13.4 The Psychology of Illness: Mind over Matter

One of the mind’s main influences on the body’s health and illness is the mind’s sensitivity to bodily symptoms. Noticing what is wrong with the body can be helpful when it motivates a search for treatment, but sensitivity can also lead to further problems when it snowballs into a preoccupation with illness that itself can cause harm.

Psychological Effects of Illness

Why does it feel so bad to be sick? You notice scratchiness in your throat or the start of sniffles, and you think you might be coming down with something. And in just a few short hours, you’re achy all over, energy gone, no appetite, feverish, feeling dull and listless. You’re sick. The question is, why does it have to be like this? As long as you’re going to have to stay at home and miss out on things anyway, couldn’t sickness be less of a pain?

What is the benefit of the sickness response?

Sickness makes you miserable for good reason. Misery is part of the sickness response, a coordinated, adaptive set of reactions to illness organized by the brain (Hart, 1988; Watkins & Maier, 2005). Feeling sick keeps you home, where you’ll spread germs to fewer people. More important, the sickness response makes you withdraw from activity and lie still, conserving the energy for fighting illness that you’d normally expend on other behavior. Appetite loss is similarly helpful: The energy spent on digestion is conserved. Thus, the behavioral changes that accompany illness are not random side effects; they help the body fight disease.

428

How does the brain know it should do this? The immune response to an infection begins with the activation of white blood cells that “eat” microbes and also release cytokines, proteins that circulate through the body (Maier & Watkins, 1998). Cytokines do not enter the brain, but they activate the vagus nerve that runs from the intestines, stomach, and chest to the brain carrying the “I am infected” message (Goehler et al., 2000). Perhaps this is why we often feel sickness in the “gut,” a gnawing discomfort in the very center of the body.

Interestingly, the sickness response can be prompted without any infection at all, merely by the introduction of stress. The stressful presence of a predator’s odor, for instance, can produce the sickness response of lethargy in an animal, along with symptoms of infection such as fever and increased white blood cell count (Maier & Watkins, 2000). In humans, the connection between sickness response, immune reaction, and stress is illustrated in depression, a condition in which all the sickness machinery runs at full speed. So, in addition to fatigue and malaise, depressed people show signs characteristic of infection, including high levels of cytokines circulating in the blood (Maes, 1995). Just as illness can make you feel a bit depressed, severe depression seems to recruit the brain’s sickness response and make you feel ill (Watkins & Maier, 2005).

Recognizing Illness and Seeking Treatment

You probably weren’t thinking about your breathing a minute ago, but now that you’re reading this sentence, you notice it. Sometimes, we are very attentive to our bodies. At other times, the body seems to be on “automatic,” running along unnoticed until specific symptoms announce themselves or are pointed out by an annoying textbook writer.

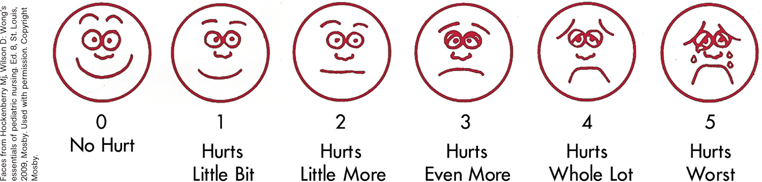

People differ substantially in the degree to which they attend to and report bodily symptoms. People who report many physical symptoms tend to be negative in other ways as well, describing themselves as anxious, depressed, and under stress (Watson & Pennebaker, 1989). Do people with many symptom complaints truly have a lot of problems, or are they just high-

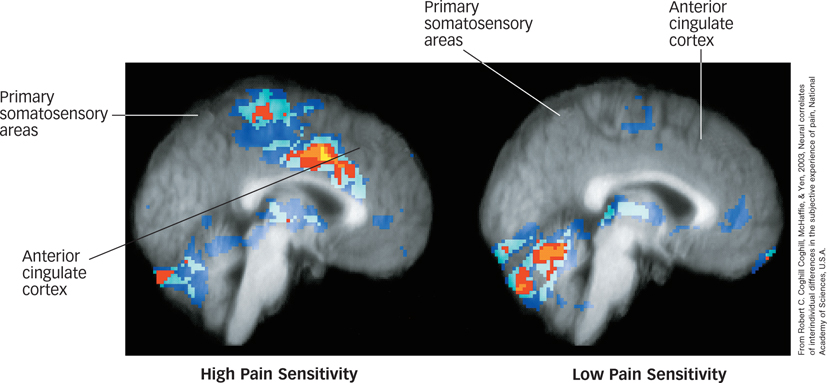

What is the relationship between pain and activity in the brain?

In contrast to complainers are those who underreport symptoms and pain or ignore or deny the possibility that they are sick. Insensitivity to symptoms comes with costs: It can delay the search for treatment, sometimes with serious repercussions. Of 2,404 patients in one study who had been treated for a heart attack, 40% had delayed going to the hospital for over 6 hours from the time they first noticed suspicious symptoms (Gurwitz et al., 1997). These people often waited, just hoping the problem would go away, which is not a good idea because many of the treatments that can reduce the damage of a heart attack are most useful when provided early. When it comes to your own health, protecting your mind from distress through the denial of illness can result in exposing your body to great danger.

429

Somatic Symptom Disorders

How can hypersensitivity to symptoms undermine health?

