8.2 Emotional Communication: Msgs w/o Wrds

Leonardo the robot may not be able to feel, but he sure can smile. And wink. And nod. Indeed, one of the reasons why people who interact with Leonardo find it so hard to think of him as a machine is that Leonardo expresses emotions that he doesn’t actually have. An emotional expression is an observable sign of an emotional state, and while robots can be taught to exhibit them, human beings seem to do it quite naturally.

Why are we “walking, talking advertisements” of our inner states?

Our emotional states express themselves in a wide variety of ways. For example, they change the way we talk–from our intonation and inflection to the loudness and duration of our speech–and research shows that listeners can infer emotional states from vocal cues alone with better-

Of course, no part of your body is more exquisitely designed for communicating emotion than your face. Underneath your face lie 43 muscles that are capable of creating more than 10,000 unique configurations, which enable you to convey information about your emotional state with an astonishing degree of subtlety and specificity (Ekman, 1965). Psychologists Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen (1971) spent years cataloguing the muscle movements of which the human face is capable. They isolated 46 unique movements, which they called action units, and they gave each one a number and a name, such as “cheek puffer,” “dimpler,” and “nasolabial deepener” (which, coincidentally enough, are also the names of heavy metal bands). Research has shown that combinations of these action units are reliably related to specific emotional states (Davidson et al., 1990). For example, when we feel happy, our zygomatic major (a muscle that pulls our lip corners up) and our obicularis oculi (a muscle that crinkles the outside edges of our eyes) produce a unique facial expression that psychologists describe as “action units 6 and 12” and that the rest of us simply call smiling (Ekman & Friesen, 1982; Frank, Ekman, & Friesen, 1993; Steiner, 1986).

323

Communicative Expression

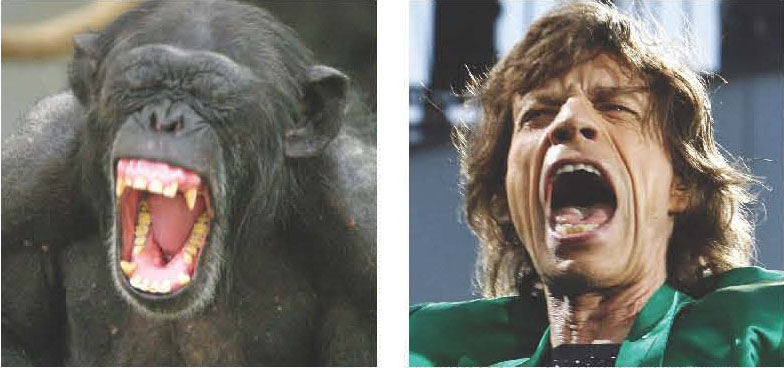

ANDREAS GEBERT/DPA/NEWSCOM

Why are our emotions written all over our faces? In 1872, Charles Darwin published The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, in which he speculated about the evolutionary significance of emotional expression. Darwin noticed that human and nonhuman animals share certain facial and postural expressions, and he suggested that these expressions were meant to communicate information about internal states. It’s not hard to see how such communications could be useful (Shariff & Tracy, 2011). For example, if a dominant animal can bare its teeth and communicate the message, “I am angry at you,” and if a subordinate animal can lower its head and communicate the message, “I am afraid of you,” then the two can establish a pecking order without actually spilling any blood. Darwin suggested that emotional expressions are a convenient way for one animal to let another animal know how it is feeling and therefore how it is prepared to act. In this sense, emotional expressions are a bit like the words of a nonverbal language.

The Universality of Expression

Figure 8.7: Six Basic Emotions Humans all over the globe generally agree that these six faces are displaying anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. What might account for this widespread agreement? Adapted from Arellano, Varona, & Perales, 2008.

Figure 8.7: Six Basic Emotions Humans all over the globe generally agree that these six faces are displaying anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. What might account for this widespread agreement? Adapted from Arellano, Varona, & Perales, 2008.

