Roots, Schools, and Perspectives of Psychology

The field of psychology is a little over 130 years old, very young compared to other scientific disciplines, but its core questions are as old as humanity itself. Look at the works of the ancient Greeks, and you will see that they asked some of the same questions as modern psychologists—questions such as, What is the connection between the body and mind? How do we obtain knowledge? Where does knowledge reside? Making your way through this book, you will see answers to these questions take many forms.

Philosophy and Physiology

LO 4 Identify influential people in the formation of psychology as a discipline.

The roots of psychology lie in disciplines as diverse as philosophy and physiology. In ancient Greece, the great philosopher Plato (427–347 BCE) believed that truth and knowledge exist in the soul before birth, that is, humans are born with some degree of innate knowledge. Plato raised an important issue psychologists still contemplate: the contribution of nature in the human capacity for cognition.

One of Plato’s most renowned students, Aristotle (384–322 BCE), eventually went on to challenge his mentor’s basic teachings. Aristotle believed that we know reality through our perceptions, and we learn through our sensory experiences, an approach now commonly referred to as empiricism. Aristotle has been credited with laying the foundation for a scientific approach to answering questions, including those pertaining to psychological concepts such as emotion, sensation, and perception (Slife, 1990; Thorne & Henley, 2005). Ultimately, because he believed knowledge is the result of our experiences, Aristotle paved the way for scientists to study the world through their observations.

This notion that experience (or nurture) plays an all-important role in how we acquire knowledge contradicts Plato’s belief that it is inborn (the result of nature). Aristotle thus provided the opposing position in the discussion of the relative contributions of nature and nurture, a central theme in the field of psychology. Today, psychologists agree that nature and nurture both play important roles, and current research explores the contribution of each through studies of heredity and environmental factors.

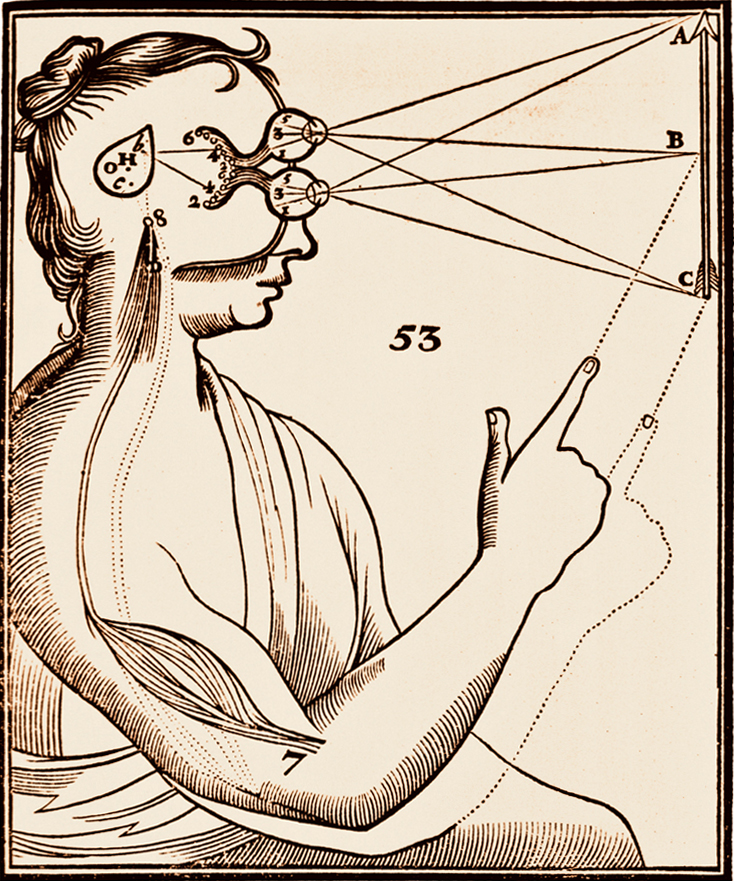

If Aristotle placed great confidence in human perception, French philosopher René Descartes (dā-′kärt; 1596–1650) practically discounted it. Famous for saying, “I think, therefore, I am,” Descartes believed that most everything else was uncertain, including what he saw with his own eyes. He proposed that the body is like a tangible machine, and the mind has no physical substance. The body and mind interact as two separate entities, a view known as dualism, and Descartes (and many others) wondered how they were connected. Descartes’ work allowed for a more scientific approach to examining thoughts, emotions, and other topics previously believed to be beyond the scope of study.

