5.1 Conscious and Unconscious: The Mind’s Eye, Open and Closed

What does it feel like to be you right now? It probably feels as though you are somewhere inside your head, looking out at the world through your eyes. You can feel your hands on this book, perhaps, and notice the position of your body or the sounds in the room when you orient yourself toward them. If you shut your eyes, you may be able to imagine things in your mind, even though all the while thoughts and feelings come and go, passing through your imagination. But where are “you,” really? And how is it that this theatre of consciousness gives you a view of some things in your world and your mind but not others? The theatre in your mind does not have seating for more than one, making it difficult to share what is on your mental screen with your friends, a researcher, or even yourself in precisely the same way a second time. We will look first at the difficulty of studying consciousness directly, examine the nature of consciousness (what it is that can be seen in this mental theatre), and then explore the unconscious mind (what is not visible to the mind’s eye).

5.1.1 The Mysteries of Consciousness

What are the great mysteries of consciousness?

Other sciences, such as physics, chemistry, and biology, have the great luxury of studying objects, things that we all can see. Psychology studies objects, too, looking at people and their brains and behaviours, but it has the unique challenge of also trying to make sense of subjects. Physicists are not concerned with what it is like to be a neutron, but psychologists hope to understand what it is like to be a human; that is, they seek to understand the subjective perspectives of the people whom they study. Psychologists hope to include an understanding of phenomenology how things seem to the conscious person, in their understanding of mind and behaviour. After all, consciousness is an extraordinary human property. But including phenomenology in psychology brings up mysteries pondered by great thinkers almost since the beginning of thinking. Let us look at two of the more vexing mysteries of consciousness: the problem of other minds and the mind–

5.1.1.1 The Problem of Other Minds

One great mystery is called the problem of other minds, the fundamental difficulty we have in perceiving the consciousness of others. How do you know that anyone else is conscious? They tell you that they are conscious, of course, and are often willing to describe in depth how they feel, how they think, what they are experiencing, and how good or how bad it all is. But perhaps they are just saying these things. There is no clear way to distinguish a conscious person from someone who might do and say all the same things as a conscious person but who is not conscious. Philosophers have called this hypothetical nonconscious person a zombie, in reference to the living-

Even the consciousness meter used by anesthesiologists falls short. It certainly does not give the anesthesiologist any special insight into what it is like to be the patient on the operating table; it only predicts whether patients will say they were conscious. We simply lack the ability to directly perceive the consciousness of others. In short, you are the only thing in the universe you will ever truly know what it is like to be.

The problem of other minds also means there is no way you can tell if another person’s experience of anything is at all like yours. Although you know what the colour red looks like to you, for instance, you cannot know whether it looks the same to other people. Maybe they are seeing what you see as blue and just calling it red in a consistent way. If their inner experience “looks” blue, but they say it looks hot and is the colour of a tomato, you will never be able to tell that their experience differs from yours. Of course, most people have come to trust each other in describing their inner lives, reaching the general assumption that other human minds are pretty much like their own. But they do not know this for a fact, and they cannot know it directly.

How do people perceive other minds?

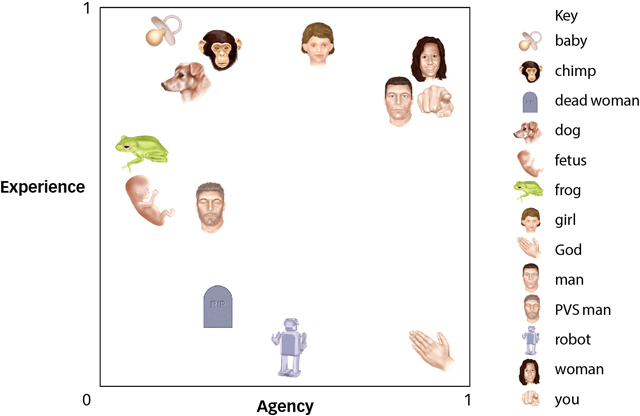

How do people perceive other minds? Researchers conducting a large online survey asked people to compare the minds of 13 different targets, such as a baby, a chimp, a robot, a man, and a woman, on 18 different mental capacities, such as feeling pain, pleasure, hunger, and consciousness (see FIGURE 5.1) (Gray, Gray, & Wegner, 2007). Respondents who were judging the mental capacity to feel pain, for example, compared pairs of targets: Is a frog or a dog more able to feel pain? Is a baby or a robot more able to feel pain? When the researchers examined all the comparisons on the different mental capacities with the computational technique of factor analysis (see the Intelligence chapter), they found that people judge minds according to two main capacities: the capacity for experience (such as the ability to feel pain, pleasure, hunger, consciousness, anger, or fear) and the capacity for agency (such as the ability for self-

Figure 5.1: Dimensions of Mind Perception When participants judged the mental capacities of 13 targets, two dimensions of mind perception were discovered (Gray et al., 2007). Participants perceived minds as varying in the capacity for experience (such as abilities to feel pain or pleasure) and in the capacity for agency (such as abilities to plan or exert self-

Figure 5.1: Dimensions of Mind Perception When participants judged the mental capacities of 13 targets, two dimensions of mind perception were discovered (Gray et al., 2007). Participants perceived minds as varying in the capacity for experience (such as abilities to feel pain or pleasure) and in the capacity for agency (such as abilities to plan or exert self-How does the capacity for experience differ from the capacity for agency?

