3.0 Chapter Introduction

3

Neuroscience and Behaviour

IN THE SUMMER OF 2011, THREE National Hockey League players died within a few months of each other. Wade Belak, the oldest of the three, was born in Saskatoon in 1976. He was drafted into the NHL when he was 17 and played for six teams over his career, including the Quebec Nordiques and the Toronto Maple Leafs. He died accidentally (the police treated it as a suicide) in a Toronto apartment, leaving behind a wife and two young daughters. He was 35. Derek Boogaard, another native of Saskatchewan and the son of a Mountie, played for the Minnesota Wild and the New York Rangers. He was 28 years old when he died of a drug overdose, having mixed powerful painkillers and alcohol on a night out with friends. Rick Rypien, from Blairmore, Alberta, was the youngest of the three. He spent some time with the Regina major junior team and then with a minor professional team in Manitoba. When he was 22, he joined the Vancouver Canucks and played six seasons with them. He took his own life in his home in Crowsnest Pass, Alberta—

What did these three young men have in common, besides their passion for hockey? They were all “enforcers,” players who are expected to use aggressive methods such as fighting and checking, to respond to violence against their team members, especially star players and goalies. They had all suffered blows to the head and concussions in their hockey careers. Both Rypien and Belak suffered from clinical depression and Boogaard battled an addiction to painkillers, as well as depression.

Postmortem analysis of Boogaard’s brain revealed the presence of a condition known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a form of progressive brain damage that has been linked to repeated concussions (McKee et al., 2012). Although their brains were not examined, CTE is strongly suspected to have played a role in the deaths of Belak and Rypien as well, and is a confirmed diagnosis in three other deceased professional hockey players. CTE has been confirmed in the brains of over 20 professional football players, and has also been observed after repeated head injuries in boxing, wrestling, and rugby (Costanza et al., 2011; Daneshvar et al., 2011; Lahkan & Kirchgessner, 2012; McKee et al., 2012).

CTE is associated with an array of cognitive and emotional deficits in afflicted individuals, including inability to concentrate, memory loss, irritability, and depression, usually beginning within a decade after repeated concussions and worsening with time (McKee et al., 2009). CTE is not confined to aging or retired athletes. A recent study found evidence of CTE in a 17-

The symptoms of CTE, and the havoc they can wreak in the lives of affected individuals and their families, are stark reminders that our psychological, emotional, and social well-

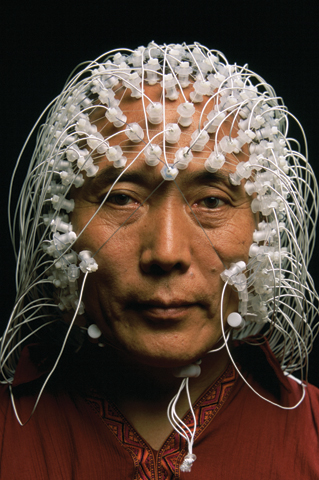

IN THIS CHAPTER, WE WILL CONSIDER HOW THE BRAIN WORKS, what happens when it does not, and how both states of affairs determine behaviour. First, we will introduce you to the basic unit of information processing in the brain, the neuron. The electrical and chemical activities of neurons are the starting point of all behaviour, thought, and emotion. Next, we will consider the anatomy of the central nervous system, focusing especially on the brain, including its overall organization, key structures that perform different functions, and its evolutionary development. Finally, we will discuss methods that allow us to study the brain and clarify our understanding of how it works. These include methods that examine the damaged brain and methods for scanning the living and healthy brain.