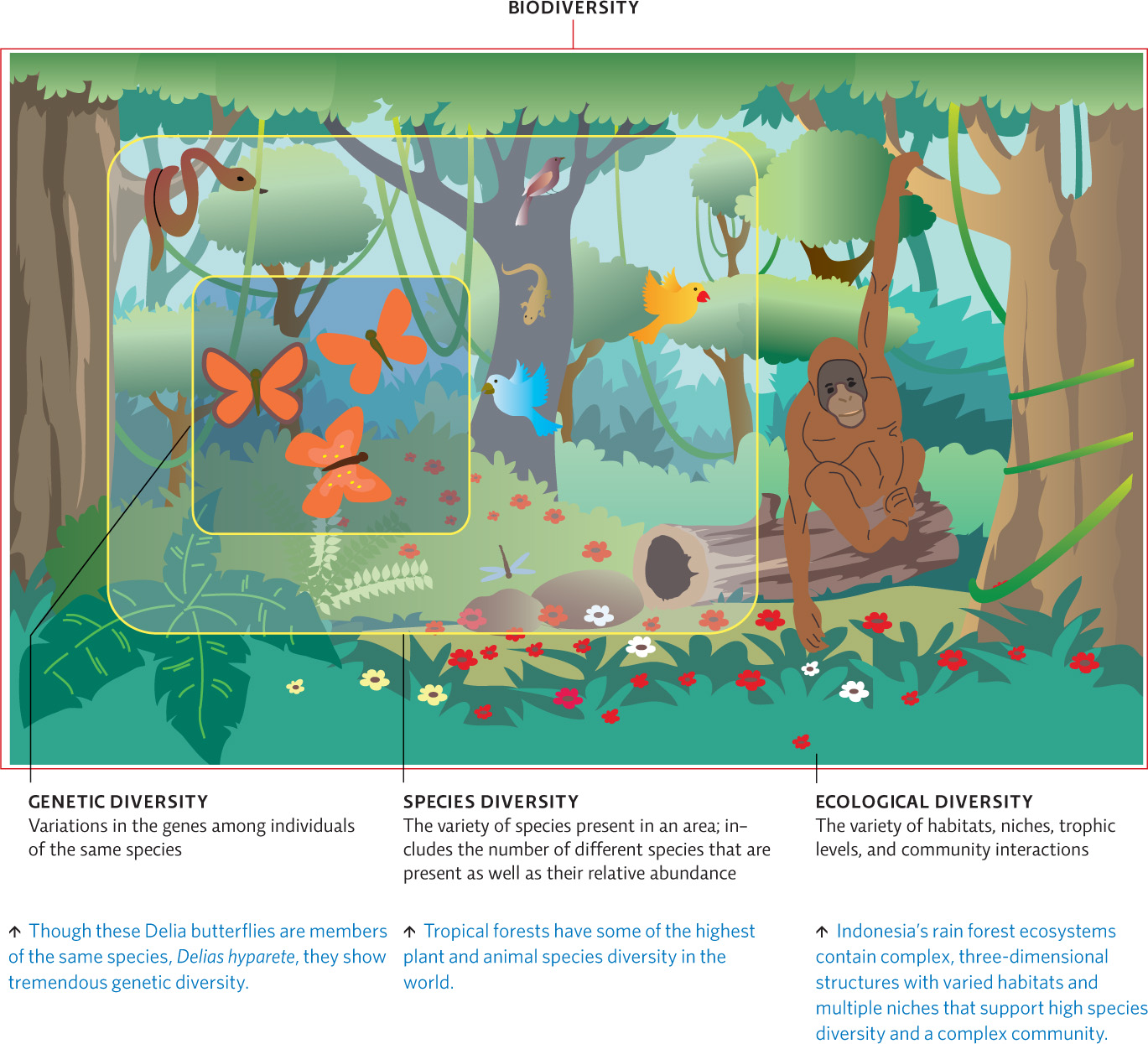

Biodiversity includes variety at the individual, species, and ecosystem levels.

Biodiversity can be broken down into three types of diversity that really represent three different levels of diversity, from the population up to the ecosystem. Genetic diversity is the heritable variation among individuals of a single population or within the species as a whole. This is diversity at the population level. Genetic diversity provides the raw material that allows populations to adapt to their environment (potentially leading to the emergence of new species). Without genetic diversity, even the most well-adapted species could be in danger of facing extinction if conditions change.

genetic diversity

The heritable variation among individuals of a single population or within the species as a whole.

KEY CONCEPT 12.3

Genetic, species, and ecosystem diversity all enhance the ability of an ecosystem to function as well as increase an ecosystem’s ability to adapt to changing conditions.