Of course, a language only works if everybody speaks the same one, which is why Darwin advanced the universality hypothesis, which suggests that emotional expressions have the same meaning for everyone. In other words, every human being naturally expresses happiness with a smile, and every human being naturally understands that a smile signifies happiness.

There is some evidence for Darwin’s hypothesis. For example, people who have never seen a human face make the same facial expressions as those who have. Congenitally blind people smile when they are happy (Galati, Scherer, & Ricci-

What evidence suggests that facial expressions are universal?

324

But not all psychologists are convinced. For example, recent research (Gendron et al., in press) shows that like the South Fore, members of an isolated tribe called the Himba can match faces to emotion words just as Americans do. But when the Himba are instead asked to match faces that are “feeling the same way” to each other, they produce matches that are quite unlike those produced by their American counterparts. Studies such as these suggest that the universality hypothesis may be stated too strongly. At present, we can say with confidence that there is considerable agreement among all humans about the emotional meaning of many facial expressions, but that this agreement is not perfect.

The Cause and Effect of Expression

Members of different cultures express many emotions in the same ways, but why? After all, they don’t speak the same languages, so why do they smile the same smiles and frown the same frowns? The answer is that words are symbols, but facial expressions are signs. Symbols are arbitrary designations that have no causal relationship with the things they symbolize. English speakers use the word cat to indicate a particular animal, but there is nothing about felines that actually causes this particular sound to pop out of our mouths, and we aren’t surprised when other human beings make different sounds–such as popoki or gatto–to indicate the same thing. In contrast, facial expressions are not arbitrary symbols of emotion. They are signs of emotion because signs are caused by the things they signify. The feeling of happiness causes the contraction of the zygomatic major; thus that contraction is a sign of that feeling in the same way a footprint in the snow is a sign that someone walked there.

Of course, just as a symbol (bat) can have more than one meaning (wooden club or flying mammal), so, too, can a sign. Is the man in the photo at left feeling joy or sorrow? In fact, these two emotions often produce rather similar facial expressions, so how do we tell them apart? Research suggests that one answer is context. When someone says, “The centerfielder hit the ball with the bat,” the sentence provides a context that tells us that bat means “club” and not “mammal.” Similarly, the context in which a facial expression occurs often tells us what that expression means (Aviezer et al., 2008; Barrett, Mesquita, & Gendron, 2011; Meeren, Heijnsbergen, & de Gelder, 2005). It is difficult to tell what the man in the photo to the right is feeling. But if you look below and see the photo in context, you will have no trouble. Indeed, when you return here, you may well wonder how you could ever have had any trouble.

Our emotional experiences cause our emotional expressions, but it also works the other way around. The facial feedback hypothesis (Adelmann & Zajonc, 1989; Izard, 1971; Tomkins, 1981) suggests that emotional expressions can cause the emotional experiences they signify. For instance, people feel happier when they are asked to make the sound of a long e or to hold a pencil in their teeth (both of which cause contraction of the zygomatic major) than when they are asked to make the sound of a long u or to hold a pencil in their lips (Strack, Martin, & Stepper, 1988; Zajonc, 1989; see FIGURE 8.8). Similarly, when people are instructed to arch their brows they find facts more surprising, and when instructed to wrinkle their noses they find odors less pleasant (Lewis, 2012). These things happen because facial expressions and emotional states become strongly associated with each other over time (remember Pavlov?), and eventually each can bring about the other. These effects are not limited to the face. For example, people feel more assertive when instructed to make a fist (Schubert & Koole, 2009) and rate others as more hostile when instructed to extend their middle fingers (Chandler & Schwarz, 2009).

