16.3 Medical and Biological Treatments: Healing the Mind by Physically Altering the Brain

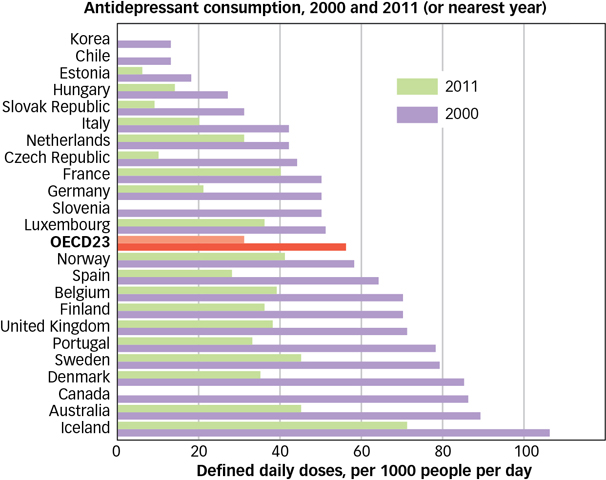

Ever since someone discovered that a whack to the head can affect the mind, people have suspected that direct brain interventions might hold the keys to a cure for psychological disorders. Archaeological evidence, for example, indicates that the occasional human thousands of years ago was “treated” for some malady by the practice of trephining (drilling a hole in the skull), perhaps in the belief that this would release evil spirits that were affecting the mind (Alt et al., 1997). Surgery for psychological disorders is a last resort nowadays, and treatments that focus on the brain usually involve interventions that are less dramatic. The use of drugs to influence the brain was also discovered in prehistory (alcohol, for example, has been around for a long time). Since then, drug treatments have grown in variety, effectiveness, and popularity and they are now the most common medical approach in treating psychological disorders (see FIGURE 16.2).

Figure 16.2: Antidepressant Use The popularity of psychiatric medications has skyrocketed in recent years. A recent report from the Organisation for Economic Co-

Figure 16.2: Antidepressant Use The popularity of psychiatric medications has skyrocketed in recent years. A recent report from the Organisation for Economic Co-16.3.1 Antipsychotic Medications

The story of drug treatments for severe psychological disorders starts in the 1950s, with chlorpromazine (brand name Thorazine), which was originally developed as a sedative, but when administered to people with schizophrenia, often left them euphoric and docile, although they had formerly been agitated and incorrigible (Barondes, 2003). Chlorpromazine was the first in a series of antipsychotic drugs, which treat schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, and completely changed the way schizophrenia was managed. Other related medications, such as thioridazine (Mellaril) and haloperidol (Haldol), followed. Before the introduction of antipsychotic drugs, people with schizophrenia often exhibited bizarre symptoms and were sometimes so disruptive and difficult to manage that the only way to protect them (and other people) was to keep them in hospitals for people with mental disorders, which were initially called asylums but now are referred to as psychiatric hospitals (see The Real World box: Treating Severe Mental Disorders). In the period following the introduction of these drugs, the number of people in psychiatric hospitals decreased by more than two thirds. Antipsychotic drugs made possible the deinstitutionalization of hundreds of thousands of people and gave a major boost to the field of psychopharmacology, the study of drug effects on psychological states and symptoms.

THE REAL WORLD: Treating Severe Mental Disorders

Society has never quite known what to do with people who have severe mental disorders. For much of recorded history, mentally ill people have been victims of maltreatment, languishing as paupers in the streets or, worse, suffering inhumane conditions in prisons. One exception was the medieval Islamic world, in which care and kindness were shown to the insane in hospitals. At his hospital in Cairo, the Egyptian ruler Ahmad ibn Tulun (835 CE–

In medieval Europe, madness was seen as a local problem, with families and local communities assuming responsibility for care. Only a small proportion of the insane (generally those deemed violent or dangerous) were housed institutionally—

By 1700, more asylums for the insane were being created. The creation of asylums encouraged humane treatment but did not guarantee it. The Bethlem Royal Hospital was a charity, and charged visitors to view the inmates as a way of financing the institution. One visitor to this human zoo in 1753 remarked, “To my great surprise, I found at least a hundred people, who, having paid their two pence apiece, were suffered, unattended, to run rioting up and down the wards, making sport and diversion of the miserable inhabitants” (Hitchcock, 2005).

