5.1 Conscious and Unconscious: The Mind’s Eye, Open and Closed

What does it feel like to be you right now? It probably feels as though you are somewhere inside your head, looking out at the world through your eyes. You can feel your hands on this book, perhaps, and notice the position of your body or the sounds in the room when you orient yourself toward them. If you shut your eyes, you may be able to imagine things in your mind, even though all the while thoughts and feelings come and go, passing through your imagination. But where are “you,” really? And how is it that this theater of consciousness gives you a view of some things in your world and your mind but not others? The theater in your mind doesn’t have seating for more than one, making it difficult to share what’s on your mental screen with your friends, a researcher, or even yourself in precisely the same way a second time. We’ll look first at the difficulty of studying consciousness directly, then examine the nature of consciousness (what it is that can be seen in this mental theater), and finally explore the unconscious mind (what is not visible to the mind’s eye).

The Mysteries of Consciousness

Other sciences, such as physics, chemistry, and biology, have the great luxury of studying objects, things that we all can see. Psychology studies objects, too, looking at people and their brains and behaviors, but it has the unique challenge of trying to make sense of subjects. A physicist is not concerned with what it is like to be a neutron, but psychologists hope to understand what it is like to be a human; that is, they seek to understand the subjective perspectives of the people whom they study. Psychologists hope to include an understanding of phenomenology, how things seem to the conscious person. Let’s look at two of the more vexing mysteries of consciousness: the problem of other minds and the mind–

phenomenology

How things seem to the conscious person.

The Problem of Other Minds

One great mystery is called the problem of other minds, the fundamental difficulty we have in perceiving the consciousness of others. How do you know that anyone else is conscious? People tell you that they are conscious, of course, and are often willing to describe in depth how they feel, what they are experiencing, and how good or how bad it all is. But perhaps they are just saying these things. There is no clear way to distinguish a conscious person from someone who might do and say all the same things as a conscious person but who is not conscious. Philosophers have called this hypothetical nonconscious person a zombie, in reference to the living-

problem of other minds

The fundamental difficulty we have in perceiving the consciousness of others.

137

Even the consciousness meter used by anesthesiologists falls short. It certainly doesn’t give the anesthesiologist any special insight into what it is like to be the patient on the operating table; it only predicts whether patients will say they were conscious. We simply lack the ability to directly perceive the consciousness of others. In short, you are the only thing in the universe you will ever truly know what it is like to be.

The problem of other minds also means there is no way you can tell if another person’s experience of anything is at all like yours. Although you know what the color red looks like to you, for instance, you cannot know whether it looks the same to other people, or how their experience differs from yours. Of course, most people have come to trust each other in describing their inner lives, reaching the general assumption that other human minds are pretty much like their own. But they don’t know this for a fact, and they can’t know it directly.

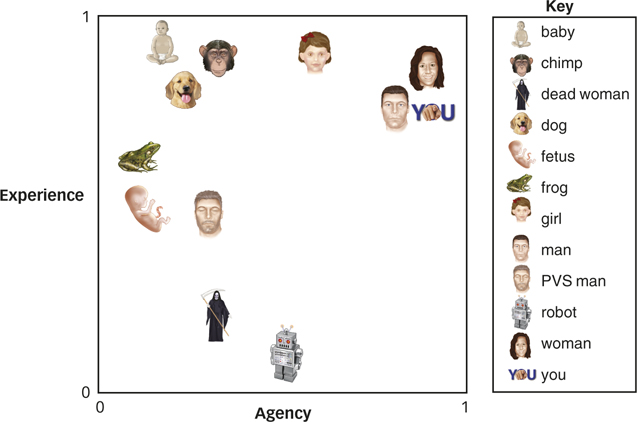

How do people perceive other minds? Researchers conducting a large online survey asked people to compare the minds of 13 different targets, such as a baby, chimp, robot, man, and woman, on 18 different mental capacities, such as feeling pain, pleasure, hunger, and consciousness (Gray, Gray, & Wegner, 2007). Respondents compared pairs of targets: Is a frog or a dog more able to feel pain? Is a baby or a robot more able to feel pain? The researchers found that people judge minds according to two dimensions: the capacity for experience (such as the ability to feel pain, pleasure, hunger, consciousness, anger, or fear) and the capacity for agency (such as the ability for self-

How does the capacity for experience differ from the capacity for agency?

