Sustainable palm oil may protect biodiversity.

The three most common cultivars (strains) of oil palm trees that are routinely planted are dura, pisifera, and a hybrid between the two called tenera. The tenera is considered the best of the three because it yields the most oil—30% more than either of its siblings, by most estimates. “They’re known as farmers’ gold,” says Raviga Sambanthamurthi, a geneticist with the Malaysian Palm Oil Board.

Scientists knew for many years that these “golden” fruits were the result of variations of a single gene, Sambanthamurthi says. But they didn’t know which gene or how to screen for it. That left farmers with some dismal options. The tenera variety is produced by manually cross-breeding the other two strains, which is easy enough. But farmers usually have to wait 5 or 6 years, until the oil palm plants bear fruiting bunches, before they can tell how successful they’ve been and how many tenera plants they’ve got.

KEY CONCEPT 12.7

Effective biodiversity protection programs must address the needs of humans as well as the ecosystems and species that are in danger.

So Sambanthamurthi was thrilled when she and her team of researchers discovered the SHELL gene, back in 2012, which is directly responsible for the tenera fruit, with its thin shell and high oil content. The discovery equips farmers with the ability to identify the tenera seeds before planting. “That puts years back on the clock,” she says. “It enables farmers to produce more oil per hectare. And that means it reduces the pressure to clear virgin forest.” It was the dream of making such a significant contribution as this that drove Sambanthamurthi to return to her native Malaysia and join the research division of the country’s Palm Oil Board, after completing her PhD in genetics at the University College of London. “I knew if I was I going to make difference, it would be in palm oil,” she said. “Sustainable palm is the key to protecting our biodiversity, and our heritage.”

In Sumatra and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, the solution to protecting biodiversity will have to involve palm oil production. As Sambanthamurthi and others point out, it’s the most productive oil-bearing crop at our disposal. It claims just 5% of the total vegetable oil acreage globally but accounts for the production of roughly one-third of all vegetable oil, making it the biggest single source of edible oil worldwide. Soybeans, by comparison, account for 41% of the total vegetable acreage and yet produce only 27% of the world’s edible vegetable oil. “To get the same amount of soybean oil, you would have to use ten times as much land. So really, it’s the best option we have environmentally as well.”