About 200 years later, another scientist experienced a “flash of insight” about the mind–body connection. It was October 22, 1850, when German physicist Gustav Theodor Fechner (1801–1887) suddenly realized that he could “solve” the mind–body conundrum, that is, figure out how they connect. Fechner reasoned that by studying the physical ability to sense stimuli, we are simultaneously conducting experiments on the mind. In other words, we can understand how the mind and body work together by studying sensation. Fechner is considered one of the founders of physiological psychology, and his efforts laid the groundwork for research on sensation and perception (Benjamin, 2007; Robinson, 2010).

Psychology Is Born

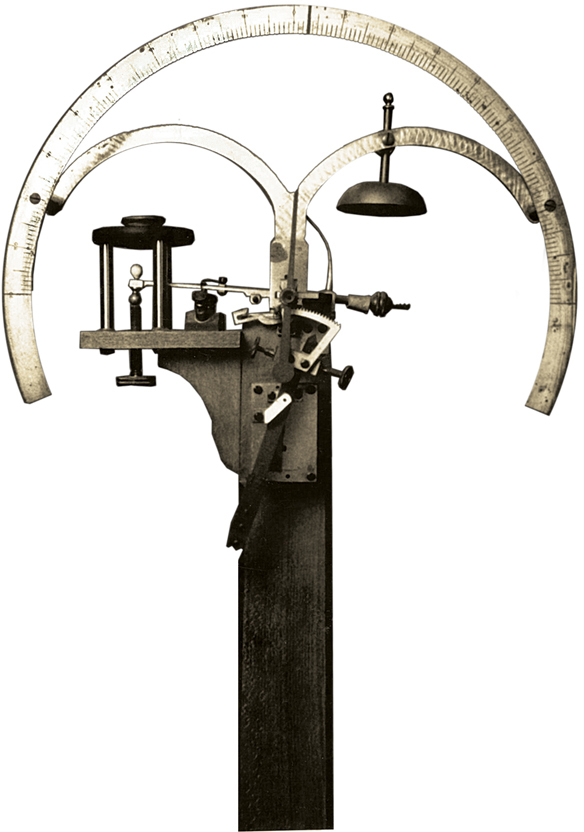

Thus far, the only people in our presentation of the history of psychology have been philosophers and a physicist. You might ask where all the psychologists were during the time of Descartes and Fechner. The answer is simple: There were no psychologists until 1879. That was the year Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) founded the first psychology laboratory, at the University of Leipzig in Germany, and for this he generally is considered the “father of psychology.” Equipped with its own laboratory and research team, psychology finally became a discipline in its own right. Wundt also created and edited the first psychological journal and published numerous books, including meticulous accounts of his psychological experiments and methods, which provided details of the scientific nature of this new area of study.

The overall aim of Wundt’s early experiments was to measure psychological processes through introspection, a method used to examine one’s own conscious activities. For Wundt, introspection involved effortful reflection on the sensations, feelings, and images experienced in response to a stimulus, followed by reports that were objective, meaning free of opinions, beliefs, expectations, and values. In order to ensure reliable data, Wundt required all his participants to complete 10,000 “introspective observations” prior to starting data collection. His participants were asked to make quantitative judgments about physical stimuli—how strong they were, how long they lasted, and so on (Boring, 1953; Schultz & Schultz, 2012). The following Try This should give you a better sense of Wundt’s method of introspection.

try this

The next time your cell phone vibrates or rings, take the opportunity to engage in some introspection. Grab the cell phone and hold it in your hands (try to resist answering the call). Pay attention to what you experience as you wait for the vibrations to stop. Then put down the phone and consider your experience. Report on your sensations (the color, the shape, the texture, and so on) and feelings (anxiety, excitement, frustration), but make your observations objective.

Structuralism

A student of Wundt’s, Edward Titchener (1867–1927) developed the school of psychology known as structuralism. In 1893 Titchener set up a laboratory at Cornell University (in Ithaca, New York) where he conducted introspection experiments aimed at determining the structure and “atoms” (or most basic elements) of the mind. Titchener’s participants, also extremely well trained, were asked to describe the elements of their current consciousness. In contrast to Wundt’s focus on objective, quantitative reports of conscious experiences, Titchener’s participants provided detailed reports of their subjective (unique or personal) experiences (Hothersall, 2004). The school of structuralism did not last past Titchener’s lifetime, and even most of his contemporaries regarded structuralism as outdated. Nevertheless, Titchener demonstrated that psychological studies could be conducted through observation and measurement.