As you’ll remember from the Methods in Psychology chapter, the scientific method requires that any observation made by one scientist should, in principle, be available for observation by any other scientist. But if other minds aren’t observable, how can consciousness be a topic of scientific study? One radical solution is to eliminate consciousness from psychology entirely and follow the other sciences into total objectivity by renouncing the study of anything mental. This was the solution offered by behaviorism, and it turned out to have its own shortcomings, as you saw in the Psychology: Evolution of a Science chapter. Despite the problem of other minds, modern psychology has embraced the study of consciousness. The astonishing richness of mental life simply cannot be ignored.

138

The Mind–Body Problem

Another mystery of consciousness is the mind-body problem, the issue of how the mind is related to the brain and body. French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes (1596–

mind–body problem

The issue of how the mind is related to the brain and body.

But Descartes was right in pointing out the difficulty of reconciling the physical body with the mind. Most psychologists assume that mental events are intimately tied to brain events, such that every thought, perception, or feeling is associated with a particular pattern of activation of neurons in the brain (see the Neuroscience & Behavior chapter). Thinking about a particular person, for instance, occurs with a unique array of neural connections and activations. If the neurons repeat that pattern, then you must be thinking of the same person; conversely, if you think of the person, the brain activity occurs in that pattern.

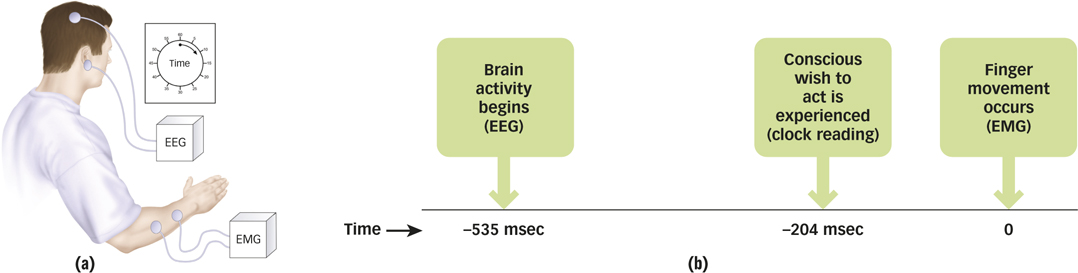

One telling set of studies, however, suggests that the brain’s activities precede the activities of the conscious mind. The electrical activity in the brains of volunteers was measured using sensors placed on their scalps as they repeatedly decided when to move a hand (Libet, 1985). Participants were also asked to indicate exactly when they consciously chose to move by reporting the position of a dot moving rapidly around the face of a clock just at the point of the decision (FIGURE 5.2a). As a rule, the brain begins to show electrical activity around half a second before a voluntary action (535 milliseconds, to be exact). This makes sense because brain activity certainly seems to be necessary to get an action started.

What comes first: brain activity or thinking?

But, as shown in FIGURE 5.2b, the brain also started to show electrical activity before the person reported a conscious decision to move. Although your personal intuition is that you think of an action and then do it, these experiments suggest that your brain is getting started before either the thinking or the doing, preparing the way for both thought and action. Quite simply, it may appear to us that our minds are leading our brains and bodies, but the order of events may be the other way around (Haggard & Tsakiris, 2009; Wegner, 2002).

139

The Nature of Consciousness

How would you describe your own consciousness? Research suggests that consciousness has four basic properties (intentionality, unity, selectivity, and transience), that it occurs on different levels, and that it includes a range of different contents. Let’s examine each of these points in turn.

Four Basic Properties

Researchers have identified four basic properties of consciousness, based on people’s reports of conscious experience.

- Consciousness has intentionality, which is the quality of being directed toward an object. Consciousness is always about something. Despite all the lush detail you see in your mind’s eye, the kaleidoscope of sights and sounds and feelings and thoughts, the object of your consciousness at any one moment is just a small part of all of this (see FIGURE 5.3).

