9.2 Language Development and the Brain

As the brain matures, specialization of specific neurological structures takes place, and this allows language to develop (Kuhl, 2010; Kuhl & Rivera-

9.2.1 Broca’s Area and Wernicke’s Area of the Brain

How does language processing change in the brain as the child matures?

In early infancy, language processing is distributed across many areas of the brain. But language processing gradually becomes more and more concentrated in two areas, Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, sometimes referred to as the language centres of the brain. As the brain matures, these areas become increasingly specialized for language, so much so that damage to them results in a serious condition called aphasia, difficulty in producing or comprehending language.

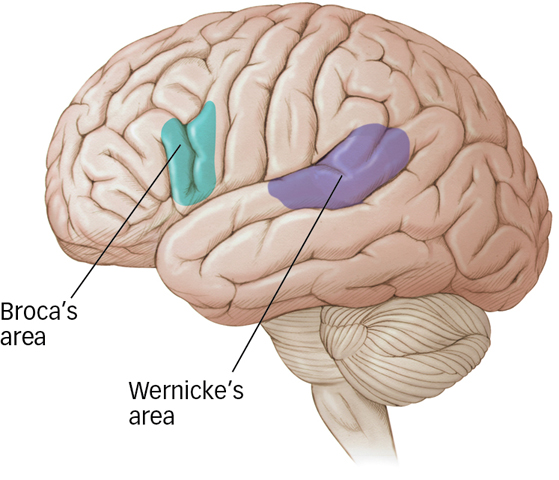

Broca’s area is located in the left frontal cortex and is involved in the production of the sequential patterns in vocal and sign languages (see FIGURE 9.3). As you saw in the Psychology: Evolution of a Science chapter, Broca’s area is named after French physician Paul Broca, who first reported on speech problems resulting from damage to a specific area of the left frontal cortex (Broca, 1861, 1863). Individuals with this damage, resulting in Broca’s aphasia, understand language relatively well, although they have increasing comprehension difficulty as grammatical structures get more complex.

Figure 9.3: Broca’s and Wernicke’s Areas Neuroscientists study people with brain damage in order to better understand how the brain normally operates. When Broca’s area is damaged, people have a hard time producing sentences. When Wernicke’s area is damaged, people can produce sentences, but they tend to be meaningless.

Figure 9.3: Broca’s and Wernicke’s Areas Neuroscientists study people with brain damage in order to better understand how the brain normally operates. When Broca’s area is damaged, people have a hard time producing sentences. When Wernicke’s area is damaged, people can produce sentences, but they tend to be meaningless.

But their real struggle is with speech production. Typically, they speak in short, staccato phrases that consist mostly of content morphemes (e.g., cat, dog). Function morphemes (e.g., and, but) are usually missing and grammatical structure is impaired. A person with the condition might say something like “Ah, Monday, uh, Casey park. Two, uh, friends, and, uh, 30 minutes.”

Wernicke’s area, located in the left temporal cortex, is involved in language comprehension (whether spoken or signed). German neurologist Carl Wernicke first described the area that bears his name after observing speech difficulty in patients who had sustained damage to the left posterior temporal cortex (Wernicke, 1874). Individuals with Wernicke’s aphasia differ from those with Broca’s aphasia in two ways: They can produce grammatical speech, but it tends to be meaningless, and they have considerable difficulty comprehending language. A person suffering from Wernicke’s aphasia might say something like, “Feel very well. In other words, I used to be able to work cigarettes. I do not know how. Things I could not hear from are here.”

In normal language processing, Wernicke’s area is highly active when we make judgments about word meaning, and damage to this area impairs comprehension of spoken and signed language, although the ability to identify nonlanguage sounds is unimpaired. For example, Japanese can be written using symbols that, like the English alphabet, represent speech sounds, or by using pictographs that, like Chinese pictographs, represent ideas. Japanese persons who suffer from Wernicke’s aphasia encounter difficulties in writing and understanding the symbols that represent speech sounds but not pictographs (Sasanuma, 1975).

9.2.2 Involvement of the Right Cerebral Hemisphere

As important as Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas are for language, they are not the entire story. Three kinds of evidence indicate that the right cerebral hemisphere also contributes to language processing, especially to language comprehension (Jung-

9.2.3 Bilingualism and the Brain

Around the world, most people grow up speaking more than one language. Bilingualism (or multilingualism) is the norm, rather than the exception. In Canada, over 200 languages are represented, and more than a third of the population speaks more than one language fluently (Statistics Canada, 2012a). (See the Other Voices box for an opinion on the state of bilingualism in Canada.) What is the effect of such rich language development on the brain?