325

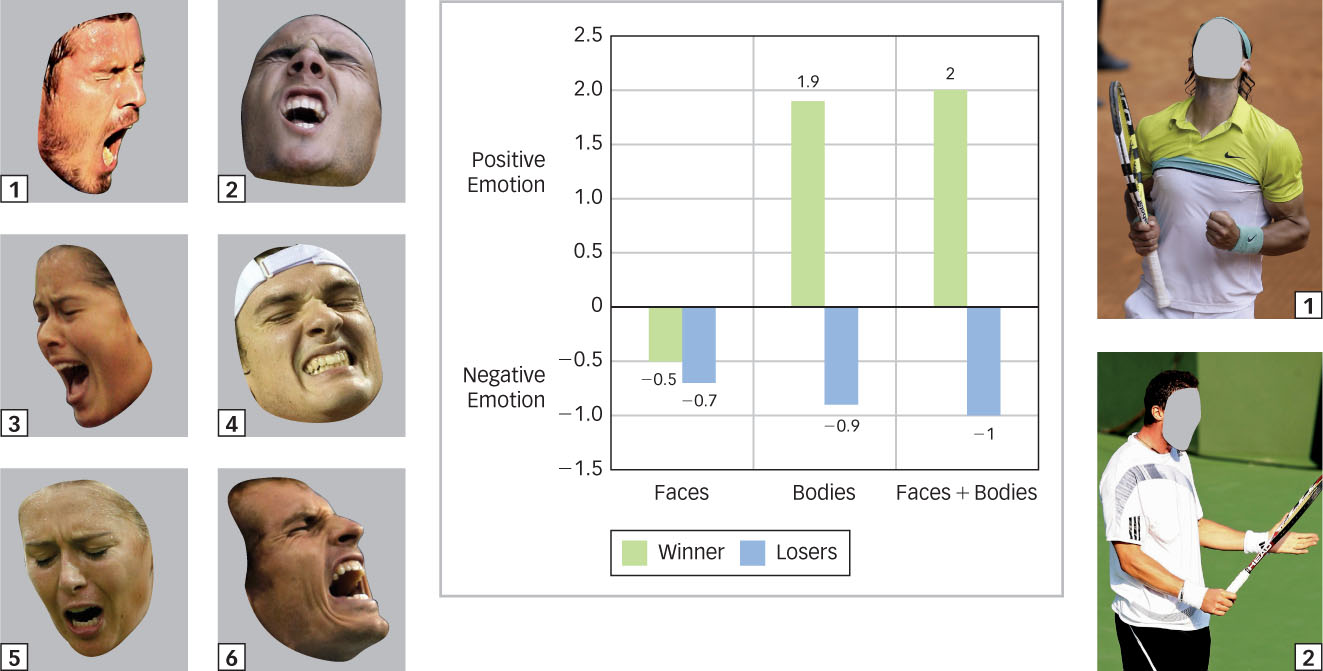

HOT SCIENCE: The Body of Evidence

What can you tell from a face? Much less than you realize. Aviezer, Trope, and Todorov (2012) showed participants faces taken from pictures of tennis players who had either just won a point (Faces 2, 3, and 5 in the figure shown here) or lost a point (Faces 1, 4, and 6) and asked them to guess whether the athlete was experiencing a positive or negative emotion. As the leftmost bars of the graph show, participants couldn’t tell. They guessed that the “winning faces” and the “losing faces” were experiencing equal amounts of somewhat negative emotion.

Next, the researchers showed a new group of participants bodies (without faces) taken from pictures of tennis players who had either just won a point (Body 1 in the figure) or lost a point (Body 2), and asked them to make the same judgment. As the middle bars show, participants were quite good at this. Participants guessed that “winning bodies” were experiencing positive emotions and that “losing bodies” were experiencing negative emotions.

Finally, the researchers showed a new group of participants the athletes’ bodies and faces together. As the rightmost bars show, participants’ ratings of the body-

It seems that facial expressions of emotion are more ambiguous than most of us realize. When we see people expressing anger, fear, or joy, we are using information from their bodies, their voices, and their physical and social contexts to figure out what they are feeling. Yet, we mistakenly believe that we are getting most of our information from their facial expression.