- Consciousness has unity, which is resistance to division. As you read this book, your five senses are taking in a great deal of information. Your eyes are scanning lots of black squiggles on a page (or screen) while also sensing an enormous array of shapes, colors, depths, and textures in your periphery; your hands are gripping a heavy book (or computer); your butt and feet may sense pressure from gravity pulling you against a chair or floor; and you may be listening to music or talking in another room, while smelling the odor of your roommate’s dirty laundry. Your brain—

amazingly— integrates all of this information into the experience of one unified consciousness. - Consciousness has selectivity, the capacity to include some objects but not others. While binding the many sensations around you into a coherent whole, your mind must make decisions about which pieces of information to include—

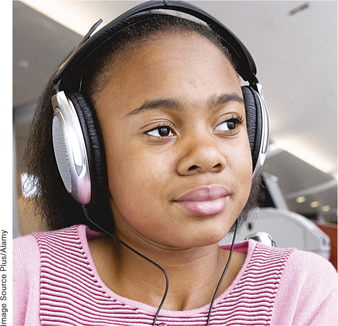

and which to exclude. For example, in what has come to be known as the cocktail-party phenomenon, people tune in one message even while they filter out others nearby. In dichotic listening situation tests, in which people wearing headphones hear different messages in each ear, participants directed to pay attention to messages in one ear are especially likely to notice if their own name is spoken into the unattended ear (Moray, 1959). Perhaps you, too, have noticed how abruptly your attention is diverted from whatever conversation you are having when someone else within earshot at the party mentions your name. What are the properties of consciousness that are involved in integrating lots of information and filtering some out?

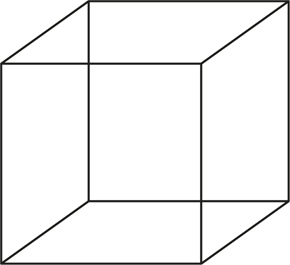

- Consciousness has transience, or the tendency to change. The mind wanders not just sometimes, but incessantly, from one “right now” to the next “right now” and then on to the next (Wegner, 1997). William James, whom you met way back in the Psychology: Evolution of a Science chapter, famously described consciousness as a “stream” (James, 1890). The stream of consciousness may flow in this way partly because of the limited capacity of the conscious mind. We humans can hold only so much information in our minds at any one moment, so when more information is selected, some of what is currently there must disappear. As a result, our focus of attention keeps changing. The stream of consciousness flows so inevitably that it even changes our perspective when we view a constant object like a Necker cube (see FIGURE 5.4).

140

cocktail-party phenomenon

A phenomenon in which people tune in one message even while they filter out others nearby.

dichotic listening

A task in which people wearing headphones hear different messages presented to each ear.

Levels of Consciousness

Consciousness can also be understood as having levels. The levels of consciousness are not a matter of degree of overall brain activity, and so they would probably all register as “conscious” on that wakefulness meter for surgery patients you read about at the beginning of the chapter. Instead, the levels of consciousness involve different qualities of awareness of the world and of the self.

- Minimal consciousness is a low-

level kind of sensory awareness and responsiveness that occurs when the mind inputs sensations and may output behavior (Armstrong, 1980). This kind of sensory awareness and responsiveness could even happen when someone pokes you during sleep and you turn over. Something seems to register in your mind, at least in the sense that you experience it, but you may not think at all about having had the experience. It could be that animals or, for that matter, even plants can have this minimal level of consciousness. But because of the problem of other minds and the notorious reluctance of animals and plants to talk to us, we can’t know for sure that they experience the things that make them respond.What aspect of full consciousness distinguishes it from minimal consciousness?

