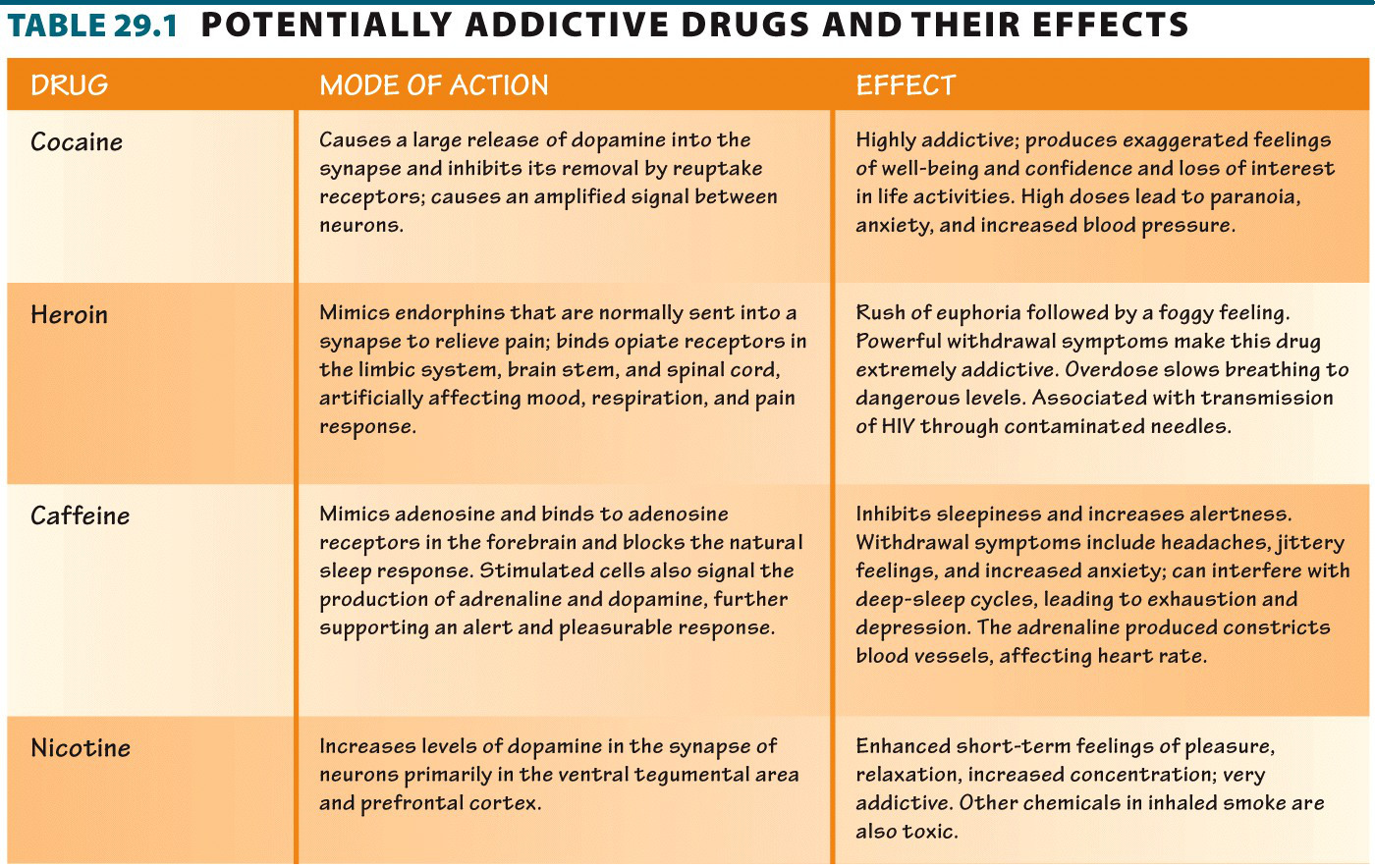

And that’s not the end of the story. There are several other neurotransmitters, in addition to dopamine, involved in addiction, says Joe Frascella, director of the division of Clinical Neuroscience and Behavioral Research at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and scientists are just starting to study how drugs of abuse affect them. While scientists have shown that almost every drug of abuse affects the dopamine system in varying degrees, Frascella says, “It’s certainly more complex than just dopamine.” Scientists have only just scratched the surface when it comes to learning exactly how long-term drug use affects the brain (TABLE 29.1) .