15.1 Defining Mental Disorders: What Is Abnormal?

The concept of a mental disorder is one of those things that seems simple at first glance, but turns out to be very complex and quite tricky (similar to clearly defining “consciousness,” “stress,” or “personality”). Any extreme variation in your thoughts, feelings, or behaviours is not a mental disorder. For instance, severe anxiety before a test, sadness after the loss of a loved one, or a night of excessive alcohol consumption—

So what is a mental disorder? Perhaps surprisingly, there is not universal agreement on a precise definition of the term “mental disorder.” However, there is general agreement that a mental disorder can be defined as a persistent disturbance or dysfunction in behaviour, thoughts, or emotions that causes significant distress or impairment (Stein et al., 2010; Wakefield, 2007). One way to think about mental disorders is as dysfunctions or deficits in the normal human psychological processes you have learned about throughout this textbook. People with mental disorders have problems with their perception, memory, learning, emotion, motivation, thinking, and social processes. You might ask: But this is still a broad definition, so what kinds of disturbances “count” as mental disorders? How long must they last to be considered “persistent?” And how much distress or impairment is required? These are all hotly debated questions in the field. They have been for many years, and likely will be for years to come (as discussed in more detail later).

15.1.1 Conceptualizing Mental Disorders

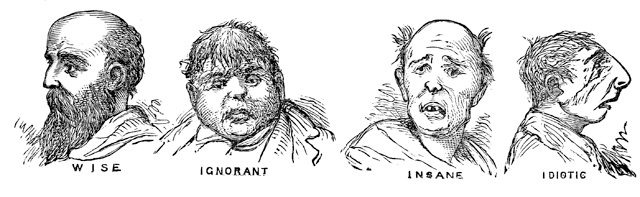

Historically speaking, there are reports of people acting strangely or reporting bizarre thoughts or emotions since ancient times. Until fairly recently, such difficulties were conceptualized as the result of religious or supernatural forces. In some cultures, psychopathology is still interpreted as possession by spirits or demons, as enchantment by a witch or shaman, or as God’s punishment for wrongdoing. In many societies, including our own, people with psychological disorders have been feared and ridiculed, and often treated as criminals: punished, imprisoned, or put to death for their “crime” of deviating from the normal.

Over the past 200 years, these ways of looking at psychological abnormalities have largely been replaced in most parts of the world by a medical model, in which abnormal psychological experiences are conceptualized as illnesses that, like physical illnesses, have biological and environmental causes, defined symptoms, and possible cures. Conceptualizing abnormal thoughts and behaviours as illness suggests that a first step is to determine the nature of the problem through diagnosis.

What is the first step in helping someone with a psychological disorder?

In diagnosis, clinicians seek to determine the nature of a person’s mental disorder by assessing signs (objectively observed indicators of a disorder) and symptoms (subjectively reported behaviours, thoughts, and emotions) that suggest an underlying illness. So, for example, just as a self-

A disorder refers to a common set of signs and symptoms;

A disease is a known pathological process affecting the body; and

A diagnosis is a determination as to whether a disorder or disease is present (Kraemer, Shrout, & Rubio-

Stipec, 2007).

Importantly, knowing that a disorder is present (i.e., diagnosed) does not necessarily mean that we know the underlying disease process in the body that gives rise to the signs and symptoms of the disorder.

Viewing mental disorders as medical problems reminds us that people who are suffering deserve care and treatment, not condemnation. Nevertheless, there are some criticisms of the medical model. Some psychologists argue that it is inappropriate to use clients’ subjective self-

15.1.2 Classifying Mental Disorders

So how is the medical model used to classify the wide range of abnormal behaviours that occur among humans? Psychologists, psychiatrists (physicians concerned with the study and treatment of mental disorders) and most other people working in the area of mental disorders use a standardized system for classifying mental disorders. There are currently two established systems for classifying mental disorders: The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-

How has the DSM changed over time?