- Full consciousness occurs when you know and are able to report your mental state. Being fully conscious means that you are aware of having a mental state while you are experiencing the mental state itself. When you have a hurt leg and mindlessly rub it, for instance, your pain may be minimally conscious. It is only when you realize that your leg hurts, though, that the pain becomes fully conscious. Have you ever been driving a car and suddenly realized that you don’t remember the past 15 minutes of driving? Chances are that you were not unconscious but were instead minimally conscious. When you are completely aware and thinking about your driving, you have moved into the realm of full consciousness. Full consciousness involves not only thinking about things but also thinking about the fact that you are thinking about things (Jaynes, 1976; see the Hot Science box).

When do people go out of their way to avoid mirrors?

- Self-consciousness is yet another distinct level of consciousness in which the person’s attention is drawn to the self as an object (Morin, 2006). Most people report experiencing such self-

consciousness when they are embarrassed; when they find themselves the focus of attention in a group; when someone focuses a camera on them; or when they are deeply introspective about their thoughts, feelings, or personal qualities. Looking in a mirror, for example, is all it takes to make people evaluate themselves— thinking not just about their looks, but also about whether they are good or bad in other ways. People go out of their way to avoid mirrors when they’ve done something they are ashamed of (Duval & Wicklund, 1972). However, because it makes people self- critical, the self- consciousness that results when people see their own mirror images can make them briefly more helpful, more cooperative, and less aggressive (Gibbons, 1990).

self-consciousness

A distinct level of consciousness in which the person’s attention is drawn to the self as an object.

minimal consciousness

A low-

full consciousness

Consciousness in which you know and are able to report your mental state.

141

Hot Science: The Mind Wanders

The Mind Wanders

Yes, the mind wanders. You’ve no doubt had experiences of reading and suddenly realizing that you have not even been processing what you’ve read. Even while your eyes are dutifully following the lines of print, at some point, you begin to think about something else—

Mind wandering, or the experience of “stimulus-

Learning about the connection between mind wandering and unhappiness might lead you to feel … unhappy. But as it turns out, mind wandering may also have its benefits. For thousands of years, some of the world’s greatest thinkers have noted that their most important breakthroughs came during periods of daydreaming or mind wandering. For instance, Einstein is said to have made major breakthroughs in his relativity theory while going for a walk (rather than sitting at his desk). In one recent study, participants completed a creative problem-

Most animals don’t appear to have self-

142

Conscious Contents

What’s on your mind? For that matter, what’s on everybody’s mind? One way to learn what is on people’s minds is to ask them, and much research has called on people simply to think aloud. A more systematic approach is the experience-

How do researchers study subjective experience?

Experience-

|

Current Concern Category |

Example |

Frequency of Students Who Mentioned the Concern |

|---|---|---|

|

Family |

Gain better relations with immediate family |

40% |

|

Roommate |

Change attitude or behavior of roommate |

29% |

|

Household |

Clean room |

52% |

|

Friends |

Make new friends |

42% |

|

Dating |

Desire to date a certain person |

24% |

|

Sexual intimacy |

Abstaining from sex |

16% |

|

Health |

Diet and exercise |

85% |

|

Employment |

Get a summer job |

33% |

|

Education |

Go to graduate school |

43% |

|

Social activities |

Gain acceptance into a campus organization |

34% |

|

Religious |

Attend church more |

51% |

|

Financial |

Pay rent or bills |

8% |

|

Government |

Change government policy |

14% |

|

Source: Information from Goetzman, E.S., Hughes, T., & Klinger, E., 1994. |

||

What part of the brain is active during daydreaming?

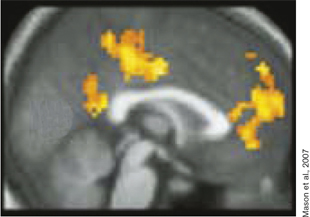

Although current concerns often dominate our thoughts, we also sometimes experience daydreaming, a state of consciousness in which a seemingly purposeless flow of thoughts comes to mind. The brain, however, is active even when there is no specific task at hand. Daydreaming was examined in an fMRI study of people resting in the scanner (Mason et al., 2007). Usually, people in brain-

143

The current concerns that populate consciousness can sometimes get the upper hand, transforming daydreams or everyday thoughts into rumination and worry. When this happens, people may exert mental control, the attempt to change conscious states of mind. For example, someone troubled by a recurring worry about the future (“What if I can’t get a decent job when I graduate?”) might choose to try not to think about this because it causes too much anxiety and uncertainty. Whenever this thought comes to mind, the person engages in thought suppression, the conscious avoidance of a thought. This may seem like a perfectly sensible strategy because it eliminates the worry and allows the person to move on to think about something else.

mental control

The attempt to change conscious states of mind.

thought suppression

The conscious avoidance of a thought.