Functionalism

In the late 1870s, William James (1842–1910) offered the first psychology classes in the United States, at Harvard University, where he was granted $300 for laboratory and classroom demonstration equipment (Croce, 2010). James had little interest in pursuing the experimental psychology practiced by Wundt and other Europeans; instead, he was inspired by the work of Charles Darwin (1809–1882). Studying the elements of introspection was not a worthwhile endeavor, James believed, because consciousness is an ever-changing “stream” of thoughts. Consciousness cannot be studied by looking for fixed or static elements, because they don’t exist, or so he reasoned. But James believed consciousness does serve a function, and it is important to study the purpose of thought processes, feelings, and behaviors, and how they help us adapt to the environment. This focus on purpose and adaptation in psychological research is the overarching theme of the school of functionalism. Although it didn’t endure as a separate field of psychology, functionalism has continued to influence the practice of psychology, as evidenced by educational psychology, studies of emotion, and comparative studies of animal behavior (Benjamin, 2007).

Here Come the Women

Like most sciences, psychology began as a “boys’ club,” with men earning the degrees, teaching the classes, and running the labs. There were, however, a few women, as competent and inquiring as their male counterparts, who beat down the club doors long before women were formally invited. One of William James’s students, Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930), completed all the requirements for a PhD at Harvard, but was not allowed to graduate from the then all-male college because she was a woman. Nonetheless, she persevered with her work and established her own laboratory at Wellesley College, eventually becoming the first female president of the American Psychological Association (APA). If you are wondering, the first woman to actually earn a PhD in psychology was Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939), a student of Titchener’s. Her degree, which was granted in 1894, came from Cornell, which—unlike Harvard—allowed women to earn doctorates at the time.

Mamie Phipps Clark (1917–1983) was the first Black woman to be awarded a PhD in psychology from Columbia University. Her work, which she conducted with her husband Kenneth Bancroft Clark, examined the impact of prejudice and discrimination on child development. In particular, she explored how race recognition impacts a child’s self-esteem (Lal, 2002). Her husband held a faculty position at City University of New York, but she was never allowed to teach there. Instead, she found a job analyzing research data and eventually became executive director of the Northside Center for Child Development in upper Manhattan (Benjamin, 2007).

Thanks to trailblazers such as Calkins, Washburn, and Clark, the field of psychology is no longer dominated by men. In fact, about three quarters of students earning master’s degrees and PhDs in psychology are women, a statistic that now has some experts worrying about the need for more men in various subfields of psychology (Cynkar, 2007).

Psychology’s Perspectives

LO 5 List and summarize the major perspectives in psychology.

Some of the early schools of psychology had a lasting impact and others seemed to fade. Nevertheless, they all contributed to the growth of the young science. To appreciate the vast field of psychology, it is useful to examine the influences of the early schools, and how some developed into perspectives. Each perspective described below provides a unique vantage point for explaining the complex nature of human behavior. Infographic 1.1 shows how the early roots of psychology and the perspectives fused and flow together.

Psychoanalytic

Toward the end of the 19th century, while many early psychologists were busy investigating the “normal” functioning of the mind (in experimental psychology), Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) focused much of his attention on the “abnormal” aspects. Freud believed that behavior and personality are influenced by the conflict between one’s inner desires (such as sexual and aggressive impulses) and the expectations of society—a clash that occurs for the most part unconsciously or outside of awareness (Gay, 1988; Chapter 11). The psychoanalytic perspective is used as an explanatory tool in many of psychology’s subfields.

Behavioral

As Freud worked on his new theories of the unconscious mind, Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936), a Russian scientist, was busy studying canine digestion. A physiologist by training, Pavlov got sidetracked by an intriguing phenomenon. The dogs in his study had learned to salivate in response to stimuli or events in the environment, a type of learning that eventually became known as classical conditioning (Chapter 5). Building on Pavlov’s conditioning experiments, American psychologist John B. Watson (1878–1958) established behaviorism, which viewed psychology as the scientific study of behaviors that could be seen and/or measured. Consciousness, sensations, feelings, and the unconscious were not suitable topics of study, according to Watson.

Carrying on the behaviorist approach to psychology, B. F. Skinner (1904–1990) studied the relationship between behaviors and their consequences. Skinner’s research focused on operant conditioning, a type of learning that occurs when behaviors are rewarded or punished (Chapter 5). Skinner acknowledged that mental processes such as memory and emotion might exist, but they are not topics to be studied in psychology. To ensure that psychology was a science, he insisted on studying behaviors that could be observed and documented.

