Industrial fishing is impacting fisheries worldwide.

KEY CONCEPT 31.1

Fishing has supported human populations for centuries, but modern techniques are decimating some fisheries, a tragedy of the commons.

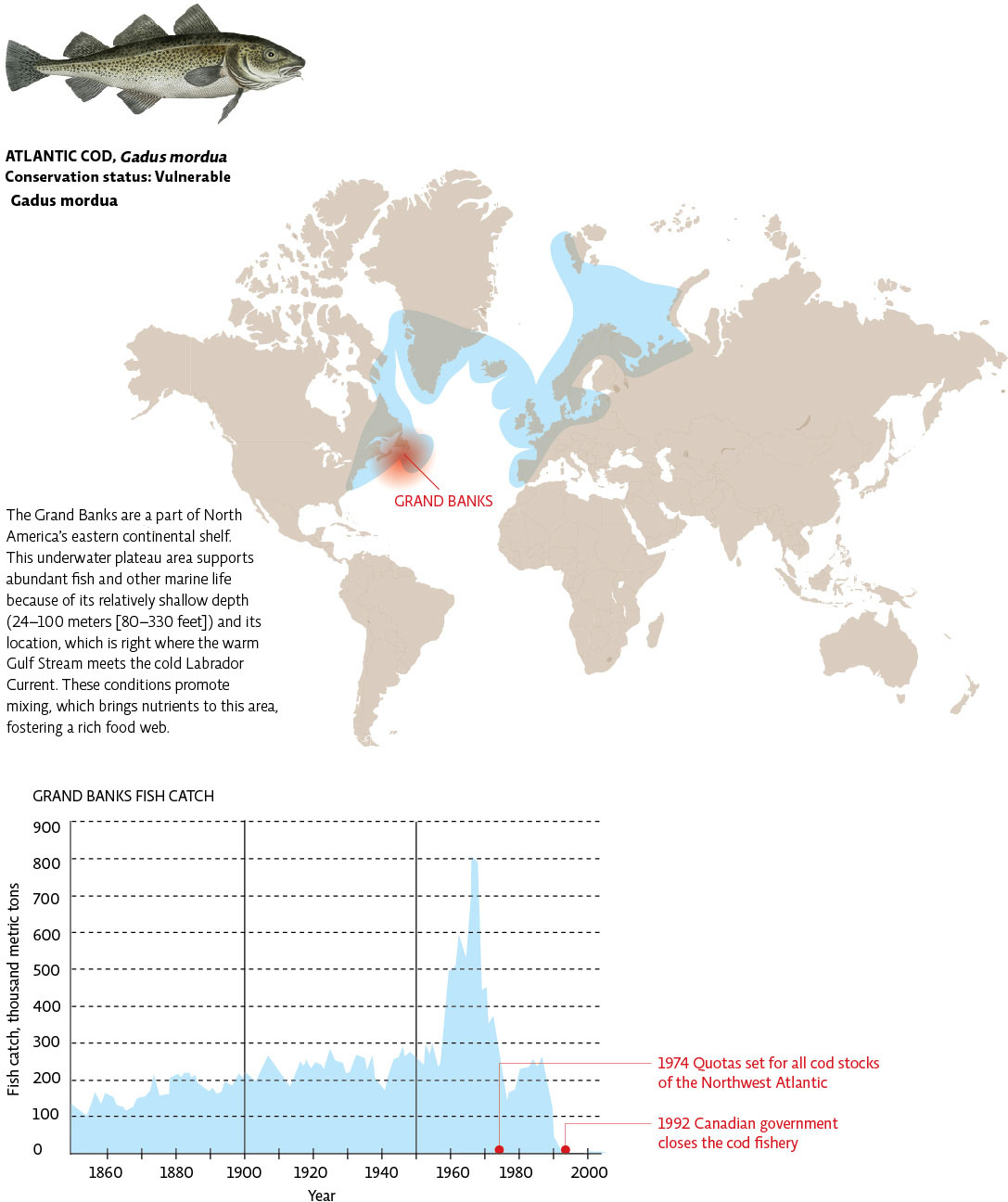

For more than 400 years, the Atlantic cod—a demersal fish, or one that feeds along the ocean floor—supported not just a fishing industry but an entire culture down the northeastern coast of North America. Huge fisheries—places where fish are caught, harvested, processed, and sold and/or shipped—sprang up in the port towns of Massachusetts, Maine, and Newfoundland and were sustained for generations almost exclusively by this one fish. Cod became the namesake of one famous Massachusetts cape town, and it was the source of New England’s early wealth. But in the early 1990s, cod catches declined rapidly. By 1992, when the Canadian government completely closed the Grand Banks region of the Newfoundland–Labrador Shelf to fishing, the annual catch had dropped to just 2% of its historic high. When annual catches fall below 10% of their historic high, scientists call it a collapsed fishery. INFOGRAPHIC 31.1

fisheries

The industry devoted to commercial fishing or the places where fish are caught, harvested, processed, and sold.

collapsed fishery

A fishery in which annual catches fall below 10% of their historic high; stocks can no longer support a fishery.

Cod are cold-water fish that inhabit coastal waters in the North Atlantic (they are also found in the Pacific). They are usually found in waters 10 to 200 meters deep and live close to the sea floor. Adults eat a wide variety of fish (including other cod) as well as mussels, squid, and crab. Their diet and early life-cycle stages depend on a seabed with a complex structure (lots of hiding places and niches for their prey); therefore, trawling methods that drag a heavy net across the sea floor seriously degrade their habitat and spawning beds. The cod fishery has declined throughout its Atlantic range (blue area), especially in the Grand Banks of the Newfoundland-Labrador Shelf region, where the fishery is seriously depleted