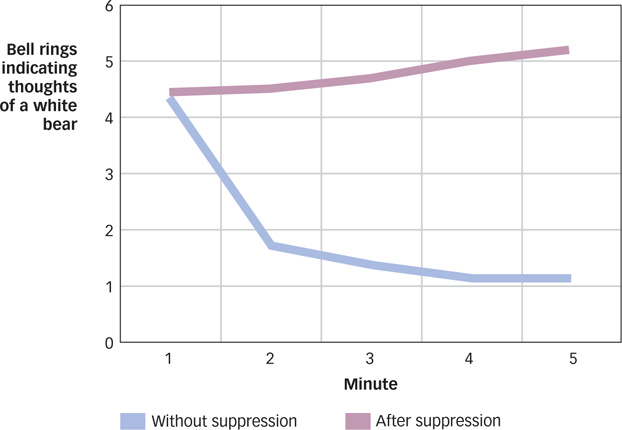

Or does it? Daniel Wegner and his colleagues (1987) asked research participants to try not to think about a white bear for 5 minutes while they recorded each participant’s thoughts aloud into a tape recorder. In addition, participants were asked to ring a bell if the thought of a white bear came to mind. On average, they mentioned the white bear or rang the bell (indicating the thought) more than once per minute. Thought suppression simply didn’t work and instead produced a flurry of returns of the unwanted thought. What’s more, when research participants were later asked to deliberately think about a white bear, they became oddly preoccupied with it. A graph of their bell rings in FIGURE 5.6 shows that these participants had the white bear come to mind far more often than did people who had only been asked to think about the bear from the outset, with no prior suppression. This rebound effect of thought suppression, the tendency of a thought to return to consciousness with greater frequency following suppression, suggests that the act of trying to suppress a thought may itself cause that thought to return to consciousness in a robust way.

rebound effect of thought suppression

The tendency of a thought to return to consciousness with greater frequency following suppression.

144

Is consciously avoiding a worrisome thought an effective strategy?

How ironic: Trying to consciously achieve one task may produce precisely the opposite outcome! These ironic effects seem most likely to occur when the person is distracted or under stress. People who are distracted while they are trying to get into a good mood, for example, tend to become sad (Wegner, Erber, & Zanakos, 1993), and those who are distracted while trying to relax actually become more anxious than those who are not trying to relax (Wegner, Broome, & Blumberg, 1997). Likewise, an attempt not to overshoot a golf putt, undertaken during distraction, often yields the unwanted overshot (Wegner, Ansfield, & Pilloff, 1998). The theory of ironic processes of mental control proposes that such ironic errors occur because the mental process that monitors errors can itself produce them (Wegner, 1994a, 2009). In the attempt not to think of a white bear, for instance, a small part of the mind is ironically searching for the white bear. As this unconscious monitoring whirs along in the background, it unfortunately increases the person’s sensitivity to the very thought that is unwanted. Ironic processes are needed for effective mental control—

ironic processes of mental control

Mental processes that can produce ironic errors because monitoring for errors can itself produce them.

The Unconscious Mind

Many other mental processes are unconscious, too, in the sense that they occur without our experience of them. For example, think for a moment about the mental processes involved in simple addition. What happens in consciousness between hearing a problem (what’s 4 + 5?) and thinking of the answer (9)? It may feel like nothing happens—

Freudian Unconscious

As you read in the Psychology: Evolution of a Science chapter, Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory viewed conscious thought as the surface of a much deeper mind made up of unconscious processes. Far more than just a collection of hidden processes, Freud described a dynamic unconscious—an active system encompassing a lifetime of hidden memories, the person’s deepest instincts and desires, and the person’s inner struggle to control these forces. The dynamic unconscious might contain hidden sexual thoughts about one’s parents, for example, or destructive urges aimed at a helpless infant—

dynamic unconscious

An active system encompassing a lifetime of hidden memories, the person’s deepest instincts and desires, and the person’s inner struggle to control these forces.

repression

A mental process that removes unacceptable thoughts and memories from consciousness and keeps them in the unconscious.