The next two editions of the DSM (DSM–

In May, 2013, the American Psychiatric Association released an updated manual: DSM–

|

1. |

Neurodevelopmental Disorders: These are conditions that begin early in development and cause significant impairments in functioning, such as intellectual disability (formerly called “mental retardation”), autism spectrum disorder, and attention- |

|

2. |

Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders: This is a group of disorders characterized by major disturbances in perception, thought, language, emotion, and behaviour. |

|

3. |

Bipolar and Related Disorders: These disorders include major fluctuations in mood— |

|

4. |

Depressive Disorders: These are conditions characterized by extreme and persistent periods of depressed mood. |

|

5. |

Anxiety Disorders: These are disorders characterized by excessive fear and anxiety that are extreme enough to impair a person’s functioning, such as panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. |

|

6. |

Obsessive- |

|

7. |

Trauma- |

|

8. |

Dissociative Disorders: These are conditions characterized by disruptions or discontinuity in consciousness, memory, or identity, such as dissociative identity disorder (formerly called “multiple personality disorder”). |

|

9. |

Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders: These are conditions in which a person experiences bodily symptoms (e.g., pain, fatigue) associated with significant distress or impairment. |

|

10. |

Feeding and Eating Disorders: These are problems with eating that impair health or functioning, such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. |

|

11. |

Elimination Disorders: These involve inappropriate elimination of urine or feces (e.g., bed- |

|

12. |

Sleep– |

|

13. |

Sexual Dysfunctions: These are problems related to unsatisfactory sexual activity, such as erectile disorder and premature ejaculation. |

|

14. |

Gender Dysphoria: This is a single disorder characterized by incongruence between a person’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender. |

|

15. |

Disruptive, Impulse- |

|

16. |

Substance- |

|

17. |

Neurocognitive Disorders: These are disorders of thinking caused by conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease or traumatic brain injury. |

|

18. |

Personality Disorders: These are enduring patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving that lead to significant life problems. |

|

19. |

Paraphilic Disorders: These are conditions characterized by inappropriate sexual activity, such as pedophilic disorder. |

|

20. |

Other Mental Disorders: This is a residual category for conditions that do not fit into one of the above categories but are associated with significant distress or impairment, such as an unspecified mental disorder due to a medical condition. |

|

21. |

Medication- |

|

22. |

Other Conditions that May be the Focus of Clinical Attention: These include problems related to abuse, neglect, relationship, and other problems. |

|

Source: From DSM– |

|

Each of the 22 chapters in the main body of the DSM–

15.1.3 Causation of Disorders

The medical model of mental disorder suggests that knowing a person’s diagnosis is useful because any given category of mental illness is likely to have a distinctive cause. In other words, just as different viruses, bacteria, or genetic abnormalities cause different physical illnesses, so a specifiable pattern of causes (or etiology) may exist for different psychological disorders. The medical model also suggests that each category of mental disorder is likely to have a common prognosis, a typical course over time and susceptibility to treatment and cure. Unfortunately, this basic medical model is usually an oversimplification; it is rarely useful to focus on a single cause that is internal to the person and that suggests a single cure.

CULTURE & COMMUNITY: What do Mental Disorders Look Like in Different Parts of the World?

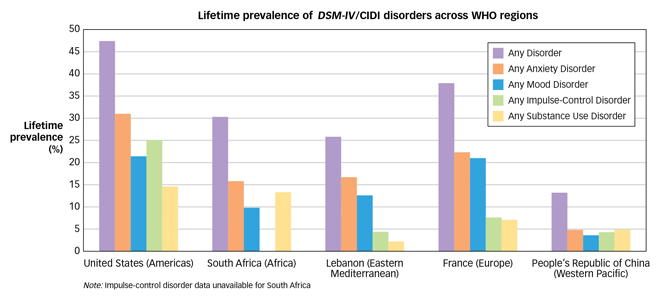

Are the mental disorders that are seen in North America also experienced by people in other parts of the world? In an effort to better understand the epidemiology (the study of the distribution and causes of health and disease) of mental disorders, Ronald Kessler and colleagues launched the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys, a large-

Although all countries appear to have the common mental disorders described above, it is clear that cultural context can influence how mental disorders are experienced, described, assessed, and treated. To address this issue, the DSM–

Why does assessment require looking at a number of factors?

