1.4 Return of the Mind: Psychology Expands

Watson, Skinner, and the behaviourists dominated psychology from the 1930s to the 1950s. Psychologist Ulric Neisser recalled the atmosphere when he was a student in the early 1950s:

Behaviorism was the basic framework for almost all of psychology at the time. It was what you had to learn. That was the age when it was supposed that no psychological phenomenon was real unless you could demonstrate it in a rat. (quoted in Baars, 1986, p. 275)

Behaviourism would not dominate the field for much longer, however, and Neisser himself would play an important role in developing an alternative perspective. Why was behaviourism replaced? Although behaviourism allowed psychologists to measure, predict, and control behaviour, it did this by ignoring some important things. First, it ignored the mental processes that had fascinated psychologists such as Wundt and James and, in so doing, found itself unable to explain some very important phenomena, such as how children learn language. Second, it ignored the evolutionary history of the organisms it studied and was thus unable to explain why, for example, a rat could learn to associate nausea with food much more quickly than it could learn to associate nausea with a tone or a light. As we will see, the approaches that ultimately replaced behaviourism met these kinds of problems head-

1.4.1 The Pioneers of Cognitive Psychology

Even at the height of behaviourist domination, there were a few revolutionaries whose research and writings were focused on mental processes. German psychologist Max Wertheimer (1880–

Why might people not see what an experimenter actually showed them?

Another pioneer who focused on the mind was Sir Frederic Bartlett (1886–

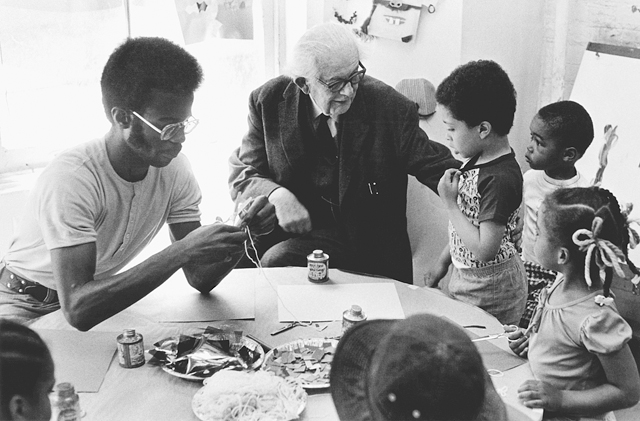

Jean Piaget (1896–

German psychologist Kurt Lewin (1890–

How did the advent of computers change psychology?

But, aside from a handful of pioneers such as these, psychologists happily ignored mental processes until the 1950s, when something important happened: the computer. The advent of computers had enormous practical impact, of course, but it also had an enormous conceptual impact on psychology. People and computers differ in important ways, but both seem to register, store, and retrieve information, leading psychologists to wonder whether the computer might be useful as a model for the human mind. Computers are information-

1.4.2 Technology and the Development of Cognitive Psychology

Although the contributions of psychologists such as Wertheimer, Bartlett, Piaget, and Lewin provided early alternatives to behaviourism, they did not depose it. That job required the Army. During World War II, the military turned to psychologists to help understand how soldiers could best learn to use new technologies, such as radar. Radar operators had to pay close attention to their screens for long periods while trying to decide whether blips were friendly aircraft, enemy aircraft, or flocks of wild geese in need of a good chasing (Ashcraft, 1998; Lachman, Lachman, & Butterfield, 1979). How could radar operators be trained to make quicker and more accurate decisions? The answer to this question clearly required more than the swift delivery of pellets to the radar operator’s food tray. It required that those who designed the equipment think about and talk about cognitive processes, such as perception, attention, identification, memory, and decision making. Behaviourism solved the problem by denying it, so some psychologists decided to deny behaviourism and forge ahead with a new approach.

British psychologist Donald Broadbent (1926–

What did psychologists learn from pilots during World War II?