Ultimately, the problem of other minds is a problem for psychological science. As you will remember from the Methods chapter, the scientific method requires that any observation made by one scientist should, in principle, be available for observation by any other scientist. But if other minds are not observable, how can consciousness be a topic of scientific study? One radical solution is to eliminate consciousness from psychology entirely and follow the other sciences into total objectivity by renouncing the study of anything mental. This was the solution offered by behaviourism, and it turned out to have its own shortcomings, as you saw in the Psychology: Evolution of a Science chapter. Despite the problem of other minds, modern psychology has embraced the study of consciousness. The astonishing richness of mental life simply cannot be ignored.

5.1.1.2 The Mind–Body Problem

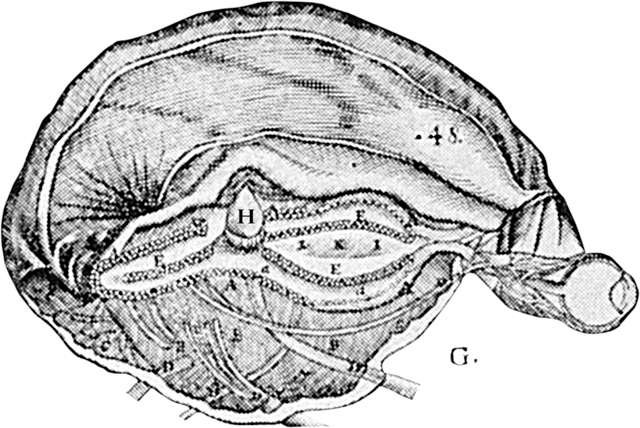

Figure 5.2: Seat of the Soul Descartes imagined that the seat of the soul—

Figure 5.2: Seat of the Soul Descartes imagined that the seat of the soul—Another mystery of consciousness is the mind-body problem, the issue of how the mind is related to the brain and body. French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes (1596–

But Descartes was right in pointing out the difficulty of reconciling the physical body with the mind. Most psychologists assume that mental events are intimately tied to brain events, such that every thought, perception, or feeling is associated with a particular pattern of activation of neurons in the brain (see the Neuroscience and Behaviour chapter). Thinking about a particular person, for instance, occurs with a unique array of neural connections and activations. If the neurons repeat that pattern, then you must be thinking of the same person; conversely, if you think of the person, the brain activity occurs in that pattern.

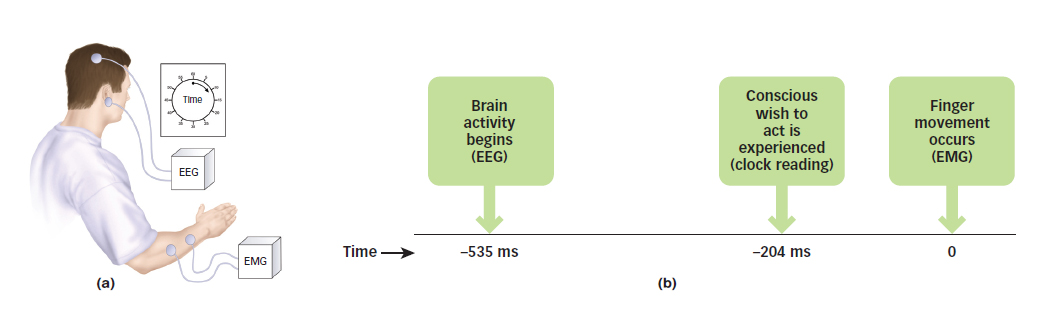

One telling set of studies, however, suggests that the brain’s activities precede the activities of the conscious mind. The electrical activity in the brains of volunteers was measured using sensors placed on their scalps as they repeatedly decided when to move a hand (Libet, 1985). Participants were also asked to indicate exactly when they consciously chose to move by reporting the position of a dot moving rapidly around the face of a clock just at the point of the decision (FIGURE 5.3a). As a rule, the brain begins to show electrical activity around half a second before a voluntary action (535 milliseconds [ms], to be exact). This makes sense because brain activity certainly seems to be necessary to get an action started.

Figure 5.3: The Timing of Conscious Will (a) In Benjamin Libet’s experiments, the participant was asked to move fingers at will while watching a dot move around the face of a clock to mark the moment at which the action was consciously willed. Meanwhile, EEG sensors timed the onset of brain activation and EMG sensors timed the muscle movement. (b) The experiment showed that brain activity (EEG) precedes the willed movement of the finger (EMG), but that the reported time of consciously willing the finger to move follows the brain activity.

Figure 5.3: The Timing of Conscious Will (a) In Benjamin Libet’s experiments, the participant was asked to move fingers at will while watching a dot move around the face of a clock to mark the moment at which the action was consciously willed. Meanwhile, EEG sensors timed the onset of brain activation and EMG sensors timed the muscle movement. (b) The experiment showed that brain activity (EEG) precedes the willed movement of the finger (EMG), but that the reported time of consciously willing the finger to move follows the brain activity.

What comes first: brain activity or thinking?