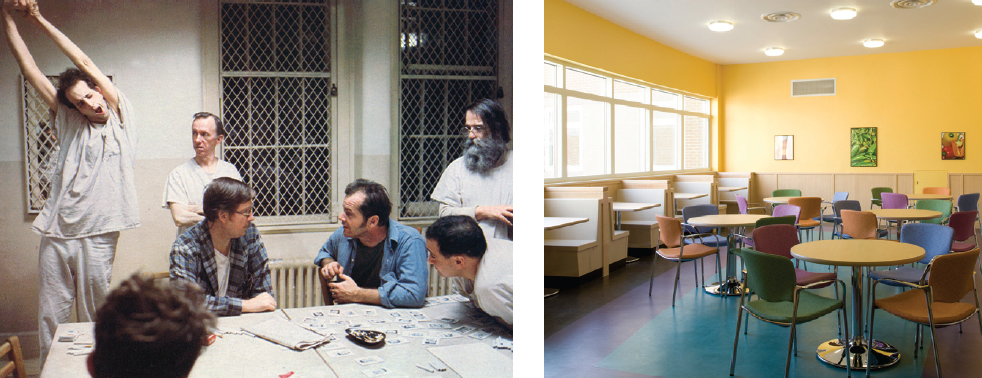

What does a modern psychiatric hospital look like? In Hollywood movies, such as this scene from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, they typically are dirty, scary, painted in a drab grey or green colour, and it is always night time. In the real world, they look just like other hospital units in terms of cleanliness, scariness, paint scheme, and the experience of both day and night.

What does a modern psychiatric hospital look like? In Hollywood movies, such as this scene from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, they typically are dirty, scary, painted in a drab grey or green colour, and it is always night time. In the real world, they look just like other hospital units in terms of cleanliness, scariness, paint scheme, and the experience of both day and night.The Enlightenment period in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century saw a change in how people with mental illness were thought about, and how they were treated. The Enlightenment, closely tied to the Scientific Revolution, was a time when reason and science were seen as ways to reform society, and it became more common to consider mental disorders like other forms of illness that could be treated and cured. Enlightenment figures like Benjamin Rush in the United States and Philippe Pinel in France (both physicians), and William Tuke in Britain established hospitals and asylums in which the insane were not confined, where they received humane treatment, engaged in activities that might now be considered occupational therapy, and from where they could potentially be reintegrated into society.

The eighteenth century asylums were mostly private, but public charitably funded asylums began to spring up about the middle of the 1800s, both in Britain and in North America. By 1900, the number of people with mental illness housed in institutions in France, Britain, the United States, and Canada could be measured in the hundreds of thousands. The age of institutionalization had begun. Despite the early reforms of Pinel, Rush, and others, these institutions were often under-

Has this experiment worked? On one hand, treatment for some severe disorders has improved since deinstitutionalization began. The basic drugs that helped people to manage their lives outside mental hospitals have been refined and improved. In addition, the conditions and treatments available in psychiatric hospitals have improved immensely. Contrary to what you may see in the movies, psychiatric units and hospitals look just like other medical floors in general hospitals. However, the provision of community services did not fully compensate for deinstitutionalization. This has led to difficulties in providing adequate care at the community level. People with severe mental illness too often end up on the streets, where they remain homeless, poor, and vulnerable to danger. Treatment for those with serious mental illness has improved over the past 100 or so years, but we clearly still have a long way to go.

What do antipsychotic drugs do?