Humanistic

Psychologists such as Carl Rogers (1902–1987) and Abraham Maslow (1908–1970) took psychology in yet another direction. The founders of humanistic psychology were critical of the deterministic tilt of psychoanalysis and behaviorism, and the presumed lack of control people have over their lives. The humanistic perspective suggests that human nature is essentially positive, and that people are naturally inclined to grow and change for the better (Chapter 11) (Maslow, 1943; Rogers, 1961). Humanism challenged the thinking and practice of researchers and clinicians who had been “raised” on Watson and Skinner. Reflecting on the history of psychology, we cannot help but notice that new developments are often reactions to what came before. The rise of the humanistic perspective was, in some ways, a rebellion against the rigidity of psychoanalysis and behaviorism.

Cognitive

During the two-decade prime of behaviorism (1930–1950), many psychologists only studied observable behavior. Yet prior to behaviorism, psychologists had emphasized the study of thoughts and emotions. The situation eventually came full-circle in the 1950s, when a new force in psychology brought these unobservable elements back into focus. This renewed interest in the study of mental processes falls under the field of cognitive psychology (Wertheimer, 2012). And George Miller’s (1920–2012) research on memory is considered an important catalyst for this cognitive revolution (Chapter 6). The cognitive perspective examines mental processes that direct behavior, focusing on concepts such as thinking, memory, and language. The cognitive neuroscience perspective, in particular, explores physiological explanations for mental processes, searching for connections between behavior and the human nervous system, especially the brain. With the development of brain-scanning technologies, cognitive neuroscience has flourished, interfacing with fields such as medicine, computer science, and psychology.