What this experiment revealed, though, was that the brain also started to show electrical activity before the person’s conscious decision to move. As shown in FIGURE 5.3b, these studies found that the brain becomes active more than 300 ms before participants report that they are consciously trying to move. The feeling that you are consciously willing your actions, it seems, may be a result rather than a cause of your brain activity. Although your personal intuition is that you think of an action and then do it, these experiments suggest that your brain is getting started before either the thinking or the doing, preparing the way for both thought and action. Quite simply, it may appear to us that our minds are leading our brains and bodies, but the order of events may be the other way around (Haggard & Tsakiris, 2009; Wegner, 2002).

Consciousness has its mysteries, but psychologists like a challenge. Although researchers may not be able to know exactly how consciousness arises from the brain, this does not prevent them from collecting people’s reports of conscious experiences and learning how these reports reveal the nature of consciousness.

5.1.2 The Nature of Consciousness

How would you describe your own consciousness? Researchers examining people’s descriptions suggest that consciousness has four basic properties (intentionality, unity, selectivity, and transience), that it occurs on different levels, and that it includes a range of different contents. Let us examine each of these points in turn.

5.1.2.1 Four Basic Properties

The first property of consciousness is intentionality, the quality of being directed toward an object. Consciousness is always about something. Psychologists have tried to measure the relationship between consciousness and its objects, examining the size and duration of the relationship. How long can consciousness be directed toward an object, and how many objects can it take on at one time? Researchers have found that conscious attention is limited. Despite all the lush detail you see in your mind’s eye, the kaleidoscope of sights and sounds and feelings and thoughts, the object of your consciousness at any one moment is just a small part of all of this (see FIGURE 5.4). To describe how this limitation works, psychologists refer to three other properties of consciousness: unity, selectivity, and transience.

Figure 5.4: Bellotto’s Dresden and Closeup (left) You may think the people on the bridge in the distance (in the red outline) seem finely detailed in View of Dresden with the Frauenkirche at Left by Bernardo Bellotto (1720–

Figure 5.4: Bellotto’s Dresden and Closeup (left) You may think the people on the bridge in the distance (in the red outline) seem finely detailed in View of Dresden with the Frauenkirche at Left by Bernardo Bellotto (1720–The second basic property of consciousness is unity, which is the ability to integrate information from all of the body’s senses into one coherent whole. As you read this book, your five senses are taking in a great deal of information. Your eyes are scanning lots of black squiggles on a page (or screen) while also sensing an enormous array of shapes, colours, depths, and textures in your periphery; your hands are gripping a heavy book (or computer); your butt and feet may sense pressure from gravity pulling you against a chair or floor; and you may be listening to music or talking in another room, while smelling the odour of freshly made popcorn (or your roommate’s dirty laundry). Although your body is constantly sensing an enormous amount of information from the world around you, your brain—

The third property of consciousness is selectivity, the capacity to include some objects but not others. While binding the many sensations around you into a coherent whole, your mind must make decisions about which pieces of information to include, and which to exclude. Inattentional blindness, which you learned about in the Sensation and Perception chapter, is an example of selectivity. Selectivity is also shown through studies of dichotic listening, in which people wearing headphones hear different messages in each ear. Research participants were instructed to repeat aloud the words they heard in one ear while a different message was presented to the other ear (Cherry, 1953). As a result of focusing on the words they were supposed to repeat, participants noticed little of the second message, often not even realizing that at some point it changed from English to German! So, consciousness filters out some information. At the same time, participants did notice when the voice in the unattended ear changed from a man’s to a woman’s. Participants in another study were especially likely to notice if their own name was spoken into the unattended ear (Moray, 1959). This suggests that the selectivity of consciousness can also work to tune in other information. Perhaps you, too, have noticed how abruptly your attention is diverted from whatever conversation you are having when someone else within earshot at a party mentions your name. Selectivity is not only a property of waking consciousness: the mind works this way in other states. People are more sensitive to their own name than others’ names, for example, even during sleep (Oswald, Taylor, & Triesman, 1960). This is why, when you are trying to wake someone, it is best to say the person’s name.

How does your mind know which information to allow into consciousness, and which to filter out?

The fourth and final basic property of consciousness is transience, or the tendency to change. Consciousness wiggles and fidgets like a toddler in the seat behind you on an airplane. The mind wanders not just sometimes, but incessantly, from one “right now” to the next “right now” and then on to the next (Wegner, 1997). William James, whom you met way back in the Psychology: Evolution of a Science chapter, famously described consciousness as a stream: “Consciousness … does not appear to itself chopped up in bits. Such words as ‘chain’ or ‘train’ do not describe it. … It is nothing jointed; it flows. A ‘river’ or a ‘stream’ are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described” (James, 1890, Vol. 1, p. 239). Books written in the “stream of consciousness” style, such as James Joyce’s Ulysses, illustrate the whirling, chaotic, and constantly changing flow of consciousness. Here is an excerpt with Molly Bloom speaking:

I wished I could have picked every morsel of that chicken out of my fingers it was so tasty and browned and as tender as anything only for I did not want to eat everything on my plate those forks and fishslicers were hallmarked silver too I wish I had some I could easily have slipped a couple into my muff when I was playing with them then always hanging out of them for money in a restaurant for the bit you put down your throat we have to be thankful for our mangy cup of tea itself as a great compliment to be noticed the way the world is divided in any case if its going to go on I want at least two other good chemises for one thing and but I do not know what kind of drawers he likes none at all I think did not he say yes and half the girls in Gibraltar never wore them either naked as God made them that Andalusian singing her Manola she did not make much secret of what she hadnt yes and the second pair of silkette stockings is laddered after one days wear I could have brought them back to Lewers this morning and kicked up a row and made that one change them only not to upset myself and run the risk of walking into him and ruining the whole thing and one of those kidfitting corsets Id want advertised cheap in the Gentlewoman with elastic gores on the hips he saved the one I have but thats no good what did they say they give a delightful figure line 11/6 obviating that unsightly broad appearance across the lower back to reduce flesh my belly is a bit too big Ill have to knock off the stout at dinner or am I getting too fond of it… (1922/2013, p. 625).