Antipsychotic medications are believed to block dopamine receptors in parts of the brain such as the mesolimbic area, an area between the tegmentum (in the midbrain) and various subcortical structures (see the Neuroscience and Behaviour chapter). The medication reduces dopamine activity in these areas. The effectiveness of schizophrenia medications led to the dopamine hypothesis (described in the Psychological Disorders chapter), suggesting that schizophrenia may be caused by excess dopamine in the synapse. Research has indeed found that dopamine overactivity in the mesolimbic area of the brain is related to the more bizarre positive symptoms of schizophrenia, such as hallucinations and delusions (Marangell et al., 2003).

Although antipsychotic drugs work well for positive symptoms, it turns out that negative symptoms of schizophrenia, such as emotional numbing and social withdrawal, may be related to dopamine underactivity in the mesocortical areas of the brain (connections between parts of the tegmentum and the cortex). This may help explain why antipsychotic medications do not relieve negative symptoms well. Instead of a medication that blocks dopamine receptors, negative symptoms require a medication that increases the amount of dopamine available at the synapse. This is a good example of how medical treatments can have broad psychological effects but not target specific psychological symptoms.

What are the advantages of the newer, atypical antipsychotic medications?

After the introduction of antipsychotic medications, there was little change in the available treatments for schizophrenia for more than a quarter of a century. However, in the 1990s, a new class of antipsychotic drugs was introduced. These newer drugs, which include clozapine (Clozaril), risperidone (Risperidal), and olanzepine (Zyprexa), have become known as atypical antipsychotics (the older drugs are now often referred to as conventional or typical antipsychotics). Unlike the older antipsychotic medications, these newer drugs appear to affect both the dopamine and serotonin systems, blocking both types of receptors. The ability to block serotonin receptors appears to be a useful addition because enhanced serotonin activity in the brain has been implicated in some of the core difficulties in schizophrenia, such as cognitive and perceptual disruptions, as well as mood disturbances. This may explain why atypical antipsychotics work at least as well as older drugs for the positive symptoms of schizophrenia and also work fairly well for the negative symptoms (Bradford, Stroup, & Lieberman, 2002).

Like most medications, antipsychotic drugs have side effects. The side effects can be sufficiently unpleasant that some people “go off their meds,” preferring their symptoms to the drug. One side effect that often occurs with long-

16.3.2 Anti-anxiety Medications

What are some reasons for caution when prescribing anti-

Anti-anxiety medications are drugs that help reduce a person’s experience of fear or anxiety. The most commonly used antianxiety medications are the benzodiazepines, a type of tranquilizer that works by facilitating the action of the neurotransmitter gamma-

Nonetheless, these days doctors are relatively cautious when prescribing benzodiazepines. One concern is that these drugs have the potential for abuse. They are often associated with the development of drug tolerance, which is the need for higher dosages over time to achieve the same effects following long-

When anxiety leads to insomnia, drugs known as hypnotics may be useful as sleep aids. One such drug, zolpidem (Ambien), is in wide use and is often effective, but with some reports of sleepwalking, sleep-