The moral of the story? Next time you want to know how a losing athlete feels, concentrate more on defeat than deface. (Sorry).

AP PHOTO/VICTOR R. CAIVANO

IVAN MILUTINOVIC/REUTERS/CORBIS

BEN NELMS/REUTERS/NEWSCOM

STEFAN WERMUTH/REUTERS/NEWSCOM

MIKE SEGAR/REUTERS/NEWSCOM

AP PHOTO/VICTOR R. CAIVANO

REN LONG/CHINE NOUVELLE/SIPA/NEWSCOM

Why do emotional expressions cause emotional experience?

326

Figure 8.8: The Facial Feedback Hypothesis Research shows that people who hold a pen with their teeth feel happier than those who hold a pen with their lips. These two postures cause contraction of the muscles associated with smiling and frowning, respectively.

Figure 8.8: The Facial Feedback Hypothesis Research shows that people who hold a pen with their teeth feel happier than those who hold a pen with their lips. These two postures cause contraction of the muscles associated with smiling and frowning, respectively.

The fact that emotional expressions can cause the emotional experiences they signify may help explain why people are generally so good at recognizing the emotional expressions of others. Many studies show that people unconsciously mimic other people’s body postures and facial expressions (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999; Dimberg, 1982). When we see someone smile (or even when we read about someone smiling), our zygomatic major contracts ever so slightly–as yours almost surely is right now (Foroni & Semin, 2009). (By the way, the tendency to ape the facial expressions of our interaction partners is so natural that, yes, even apes do it; Davila Ross, Menzler, & Zimmermann, 2008.) Because facial expressions can cause the emotions they signify, mimicking another person’s facial expression allows us to feel what they are feeling and therefore identify their emotions.

What’s the evidence for this? First, people find it difficult to identify other people’s emotions when they are unable to make facial expressions of our own, for example, if their facial muscles are paralyzed with Botox (Niedenthal et al., 2005). People also find it difficult to identify other people’s emotions when they are unable to experience emotions of their own (Hussey & Safford, 2009; Pitcher et al., 2008). For example, people with amygdala damage don’t normally feel fear and anger, and are typically poor at recognizing the expressions of those emotions in others (Adolphs, Russell, & Tranel, 1999). On the flip side, people who are naturally quite good at figuring out what others are feeling tend to be natural mimics (Sonnby-

Deceptive Expression

Our emotional expressions can communicate our feelings truthfully–or not. When a friend makes a sarcastic remark about our haircut, we truthfully express our contempt with an arched brow and a reinforcing hand gesture; but when our boss makes the same remark, we swallow hard and fake a pained smile. Our knowledge that it is permissible to show contempt for a peer but not a superior is a display rule, which is a norm for the appropriate expression of emotion (Ekman, 1972; Ekman & Friesen, 1968). Obeying a display rule requires several techniques:

Intensification involves exaggerating the expression of one’s emotion, as when a person pretends to be more surprised by a gift than she really is.

Intensification involves exaggerating the expression of one’s emotion, as when a person pretends to be more surprised by a gift than she really is. Deintensification involves muting the expression of one’s emotion, as when the loser of a contest tries to look less distressed than he really is.

Deintensification involves muting the expression of one’s emotion, as when the loser of a contest tries to look less distressed than he really is. Masking involves expressing one emotion while feeling another, as when a poker player tries to look distressed rather than delighted as she examines a hand with four aces.

Masking involves expressing one emotion while feeling another, as when a poker player tries to look distressed rather than delighted as she examines a hand with four aces. Neutralizing involves feeling an emotion but displaying no expression, as when a judge tries not to betray his leanings while lawyers are making their arguments (see FIGURE 8.9).

Neutralizing involves feeling an emotion but displaying no expression, as when a judge tries not to betray his leanings while lawyers are making their arguments (see FIGURE 8.9).

How does emotional expression differ across cultures?