Evolutionary

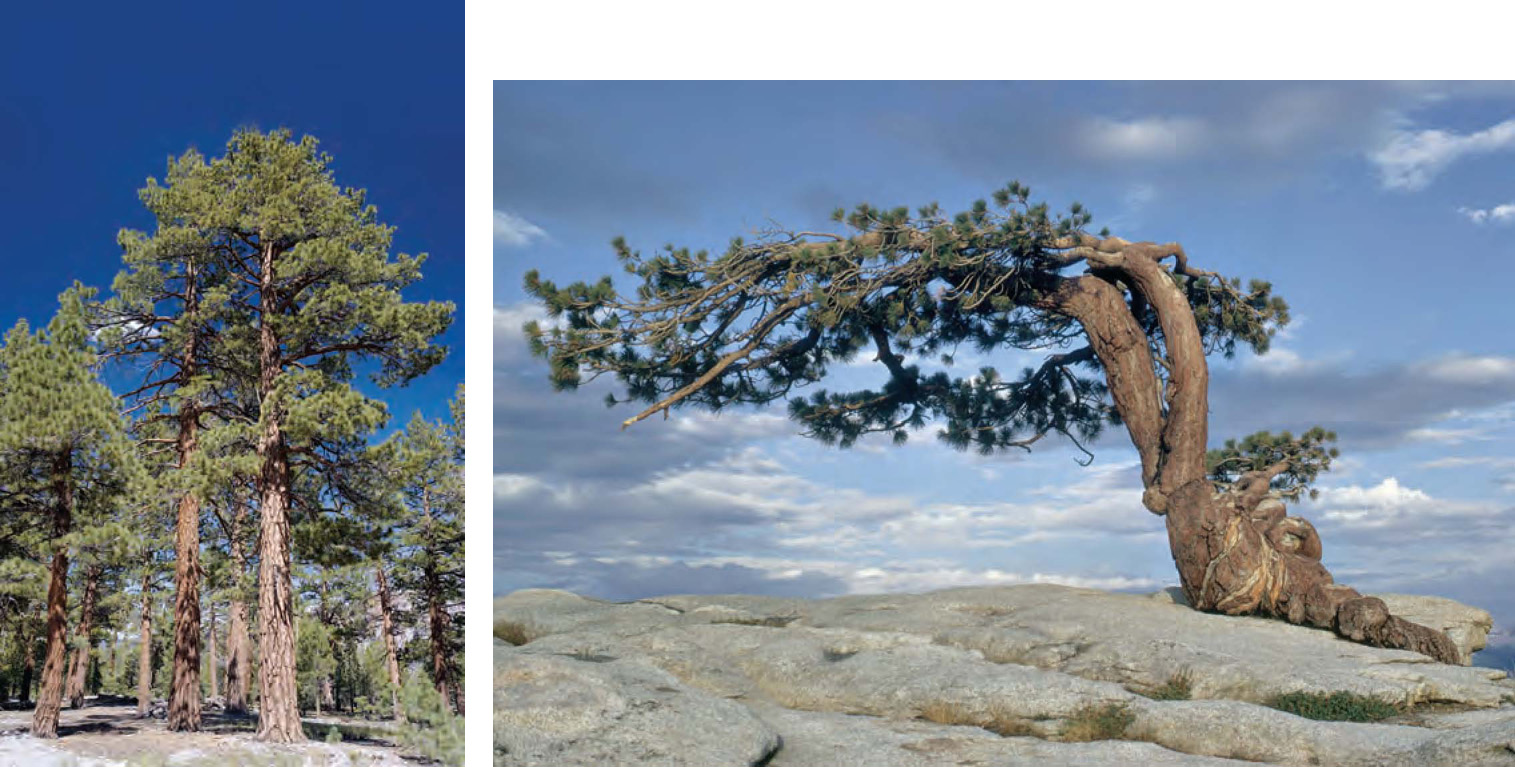

According to the evolutionary perspective, behaviors and mental processes are shaped by the forces of evolution This perspective is based on Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and the principles of natural selection. As Darwin saw it, great variability exists in the characteristics that humans and other organisms exhibit. Natural selection is the process through which inherited traits in a given population either increase in frequency because they are adaptive or decrease in frequency because they are maladaptive. Humans have many adaptive traits and behaviors that appear to have evolved through natural selection.

Biological

The biological perspective uses knowledge about underlying physiology to explain behavior and mental processes. Psychologists who take this approach explore how biological factors, such as hormones, genes, and the brain, are involved in behavior and cognition. Chapter 2 provides a foundation for understanding this perspective.

Sociocultural

The sociocultural perspective suggests that we must examine the influences of social interactions and culture, including the roles we play. Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) proposed that we must examine how social and cultural features in children’s lives influence their cognitive development (Chapter 8). Researchers such as Mamie Phipps Clark study the impact of prejudice, segregation, and discrimination, with the realization that we must consider the importance of sociocultural factors as they relate to the development of the self (Lal, 2002).

In the past, researchers often assumed that the findings of their studies were applicable to people of all ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Then in the 1980s, cross-cultural research began to uncover differences that called into question the presumed universal nature of these findings. New studies revealed that Western research participants are not always representative of people from other cultures. We also must remain aware that groups within a culture can influence behavior and mental processes; thus, we need to take into account these various settings and subcultures.

Biopsychosocial

Many psychologists use the biopsychosocial perspective to explain behavior; in other words, they examine the biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors influencing behavior (Beauchamp & Anderson, 2010). The biopsychosocial perspective suggests that these factors are highly interactive: It’s not just the convergence of factors that matters, but the way they interact.

Summary of Perspectives

You can see that the field of psychology abounds with diversity. With so many perspectives (TABLE 1.3), how do we know which one is the most accurate and effective in achieving psychology’s goals? Human behavior is complex and requires an integrated approach to explain its origins. Sometimes it is also necessary to create a model to help clarify a complex set of observations, as a model frequently allows us to picture in our minds what we seek to understand. Many psychologists pick and choose among theories and models, as needed, to explain and understand behavior. Remember this integrated approach as you learn more about the miners. What biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors were involved in their survival? How did these factors combine to form their overall experience?

INFOGRAPHIC 1.1: Psychology’s Roots

The first laboratory dedicated to the new science of psychology was founded by Wilhelm Wundt at the University of Leipzig in Germany in 1879. But psychology’s roots go back further than that. Philosophers and scientists have long been interested in understanding how the mind works. Early schools of thought like Structuralism and Functionalism developed into contemporary perspectives, each defined by different sets of interests, prompting different kinds of questions.

| Perspective | Main Idea | Questions Psychologists Ask |

| Psychoanalytic | Illustrates the underlying conflicts that influence behavior. | How do our unconscious conflicts affect our decisions and behavior? |

| Behavioral | Explores human behavior as learned primarily through associations, reinforcers, and observation. | How does learning shape our behavior? |

| Humanistic | Focuses on the positive and growth aspects of human nature. | How do choice and self-determination influence behavior? |

| Cognitive | Examines the mental processes that direct behavior. | How do thinking, memory, and language direct behavior? |

| Evolutionary | Examines characteristics in terms of how they influence adaptation to the environment and survival. | How does natural selection advance our behavioral predispositions? |

| Biological | Uses knowledge about underlying physiology to explore and explain behavior and mental processes. | How do biological factors, such as hormones, genes, anatomy, and brain structures, influence behavior and mental processes? |

| Sociocultural | Examines the influences of other people as well as the larger culture to help explain behavior and mental processes. | How do culture and environment shape our attitudes? |

| Biopsychosocial | Investigates the biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors that influence behavior. | How do the interactions of biology, psychology, and culture influence behavior and mental processes? |

| Psychologists draw on a variety of theories in their research and practice. Listed above are the dominant theoretical perspectives, all of which reappear many times in this textbook. Human behaviors are often best understood when viewed through more than one theoretical lens. | ||