16.3.3 Antidepressants and Mood Stabilizers

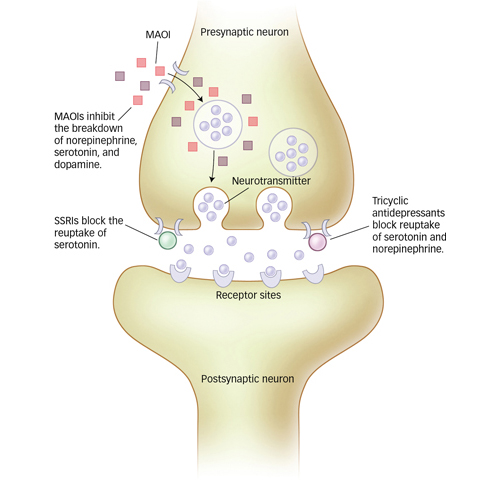

Antidepressants are a class of drugs that help lift people’s moods. They were first introduced in the 1950s, when iproniazid, a drug that was used to treat tuberculosis, was found to elevate mood (Selikoff, Robitzek, & Ornstein, 1952). Iproniazid is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), a medication that prevents the enzyme monoamine oxidase from breaking down neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine. However, despite their effectiveness, MAOIs are rarely prescribed anymore. MAOI side effects such as dizziness and loss of sexual interest are often difficult to tolerate, and these drugs interact with many different medications, including over-

A second category of antidepressants is the tricyclic antidepressants, which were also introduced in the 1950s. These include drugs such as imipramine (Tofranil) and amitriptyline (Elavil). These medications block the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin, thereby increasing the amount of neurotransmitter in the synaptic space between neurons. The most common side effects of tricyclic antidepressants include dry mouth, constipation, difficulty urinating, blurred vision, and racing heart (Marangell et al., 2003). Although these drugs are still prescribed, they are used much less frequently than they were in the past because of these side effects.

What are the most common antidepressants used today? How do they work?

Among the most commonly used antidepressants today are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, which include drugs such as fluoxetine (Prozac), citalopram (Celexa), and paroxetine (Paxil). The SSRIs work by blocking the reuptake of serotonin in the brain, which makes more serotonin available in the synaptic space between neurons. The greater availability of serotonin in the synapse gives the neuron a better chance of “recognizing” and using this neurotransmitter in sending the desired signal. The SSRIs were developed based on hypotheses that low levels of serotonin are a causal factor in depression. Supporting this hypothesis, SSRIs are effective for depression, as well as for a wide range of other problems. SSRIs are called selective because, unlike the tricyclic antidepressants, which work on the serotonin and norepinephrine systems, SSRIs work more specifically on the serotonin system (see FIGURE 16.3).

Figure 16.3: Antidepressant Drug Actions Antidepressant drugs, such as MAOIs, SSRIs, and tricyclic antidepressants, act on neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine by inhibiting their breakdown and blocking reuptake. These actions make more of the neurotransmitter available for release and leave more of the neurotransmitter in the synaptic gap to activate the receptor sites on the postsynaptic neuron. These drugs relieve depression and often alleviate anxiety and other disorders.

Figure 16.3: Antidepressant Drug Actions Antidepressant drugs, such as MAOIs, SSRIs, and tricyclic antidepressants, act on neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine by inhibiting their breakdown and blocking reuptake. These actions make more of the neurotransmitter available for release and leave more of the neurotransmitter in the synaptic gap to activate the receptor sites on the postsynaptic neuron. These drugs relieve depression and often alleviate anxiety and other disorders.

Finally, antidepressants such as Effexor (venlafaxine) and Wellbutrin (ibupropion) offer other alternatives. Effexor is an example of a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI); whereas SSRIs act only upon serotonin, SNRIs act on both serotonin and norepinephrine. Wellbutrin, in contrast, is a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor. These and other newly developed antidepressants appear to have fewer (or at least different) side effects than the tricyclic antidepressants and MAOIs.

Why are antidepressants not prescribed for bipolar disorder?

Most antidepressants can take up to a month before they start to have an effect on mood. Besides relieving symptoms of depression, almost all of the antidepressants effectively treat anxiety disorders, and many of them can resolve other problems, such as eating disorders. In fact, several companies that manufacture SSRIs have marketed their drugs as treatments for anxiety disorders rather than for their antidepressant effects. Although antidepressants can be effective in treating major depression, they are not recommended for treating bipolar disorder, which is characterized by manic or hypomanic episodes (see the Psychological Disorders chapter). Antidepressants are not prescribed because, in the process of lifting one’s mood, they might actually trigger a manic episode in a person with bipolar disorder. Instead, bipolar disorder is treated with mood stabilizers, which are medications used to suppress swings between mania and depression. Commonly used mood stabilizers include lithium and valproate. Even in unipolar depression, lithium is sometimes effective when combined with traditional antidepressants in people who do not respond to antidepressants alone.

