HORMONES AND PREGNANCY

Suleman’s doctor told the press that he agreed to give Suleman fertility treatments because she had been trying to become pregnant for several years without success. She had her first round of IVF in 2000, using sperm donated by a friend. Her doctor explained to her that the procedure would begin with a round of hormones to stimulate her ovaries so that her eggs could be harvested. This hormone treatment, he explained, would mimic what happens naturally in a woman’s body to trigger her reproductive cycle.

Hormones are responsible for regulating the production of gametes, both sperm and egg. In females, estrogen and progesterone are the key reproductive hormones that support egg maturation. In males, testosterone is the primary hormone that stimulates sperm to develop.

As we saw in Chapter 25, hormones are produced by endocrine glands, which secrete hormones into the circulation. These hormones then travel through the bloodstream to reach their target cells. Hormones interact with their target cells by binding to specific receptors on the target cells, influencing a range of physiological processes.

HYPOTHALAMUS A master control region in the brain that regulates a variety of physiological functions, including hunger, thirst, temperature regulation, and reproduction.

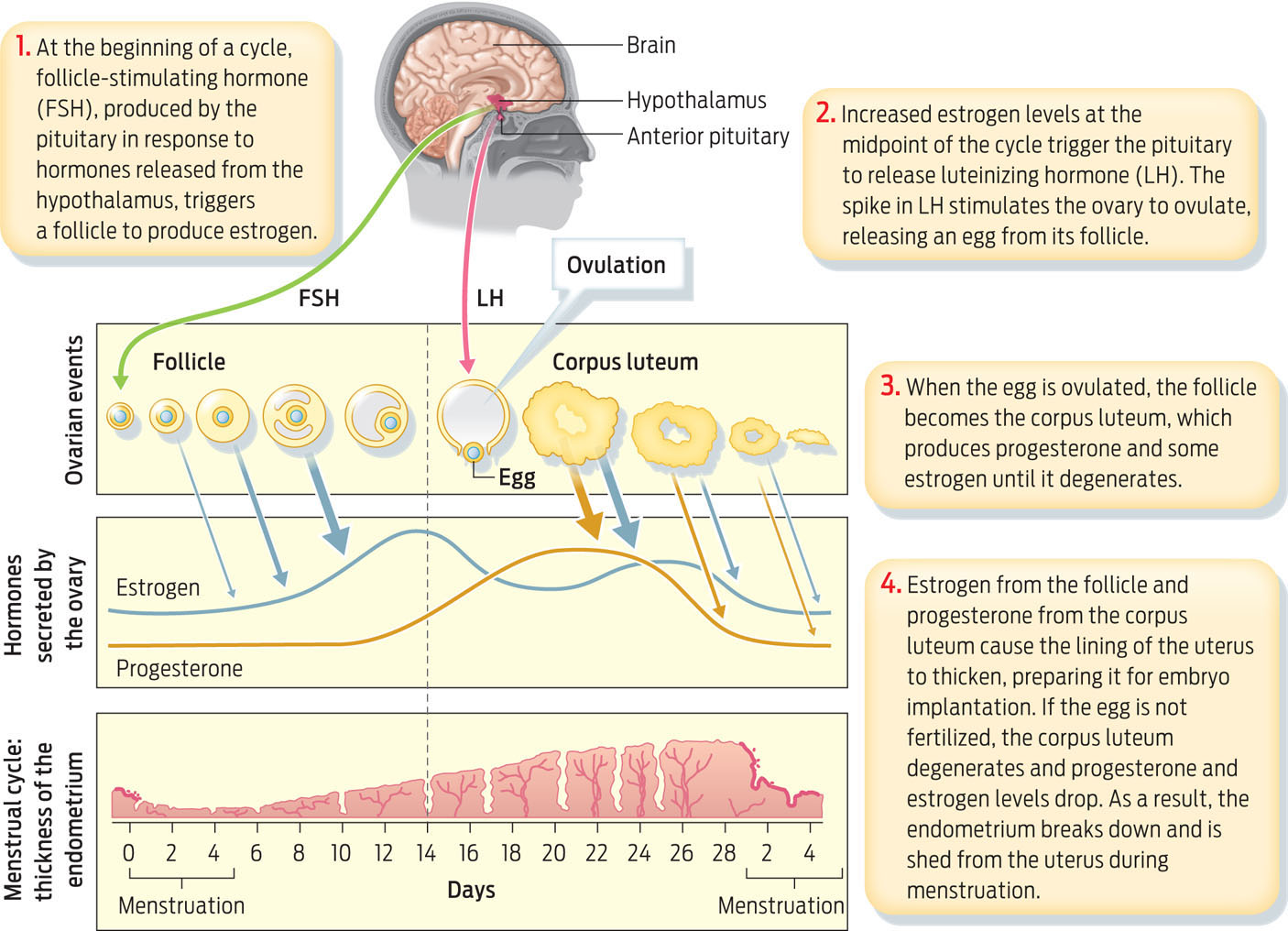

In females, estrogen and progesterone drive the menstrual cycle, a reproductive cycle that repeats roughly once every 28 days after the onset of puberty. During each cycle, estrogen and progesterone levels rise and fall, triggering the ovaries to release an egg and prepare a woman’s uterus for pregnancy should an egg be fertilized.

ANTERIOR PITUITARY The gland in the brain that secretes luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

The brain’s hypothalamus controls levels of estrogen and progesterone in the body and thus is the ultimate regulator of fertility. The hypothalamus works closely with another endocrine gland called the anterior pituitary, which sits just below the hypothalamus in the brain. The hypothalamus secretes hormones that act on the anterior pituitary, causing it to produce two hormones of its own. These hormones, called follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, travel through the bloodstream and directly stimulate the ovaries.