Although people in different cultures use many of the same techniques, they use them in the service of different display rules. For example, in one study, Japanese and American college students watched an unpleasant video of car accidents and amputations (Ekman, 1972; Friesen, 1972). When the students didn’t know that the experimenters were observing them, Japanese and American students made similar expressions of disgust, but when they realized that they were being observed, the Japanese students (but not the American students) masked their disgust with pleasant expressions. In many Asian countries it is considered rude to display negative emotions in the presence of a respected person, and so citizens of these countries tend to mask or neutralize their expressions. The fact that different cultures have different display rules may also help explain the fact that people are better at recognizing the facial expressions of people from their own cultures (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002).

327

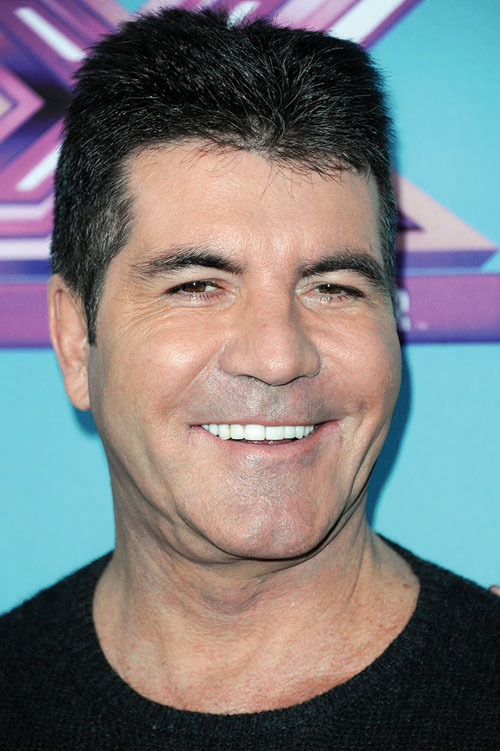

Figure 8.9: Neutralizing Can you tell what this man is feeling? He sure hopes not. Doyle Brunson is a champion poker player who knows how to keep a “poker face,” which is a neutral expression that provides little information about his emotional state.

Figure 8.9: Neutralizing Can you tell what this man is feeling? He sure hopes not. Doyle Brunson is a champion poker player who knows how to keep a “poker face,” which is a neutral expression that provides little information about his emotional state.

Our attempts to obey our culture’s display rules don’t always work out so well. Darwin (1899/2007) noted that “those muscles of the face which are least obedient to the will, will sometimes alone betray a slight and passing emotion” (p. 64). Anyone who has ever watched the loser of a beauty pageant congratulate the winner knows that voices, bodies, and faces are “leaky” instruments that often betray a person’s emotional state. Even when people smile bravely to mask their disappointment, for example, their faces tend to express small bursts of disappointment that last just 1/5 to 1/25 of a second (Porter & ten Brinke, 2008). These micro-

Morphology: Certain facial muscles tend to resist conscious control, and for a trained observer, these so-

Morphology: Certain facial muscles tend to resist conscious control, and for a trained observer, these so-called reliable muscles are quite revealing. For example, the zygomatic major raises the corners of the mouth, and this happens when people smile spontaneously or when they force themselves to smile. But only a genuine, spontaneous smile engages the obicularis oculi, which crinkles the corners of the eyes (see FIGURE 8.10).

Figure 8.10: Crinkle Eyes Can you tell which of the two finalists in the 1986 Miss America pageant just won? Check out their eyes. Only one woman is showing the telltale “corner crinkle” that signifies genuine happiness. The winner is on the right, but don’t feel too bad for the loser on the left. Her name is Halle Berry and she went on to have a pretty good acting career.

AP PHOTO/RAUL DEMOLINA

Figure 8.10: Crinkle Eyes Can you tell which of the two finalists in the 1986 Miss America pageant just won? Check out their eyes. Only one woman is showing the telltale “corner crinkle” that signifies genuine happiness. The winner is on the right, but don’t feel too bad for the loser on the left. Her name is Halle Berry and she went on to have a pretty good acting career.