Lithium has been associated with possible long-

16.3.4 Herbal and Natural Products

Why are herbal remedies used? Are they actually effective?

In a survey of more than 18 000 Canadians 45 years old and over, approximately 15 percent reported using alternative “medications” such as herbal medicines, megavitamins, homeopathic remedies, or naturopathic remedies to treat anxiety and depression (Crabb & Hunsley, 2011). Major reasons people use these products are that they are easily available over the counter, are less expensive, and are perceived as “natural” alternatives to synthetic or manmade “drugs.” Are herbal and natural products effective in treating mental health problems, or are they just “snake oil?”

The answer to this question is not simple. Currently, herbal products are not considered medications by regulatory agencies like Health Canada, so they are exempt from rigorous research to establish their safety and effectiveness. Instead, herbal products are classified as nutritional supplements and regulated in the same way as food. There is little scientific information about herbal products, including possible interactions with other medications, possible tolerance and withdrawal symptoms, side effects, appropriate dosages, how they work, or even whether they work—

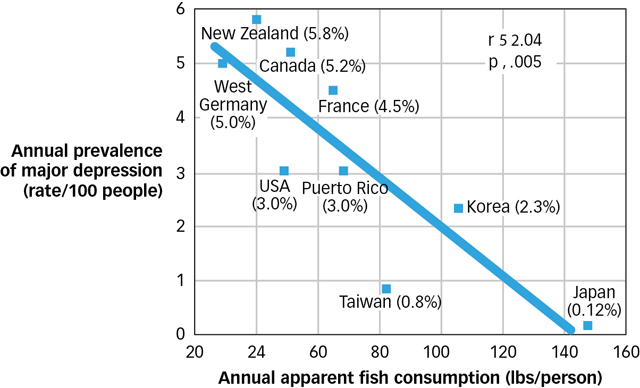

There is research support for the effectiveness of some herbal and natural products, but the evidence is not overwhelming (Lake, 2009). Products such as inositol (a bran derivative), kava (an herb related to black pepper), omega-

Figure 16.4: Omega-

Figure 16.4: Omega-16.3.5 Combining Medication and Psychotherapy

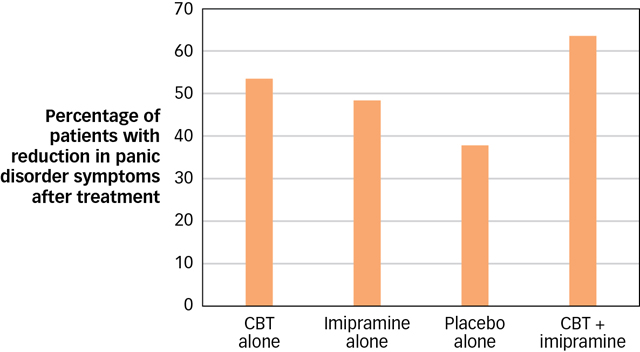

Given that psychological treatments and medications have both shown an ability to treat mental disorders effectively, some natural next questions are: Which is more effective? Is the combination of psychological and medicinal treatments better than either by itself? Many studies have compared psychological treatments, medication, and combinations of these approaches for addressing psychological disorders. The results of these studies often depend on the particular problem being considered. For example, in the cases of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, researchers have found that medication is more effective than psychological treatment and so is considered a necessary part of treatment; recent studies have tended to examine whether adding psychotherapeutic treatments such as social skills training or cognitive behavioural treatment can be helpful (they can). In the case of mood and anxiety disorders, medication and psychological treatments are equally effective. One study compared cognitive behaviour therapy, imipramine (the antidepressant also known as Tofranil), and the combination of these treatments (CBT plus imipramine) with a placebo (administration of an inert medication) for the treatment of panic disorder (Barlow et al., 2000). After 12 weeks of treatment, either CBT alone or imipramine alone was found to be superior to a placebo. For the CBT plus imipramine condition, the response rate also exceeded the rate for the placebo, but was not significantly better than that for either CBT or imipramine alone. In other words, either treatment was better than nothing, but the combination of treatments was not significantly more effective than one or the other (see FIGURE 16.5). More is not always better.