FOLLICLE-STIMULATING HORMONE (FSH) A hormone secreted by the anterior pituitary. In females, FSH triggers eggs to mature at the start of each monthly cycle.

FOLLICLE The part of the ovary where eggs mature.

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) acts on structures in the ovaries called follicles, each of which contains an immature egg. FSH signals follicles in the ovary to enlarge and to produce estrogen. Estrogen has several effects, one of which is to cause the endometrium to start to thicken. Estrogen also stimulates eggs within the ovaries to mature.

LUTEINIZING HORMONE (LH) A hormone secreted by the anterior pituitary. In females, a surge of LH triggers ovulation.

OVULATION The release of an egg from an ovary into the oviduct.

In most women, estrogen levels rise between 10 and 14 days after menstrual bleeding begins (considered the start of the menstrual cycle). This rise in estrogen triggers the brain to release a large amount of luteinizing hormone (LH). In turn, this LH surge triggers ovulation—the release of an egg from a follicle into the oviduct. After the egg has been ovulated, the remaining follicle becomes a structure called the corpus luteum, which secretes progesterone. One of the most important roles of progesterone is to promote the continued thickening of endometrium. The thickened endometrium contains blood vessels and nutrients and is prepared to receive an embryo if the egg is fertilized.

CORPUS LUTEUM The structure in the ovary that remains after ovulation and secretes progesterone.

Although both ovaries can release eggs during the same cycle, they typically take turns and only one egg is released per cycle. In about 1% of cycles, however, there are multiple ovulations, in which case fraternal twins, triplets, or higher multiples can develop. (Identical twins occur when a single egg is released and fertilized and then splits into two embryos early in embryonic development.)

