Carrying capacity: Is zero population growth enough?

Every given environment has a carrying capacity—the maximum population size that the area can support. How large that population can be is determined by a range of forces, including the supply of nonrenewable resources, the rate of replenishment for renewable resources on which we depend, and the impact each individual person has on the environment. (A degraded ecosystem can sustain far fewer people than a well-maintained, healthy one.)

carrying capacity

The population size that an area can support for the long term; depends on resource availability and the rate of per capita resource use by the population.

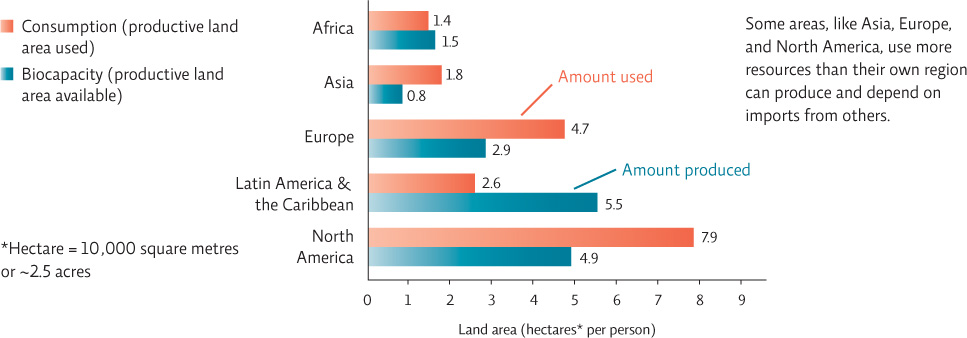

There are roughly 7 billion people on the planet today. Whether we stabilize at 9 or 10 billion or more depends on how quickly we lower TFR to achieve replacement fertility worldwide. Even at 7 billion people, we may have already exceeded the carrying capacity of Earth. One problem we face is our dependence on nonrenewable energy sources; they will not last indefinitely. But we are also overusing our biological resources. There are differences in how well different regions of the world live within the biocapacity (the ability of the ecosystem’s living components to produce and recycle resources and assimilate wastes) of their own environments. North America, and the United States in particular, uses far more resources than its land area can provide, whereas Latin America and the Caribbean use less than half of the biocapacity of their regions. This means nations like the United States and many others are importing resources from other regions. INFOGRAPHIC 4.8

Many ecologists and economists think that, at our current rate of consumption, human population size has already surpassed what the Earth can support in the long term (reduced its “carrying capacity”). This reduces the abillity of the planet to meet our current needs, much less the needs of an ever growing population.

How could the human population increase the ability of the productive land area, a finite, though renewable resource base, to support it?

The productive land available to us can support more people (or support the current population over the long term) if we decrease the resources used per person (less waste, more efficient use of what is here, taking care not to degrade the environment's ability to replace what was taken).

The problem, then, is twofold: On one hand, we are increasing, rapidly, in sheer numbers. On the other, we are consuming more resources per person than ever before.

In general, population increase is a problem of the developing world. The highest fertility rates tend to be in the least developed countries—those that have yet to complete the demographic transition. Overconsumption, meanwhile, is a problem of more developed countries like the United States, where a single person might consume more food, fuel, and other resources (and thus place more strain on the environment) than a whole group of people in a less developed country like Sudan or Bangladesh. The impact humans have on Earth is thus due to a combination of factors: population size, affluence, and how we use resources, especially our use of technology, which tends to increase our overall use of resources. This is discussed more fully in Chapter 6.

In the years since the one-child policy was enacted, China has found itself careening from one end of this spectrum to the other. The problems that come with overpopulation—such as slums, epidemics, overwhelmed social services, and the production of high volumes of waste—have been mitigated by a reduction in the fertility rate. But as fertility has declined, relative affluence has increased, and the Chinese are now straining the environment in a different way: by overconsuming.

KEY CONCEPT 4.8

The number of people Earth can support depends on how many resources each uses. We may have already exceeded our planet’s carrying capacity by using more resources than it can replace in the long term.

It’s important to understand that overconsumption in one region or country can strain carrying capacity in other, disparate regions. In Bangladesh, for example, rising sea levels, spurred by global climate change, are pushing that nation’s carrying capacity to the brink. Most experts agree that a major driver of current climate change is rampant fossil fuel consumption by nations all over the world, many very far from Bangladesh. China now leads the way in the release of fossil fuel-based carbon emissions linked to climate change—because of its huge population and its growing affluence.

Ultimately, the question of how many people the planet can support may not be the right one. Trying to pinpoint whether Earth’s carrying capacity is 7 billion or 9 billion or even 16 billion is meaningless unless we identify what an acceptable quality of life is. And while overpopulation may be an issue that has global significance and causes, it is one that ultimately plays out at the regional level: As land becomes degraded and water supplies become depleted or polluted, people (and other organisms) live in an increasingly impoverished environment.