The importance of genetic diversity was tragically illustrated in 19th-century Ireland. At the time, potatoes were the main food source for one-third or more of the population. Potatoes grew well in the Irish climate, despite the plant not being native to Ireland—it hails from South America. On the slopes of the Andes mountains, thousands of different genetic varieties of potato plants grew, each adapted to the slightly different niche found at different latitudes and elevations, traits that were selected for by nature and later enhanced with artificial selection by hundreds of generations of Andean farmers. But only a few varieties of potato were imported to Ireland, and by the 1840s, only two types were planted, predominately one variety called the “lumper.” These varieties grew well and fed millions until a fungus arrived (probably on ships from North America) in the mid-1800s and attacked potatoes. In the Andes, this fungus would damage some crops, but because all the potato varieties were so different, even if some plants died, others would survive. But in Ireland, without genetic diversity in the potato “population,” most of the potato plants were identical, and so what killed one killed them all. The vulnerable lumper succumbed to the fungus, and the potato crop was wiped out for several years. Between 1845 and 1851, more than 1 million people died of starvation and 1 million more emigrated (many to the United States).

We can also find biodiversity at the community level— that is, species diversity. This is an accounting of the number of species living in an area (richness) and their distribution (evenness) (see Chapter 10). Some ecosystems naturally have higher species diversity than others. Areas with high species diversity often owe that variety to their ecological diversity—the variety of habitats, niches, and ecological communities in an ecosystem. Rain forests contain a wide variety of habitats and considerable physical complexity, creating lots of niches. Each of the many species living in a tropical rain forest occupies an individual niche, and they all contribute to the functioning of the ecosystem (including vital services like energy capture and nutrient cycling, decomposition, and biomass production). For example, a wide variety of plant species occupy every level of the rain forest, from the forest floor to the canopy, and they capture varying amounts of sunlight. This large producer base supports many trophic levels and many species within those trophic levels, increasing the efficient use and transfer of nutrients in the ecosystem. Few matter resources will go unused. The loss of species (extinction) in an ecosystem removes contributing members from that ecosystem, potentially impacting other species and the ability of that ecosystem to function and provide ecosystem services. INFOGRAPHIC 12.3

species diversity

The variety of species, including how many are present (richness) and their abundance relative to each other (evenness).

ecological diversity

The variety within an ecosystem’s structure, including many communities, habitats, niches, and trophic levels.

Give an example of genetic diversity and species diversity from the grocery store produce section.

The wide variety of apples in the grocery store is an example of genetic diversity whereas the variety of fruit in general is an example of species diversity.