To understand what factors might cause mental disorders, most psychologists take an integrated biopsychosocial perspective that explains mental disorders as the result of interactions among biological, psychological, and social factors. On the biological side, the focus is on genetic and epigenetic influences (see Figure 3.23 in the Neuroscience and Behaviour chapter), biochemical imbalances, and abnormalities in brain structure and function. The psychological perspective focuses on maladaptive learning and coping, cognitive biases, dysfunctional attitudes, and interpersonal problems. Social factors include poor socialization, stressful life experiences, and cultural and social inequities. The complexity of causation suggests that different individuals can experience a similar psychological disorder (e.g., depression) for different reasons. A person might fall into depression as a result of biological causes (e.g., genetics, hormones), psychological causes (e.g., faulty beliefs, hopelessness, poor strategies for coping with loss), environmental causes (e.g., stress or loneliness), or more likely as a result of some combination of these factors. And, of course, multiple causes mean there may not be one single cure.

What are the limitations of using brain scans for diagnosing mental disorders?

The observation that most disorders have both internal (biological and psychological) and external (environmental) causes has given rise to a theory known as the diathesis-stress model, which suggests that a person may be predisposed for a psychological disorder that remains unexpressed until triggered by stress. The diathesis is the internal predisposition and the stress is the external trigger. For example, most people were able to cope with their strong emotional reactions to the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001. However, for some who had a predisposition to negative emotions, the horror of the events may have overwhelmed their ability to cope, thereby precipitating a psychological disorder. Although diatheses can be inherited, it is important to remember that heritability is not destiny. A person who inherits a diathesis may never encounter the precipitating stress, whereas someone with little genetic propensity to a disorder may come to suffer from it given the right pattern of stress. The tendency to oversimplify mental disorders by attributing them to single, internal causes is nowhere more evident than in the interpretation of the role of the brain in psychological disorders. Brain scans of people with and without disorders can give rise to an unusually strong impression that psychological problems are internal and permanent, inevitable, and even untreatable. Brain influences and processes are fundamentally important for knowing the full story of psychological disorders, but are not the only chapter in that story.

15.1.4 A New Approach to Understanding Mental Disorders: RDoC

Although the DSM provides a useful framework for classifying disorders, there has been a growing concern over the fact that the findings from scientific research on the biopsychosocial factors that appear to cause psychopathology do not map neatly onto individual DSM diagnoses. Succinctly characterizing the current state of affairs, Thomas R. Insel, Director of the American National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; the primary funder of research on mental disorders in the United States), noted that although many people describe the DSM as a bible, it is more accurate to think of it like a dictionary that provides labels and current definitions: “People think that everything has to match DSM criteria, but you know what? Biology never read that book” (Insel, quoted in Belluck & Carey, 2013, p. A13). In order to better understand what actually causes mental disorders, researchers at the NIMH have proposed a new framework for thinking about mental disorders focused not on the currently defined DSM categories of disorders, but on the more basic biological, cognitive, and behavioural constructs that are believed to be the building blocks of mental disorders. This new system is called the Research Domain Criteria Project (RDoC), a new initiative that aims to guide the classification and understanding of mental disorders by revealing the basic processes that give rise to them. The RDoC is not intended to immediately replace the DSM, but to inform future revisions to it in the coming years (see The Real World box).

Using the RDoC, researchers study the causes of abnormal functioning by focusing on biological factors from genes to cells to brain circuits; psychological domains, such as learning, attention, memory; and various social processes and behaviour (see TABLE 15.2 for a list of domains). The hope is that the RDoC approach will lead to more progress in understanding the underlying causes of mental disorders than does a focus on the traditional labels, and will also reveal links between disorders that were not previously suspected. The long-

|

|

Units of Analysis |

|||||||

|

Domain/Construct |

Genes |

Molecules |

Cells |

Circuits |

Physiology |

Behaviour |

Self- |

Paradigms |

|

Negative Valence Systems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Acute threat (“fear”) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Potential threat (“anxiety”) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sustained threat |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loss |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frustrative non- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive Valence Systems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Approach motivation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Initial responsiveness to reward |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sustained responsiveness to reward |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reward learning |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Habit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cognitive Systems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Attention |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perception |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Working memory |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Declarative memory |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Language behaviour |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cognitive (effortful) control |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Systems for Social Processes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Affiliation and attachment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Social communication |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perception and understanding of self |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perception and understanding of others |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Arousal and Regulatory Systems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Arousal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Circadian rhythms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sleep and wakefulness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE REAL WORLD: How Are Mental Disorders Defined and Diagnosed?

