Mining also comes with significant social consequences.

When a Canadian-based mining giant arrived in Cabanas, El Salvador, wanting to build a large, open-pit gold mine, area residents were wary. They knew from the experience of neighbors that such an operation could divert water from their farms, pollute their air and streams, and threaten their crops. So they formed an environmental group and began protesting. Their own government listened—denying permits to the company in response to public pressure. But the cost of that success proved exorbitant. “[Four] people involved in the opposition to mining in El Salvador [were] killed,” says Keith Slack, senior policy advisor for Oxfam America. The victims included a college student, a pregnant mother, and a community leader and environmental activist who had led some of the anti-mine protests, and whose body was found in 2008, showing signs of having been tortured.

The thread between mining and violence runs long, spans the globe, and involves a range of minerals—from gold and silver to diamonds and emeralds. And it’s not just protesters who suffer. Independent diamond miners in Zimbabwe have also been assaulted and threatened—by security guards working for larger-scale mines whose operators want to maintain a monopoly on the region’s treasures. Elsewhere in Africa, diamonds harvested from areas controlled by warlords—known as “blood diamonds” or “conflict diamonds”—have been used for ages to support armed conflicts, conflicts that have devastated the lives of millions of people.

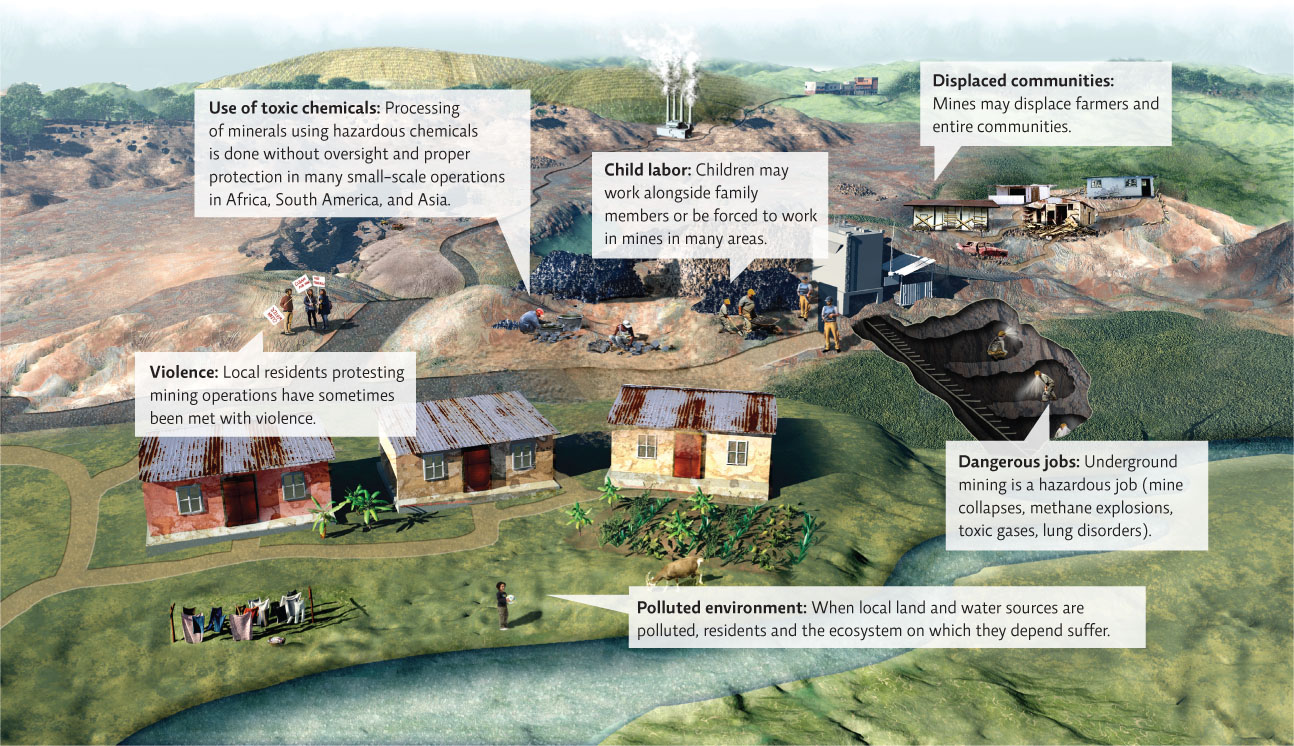

Such violence underscores a point that has long been central to any discussion of minerals’ true costs: The environment is not the only casualty. (See Chapter 6 for more on true cost accounting.) Human health and human rights take a bruising, too, especially in developing countries that lack the resources and infrastructure to regulate such behemoth industries. Not only do mines frequently displace communities in these countries—clearing land, polluting water, and filling the air with noise and dust—but the owners of large industrial mines are notorious human rights violators. They don’t generally give area residents a say in the decision to open a mine in a given location. Nor do they typically clean up the pollution after the minerals have all been harvested, nor compensate communities for the loss of land or ecosystem services.

In addition to all of that, some mining companies routinely violate child labor laws. The International Labor Organization reports that tens of thousands of children work in gold mines—roughly 25% of them in the Sahel region of Africa. Their small size makes them particularly useful in underground mines; unfortunately, their developing bodies are very vulnerable to the dust and chemicals they breathe in as they work. INFOGRAPHIC 26.7

Human rights violations associated with mines, such as displacement, violence, and child labor, are perhaps the most troubling by-products of mining for mineral resources.

Why do you think human rights violations in the mining industry continue to be a problem in the modern world?

Answers will vary. Many of these violations occur in impoverished regions without strong human rights protections in place. But even in developed nations, mining can negatively impact local communities because profits are put before the needs of individuals.

KEY CONCEPT 26.7

Mineral mining has negative social impacts, including health problems for miners and community members, the use of child labor, and outright violence to those who oppose mining.

Even for adults, the work is dangerous. Underground mines can collapse, or develop pockets of methane that then cause explosions, or gather high concentrations of other hazardous inhalants, leading to lung disorders and other illnesses. And the hazards don’t end when the ore is brought to the surface. In developing countries especially, smaller-scale artisanal miners employ a range of toxic chemicals—mercury and cyanide chief among them—in their own crude smelting processes. These chemicals not only contaminate the soil and water of surrounding communities but also expose miners and processers to toxic fumes. In Colombia alone, there are an estimated 200,000 artisanal gold miners who use their bare hands to mix crushed ore with mercury; mercury concentrations in the air inside such artisanal shops are known to reach 1,000 times the World Health Organization (WHO) limit for exposure.

Safer techniques have been developed. But in many areas of Africa, South America, and Asia, large amounts of mercury—and in some cases cyanide—are still used to process ores containing gold and silver. Simply put: Gold is valuable, and mercury and cyanide are cheap. “The thing to remember is that in so many countries, the people doing the actual mining and processing are poor,” says mining analyst John Kaiser. “They’re running makeshift, often illegal operations, on a shoestring. They don’t have the resources to do it safely.”