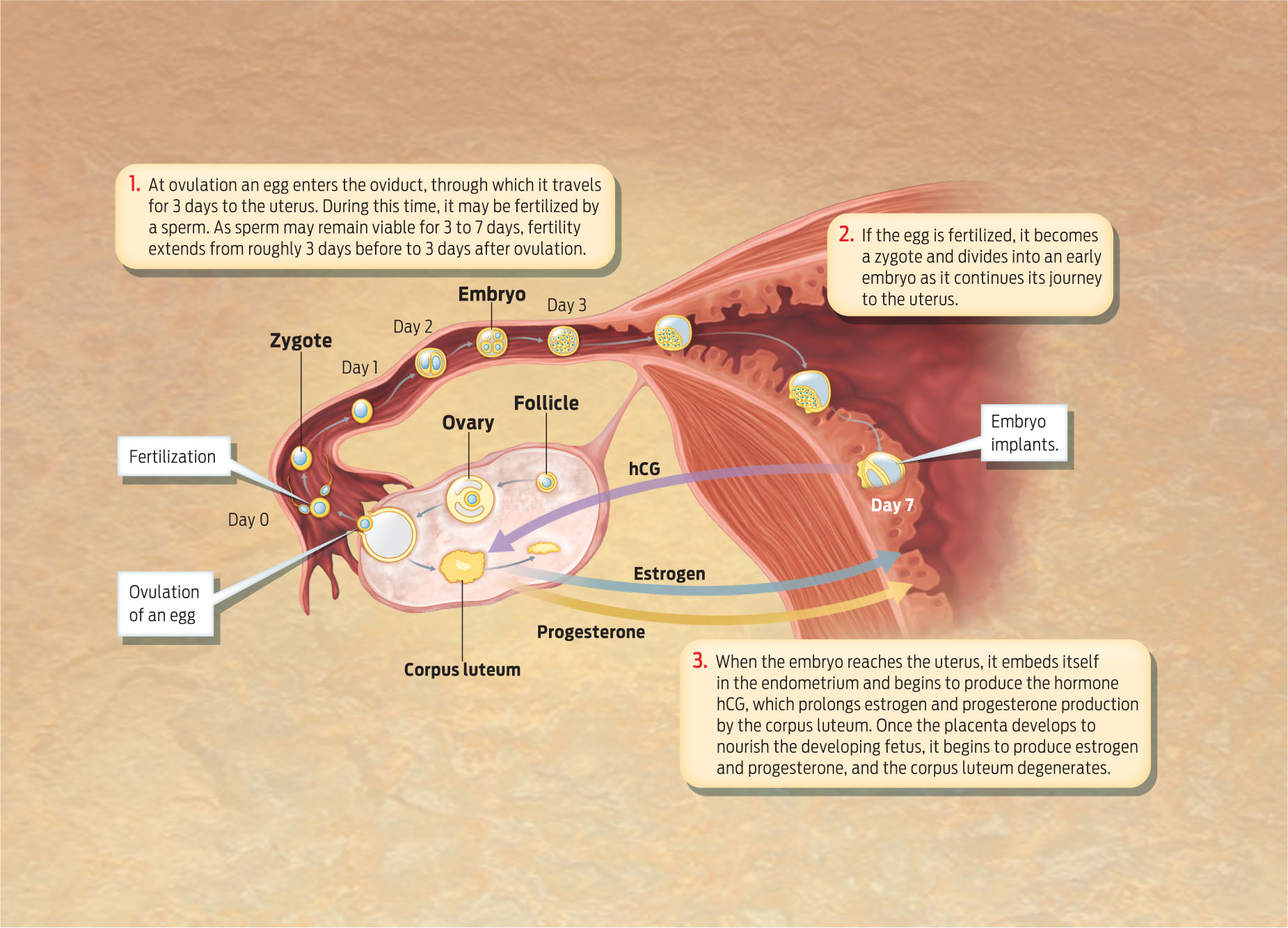

Ovulation presents a crucial time window during which a woman can become pregnant. Sperm must swim through the cervix and uterus and into the oviduct containing the released egg in order to fertilize it. Because sperm can survive in the female reproductive tract anywhere from 3 to 7 days, a woman can become pregnant even if she has sex before she ovulates. Sperm can in effect wait in the oviduct for an egg to be ovulated. Once the egg leaves the oviduct, however, the odds that it will be fertilized are extremely small.

MENSTRUATION The shedding of the uterine lining (the endometrium) that occurs when an embryo does not implant.

If an egg is not fertilized within 24 hours of ovulation, it is no longer viable. The corpus luteum degenerates at about day 26 of the cycle, progesterone levels drop, and the uterine lining sloughs off, leading to menstruation (INFOGRAPHIC 30.5).

A complex interplay of hormones from the hypothalamus, anterior pituitary gland, and ovaries drives the monthly female reproductive cycle.

ZYGOTE A fertilized egg.

HUMAN CHORIONIC GONADOTROPIN (HCG) A hormone produced by an early embryo that helps maintain the corpus luteum until the placenta develops.

If the egg is fertilized it becomes a zygote, As the zygote travels to the uterus it begins dividing and developing into an embryo. In ideal circumstances, the embryo implants in the endometrium of the uterus about 1 week after the egg is fertilized. Once implanted in the uterus, the embryo secretes a hormone called human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which signals the corpus luteum to continue producing progesterone, which supports the thickening endometrium. This is the hormone that, in effect, tells the reproductive system that pregnancy has begun (hCG is the hormone that most pregnancy tests use as a marker to detect a pregnancy).

PLACENTA A structure made of fetal and maternal tissues that helps sustain and support the embryo and fetus.

FETUS After the eighth week after fertilization, the embryo is referred to as a fetus.