The collapse of the Grand Banks fishery was surprising, considering the biology of this fish. Cod are quite large-an adult can be more than 2 meters (6 feet) long and weigh 90 kilograms (200 pounds) or more. When one considers that spawning schools of more than a hundred million fish have been observed and that the average female can spawn millions of eggs, it is hard to imagine that our fishing practices could devastate this population. And yet, they did.

Advanced fishing techniques began being used for cod fishing in the Grand Banks around 1960. How much higher was the fish catch at its peak than the “average” fish catch (~200,000 metric tons) prior to 1960? How did fish catch change after its peak?

The catch was around 800,000 metric tons in 1969. This is 4 times more than the average catch in the decades before 1960. Catch dropped rapidly after the peak; the fishery was closed in 1992, just 23 years after this peak.

More than 20 years later, with the moratorium still in place, the Grand Banks Atlantic cod fishery has yet to recover. Cod population estimates still hover at around 30% of what would be needed for the fishery to survive commercial fishing pressure. Meanwhile, some 40,000 people are still out of work and reliant on government support.

How did this happen? The short answer is that nobody owns the ocean. For an individual fisher, the choice is simple: “If I don’t take it, someone else will.” It doesn’t make sense to leave any fish behind, when the immediate value of taking the fish is greater than the immediate cost, even if it means that there will be fewer fish to harvest in the future. (See Chapter 6 for a discussion of “discounting the future.”) As discussed in Chapter 1, this conundrum is a case of the tragedy of the commons: Any resource to which a group of people have free access (a common) is likely to become overexploited and degraded (the tragedy) as each seeks to maximize personal benefit without consideration for the needs of others.