Figure 16.5: The Effectiveness of Medication and Psychotherapy for Panic Disorder One study of CBT and medication (imipramine) for panic disorder found that the effects of CBT, medication, and treatment that combined CBT and medication were not significantly different over the short term, though all three were superior to the placebo condition (Barlow et al., 2000).

Figure 16.5: The Effectiveness of Medication and Psychotherapy for Panic Disorder One study of CBT and medication (imipramine) for panic disorder found that the effects of CBT, medication, and treatment that combined CBT and medication were not significantly different over the short term, though all three were superior to the placebo condition (Barlow et al., 2000).

OTHER VOICES: Diagnosis: Human

Should more people receive psychological treatment or medications? Or should fewer? On one hand, data indicate that most people with a mental disorder do not receive treatment and that untreated mental disorders are an enormous source of pain and suffering. On the other hand, some argue that we have become too quick to label normal human behaviour as “disordered” and too willing to medicate any behaviour, thought, or feeling that makes us uncomfortable. Ted Gup is one of these people. The following is a version of his op-

The news that 11 percent of school-

In his case, he was in the first grade. Indeed, there were psychiatrists who prescribed medication for him even before they met him. One psychiatrist said he would not even see him until he was medicated. For a year I refused to fill the prescription at the pharmacy. Finally, I relented. And so David went on Ritalin, then Adderall, and other drugs that were said to be helpful in combating the condition.

In another age, David might have been called “rambunctious.” His battery was a little too large for his body. And so he would leap over the couch, spring to reach the ceiling and show an exuberance for life that came in brilliant microbursts.

As a 21-

My son was no angel (though he was to us) and he was known to trade in Adderall, to create a submarket in the drug among his classmates who were themselves all too eager to get their hands on it. What he did cannot be excused, but it should be understood. What he did was to create a market that perfectly mirrored the society in which he grew up, a culture where Big Pharma itself prospers from the off-

And so a generation of students, raised in an environment that encourages medication, are emulating the professionals by using drugs in the classroom as performance enhancers. And we wonder why it is that they use drugs with such abandon. As all parents learn—

The issue of permissive drug use and over-

One of the new, more controversial provisions expands depression to include some forms of grief. On its face it makes sense. The grieving often display all the common indicators of depression—

Ours is an age in which the airwaves and media are one large drug emporium that claims to fix everything from sleep to sex. I fear that being human is itself fast becoming a condition. It is as if we are trying to contain grief, and the absolute pain of a loss like mine. We have become increasingly disassociated and estranged from the patterns of life and death, uncomfortable with the messiness of our own humanity, aging and, ultimately, mortality.

Challenge and hardship have become pathologized and monetized. Instead of enhancing our coping skills, we undermine them and seek shortcuts where there are none, eroding the resilience upon which each of us, at some point in our lives, must rely. Diagnosing grief as a part of depression runs the very real risk of delegitimizing that which is most human—

The DSM would do well to recognize that a broken heart is not a medical condition, and that medication is ill-

But there is a sweetness even to the intensity of this pain I feel. It is the thing that holds me still to my son. And yes, there is a balm even in the pain. I shall let it go when it is time, without reference to the DSM, and without the aid of a pill.

Have we gone too far in labelling and treatment of mental disorders? Or have we not gone far enough? How can we make sure that we are not medicating normal behaviour, while at the same time ensuring that we provide help to those who are suffering with a true mental disorder?