As you have already read, the invention of the computer in the 1950s had a profound impact on psychologists’ thinking. A computer is made of hardware (e.g., chips and disk drives today; magnetic tapes and vacuum tubes a half-

Ironically, the emergence of cognitive psychology was also energized by the appearance of B. F. Skinner’s (1957) book, Verbal Behaviour, which offered a behaviourist analysis of language. A linguist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Noam Chomsky (b. 1928), published a devastating critique of the book in which he argued that Skinner’s insistence on observable behaviour had caused him to miss some of the most important features of language. According to Chomsky, language relies on mental rules that allow people to understand and produce novel words and sentences. The ability of even the youngest child to generate new sentences that he or she had never heard before flew in the face of the behaviourist claim that children learn to use language by reinforcement. Chomsky provided a clever, detailed, and thoroughly cognitive account of language that could explain many of the phenomena that the behaviourist account could not (Chomsky, 1959).

These developments during the 1950s set the stage for an explosion of cognitive studies during the 1960s. Cognitive psychologists did not return to the old introspective procedures used during the nineteenth century, but instead developed new and ingenious methods that allowed them to study cognitive processes. The excitement of the new approach was summarized in a landmark book, Cognitive Psychology, written by someone you met earlier in this chapter, Ulric Neisser. Neisser’s (1967) book provided a foundation for the development of cognitive psychology, which grew and thrived in the years that followed.

1.4.3 The Brain Meets the Mind: The Rise of Cognitive Neuroscience

If cognitive psychologists studied the software of the mind, they had little to say about the hardware of the brain. And yet, as any computer scientist knows, the relationship between software and hardware is crucial: Each element needs the other to get the job done. Our mental activities often seem so natural and effortless—

Karl Lashley (1890–

Of course, experimental brain surgery cannot ethically be performed on human beings; thus, psychologists who want to study the human brain often have to rely on nature’s cruel and inexact experiments. Birth defects, accidents, and illnesses often cause damage to particular brain regions and, if that damage disrupts a particular ability, then psychologists deduce that the region is involved in producing the ability. For example, in the Memory chapter you will learn about a patient whose memory was virtually eliminated by damage to a specific part of the brain, and you will see how this tragedy provided scientists with remarkable clues about how memories are stored (Scoville & Milner, 1957). Fortunately in the late 1980s, technological breakthroughs led to the development of noninvasive brain scanning techniques that made it possible for psychologists to watch what happens inside a human brain as a person performs a task such as reading, imagining, listening, and remembering. Brain scanning is an invaluable tool because it allows us to observe the brain in action and to see which parts are involved in which operations (see the Neuroscience and Behaviour chapter).

What have we learned by watching the brain at work?

For example, researchers used scanning technology to identify the parts of the brain in the left hemisphere that are involved in specific aspects of language, such as understanding or producing words (Peterson et al., 1989). Later scanning studies showed that people who are deaf from birth, but who learn to communicate using American Sign Language (ASL), rely on regions in the right hemisphere (as well as the left) when using ASL. In contrast, people with normal hearing who learned ASL after puberty seemed to rely only on the left hemisphere when using ASL (Newman et al., 2002). These findings suggest that although both spoken and signed language usually rely on the left hemisphere, the right hemisphere also can become involved—

Figure 1.2: PET Scans of Healthy and Alzheimer’s Brains PET scans are one of a variety of brain imaging technologies that psychologists use to observe the living brain. The four brain images on the top each come from a person suffering from Alzheimer’s disease; the four on the bottom each come from a healthy person of similar age. The red and green areas reflect higher levels of brain activity compared to the blue areas, which reflect lower levels of activity. In each image, the front of the brain is on the top and the back of the brain is on the bottom. You can see that the person with Alzheimer’s disease, compared with the healthy person, shows more extensive areas of lowered activity toward the front of the brain.

Figure 1.2: PET Scans of Healthy and Alzheimer’s Brains PET scans are one of a variety of brain imaging technologies that psychologists use to observe the living brain. The four brain images on the top each come from a person suffering from Alzheimer’s disease; the four on the bottom each come from a healthy person of similar age. The red and green areas reflect higher levels of brain activity compared to the blue areas, which reflect lower levels of activity. In each image, the front of the brain is on the top and the back of the brain is on the bottom. You can see that the person with Alzheimer’s disease, compared with the healthy person, shows more extensive areas of lowered activity toward the front of the brain.

