15.9 Self-Harm Behaviours: When the Mind Turns against Itself

We all have an innate drive to keep ourselves alive. We eat when we are hungry, get out of the way of fast-

15.9.1 Suicidal Behaviour

Tim, a 35-

Suicide, which refers to intentional self-

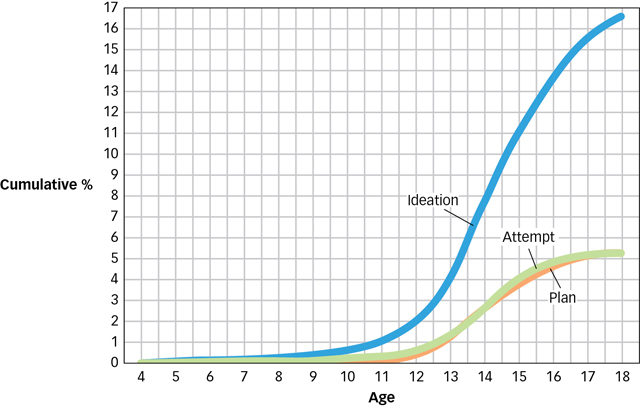

Nonfatal suicide attempt, in which a person engages in potentially harmful behaviour with some intention of dying, occurs much more frequently than suicide deaths. Across a range of countries, approximately 9 percent of adults report that they have seriously considered suicide at some point in their lives, 5 percent have made a plan to kill themselves, and 5 percent have actually made a suicide attempt (Nock et al., 2008). As these numbers suggest, only one third of those who think about suicide actually go on to make a suicide attempt. Although many more men than women die by suicide, women experience suicidal thoughts and (nonfatal) suicide attempts at significantly higher rates than do men (Nock et al., 2008). Moreover, the rates of suicidal thoughts and attempts increase dramatically during adolescence and young adulthood. A recent study of a representative sample of approximately 10 000 adolescents in the United States revealed that suicidal thoughts and behaviours are virtually nonexistent before age 10, but then increase dramatically from age 12 to 18 years (see FIGURE 15.7) before leveling off during early adulthood (Nock et al., 2013).

Figure 15.7: Age of Onset of Suicidal Behaviour During Adolescence A recent survey of adolescents in the United States shows that although suicidal thoughts and behaviours are quite rare among children (the rate was 0.0 for ages 1 to 4), they increase dramatically starting at age 12 and continuing to climb throughout adolescence.

Figure 15.7: Age of Onset of Suicidal Behaviour During Adolescence A recent survey of adolescents in the United States shows that although suicidal thoughts and behaviours are quite rare among children (the rate was 0.0 for ages 1 to 4), they increase dramatically starting at age 12 and continuing to climb throughout adolescence.(Adapted from Nock et al., 2013.)

What are some of the factors that contribute to suicidal behaviour?

The numbers are staggering, but why do people try to kill themselves? The short answer is: We do not yet know, and it is complicated. When interviewed in the hospital following their suicide attempt, most people who have tried to kill themselves report that they did so in order to escape from an intolerable state of mind or impossible situation (Boergers, Spirito, & Donaldson, 1998). Consistent with this explanation, research has documented that the risk of suicidal behaviour is significantly increased if a person experiences factors that can create severely distressing states such as the presence of multiple mental disorders (more than 90 percent of people who die by suicide have at least one mental disorder); the experience of significant negative life events during childhood and adulthood (e.g., physical and sexual assault); and the presence of severe medical problems (Nock, Borges, & Ono, 2012). The search is ongoing for a more comprehensive understanding of how and why some people respond to negative life events with suicidal thoughts and behaviours, as well as on methods of better predicting and preventing these devastating outcomes.

15.9.2 Non-suicidal Self-Injury

Louisa, an 18-

Louisa is engaging in a behaviour called non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), the direct, deliberate destruction of body tissue in the absence of any intent to die. NSSI has been reported since the beginning of recorded history; however, it is a behaviour that appears to be on the rise over the past few decades. Recent studies suggest that as many as 15 to 20 percent of adolescents and 3 to 6 percent of adults report engaging in NSSI at some point in their lifetime (Klonsky, 2011; Muehlenkamp et al., 2012). The rates appear to be even between males and females, and for people of different races and ethnicities. Like suicidal behaviour, NSSI is virtually absent during childhood, increases dramatically during adolescence, and then appears to decrease across adulthood.

What is known so far about why people engage in self-

In some parts of the world, cutting or scarification of the skin is socially accepted, and in some cases encouraged as a rite of passage (Favazza, 2011). In parts of the world where self-

Unfortunately, like suicidal behaviour, our understanding of the genetic and neurobiological influences on NSSI is limited, and there currently are no effective medications for these problems. There also is very limited evidence for behavioural interventions or prevention programs (Mann et al., 2005). So, whereas suicidal behaviour and NSSI are some of the most disturbing and dangerous mental disorders, they also, unfortunately, are among the most perplexing. The field has made significant strides in our understanding of these behaviour problems in recent years, but there is a long way to go before we are able to predict and prevent them accurately and effectively.

Suicide is among the leading causes of death. Most people who die by suicide have a mental disorder, and suicide attempts are most often motivated by an attempt to escape intolerable mental states or situations.

NSSI, like suicidal behaviour, increases dramatically during adolescence, but for many is a persistent problem throughout adulthood. Although NSSI is performed without suicidal intent, like suicidal behaviour, it is most often motivated by an attempt to escape from painful mental states.