AP PHOTO/RAUL DEMOLINA Symmetry: Sincere expressions are a bit more symmetrical than insincere expressions. A slightly lopsided smile is less likely to be genuine than is a perfectly even one.

Symmetry: Sincere expressions are a bit more symmetrical than insincere expressions. A slightly lopsided smile is less likely to be genuine than is a perfectly even one. Duration: Sincere expressions tend to last between a half second and 5 seconds, and expressions that last for shorter or longer periods are more likely to be insincere.

Duration: Sincere expressions tend to last between a half second and 5 seconds, and expressions that last for shorter or longer periods are more likely to be insincere. Temporal patterning: Sincere expressions appear and disappear smoothly over a few seconds, whereas insincere expressions tend to have more abrupt onsets and offsets.

Temporal patterning: Sincere expressions appear and disappear smoothly over a few seconds, whereas insincere expressions tend to have more abrupt onsets and offsets.

Our emotions don’t just leak on our faces: They leak all over the place. Research has shown that many aspects of our verbal and nonverbal behavior are altered when we tell a lie (DePaulo et al., 2003). For example, liars speak more slowly, take longer to respond to questions, and respond in less detail than do those who are telling the truth. Liars are also less fluent, less engaging, more uncertain, more tense, and less pleasant than truth-

328

What is the problem with lie-

Given the reliable differences between sincere and insincere expressions, you might think that people would be quite good at telling one from the other. In fact, studies show that people are dreadful at this, and under most circumstances perform barely better than chance (DePaulo, Stone, & Lassiter, 1985; Ekman, 1992; Zuckerman, DePaulo, & Rosenthal, 1981; Zuckerman & Driver, 1985). One reason for this is that people have a strong bias toward believing that others are sincere, which explains why people tend to mistake liars for truth-