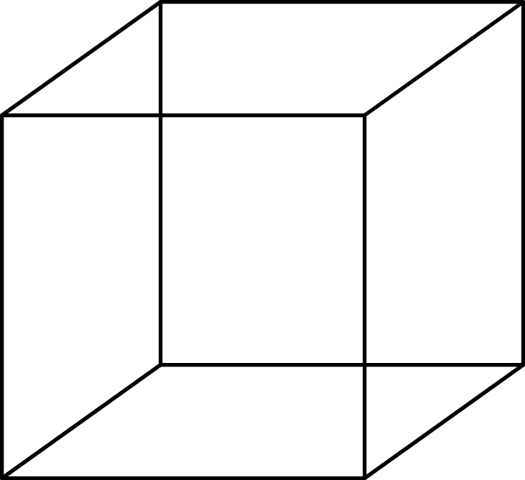

The stream of consciousness may flow in this way partly because of the limited capacity of the conscious mind. We humans can hold only so much information in mind, after all, so when more information is selected, some of what is currently there must disappear. As a result, our focus of attention keeps changing. The stream of consciousness flows so inevitably that it even changes our perspective when we view a constant object like a Necker cube (see FIGURE 5.5).

Figure 5.5: The Necker Cube This cube has the property of reversible perspective in that you can bring one or the other of its two square faces to the front in your mind’s eye. Although it may take a while to reverse the figure at first, once people have learned to do it, they can reverse it regularly, about once every 3 s (Gomez et al., 1995). The stream of consciousness flows even when the target is a constant object.

Figure 5.5: The Necker Cube This cube has the property of reversible perspective in that you can bring one or the other of its two square faces to the front in your mind’s eye. Although it may take a while to reverse the figure at first, once people have learned to do it, they can reverse it regularly, about once every 3 s (Gomez et al., 1995). The stream of consciousness flows even when the target is a constant object.

5.1.2.2 Levels of Consciousness

Consciousness can also be understood as having levels, ranging from minimal consciousness to full consciousness to self-

In its minimal form, consciousness is just a connection between the person and the world. When you sense the sun coming in through the window, for example, you might turn toward the light. Such minimal consciousness is a low-

What factor of full consciousness distinguishes it from minimal consciousness?

Human consciousness is often more than minimal, of course, but what exactly gets added? Consider the glorious feeling of waking up on a spring morning as rays of sun stream across your pillow. It is not just that you are having this experience: Being fully conscious means that you are also aware that you are having this experience. The critical ingredient that accompanies full consciousness is that you know and are able to report your mental state. That is a subtle distinction: Being fully conscious means that you are aware of having a mental state while you are experiencing the mental state itself. When you have a hurt leg and mindlessly rub it, for instance, your pain may be minimally conscious. After all, you seem to be experiencing pain because you have acted and are indeed rubbing your leg. It is only when you realize that it hurts, though, that the pain becomes fully conscious. Have you ever been driving a car and suddenly realized that you do not remember the past 15 minutes of driving? Chances are that you were not unconscious, but instead minimally conscious. When you are completely aware and thinking about your driving, you have moved into the realm of full consciousness. Full consciousness involves not only thinking about things but also thinking about the fact that you are thinking about things (Jaynes, 1976).

Full consciousness involves a certain consciousness of oneself; the person notices the self in a particular mental state (“Here I am, reading this sentence.”). However, this is not quite the same thing as self-consciousness. Sometimes consciousness is entirely flooded with the self (“Not only am I reading this sentence, but I have a blemish on the end of my nose today that makes me feel like guiding a sleigh.”). Self-

When do people go out of their way to avoid mirrors?

Self-

HOT SCIENCE: Disorders of Consciousness

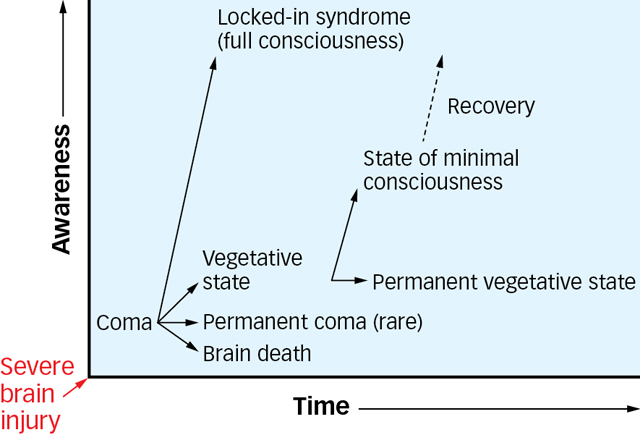

Improvements in medical intensive care in the last several years means that more patients are surviving severe brain injury caused by an illness or accident. Such brain damage can produce a transient or permanent disorder of consciousness, in which the patient is not able to demonstrate either full consciousness or self-

Patients in a coma look a bit like they are asleep—

Patients in a vegetative state alternate between eyes-

Patients in a minimally consciousness state can respond reliably but somewhat inconsistently to sensory stimulation. Again this condition can be temporary, preceding recovery of full awareness, or may be permanent.