The flip side of denial is excessive sensitivity to illness, and it turns out that sensitivity also has its perils. Indeed, hypersensitivity to symptoms or to the possibility of illness underlies a variety of psychological problems and can also undermine physical health. Psychologists studying psychosomatic illness, an interaction between mind and body that can produce illness, explore ways in which mind (psyche) can influence body (soma) and vice versa. The study of mind–

psychosomatic illness

An interaction between mind and body that can produce illness.

somatic symptom disorders

The set of psychological disorders in which a person with at least one bodily symptom displays significant health-

sick role

A socially recognized set of rights and obligations linked with illness.

On Being a Patient

Getting sick is more than a change in physical state: It can involve a transformation of identity. This change can be particularly profound with a serious illness: A kind of cloud settles over you, a feeling that you are now different, and this transformation can influence everything you feel and do in this new world of illness. You even take on a new role in life, a sick role: a socially recognized set of rights and obligations linked with illness (Parsons, 1975). The sick person is absolved of responsibility for many everyday obligations and enjoys exemption from normal activities. For example, in addition to skipping school and homework and staying on the couch all day, a sick child can watch TV and avoid eating anything unpleasant at dinner. In return for these exemptions, the sick role also incurs obligations. The properly “sick” individual cannot appear to enjoy the illness or reveal signs of wanting to be sick and must also take care to pursue treatment to end this “undesirable” condition.

What benefits might come from being ill?

Some people feign medical or psychological symptoms to achieve something they want, a type of behavior called malingering. Because many symptoms of illness cannot be faked, malingering is possible only with a restricted number of illnesses. Faking illness is suspected when the secondary gains of illness, such as the ability to rest, to be freed from performing unpleasant tasks, or to be helped by others, outweigh the costs. Such gains can be very subtle, as when a child stays in bed because of the comfort provided by an otherwise distant parent, or they can be obvious, as when insurance benefits turn out to be a cash award for Best Actor. For this reason, malingering can be difficult to diagnose and treat (Feldman, 2004).

430

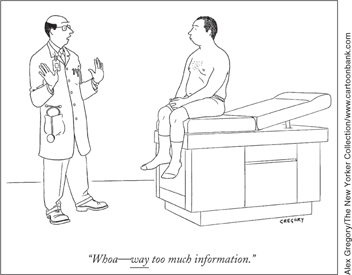

Patient–Practitioner Interaction

Medical care usually occurs through a strange interaction. On one side is a patient, often miserable, who expects to be questioned and examined and possibly prodded, pained, or given bad news. On the other side is a health care provider, who hopes to quickly obtain information from the patient by asking lots of extremely personal questions (and examining extremely personal parts of the body); identify the problem and potential solution; help in some way; and achieve all of this as efficiently as possible because more patients are waiting. It seems less like a time for healing than an occasion for major awkwardness. One of the keys to an effective medical care interaction is physician empathy (Spiro et al., 1994). To offer successful treatment, the clinician must simultaneously understand the patient’s physical state and psychological state. Physicians often err on the side of failing to acknowledge patients’ emotions, focusing instead on technical issues of the case (Suchman et al., 1997). This is particularly unfortunate because a substantial percentage of patients who seek medical care do so for treatment of psychological and emotional problems (Taylor, 1986). The best physician treats the patient’s mind as well as the patient’s body.

Why is it important that a physician express empathy?

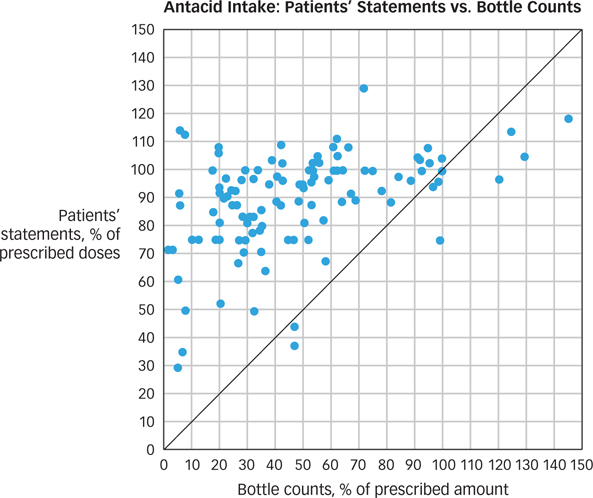

Another important part of the medical care interaction is motivating the patient to follow the prescribed regimen of care (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). When researchers check compliance by counting the pills remaining in a patient’s bottle after a prescription has been underway, they find that patients often do an astonishingly poor job of following doctors’ orders (see FIGURE 13.5). Compliance deteriorates when the treatment must be frequent, as when eyedrops for glaucoma are required every few hours, or inconvenient or painful, such as drawing blood or performing injections in managing diabetes. Finally, compliance decreases as the number of treatments increases. This is a worrisome problem, especially for older patients, who may have difficulty remembering when to take which pill. Failures in medical care may stem from the failure of health care providers to recognize the psychological challenges that are involved in self-

431

SUMMARY QUIZ [13.4]

Question 13.10

| 1. | A person who is preoccupied with minor symptoms and believes they signify a life- |

- cytokines.

- repressive coping.

- burnout.

- a somatic symptom disorder.

d.

Question 13.11

| 2. | Faking an illness is a violation of |

- malingering.

- somatoform disorder.

- the sick role.

- the Type B pattern of behavior.

c.

Question 13.12

| 3. | Which of the following describes a successful health care provider? |

- displays empathy

- pays attention to both the physical and psychological state of the patient

- uses psychology to promote patient compliance

- all of the above

d.