KEY CONCEPT 12.4

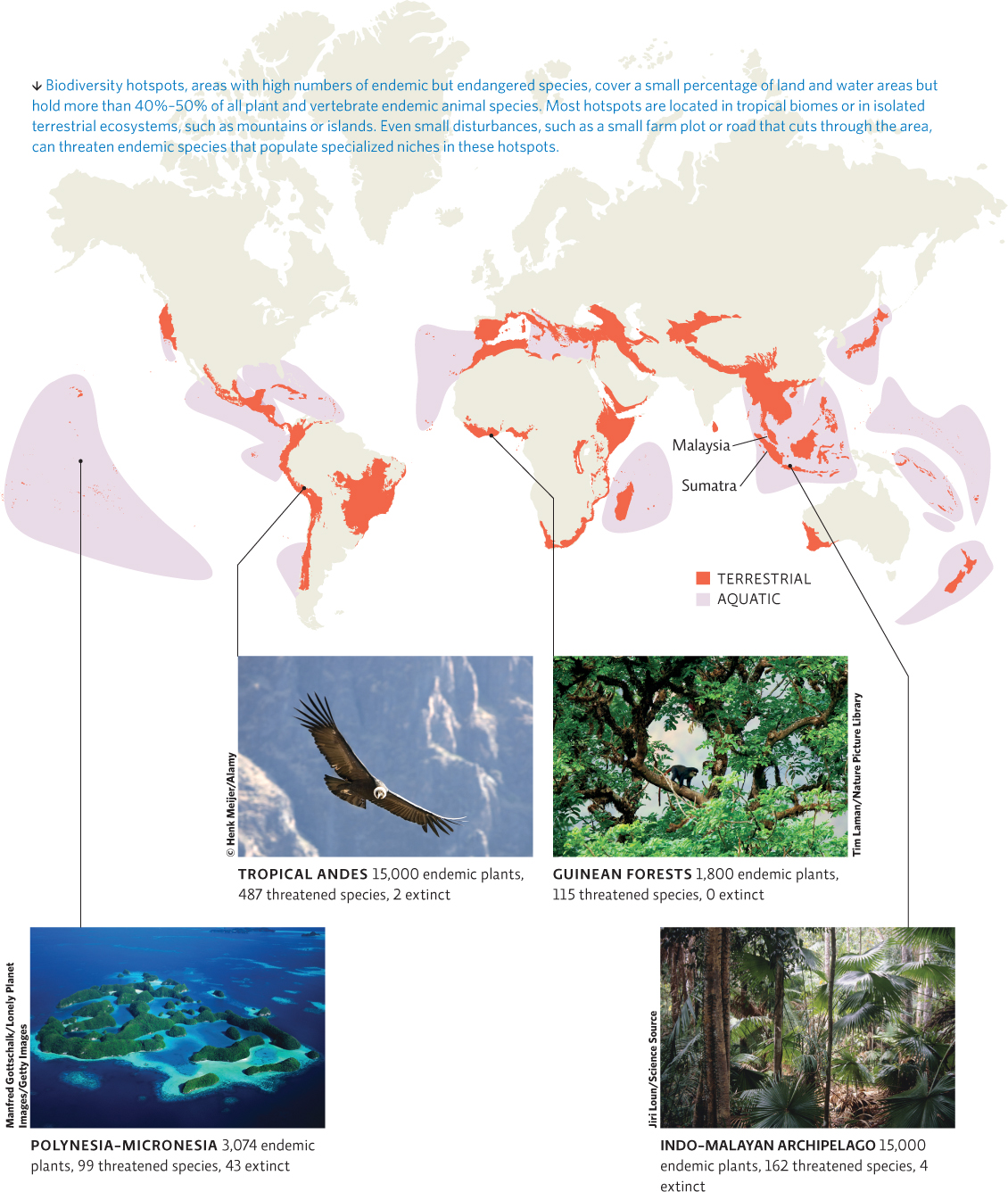

Protecting biodiversity hotspots, areas with high numbers of endangered endemic species, can be a cost-effective way to protect a large number of endangered species.

Tropical forests tend to be particularly flush with both ecological and species diversity, thanks largely to the abundant sunlight and climatic conditions conducive to growth. The forests that are currently being laid low in Sumatra are no exception. They have been left unhampered for so many millennia that these steamy amphibious ecosystems swarm with a cornucopia of life: elephants, orangutans, tapirs, tigers, and every manner of bird and beetle the human imagination can fathom. “The truth is, no one has any idea how many species used to live here,” Sutherlin says. “Half the species in these forests have yet to be described to science.”

In one stunning example of how ecological diversity yields biodiversity, researchers examined 14 different 1-hectare (2.5-acre) study plots in a cloud forest in Peru’s Manu National Park, a biodiversity hotspot. The plots were spaced out across a ridge that climbed from 750 to 3,400 meters (2,500 to 11,000 feet) elevation, and the species diversity found in those altitude differences was stunning—more than 1,000 different tree species alone, in addition to other plants and animals.

Since areas with high ecological diversity offer so many unique habitats and niches, they often have a large number of endemic species that are specially adapted to that locale and naturally found nowhere else on Earth. They are most commonly found in small isolated ecosystems (islands, mountaintops) because the species’ population members cannot easily disperse and share genes with other populations. Biodiversity hotspots are areas that have high endemism but also contain a large number of endangered species (those at risk of becoming extinct). Many are found in tropical regions. INFOGRAPHIC 12.4

endemic species

A species that is native to a particular area and is not naturally found elsewhere.

biodiversity hotspot

An area that contains a large number of endangered endemic species.

endangered species

Species at high risk of becoming extinct.

Biodiversity hotspots, areas with high numbers of endemic but endangered species, cover a small percentage of land and water areas but hold more than 40%-50% of all plant and vertebrate endemic animal species. Most hotspots are located in tropical biomes or in isolated terrestrial ecosystems, such as mountains or islands. Even small disturbances, such as a small farm plot or road that cuts through the area, can threaten endemic species that populate specialized niches in these hotspots.

© Henk Meijer/Alamy

Tim Laman/Nature Picture Library

Manfred Gottschalk/Lonely Planet Images/Getty Images

Jiri Loun/Science Source

Many hotspots are in tropical areas, but some are also found in areas further north and south of the equator. Why do you suppose so many non-tropical coastal areas are biodiversity hotspots?

These areas represent the meeting place of two different biomes and as such may have higher ecosystem diversity (and more species diversity) than an area at the same latitude but not adjacent to land or water. In addition, coastal areas have been settled by humans for a long time so may have been posing a threat to species for some time. Today these areas are heavily settled and our impact is likely to be increasing.

The island of Sumatra is one such hotspot; it is home, for example, to the endemic Sumatran Tiger. The pygmy elephant is likewise endemic to the nearby island of Borneo. And the orangutan, one of humans’ closest relatives on the evolutionary tree, is endemic to the region, with different types of orangutan found on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo. All three of these species are being driven to the edge of extinction by our pursuit of palm oil.