Locked-

|

Disorders of Consciousness |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Diagnosis |

Arousal/wakefulness |

Awareness |

Communication |

|

Coma |

Do not open eyes No sleep- |

No evidence |

None |

|

Vegetative state |

Open eyes |

No evidence |

None |

|

Minimally conscious state |

Open eyes |

Inconsistent but reproducible evidence |

Ranges from none to inconsistent, but reproducible |

|

Locked- |

Open eyes |

Fully aware |

Consistent, using vertical eye movement |

|

Reprinted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Owen, A. M., & Coleman, M. R. (2008). Functional neuroimaging of the vegetative state. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9, 235– |

|||

Coma, vegetative state, and minimally conscious state are all disorders of consciousness that occur after severe brain injury. Locked-

Coma, vegetative state, and minimally conscious state are all disorders of consciousness that occur after severe brain injury. Locked-How do doctors determine whether a patient is aware? Traditionally, they observe the patient’s behaviour and judge whether the patient is repeatedly able to respond to commands (like “raise your left arm”), or to the sound of his or her name being spoken. However, brain damage can also make it difficult for patients to move their muscles voluntarily in order to produce a behaviour that the doctor can see or hear. In recent years, brain-

Most animals cannot follow this path to civilization. The typical dog, cat, or bird seems mystified by a mirror, ignoring it or acting as though there is some other critter back there. However, chimpanzees that have spent time with mirrors sometimes behave in ways that suggest they recognize themselves in a mirror. To examine this, researchers painted an odourless red dye over the eyebrow of an anesthetized chimp and then watched when the awakened chimp was presented with a mirror (Gallup, 1977). If the chimp interpreted the mirror image as a representation of some other chimp with an unusual approach to cosmetics, we would expect it just to look at the mirror or perhaps to reach toward it. But the chimp reached toward its own eye as it looked into the mirror—

Versions of this experiment have now been repeated with many different animals, and it turns out that, like humans, animals such as chimpanzees and orangutans (Gallup, 1997), possibly dolphins (Reiss & Marino, 2001), and maybe even elephants (Plotnik, de Waal, & Reiss, 2006) and magpies (Prior, Schwartz, & Güntürkün, 2008) recognize their own mirror images. Dogs, cats, crows, monkeys, and gorillas have been tested, too, but do not seem to know they are looking at themselves. Even humans do not have self-

5.1.2.3 Conscious Contents

What is on your mind? For that matter, what is on everybody’s mind? One way to learn what is on people’s minds is to ask them, and much research has called on people simply to think aloud. A more systematic approach is the experience-

Experience-

|

Current Concern Category |

Example |

Frequency of Students Who Mentioned the Concern |

|---|---|---|

|

Family |

Gain better relations with immediate family |

40% |

|

Roommate |

Change attitude or behaviour of roommate |

29% |

|

Household |

Clean room |

52% |

|

Friends |

Make new friends |

42% |

|

Dating |

Desire to date a certain person |

24% |

|

Sexual intimacy |

Abstaining from sex |

16% |

|

Health |

Diet and exercise |

85% |

|

Employment |

Get a summer job |

33% |

|

Education |

Go to graduate school |

43% |

|

Social activities |

Gain acceptance into a campus organization |

34% |

|

Religious |

Attend church more |

51% |

|

Financial |

Pay rent or bills |

8% |

|

Government |

Change government policy |

14% |

|

Source: Goetzman, E. S., Hughes, T., & Klinger, E. (1994). Current concerns of college students in a midwestern sample. University of Minnesota, Morris. |

||

How do researchers study subjective experience?

Think for a moment about your own current concerns. What topics have been on your mind the most in the past day or two? Your mental “to do” list may include things you want to get, keep, avoid, work on, remember, and so on (Little, 1993). Items on the list often pop into mind, sometimes even with an emotional punch (“The test in this class is tomorrow!”). People in one study had their skin conductance level (SCL) measured to assess their emotional responses (Nikula, Klinger, & Larson-

We discussed thinking about our current concerns before, but what is our subjective experience when actually carrying out the events of our daily lives? We are, of course, each engaged in our daily lives, but rarely examine what our moment-

|

|

Mean Affect Rating |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Activities |

Positive Affect |

Mean Hours/Day |

|

Intimate relations |

5.1 |

0.2 |

|

Socializing |

4.59 |

2.3 |

|

Relaxing |

4.42 |

2.2 |

|

Pray/worship/meditate |

4.35 |

0.4 |

|

Eating |

4.34 |

2.2 |

|

Exercising |

4.31 |

0.2 |

|

Watching TV |

4.19 |

2.2 |

|

Shopping |

3.95 |

0.4 |

|

Preparing food |

3.93 |

1.1 |

|

On the phone |

3.92 |

2.5 |

|

Napping |

3.87 |

0.9 |

|

Taking care of my children |

3.86 |

1.1 |

|

Computer/e- |

3.81 |

1.9 |

|

Housework |

3.73 |

1.1 |

|

Working |

3.62 |

6.9 |

|

Commuting |

3.45 |

1.6 |

|

Source: Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwartz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method (Table 1). Science, 306, 1776– |

||

5.1.2.3.1 Daydreaming.

Figure 5.6: The Default Network Activated during Daydreaming An fMRI scan shows that many areas, known as the default network, are active when the person is not given a specific mental task to perform during the scan (Mason et al., 2007).