From the New York Times, April 3, 2013 © 2013 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited. http:/

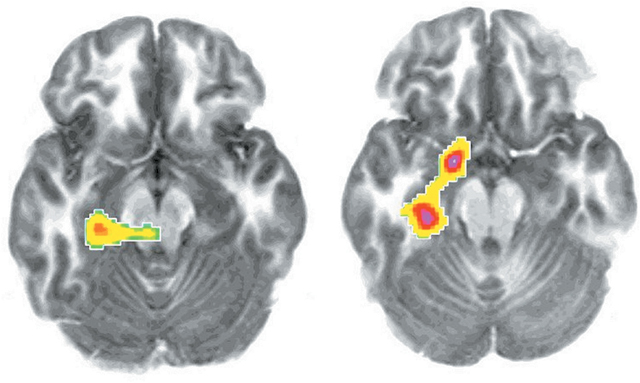

Figure 16.6: The Effects of Medication and Therapy in the Brain PET scans of individuals with social phobia showed similar reductions in activations of the amygdala–

Figure 16.6: The Effects of Medication and Therapy in the Brain PET scans of individuals with social phobia showed similar reductions in activations of the amygdala–From Furmark et al., 2002.

Do therapy and medications work through similar mechanisms?

Given that both therapy and medications are effective, one question is whether they work through similar mechanisms. A study of people with social phobia examined patterns of cerebral blood flow following treatment using either citalopram (an SSRI) or CBT (Furmark et al., 2002). Participants in both groups were alerted to the possibility that they would soon have to speak in public. In both groups, those who responded to treatment showed similar reductions in activation in the amygdala, hippocampus, and neighbouring cortical areas during this challenge (see FIGURE 16.6). The amygdala, located next to the hippocampus (see Figure 6.18) plays a significant role in memory for emotional information. These findings suggest that both therapy and medication affect the brain in regions associated with a reaction to threat. Although it might seem that events that influence the brain should be physical—

One complication in combining medication and psychotherapy is that these treatments are often provided by different people. Psychiatrists are trained in the administration of medication in medical school (and they may also provide psychological treatment), whereas psychologists provide psychological treatment but not medication. This means that the coordination of treatment often requires cooperation between psychologists and psychiatrists.

The question of whether psychologists should be licensed to prescribe medications has been a source of debate among psychologists and physicians (Fox et al., 2009). Opponents argue that psychologists do not have the medical training to understand how medications interact with other drugs. Proponents of prescription privileges argue that patient safety would not be compromised as long as rigorous training procedures were established. This issue remains a focus of debate, and at present, the coordination of medication and psychological treatment usually involves a team effort of psychiatry and psychology.

16.3.6 Biological Treatments beyond Medication

Medication can be an effective biological treatment, but for some people medications do not work or side effects are intolerable. If this group of people does not respond to psychotherapy either, what other options do they have to achieve symptom relief? Some additional avenues of help are available, but some are risky or poorly understood.

Where do people turn if psychological treatment and medication are unsuccessful?

One commonly used biological treatment for severe mental disorders is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), sometimes referred to as shock therapy, which is a treatment that involves inducing a brief seizure by delivering an electrical shock to the brain. The shock is applied to the person’s scalp for less than a second. ECT is primarily used to treat severe depression that has not responded to antidepressant medications, although it may also be useful for treating bipolar disorder (Khalid et al., 2008; Poon et al., 2012). Patients are pretreated with muscle relaxants and are under general anesthetic, so they are not conscious of the procedure. The main side effect of ECT is impaired short-

Another biological approach that does not involve medication is transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a treatment that involves placing a powerful pulsed magnet over a person’s scalp, which alters neuronal activity in the brain. As a treatment for depression, the magnet is placed just above the right or left eyebrow in an effort to stimulate the right or left prefrontal cortex (areas of the brain implicated in depression). TMS is an exciting development because it is noninvasive and has fewer side effects than ECT (see the Neuroscience and Behaviour chapter). Side effects are minimal; they include mild headache and a small risk of seizure, but TMS has no impact on memory or concentration. TMS may be particularly useful in treating depression that is unresponsive to medication (Avery et al., 2009). In fact, a study comparing TMS to ECT found that both procedures were effective, with no significant differences between them (Janicak et al., 2002). Other studies have found that TMS can also be used to treat auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia (Aleman, Sommer, & Kahn, 2007).