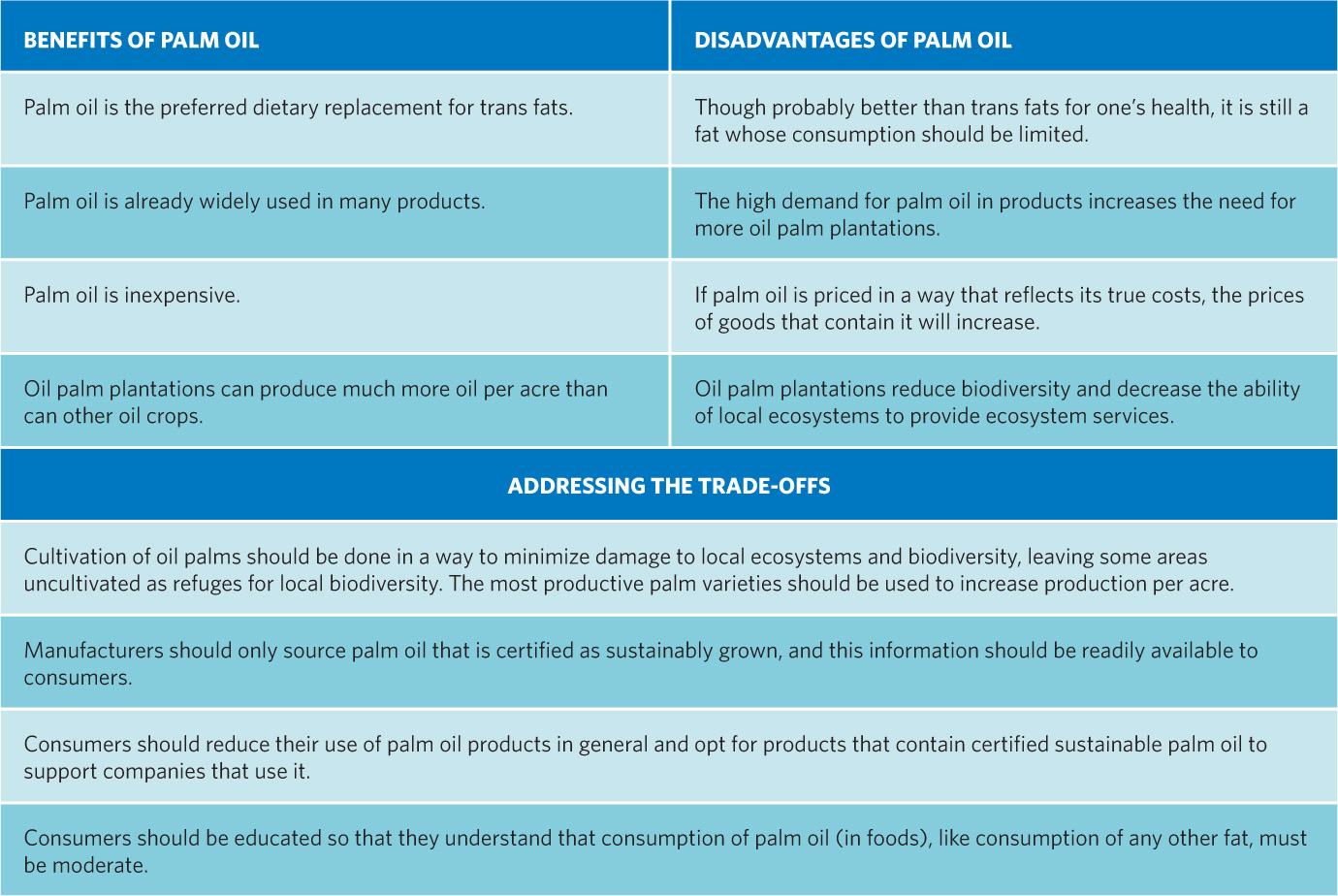

There are ways to produce palm oil sustainably. To be certified sustainable by the nonprofit group Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), palm oil producers must adhere to certain practices that minimize the use of fire and pesticides, and they must take steps to prevent soil erosion and water pollution. The rights of workers (fair wages and good working conditions) are a high priority, and the local community is given an opportunity to weigh in on proposed oil palm plantations. In addition, growers cannot clear old-growth forests or those with high biodiversity or cultural value to use for plantations. Sutherlin and others say the reasons for adopting those methods are clear: If we factor in the value of services provided by intact ecosystems, sustainably produced palm oil is significantly cheaper than non-sustainably produced product (true cost accounting; see Chapter 6). In fact, production methods that destroy ecosystems and drive species to extinction incur costs that we may never be able to repay. Only a careful and honest analysis of the trade-offs of using palm oil will help us decide how best to proceed. TABLE 12.1

Deciding how to proceed with regard to palm oil requires that we evaluate the trade-offs of our choices and that we strike a balance between meeting our desire for palm oil and the survival of the ecosystems and local communities affected by its cultivation.

What role does the consumer play in the future course of the palm oil industry and what can manufacturers of products that contain palm oil do to help consumers make informed decisions? How can producing palm oil that is sustainably certified help address some of the disadvantages of using palm oil?

Answers may vary. Student might feel that consumers should take the time to research companies or read labels to see what products they use contain palm oil and which brands contain sustainably sourced palm oil. They might advocate boycotts or organized campaigns against those companies that do not use sustainably sourced palm oil. Companies should make this information readily available and easy to understand. Consumers should be prepared to support companies who use sustainable sources of palm oil, even if it means paying higher prices.

But for oil producers to adopt better ways, demand will have to come from consumers. “Companies aren’t hearing from their customers,” Sutherlin says. “They tell us flat out ‘We know it’s bad. We know it’s doing all these horrible things to the environment. But it’s our cheapest option, and no one’s threatening to boycott us over it.’“In 2013, Sutherlin’s organization, the nonprofit Rainforest Action Network, launched the “Snack Food 20” campaign—a call on the top 20 global snack food companies, including Krispy Kreme, Kraft, Kellogg, Heinz, General Mills, and Nestle, to use only sustainably produced palm oil in its products (certified by the RSPO).