Figure 5.6: The Default Network Activated during Daydreaming An fMRI scan shows that many areas, known as the default network, are active when the person is not given a specific mental task to perform during the scan (Mason et al., 2007).

What part of the brain is active during daydreaming?

Current concerns do not seem all that concerning, however, during daydreaming, a state of consciousness in which a seemingly purposeless flow of thoughts comes to mind. When thoughts drift along this way, it may seem as if you are just wasting time. The brain, however, is active even when there is no specific task at hand. This mental work done in daydreaming was examined in an fMRI study of people resting in the scanner (Mason et al., 2007). Usually, people in brain scanning studies do not have time to daydream much because they are kept busy with mental tasks—

5.1.2.3.2 Thought Suppression.

The current concerns that populate consciousness can sometimes get the upper hand, transforming daydreams or everyday thoughts into rumination and worry. Thoughts that return again and again, or problem-

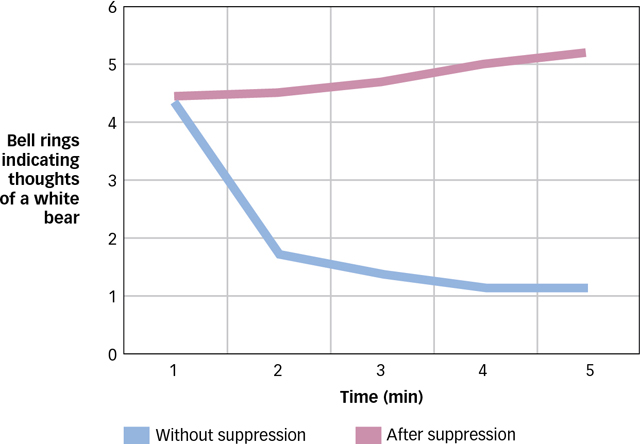

Or does it? The great Russian novelist, Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1863/1988, p. 49), remarked on the difficulty of thought suppression: “Try to pose for yourself this task: not to think of a polar bear, and you will see that the cursed thing will come to mind every minute.” Inspired by this observation, Daniel Wegner and his colleagues (1987) gave people this exact task in the laboratory. Participants were asked to try not to think about a white bear for 5 minutes while they recorded all their thoughts aloud into a tape recorder. In addition, they were asked to ring a bell if the thought of a white bear came to mind. On average, they mentioned the white bear or rang the bell (indicating the thought) more than once per minute. Thought suppression simply did not work and instead produced a flurry of returns of the unwanted thought. What is more, when some research participants later were specifically asked to change tasks and deliberately think about a white bear, they became oddly preoccupied with it. A graph of their bell rings in FIGURE 5.7 shows that these participants had the white bear come to mind far more often than did people who had only been asked to think about the bear from the outset, with no prior suppression. This rebound effect of thought suppression, the tendency of a thought to return to consciousness with greater frequency following suppression, suggests that attempts at mental control may be difficult indeed. The act of trying to suppress a thought may itself cause that thought to return to consciousness in a robust way.

5.1.2.3.3 The Ironic Monitor.

Figure 5.7: Rebound Effect Research participants were first asked to try not to think about a white bear, and then they were asked to think about it and to ring a bell whenever it came to mind. Compared to those who were simply asked to think about a bear without prior suppression, those people who first suppressed the thought showed a rebound of increased thinking (Wegner et al., 1987)

Figure 5.7: Rebound Effect Research participants were first asked to try not to think about a white bear, and then they were asked to think about it and to ring a bell whenever it came to mind. Compared to those who were simply asked to think about a bear without prior suppression, those people who first suppressed the thought showed a rebound of increased thinking (Wegner et al., 1987)

Similar to thought suppression, other attempts to steer consciousness in any direction can result in mental states that are precisely the opposite of those desired. How ironic: Trying to consciously achieve one task may produce precisely the opposite outcome! These ironic effects seem most likely to occur when the person is distracted or under stress. People who are distracted while they are trying to get into a good mood, for example, tend to become sad (Wegner, Erber, & Zanakos, 1993), and those who are distracted while trying to relax actually become more anxious than those who are not trying to relax (Wegner, Broome, & Blumberg, 1997). Likewise, an attempt not to overshoot a golf putt, undertaken during distraction, often yields the unwanted overshot (Wegner, Ansfield, & Pilloff, 1998). The theory of ironic processes of mental control proposes that such ironic errors occur because the mental process that monitors errors can itself produce them (Wegner, 1994a, 2009). In the attempt not to think of a white bear, for instance, a small part of the mind is ironically searching for the white bear.