Who decides what goes in the DSM? How are these decisions made? In psychology and psychiatry, as in the early days of most areas of the study of human health and behaviour, these decisions currently are made by consensus among leaders in the research field. These leaders meet repeatedly over several years to make decisions about which disorders should be included in the new revision of the DSM, and how they should be defined. Over the years, these decisions have been based on descriptive research reporting on which clinical symptoms tend to cluster together. Everyone agrees that we need a system for classifying and defining mental disorders; however, as the currently available body of knowledge about mental disorders grows, the field is moving beyond simple descriptive diagnostic categories toward ones based on underlying biopsychosocial processes (i.e., the Research Domain Criteria Project). Future decisions about how mental disorders are defined will likely continue to be reached by consensus among leaders in the field, but will be driven more directly by research on the underlying causes of these disorders.

Who decides whether someone has a diagnosis? And how are these decisions made? Over the years, researchers have developed structured clinical interviews that convert the lists of symptoms included in the DSM into sets of interview questions through which the clinician (psychologist, psychiatrist, social worker) makes a determination about whether or not a given person meets criteria for each disorder (Nock et al., 2007). For instance, according to DSM–

You might have noticed that the list of domains in Table 15.2 looks like a slightly more detailed version of the table of contents for this textbook! The RDoC approach has an overall emphasis on neuroscience (Chapter 3), and specific focuses on abnormalities in emotional and motivational systems (Chapters 8), cognitive systems such as memory (Chapter 6), learning (Chapter 7), language and cognition (Chapter 9), social processes (Chapter 13), and stress and arousal (Chapter 14). From the RDoC perspective, mental disorders can be thought of as the result of abnormalities or dysfunctions in normal psychological processes. By learning about many of these processes in this textbook, you will likely have a good understanding of new definitions of mental disorders as they are developed in the years ahead.

15.1.5 Dangers of Labelling

An important complication in the diagnosis and classification of psychological disorders is the effect of labelling. Psychiatric labels can have negative consequences because many carry the baggage of negative stereotypes and stigma, such as the idea that mental disorder is a sign of personal weakness or the idea that psychiatric patients are dangerous. The stigma associated with mental disorders may explain why most people with diagnosable psychological disorders (approximately 60 percent) do not seek treatment (Kessler, Demler, et al., 2005; Wang, Berglund, et al., 2005).

Why might someone avoid seeking help for a mental illness?

Unfortunately, educating people about mental disorders does not dispel the stigma borne by those with these conditions (Phelan et al., 1997). In fact, expectations created by psychiatric labels can sometimes even compromise the judgment of mental health professionals (Garb, 1998; Langer & Abelson, 1974; Temerlin & Trousdale, 1969). In a classic demonstration of this phenomenon, psychologist David Rosenhan and six associates reported to different mental hospitals complaining of “hearing voices,” a symptom sometimes found in people with schizophrenia. Each was admitted to a hospital, and each promptly reported that the symptom had ceased. Even so, hospital staff were reluctant to identify these people as normal: It took an average of 19 days for these “patients” to secure their release, and even then they were released with the diagnosis of “schizophrenia in remission” (Rosenhan, 1973). Apparently, once hospital staff had labelled these patients as having a psychological disease, the label stuck.

These effects of labelling are particularly disturbing in light of evidence that the hospitalization of people with mental disorders is seldom necessary. One set of studies followed the lives of patients who were thought to be too dangerous to release and therefore had been kept in the back wards of institutions for years. Their release resulted in no harm to the community (Harding et al., 1987), and further studies have shown that those with a mental disorder are no more likely to be violent than those without a disorder (Elbogen & Johnson, 2009; Monahan, 1992).

Labelling may even affect how labelled individuals view themselves; persons given such a label may come to view themselves not just as mentally disordered, but as hopeless or worthless. Such a view may cause them to develop an attitude of defeat and, as a result, to fail to work toward their own recovery. As one small step toward counteracting such consequences, clinicians have adopted the important practice of applying labels to the disorder and not to the person with the disorder. For example, an individual might be described as “a person with schizophrenia,” not as “a schizophrenic.” You will notice that we follow this convention in the textbook.

The DSM–

5 is a classification system that defines a mental disorder as occurring when the person experiences disturbances of thought, emotion, or behaviour that produce distress or impairment and that arise from internal sources.According to the biopsychosocial model, mental disorders arise from an interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors, often thought of as a combination of a diathesis (internal predisposition) and stress (environmental life event).

The RDoC is a new classification system that focuses on biological, cognitive, and behavioural aspects of mental disorders.