When people can’t do something well (e.g., adding numbers or picking up 10-

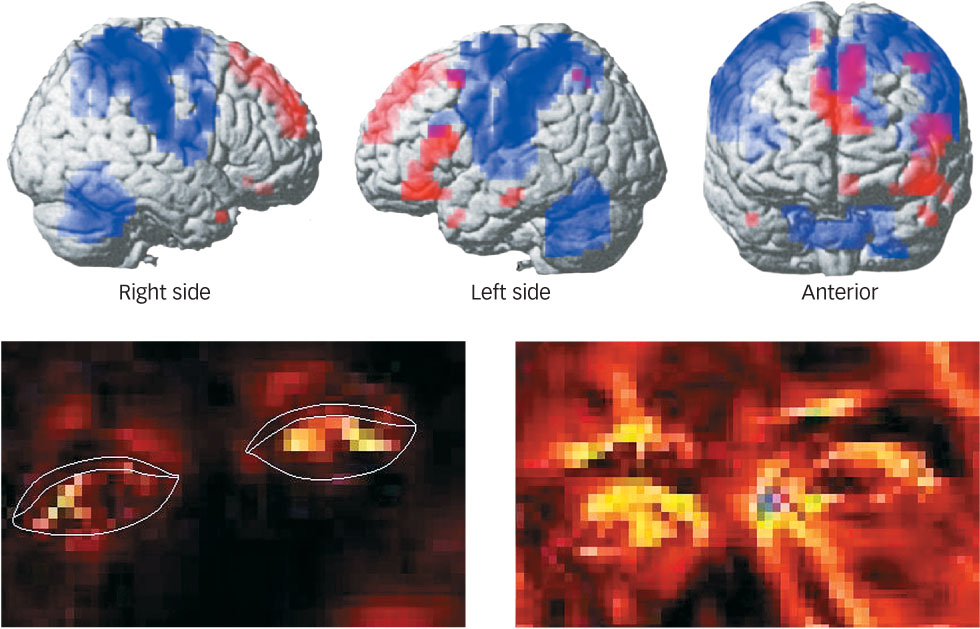

Figure 8.11: Lie Detection Machines Some researchers hope to replace the polygraph with accurate machines that measure changes in blood flow in the brain and the face. As the top panel shows, some areas of the brain are more active when people tell lies than when they tell the truth (shown in red), and some are more active when people tell the truth than when they tell lies (shown in blue; Langleben et al., 2005). The bottom panel shows images taken by a thermal camera that detects the heat caused by blood flow to different parts of the face. The images show a person’s face before (left) and after (right) telling a lie (Pavlidis, Eberhardt, & Levine, 2002). Although neither of these new techniques is extremely accurate, that could soon change.

Figure 8.11: Lie Detection Machines Some researchers hope to replace the polygraph with accurate machines that measure changes in blood flow in the brain and the face. As the top panel shows, some areas of the brain are more active when people tell lies than when they tell the truth (shown in red), and some are more active when people tell the truth than when they tell lies (shown in blue; Langleben et al., 2005). The bottom panel shows images taken by a thermal camera that detects the heat caused by blood flow to different parts of the face. The images show a person’s face before (left) and after (right) telling a lie (Pavlidis, Eberhardt, & Levine, 2002). Although neither of these new techniques is extremely accurate, that could soon change.

COURTESY OF IOANNIS PAVLIDIS

COURTESY OF IOANNIS PAVLIDIS. (PAVLIDIS, EBERHARDT, AND LEVINE, 2002. SEEING THROUGH THE FACE OF DECEPTION).

329

CULTURE & COMMUNITY: Is it what you say or how you say it?

We can learn a lot about people by paying attention both to what they say and to how they say it. But recent evidence (Ishii, Reyes, & Kitayama, 2003) suggests that some cultures place more emphasis on one of these than on the other.

Research participants heard a voice pronouncing pleasant or unpleasant words (such as pretty or complaint) in either a pleasant or an unpleasant tone of voice. On some trials, they were told to ignore the word and to classify the pleasantness of the voice; on other trials, they were told to ignore the voice and classify the pleasantness of the word.

Which of these kinds of information was more difficult to ignore? It depended on the participant’s nationality. American participants found it relatively easy to ignore the speaker’s tone of voice, but relatively difficult to ignore the pleasantness of the word being spoken. Japanese participants, on the other hand, found it relatively easy to ignore the pleasantness of the word, but relatively difficult to ignore the speaker’s tone of voice. It seems that, in America, what you say matters more than how you say it, but in Japan, just the opposite is true.

The voice, the body, and the face all communicate information about a person’s emotional state.

The voice, the body, and the face all communicate information about a person’s emotional state. Darwin suggested that these emotional expressions are the same for all people and are universally understood, and research suggests that this is generally true.

Darwin suggested that these emotional expressions are the same for all people and are universally understood, and research suggests that this is generally true. Emotions cause expressions, but expressions can also cause emotions.

Emotions cause expressions, but expressions can also cause emotions. Emotional mimicry allows people to experience and hence identify the emotions of others.

Emotional mimicry allows people to experience and hence identify the emotions of others. Not all emotional expressions are sincere because people use display rules to help them decide which emotions to express.

Not all emotional expressions are sincere because people use display rules to help them decide which emotions to express. Different cultures have different display rules, but people enact those rules using the same techniques.

Different cultures have different display rules, but people enact those rules using the same techniques. There are reliable differences between sincere and insincere emotional expressions and between truthful and untruthful utterances, but people are generally poor at determining when an expression is sincere or an utterance is truthful. The polygraph can distinguish true from false utterances with better-

There are reliable differences between sincere and insincere emotional expressions and between truthful and untruthful utterances, but people are generally poor at determining when an expression is sincere or an utterance is truthful. The polygraph can distinguish true from false utterances with better-than- chance accuracy, but its error rate is troublingly high.

330