Is consciously avoiding a worrisome thought a sensible strategy?

This ironic monitoring process is not present in consciousness. After all, trying not to think of something would be useless if monitoring the progress of suppression required keeping that target in consciousness. For example, if trying not to think of a white bear meant that you consciously kept repeating to yourself, “No white bear! No white bear!” then you have failed before you have begun: That thought is present in consciousness even as you strive to eliminate it. Rather, the ironic monitor is a process of the mind that works outside of consciousness, making us sensitive to all the things we do not want to think, feel, or do so that we can notice and consciously take steps to regain control if these things come back to mind. As this unconscious monitoring whirs along in the background, it unfortunately increases the person’s sensitivity to the very thought that is unwanted. Ironic processes are mental functions that are needed for effective mental control—

5.1.3 The Unconscious Mind

Many mental processes are unconscious, in the sense that they occur without our experience of them. When we speak, for instance, “We are not really conscious either of the search for words, or of putting the words together into phrases, or of putting the phrases into sentences. … The actual process of thinking … is not conscious at all … only its preparation, its materials, and its end result are consciously perceived” (Jaynes, 1976, p. 41). Just to put the role of consciousness in perspective, think for a moment about the mental processes involved in simple addition. What happens in consciousness between hearing a problem (what is four plus five?) and thinking of the answer (nine)? Probably nothing—

In the early part of the twentieth century, when structuralist psychologists, such as Edward Titchener, believed that introspection was the best method of research (see the Psychology: Evolution of a Science chapter), research volunteers trained in describing their thoughts tried to discern what happens when a simple problem brings to mind a simple answer (e.g., Watt, 1905). They drew the same blank you probably did. Nothing conscious seems to bridge this gap, but the answer comes from somewhere, and this emptiness points to the unconscious mind. To explore these hidden recesses, we can look at the classical theory of the unconscious introduced by Sigmund Freud and then at the modern cognitive psychology of unconscious mental processes.

5.1.3.1 Freudian Unconscious

The true champion of the unconscious mind was Sigmund Freud. As you read in the Psychology: Evolution of a Science chapter, Freud’s psychoanalytic theory viewed conscious thought as the surface of a much deeper mind made up of unconscious processes. Far more than just a collection of hidden processes, Freud described a dynamic unconscious—an active system encompassing a lifetime of hidden memories, the person’s deepest instincts and desires, and the person’s inner struggle to control these forces. The dynamic unconscious might contain hidden sexual thoughts about one’s parents, for example, or destructive urges aimed at a helpless infant—

Freud looked for evidence of the unconscious mind in speech errors and lapses of consciousness, or what are commonly called Freudian slips. Forgetting the name of someone you dislike, for example, is a slip that seems to have special meaning. Freud believed that errors are not random and instead have some surplus meaning that may appear to have been created by an intelligent unconscious mind, even though the person consciously disavows them. For example, when reporting on the news that members of the United States military had killed Osama bin Laden, several reporters and commentators at Fox News, a conservative American news outlet, independently reported that Obama bin Laden was dead. This slip even appeared as a printed announcement on one of its news shows.

What do Freudian slips tell us about the unconscious mind?

Did the Fox News slip mean anything? One experiment revealed that slips of speech can indeed be prompted by a person’s pressing concerns (Motley & Baars, 1979). Research participants in one group were told they might receive minor electric shocks, whereas those in another group heard no mention of this. Each person was then asked to read quickly through a series of word pairs, including shad bock. Those in the group warned about shock more often slipped in pronouncing this pair, blurting out bad shock.

Unlike errors created in experiments such as this one, many of the meaningful errors Freud attributed to the dynamic unconscious were not predicted in advance and so seem to depend on clever after-

5.1.3.2 A Modern View of the Cognitive Unconscious

Modern psychologists share Freud’s interest in the impact of unconscious mental processes on consciousness and on behaviour. However, rather than Freud’s vision of the unconscious as a teeming menagerie of animal urges and repressed thoughts, the current study of the unconscious mind views it as the factory that builds the products of conscious thought and behaviour (Kihlstrom, 1987; Wilson, 2002). The cognitive unconscious includes all the mental processes that give rise to a person’s thoughts, choices, emotions, and behaviour even though they are not experienced by the person.

One indication of the cognitive unconscious at work is when a person’s thoughts or behaviours are changed by exposure to information outside of consciousness. This happens in subliminal perception, when thought or behaviour is influenced by stimuli that a person cannot consciously report perceiving. Worries about the potential of subliminal influence were first provoked in 1957, when a marketer, James Vicary, claimed he had increased concession sales at a New Jersey theatre by flashing the words “Eat Popcorn” and “Drink Coke” briefly on-

Although the story above was a hoax, factors outside our conscious awareness can indeed influence our behaviour. For example, one classic study reported that exposure to information about getting old can make a person walk more slowly. John Bargh and his colleagues had undergraduate students complete a survey that called for them to make sentences with various words (1996). The students were not informed that most of the words were commonly associated with aging (Florida, grey, wrinkled), and even afterward they did not report being aware of this trend. In this case, the “aging” idea was not presented subliminally, just not very noticeably. As these research participants left the experiment, they were clocked as they walked down the hall. Compared with those not exposed to the aging-