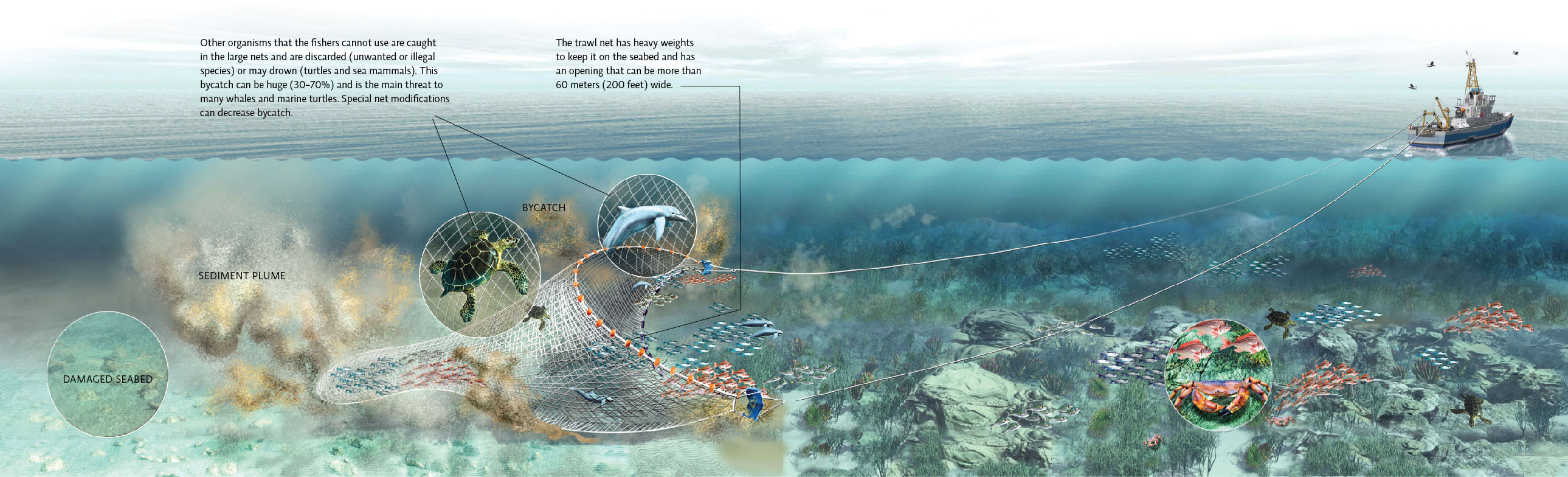

The longer answer to the problem of fisheries collapse involves a constellation of forces. A trifecta of technological advances—steam engines, flash freezing, and trawler ships that could drag huge nets behind them—enabled fishers to travel further into the ocean, catch more fish, and transport them greater distances than ever before. At the same time, health-conscious eating patterns made fish more popular than any other source of protein. And as technology, rising demand, and the tragedy of the commons conspired, the once-prolific Grand Banks Atlantic cod fishery was decimated. Not only did fish populations plummet, but the increased traffic of fuel-guzzling ships polluted the water. Bottom trawlers are particularly damaging. They destroy the sea beds, which are the cod’s spawning grounds, and catch or destroy billions of coral, sponges, starfish, and other invertebrates.

… as technology, rising demand, and the tragedy of the commons conspired, the once-prolific Grand Banks Atlantic cod fishery was decimated.

Other marine species that lived in the same waters were lost as bycatch, meaning they were trapped in nets meant to capture cod. Bycatch seriously threatens many species today, including small whales and dolphins (more than 300,000 taken per year), sea turtles (more than 250,000 taken per year), and even sea birds (more than 300,000 taken per year). Seals, sea lions, and sea otter populations have declined tremendously (by as much as 85%) in some areas due to bycatch. Nontarget fish are also taken as bycatch, including sharks, rays, and juvenile fish of many species, even cod. Bycatch is also a problem with other industrial fishing techniques, such as long-line fishing (a main line holds hundreds of individual lines with baited hooks) and drift netting (a free floating net entangles fish; this method was banned in 1992). Fortunately, fishing methods that minimize bycatch are available, and their use is increasing. INFOGRAPHIC 31.2

bycatch

Nontarget species that become trapped in fishing nets and are usually discarded. Some methods, like trawling, have very high bycatch levels, and discards often exceed the actual target species catch.

Bottom trawlers, like those that are used for cod, drag huge nets across the ocean floor, damaging the seabed where cod and other species live and breed.

What problems can the sediment plume produced by bottom trawling cause in the ocean?

It can cover bottom dwelling organisms, smothering them. It can also reduce visibility, impacting species that depend on vision for hunting or foraging. Sediments that float up closer to the surface might also impact photosynthetic plankton by reducing sunlight penetration.

Such is the story of our last wild food. It begins in the depths of the oceans and ends on our dining room tables. But as fish stocks around the world—not only of Atlantic cod, but also of Chilean sea bass, Alaskan pollock, Atlantic herring, and many others—dwindle to unprecedented lows, scientists and fishers alike are trying to rewrite that story. Their success could mean sparing the world’s fisheries from an unthinkable fate; it could also mean that our grandchildren never eat a wild-caught fish.