Others have taken up the cause as well. In 2010, New York Comptroller Thomas Di Napoli, who manages investments for the state’s $153 billion pension fund, won pledges from companies like Dunkin’ Donuts, Sara Lee, and Smucker’s to only use sustainably produced palm oil. Unilever, maker of food and cleaning products, advertises that it is now sourcing only sustainable palm oil. And since at least 2007, two Michigan Girl Scouts have been lobbying the Girl Scouts U.S.A. to extract a similar pledge from the makers of Girl Scout cookies. Like so many other processed food manufacturers, the Girl Scouts switched to palm oil so the cookies would be free of trans fats. The organization says it would like to switch to sustainably produced palm oil, but so far there simply isn’t enough of it out there. In any given year, Girl Scouts sell hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of cookies. That’s a lot of palm oil. “Girls sell cookies from Texas to Hawaii and those cookies have to be sturdy,” Amanda Hamaker, product sales manager for Girl Scouts USA, told the Wall Street Journal last year. Right now, only about 6% of today’s global supply is sustainably grown, but that is increasing; 2014 saw record increases in certified sustainable palm oil sales worldwide.

One thing is certain: There is still much value in saving these forests. Orangutans still swing freely through the canopies, and new species of lizards and birds continue to be discovered. Despite the destruction plaguing Indonesia’s forests, all hope is not yet lost.

Select References:

Fitzherbert, E. B., et al. (2008). How will oil palm expansion affect biodiversity? Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 23(10): 538–545.

Gibson, L., et al. (2013). Near-complete extinction of native small mammal fauna 25 years after forest fragmentation. Science, 341(6153): 1508–1510.

Hadi, S. T., et al. (2009). Tree diversity and forest structure in northern Siberut, Mentawai islands, Indonesia. Tropical Ecology, 50(2): 315–327.

Mora, C., et al. (2011). How many species are there on Earth and in the ocean? PLoS Biology 9(8): e1001127. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127

Pimm, S., et al. (2006). Human impacts on the rates of recent, present, and future bird extinctions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(29): 10941–10946.

Singh, R., et al. (2013). The oil palm SHELL gene controls oil yield and encodes a homologue of SEEDSTICK. Nature, 500(7462): 340-344.

Swaddle, J. P., & S. E. Calos. (2008). Increased avian diversity is associated with lower incidence of human West Nile infection: Observation of the dilution effect. PLoS ONE, 3(6): e2488. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002488

Teoh, C. H. (2010). Key Sustainability Issues in the Palm Oil Sector. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Turner, E. C., & W. A. Foster. (2009). The impact of forest conversion to oil palm on arthropod abundance and biomass in Sabah, Malaysia. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 25: 23–30.

PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

Species and habitats provide numerous benefits to people, including water and air purification, food sources, recreation, and medicine. Unfortunately, many species are facing threats at ever-increasing levels. The good news is that we as a society have a direct impact on these threats and can make changes to ensure the survival of many of our at-risk species.

Individual Steps

•Don’t buy products made from wild animal parts such as horns, fur, shells, or bones. Only buy captive-bred tropical aquarium fish, not wild-caught fish.

•Visit the Rainforest Action Network website at http://ran.org/conflict-palm-oil and read about their Snack Food 20 campaign. Is this something you would support?

•Make your backyard friendly to wildlife, using suggestions from www.nwf.org.

•Install an Audubon Guide app on your smartphone, or buy a field guide to learn the plant and animal species in your area.

Group Action

•Work with faculty and other students to organize a bioblitz for a protected area in your region. A bioblitz, which is an intensive survey of all the biodiversity in the area, can generate a large amount of data to be used for habitat management and species protection.

•Join a citizen science program monitoring wildlife. Many regional conservation groups have monitoring opportunities and provide training. For national programs, see the Cornell Lab of Ornithology website at www.birds.cornell.edu and the Izaak Walton League website at www.iwla.org.

Policy Change

•The Endangered Species Act was the first U.S. legislation established to protect species diversity. To learn more about current challenges and updates to the program, visit www.epa.gov/espp.