The unconscious mind can be a kind of “mental butler,” taking over background tasks that are too tedious, subtle, or bothersome for consciousness to trifle with (Bargh & Chartrand, 1999; Bargh & Morsella, 2008; Bower, 1999). Psychologists have long debated just how smart this mental butler might be. Freud attributed great intelligence to the unconscious, believing that it harbours complex motives and inner conflicts and that it expresses these in an astonishing array of thoughts and emotions, as well as psychological disorders (see the Psychological Disorders chapter). Contemporary cognitive psychologists wonder whether the unconscious is so smart, however, and point out that some unconscious processes even seem downright “dumb” (Loftus & Klinger, 1992). For example, the unconscious processes that underlie the perception of subliminal visual stimuli do not seem able to understand the combined meaning of word pairs, although they can understand single words. To the conscious mind, for example, a word pair such as enemy loses is somewhat positive—

What evidence shows the unconscious mind is a good decision maker?

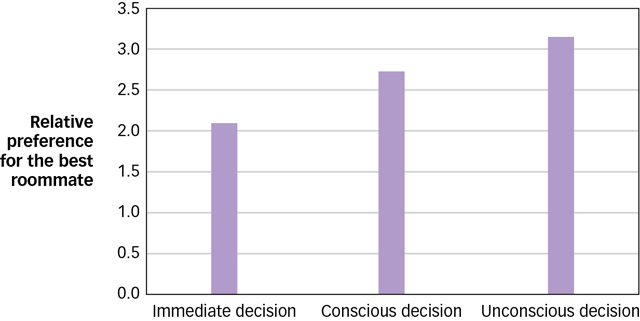

In some cases, however, the unconscious mind can make better decisions than the conscious mind. Participants in an experiment were asked to choose which of three hypothetical people with many different qualities they would prefer to have as a roommate (Dijksterhuis, 2004). One candidate was objectively better, with more positive qualities, and participants who were given 4 minutes to make a conscious decision tended to choose that one. A second group was asked for an immediate decision as soon as the information display was over, and a third group was encouraged to reach an unconscious decision. This group was also given 4 minutes after the display ended to give their answer (as the conscious group had been given), but during this interval their conscious minds were occupied with solving a set of anagrams. As you can see in FIGURE 5.8, the unconscious decision group showed a stronger preference for the good roommate than did the immediate decision or conscious decision groups. Unconscious minds seemed better able than conscious minds to sort out the complex information and arrive at the best choice. You can sometimes end up more satisfied with decisions you make going with your gut than with the decisions you consciously agonize over.

Figure 5.8: Decisions People making roommate decisions who had some time for unconscious deliberation chose better roommates than those who thought about the choice consciously or those who made snap decisions (Dijksterhuis, 2004).

Figure 5.8: Decisions People making roommate decisions who had some time for unconscious deliberation chose better roommates than those who thought about the choice consciously or those who made snap decisions (Dijksterhuis, 2004).

THE REAL WORLD: Anyone for Tennis?

In 1999, Scott Routley was seriously injured in a car accident when he pulled out in front of a Sarnia police cruiser. For 12 years he was considered by doctors to be in a vegetative state: showing periods of apparent eyes-

39-

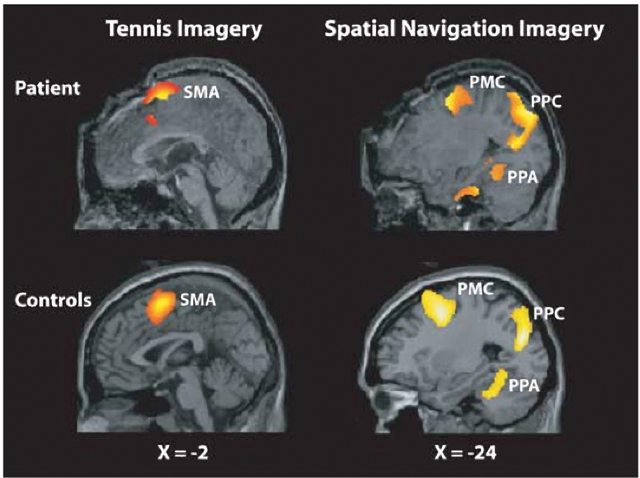

39-For many years, Adrian Owen and his colleagues at the University of Western Ontario, working with researchers in Cambridge, UK, and in Liège, Belgium, have been evaluating whether, and how, fMRI can be used to detect signs of consciousness in brain-

This image shows the distinct patterns of activity in a healthy control and in a brain-

This image shows the distinct patterns of activity in a healthy control and in a brain-When the researchers used this fMRI method with Scott, he was able to reliably generate the tennis and spatial-

Consciousness is a mystery of psychology because other people’s minds cannot be perceived directly and because the relationship between mind and body is perplexing.

Consciousness has four basic properties: intentionality, unity, selectivity, and transience. It can also be understood in terms of levels: minimal consciousness, full consciousness, and self-

consciousness. Conscious contents can include current concerns, daydreams, and unwanted thoughts.

Unconscious processes are sometimes understood as expressions of the Freudian dynamic unconscious, but they are more commonly viewed as processes of the cognitive unconscious that create our conscious thought and behaviour.

The cognitive unconscious is at work when subliminal perception and unconscious decision processes influence thought or behaviour without the person’s awareness.