Early studies of bilingual children seemed to suggest that bilingualism slows or interferes with normal cognitive development. When compared with monolingual children, bilingual children performed more slowly when processing language, and their IQ scores were lower. A re-

OTHER VOICES: Canada’s Future Has to Be Bilingual

Canada is a country composed of many different ethnic groups. Multiculturalism is a feature of Canada of which many Canadians are proud. Language is an important part of multiculturalism. Bilingualism when relating to French and English is an important but sometimes contentious subject in Canada as Robert Rothon, the executive director of Canadian Parents for French (in Montreal) can tell you. In 2012, Robert Rothon wrote the following article in The Montreal Gazette to help people understand the most recent statistics on language and to provide a more positive perspective on the issue.

Late last month, Statistics Canada began releasing data on language from the 2011 federal census. Many commentators, particularly in Quebec, interpreted the results negatively, both in terms of trends within Quebec and across all of Canada as far as bilingual and French speakers are concerned.

However, Canadian Parents for French, a pan-

First of all, it is not true that the percentage of French-

In Quebec, close to 98 percent of the population speaks French or English, and of this group, a significant number speak both languages.

In addition, the number of people who identify their mother tongue as both English and French has been increasing since 2006.

The census also provided information linking Canada’s linguistic landscape to its labour force. Here, CPF would like to underline the fact that official-

All of this points to the increasing presence and value of official-

Some of the francophone organizations working on behalf of French first-

Nationally, official-

French is far from disappearing from Canada.

Currently, no language is on track to outnumber French as Canada’s second most widely spoken language. Punjabi comes in at a distant third, with not quite 500,000 speakers, in contrast to the 21 percent of Canadians who can speak French.

Many parents who don’t speak one of Canada’s two official languages are trying to enrol their children in French-

In Quebec, Montreal is an excellent example of how official-

A strong case can be made that Montreal is the city that attracts the best and brightest of official-

With the release of the 2011 census, it is easy to see how linguistic duality is linked—

Are you convinced by Rothon’s arguments? If not, why? And if so, how far do you think that the educational system should go in promoting multilingual education? What about the possible impact of devoting more time in early grades to teaching languages rather than other subjects? What kinds of research would you want to see done to evaluate the effects of early instruction in second-

Robert Rothon and Shaunpal Jandu, “Opinion: Happily, Canadian bilingualism on the rise,” Montreal Gazette, November 21, 2012. By permission of Robert Rothon, Executive Director, Canadian Parents for French.

Later studies controlled for these factors, revealing a very different picture of bilingual children’s cognitive skills. The available evidence concerning language acquisition indicates that bilingual and monolingual children do not differ significantly in the course and rate of many aspects of their language development (Nicoladis & Genesee, 1997). In fact, middle-

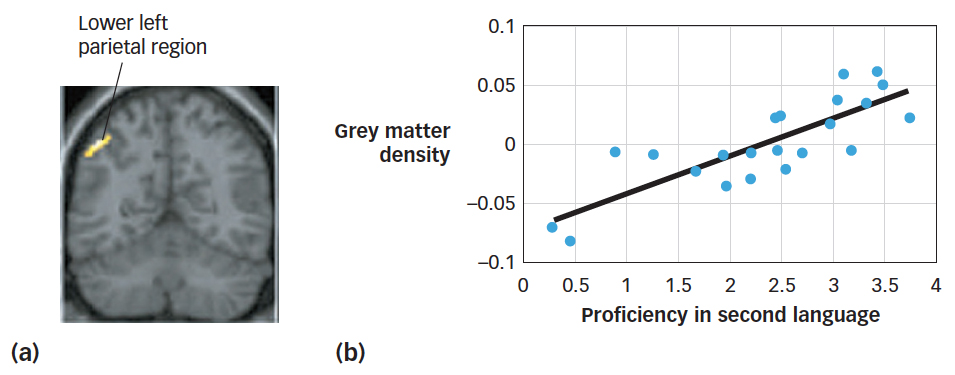

Figure 9.4: Bilingualism Alters Brain Structure Learning a second language early in life increases the density of grey matter in the brain. (a) A view of the lower left parietal region, which has denser grey matter in bilingual relative to monolingual individuals. (b) As proficiency in a second language increases, so does the density of grey matter in the lower parietal region. People who acquired a second language earlier in life were also found to have denser grey matter in this region. Interestingly, this area corresponds to the same area that is activated during verbal fluency tasks (Mechelli et al., 2004).