1.4.4 The Adaptive Mind: The Emergence of Evolutionary Psychology

Psychology’s renewed interest in mental processes and its growing interest in the brain were two developments that led psychologists away from behaviourism. A third development also pointed them in a different direction. Recall that one of behaviourism’s key claims was that organisms are blank slates on which experience writes its lessons, and hence any one lesson should be as easily written as another. But in experiments conducted during the 1960s and 1970s, psychologist John Garcia and his colleagues showed that rats can learn to associate nausea with the smell of food much more quickly than they can learn to associate nausea with a flashing light (Garcia, 1981). Why should this be? In the real world of forests, sewers, and garbage cans, nausea is usually caused by spoiled food and not by lightning, and although these particular rats had been born in a laboratory and had never left their cages, millions of years of evolution had prepared their brains to learn the natural association more quickly than the artificial one. In other words, it was not only the rat’s learning history but the rat’s ancestors’ learning histories that determined the rat’s ability to learn.

Although that fact was at odds with the behaviourist doctrine, it was the credo for a new kind of psychology. Evolutionary psychology explains mind and behaviour in terms of the adaptive value of abilities that are preserved over time by natural selection. Evolutionary psychology has its roots in Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, which, as we saw earlier, holds that the features of an organism that help it survive and reproduce are more likely than other features to be passed on to subsequent generations.

This theory inspired the functionalist approaches of William James and G. Stanley Hall because it led them to focus on how mental abilities help people to solve problems and therefore increase their chances of survival. But it is only since the publication in 1975 of Sociobiology, by the biologist E. O. Wilson, that evolutionary thinking has had an identifiable presence in psychology. That presence is steadily increasing (Buss, 1999; Pinker, 1997a, 1997b; Tooby & Cosmides, 2000). Evolutionary psychologists think of the mind as a collection of specialized “modules” that are designed to solve the human problems our ancestors faced as they attempted to eat, mate, and reproduce over millions of years. According to evolutionary psychology, the brain is not an all-

Consider, for example, how evolutionary psychology treats the emotion of jealousy. All of us who have been in romantic relationships have experienced jealousy, if only because we noticed our partner noticing someone else. Jealousy can be a powerful, overwhelming emotion that we might wish to avoid but, according to evolutionary psychology, it exists today because it once served an adaptive function. If some of our hominid ancestors experienced jealousy and others did not, then the ones who experienced it might have been more likely to guard their mates and threaten their rivals and thus may have been more likely to reproduce their “jealous genes” (Buss, 2000, 2007; Buss & Haselton, 2005).

Critics of the evolutionary approach point out that many traits of modern humans and other animals probably evolved to serve different functions than those they currently serve. For example, biologists believe that the feathers of birds probably evolved initially to perform such functions as regulating body temperature or capturing prey and only later served the entirely different function of flight. Likewise, people are reasonably adept at learning to drive a car, but nobody would argue that such an ability is the result of natural selection; the learning abilities that allow us to become skilled car drivers must have evolved for purposes other than driving cars.

Complications such as these have led the critics to wonder how evolutionary hypotheses can ever be tested (Coyne, 2000; Sterelny & Griffiths, 1999). We do not have a record of our ancestors’ thoughts, feelings, and actions, and fossils will not provide much information about the evolution of mind and behaviour. Testing ideas about the evolutionary origins of psychological phenomena is indeed a challenging task, but not an impossible one (Buss et al., 1998; Pinker, 1997a, 1997b).

What evidence suggests that some traits can be inherited?

Start with the assumption that evolutionary adaptations should also increase reproductive success. So, if a specific trait or feature has been favoured by natural selection, it should be possible to find some evidence of this in the numbers of offspring that are produced by the trait’s bearers. Consider, for instance, the hypothesis that men tend to have deep voices because women prefer to mate with baritones rather than sopranos. To investigate this hypothesis, researchers studied a group of modern hunter-

Psychologists such as Max Wertheimer, Frederic Bartlett, Jean Piaget, and Kurt Lewin defied the behaviourist doctrine and studied the inner workings of the mind. Their efforts, as well as those of later pioneers such as Donald Broadbent, paved the way for cognitive psychology to focus on inner mental processes such as perception, attention, memory, and reasoning.

Cognitive psychology developed as a field due to the invention of the computer, psychologists efforts to improve the performance of the military, and Noam Chomsky’s theories about language.

Cognitive neuroscience attempts to link the brain with the mind by studying individuals with brain damage (connecting the area damaged with the loss of specific abilities) and individuals without brain damage, using brain scanning techniques.

Evolutionary psychology focuses on the adaptive function that minds and brains serve and seeks to understand the nature and origin of psychological processes in terms of natural selection.