Once the embryo implants, embryonic and maternal endometrial tissues interact to form the placenta, a disc-shaped structure that provides nourishment and support to the developing fetus. In addition to delivering oxygen, nutrients, and other key molecules like antibodies from the mother that help protect the embryo against infections, the placenta eventually takes over from the corpus luteum the task of producing estrogen and progesterone (INFOGRAPHIC 30.6).

Estrogen and progesterone support the implanted embryo as it develops. Early in pregnancy, the embryo secretes human chorionic gonadatropin (hCG), which signals the corpus luteum to continue to produce these hormones. The placenta, once it has formed, takes over estrogen and progesterone production.

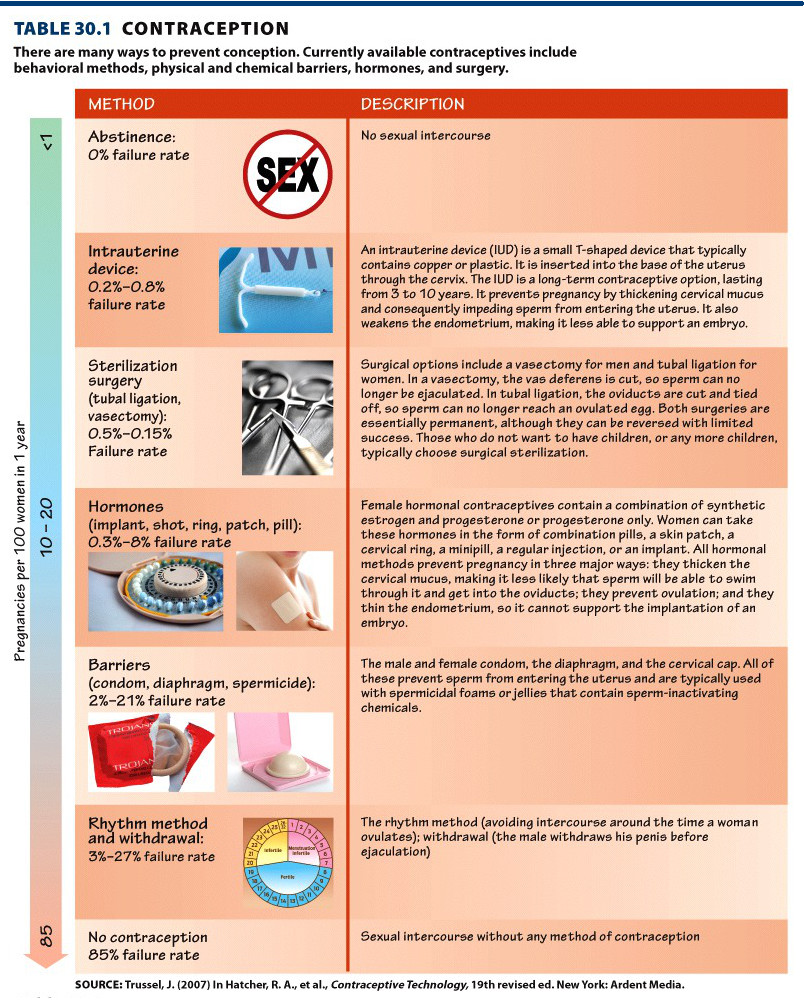

CONTRACEPTION The prevention of pregnancy through physical, surgical, or hormonal methods.

Even if a woman never becomes pregnant, her hormonal cycles will continue until the ovaries stop responding to follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone at the time of menopause, which in American women occurs at about age 51; at this time women stop ovulating and stop having monthly reproductive cycles, and are therefore no longer able to conceive.

Because hormones play such a crucial role in pregnancy and reproduction, many types of contraception are designed to interfere with the normal female hormone cycle (TABLE 30.1) . Most birth control pills contain both estrogen and progesterone at levels that prevent the anterior pituitary from releasing follicle-stimulating and luteinizing hormones. This prevents ovulation and consequently a woman taking this pill does not release eggs. Progesterone in birth control pills prevents successful pregnancy in other ways, too: it thickens the cervical mucus, blocking sperm from entering the uterus and oviducts, and also reduces endometrial thickening—a process that is necessary to support an embryo.