Figure 9.4: Bilingualism Alters Brain Structure Learning a second language early in life increases the density of grey matter in the brain. (a) A view of the lower left parietal region, which has denser grey matter in bilingual relative to monolingual individuals. (b) As proficiency in a second language increases, so does the density of grey matter in the lower parietal region. People who acquired a second language earlier in life were also found to have denser grey matter in this region. Interestingly, this area corresponds to the same area that is activated during verbal fluency tasks (Mechelli et al., 2004).

Some studies have revealed disadvantages, however. Bilingual children tend to have a smaller vocabulary in each language than their monolingual peers (Portocarrero, Burright, & Donovick, 2007); they also process language more slowly than monolingual children and can sometimes take longer to formulate sentences (Bialystok, 2009; Taylor & Lambert, 1990). Thus, learning a second language produces a number of benefits along with some costs.

9.2.4 Can Other Species Learn Human Language?

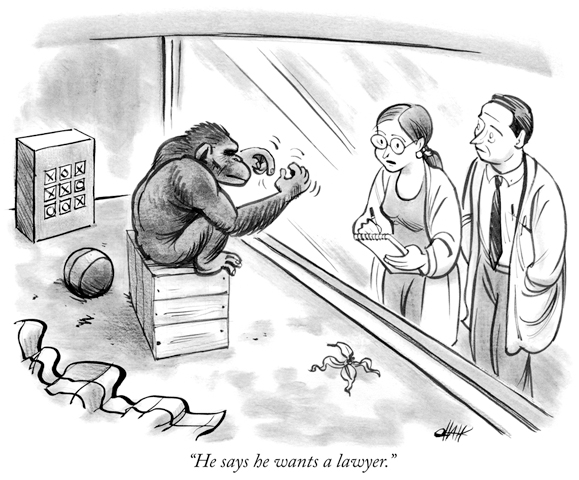

The human vocal tract and the extremely nimble human hand are better suited to human language than are the throats and paws of other species. Nonetheless, attempts have been made to teach nonhuman animals, particularly apes, to communicate using human language.

Early attempts to teach apes to speak failed dismally because their vocal tracts cannot accommodate the sounds used in human languages (Hayes & Hayes, 1951). Later attempts to teach apes human language have met with more success, including teaching them to use American Sign Language and computer-

Other chimpanzees were immersed in ASL in a similar fashion, and Washoe and her companions were soon signing to each other, creating a learning environment conducive to language acquisition. One of Washoe’s cohorts, a chimpanzee named Lucy, learned to sign “drink fruit” for watermelon. When Washoe’s second infant died, her caretakers arranged for her to adopt an infant chimpanzee named Loulis.

In a few months, young Loulis, who was not exposed to human signers, learned 68 signs simply by watching Washoe communicate with the other chimpanzees. People who have observed these interactions and are themselves fluent in ASL report little difficulty in following the conversations (Fouts & Bodamer, 1987). One such observer, a New York Times reporter who spent some time with Washoe, reported, “Suddenly I realized I was conversing with a member of another species in my native tongue.”

Other researchers have taught bonobo chimpanzees to communicate using a geometric keyboard system (Savage-

Kanzi has learned hundreds of words and has combined them to form thousands of word combinations. Also like human children, his passive mastery of language appears to exceed his ability to produce language. In one study, researchers tested 9-

What do studies of apes and language teach us about humans and language?

These results indicate that apes can acquire sizable vocabularies, string words together to form short sentences, and process sentences that are grammatically complex. Their skills are especially impressive because human language is hardly their normal means of communication. Research with apes also suggests that the neurological “wiring” that allows us to learn language overlaps to some degree with theirs (and perhaps with other species’).

Equally informative are the limitations apes exhibit when learning, comprehending, and using human language. The first limitation is the size of the vocabularies they acquire. As mentioned, Washoe’s and Kanzi’s vocabularies number in the hundreds, but an average 4-

The third and perhaps most important limitation is the complexity of grammar that apes can use and comprehend. Apes can string signs together, but their constructions rarely exceed three or four words, and when they do, they are rarely grammatical. Comparing the grammatical structures produced by apes with those produced by human children highlights the complexity of human language as well as the ease and speed with which we generate and comprehend it.

Our abilities to produce and comprehend language depend on distinct regions of the brain, with Broca’s area critical for language production and Wernicke’s area critical for comprehension.

Bilingual and monolingual children show similar rates of language development. However, some bilingual children show greater executive control capacities, such as the ability to prioritize information and flexibly focus attention, and they tend to have a later onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Nonhuman primates can learn new vocabulary and construct simple sentences, but there are significant limitations on the size of their vocabularies and the grammatical complexity they can handle.