Phototherapy, a therapy that involves repeated exposure to bright light, may be helpful to people who have a seasonal pattern to their depression. This could include people suffering with seasonal affective disorder (SAD) (see the Psychological Disorders chapter), or those who experience depression only in the winter months due to the lack of sunlight. Typically, people are exposed to bright light in the morning, using a lamp designed for this purpose. Phototherapy has not been as well researched as psychological treatment or medication, but the handful of studies available suggest it is approximately as effective as antidepressant medication in the treatment of SAD (Thaler et al., 2011).

In very rare cases, psychosurgery, the surgical destruction of specific brain areas, may be used to treat psychological disorders. Psychosurgery has a controversial history, beginning in the 1930s with the invention of the lobotomy by Portuguese physician Egas Moniz (1874–

Psychosurgery is rarely used these days and is reserved only for extremely severe cases for which no other interventions have been effective and the symptoms of the disorder are intolerable to the patient. For instance, psychosurgery is sometimes used in severe cases of OCD in which the person is completely unable to function in their daily life and psychological treatment and medication are not effective. In contrast to the earlier days of lobotomy in which broad regions of brain tissue were destroyed, modern psychosurgery involves a very precise destruction of brain tissue in order to disrupt the brain circuits known to be involved in the generation of obsessions and compulsions. This increased precision has produced better results. For example, people suffering from OCD who fail to respond to treatment (including several trials of medications and cognitive behavioural treatment) may benefit from specific surgical procedures called cingulotomy and anterior capsulotomy. Cingulotomy involves destroying part of the corpus callosum (see Figure 3.18) and cingulate gyrus (the ridge just above the corpus collosum). Anterior capsulotomy involves creating small lesions to disrupt the pathway between the caudate nucleus and putamen. Because of the relatively small number of cases of psychosurgery, there are not as many studies of these techniques as there are for other treatments; however, available studies have shown that psychosurgery typically leads to substantial improvements in both the short and long term for people with severe OCD (Csigó et al., 2010; van Vliet et al., 2013).

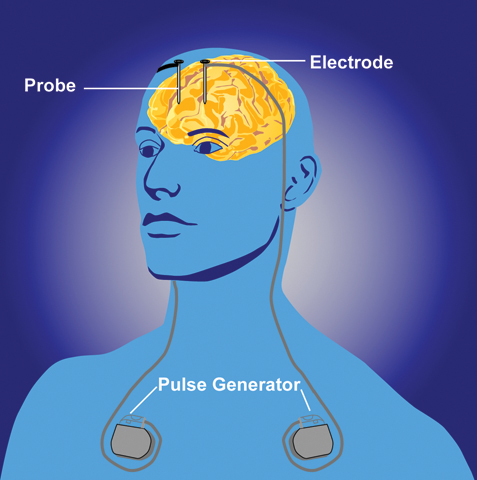

A final approach, called deep brain stimulation (DBS), combines the use of psychosurgery with the use of electrical currents (as in ECT and TMS). In DBS, a treatment pioneered only recently, a small, battery-

Medications have been developed to treat many psychological disorders, including antipsychotic medications (used to treat schizophrenia and psychotic disorders), anti-

anxiety medications (used to treat anxiety disorders), and antidepressants (used to treat depression and related disorders). Medications are often combined with psychotherapy.

Other biomedical treatments include electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and psychosurgery—

this last used in extreme cases, when other methods of treatment have been exhausted.