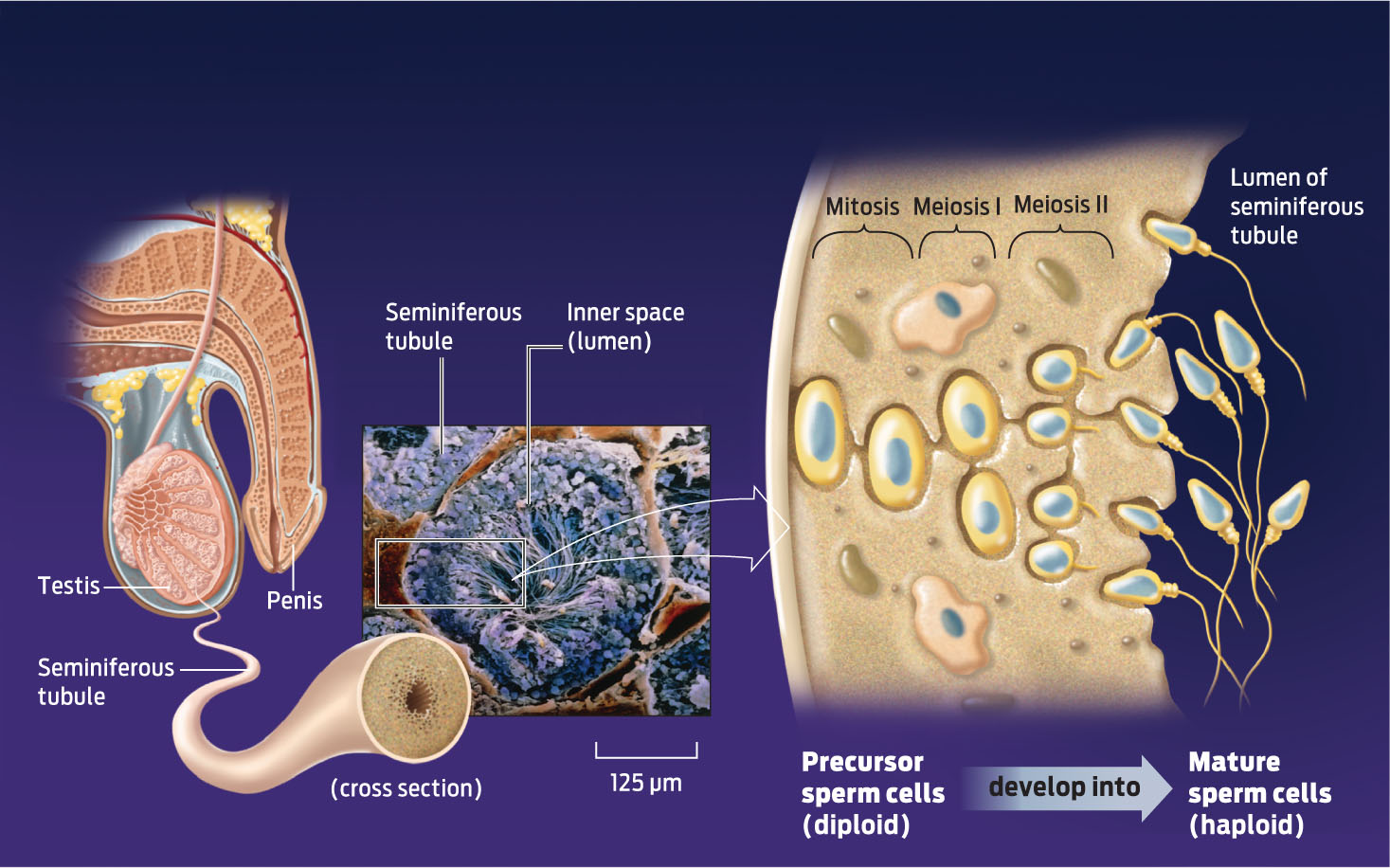

Men do not have a monthly hormone cycle, but beginning at puberty, sperm go through recognizable stages of development. The seminiferous tubules house precursor sperm cells that go through meiosis (see Chapter 11) and specialization to produce mature sperm cells. It takes approximately 6 weeks for sperm to mature. Maturation is stimulated by testosterone, and although men produce testosterone continuously throughout their adult lives, they produce slightly less of the hormone as they age and consequently sperm production declines over time (INFOGRAPHIC 30.7).

Within seminiferous tubules in the testes, precursor cells are stimulated by testosterone to go through cell division (meiosis) and cell differentiation to develop into sperm. While the entire process takes approximately 6 weeks, because cells are in various stages of development a continuous supply of sperm is produced.