145

What might Freudian slips tell us about the unconscious mind?

Freud looked for evidence of the unconscious mind in speech errors and lapses of consciousness, or what are commonly called Freudian slips. Forgetting the name of someone you dislike, for example, is a slip that seems to have special meaning. Freud believed that errors are not random and instead have some surplus meaning that has been created by an intelligent unconscious mind, even though the person consciously disavows the thoughts and memories that caused the errors in the first place. For example, when reporting on the news that members of the U.S. military had killed Osama bin Laden, several reporters and commentators at Fox News, a conservative news outlet, independently reported that Obama bin Laden was dead. Did the Fox News slip mean anything? Many of the meaningful errors Freud attributed to the dynamic unconscious were not predicted in advance and so seem to depend on clever after-

A Modern View of the Cognitive Unconscious

How can unconscious processes be measured?

Modern psychologists share Freud’s interest in the impact of unconscious mental processes on consciousness and on behavior. However, rather than Freud’s vision of the unconscious as a teeming menagerie of animal urges and repressed thoughts, the current study of the unconscious mind views it as the factory that builds the products of conscious thought and behavior (Kihlstrom, 1987; Wilson, 2002). The cognitive unconscious includes all the mental processes that give rise to a person’s thoughts, choices, emotions, and behavior even though they are not experienced by the person.

cognitive unconscious

All the mental processes that give rise to a person’s thoughts, choices, emotions, and behavior even though they are not experienced by the person.

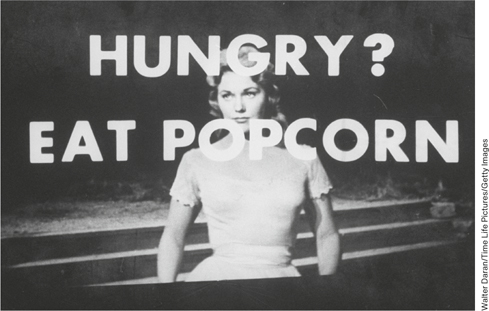

One indication of the cognitive unconscious at work is when a person’s thoughts or behaviors are changed by exposure to information outside of consciousness. This happens in subliminal perception, when thought or behavior is influenced by stimuli that a person cannot consciously report perceiving. Worries about the potential of subliminal influence were first provoked in 1957, when a marketer claimed he had increased concession sales at a movie theater by flashing the words “Eat Popcorn” and “Drink Coke” briefly on-

subliminal perception

Thought or behavior that is influenced by stimuli that a person cannot consciously report perceiving.

Although the story above was a hoax, factors outside our conscious awareness can indeed influence our behavior. For example, one classic study had college students complete a survey that called for them to make sentences with various words (Bargh, Chen, & Burrows, 1996). The students were not informed that most of the words were commonly associated with aging (Florida, gray, wrinkled), and even afterward they didn’t report being aware of this trend. In this case, the “aging” idea wasn’t presented subliminally; instead, it was just not very noticeably presented. As these research participants left the experiment, they were clocked as they walked down the hall. Compared with those not exposed to the aging-

146

SUMMARY QUIZ [5.1]

Question 5.1

| 1. | Which of the following is NOT a basic property of consciousness? |

- intentionality

- disunity

- selectivity

- transience

b.

Question 5.2

| 2. | Currently, unconscious processes are understood as |

- a concentrated pattern of thought suppression.

- a hidden system of memories, instincts, and desires.

- a blank slate.

- unexperienced mental processes that give rise to thoughts and behavior.

d.

Question 5.3

| 3. | The _____________ unconscious is at work when subliminal and unconscious processes influence thought and behavior. |

- minimal

- repressive

- dynamic

- cognitive

d.