THE FIRST 17 DAYS

What took place inside the mine during the first 17 days after the cave-in is not totally clear. The men made a “pact of silence,” promising each other they would never disclose the unpleasant details of that dark period—unless they did so as a group (Gardner & Wade, 2010, October 18). According to miner Juan Illanes, “The first 17 days were a nightmare” (translated from Agence France Presse, 2010, October 15). Immediately following the mine collapse, the men switched to survival mode. When faced with a life-or-death situation, the brain responds by unloading stress hormones. This stress response, which we will discuss in more detail in Chapter 12, leads to a boost of physical energy, alertness, and an overwhelming sense of urgency to deal with a threat. The miners found it difficult to stay calm and think rationally. Some lost their tempers and started to shout. They argued about what to do next: Should they stay in the safety shelter awaiting a rescue team or search the mine for exit routes? The shift foreman Luis Urzúa attempted to take command, but some of the miners refused to recognize his authority. That first night underground, all bets were off. There was no plan, no cooperation. It was every man for himself (Franklin, 2011).

What took place inside the mine during the first 17 days after the cave-in is not totally clear. The men made a “pact of silence,” promising each other they would never disclose the unpleasant details of that dark period—unless they did so as a group (Gardner & Wade, 2010, October 18). According to miner Juan Illanes, “The first 17 days were a nightmare” (translated from Agence France Presse, 2010, October 15). Immediately following the mine collapse, the men switched to survival mode. When faced with a life-or-death situation, the brain responds by unloading stress hormones. This stress response, which we will discuss in more detail in Chapter 12, leads to a boost of physical energy, alertness, and an overwhelming sense of urgency to deal with a threat. The miners found it difficult to stay calm and think rationally. Some lost their tempers and started to shout. They argued about what to do next: Should they stay in the safety shelter awaiting a rescue team or search the mine for exit routes? The shift foreman Luis Urzúa attempted to take command, but some of the miners refused to recognize his authority. That first night underground, all bets were off. There was no plan, no cooperation. It was every man for himself (Franklin, 2011).

After a sleepless night on the wet floor, the men arose in darkness (morning, noon, and midnight all look the same when you’re half a mile beneath the earth’s surface). But the day started off on a bright note when one of the older miners, José Henríquez, led the group in a prayer. With restored optimism, one group of men began to search the mine’s winding tunnels for escape passages. Another team tried to alert rescue workers by blasting through rock with dynamite sticks, banging the roof with heavy machinery, and beeping the horns of trucks that had been sealed underground with them. Both missions failed, and the miners spent yet another night splayed on jagged slabs of rock (Franklin, 2011).

Several days passed without a sign from the world above, and the miners grew weak and weary. To stretch their food supply over several days, they had been forced to limit their intake to one spoonful of tuna fish, half a glass of milk, and one cracker every 24 hours—about 100 calories per day. Their only source of hydration was oil-tainted water so foul-tasting that one man opted to try his own urine as an alternative. For a toilet, they used an old oil drum, the smell of which was almost unbearable (Franklin, 2011).

At the 2-week mark, the food supply had been reduced to two cans of tuna fish (Franklin, 2011). “Our bodies were eating away at themselves,” miner Richard Villarroel told journalists (translated from El Mercurio, 2010, October 15). Although they heard drills humming for several days, a sure sign that a recovery effort was under way, no rescue team had actually reached the part of the mine where they were trapped. Time was not on their side (Franklin, 2011).

By Day 16, each of the miners had lost what appeared to be about 20 pounds (Healy, 2010, August 23). Some had written goodbye letters to their wives and children. “Take care and protect your mother, your sister, you are now the man of the house,” Mario Sepúlveda wrote his teenage son (Franklin, 2011, p. 111). Then at 5:50 a.m. the next morning, a miracle came crashing through the roof of their dank dungeon: the tip of a drill bit. The rescue team had finally found them (Franklin, 2011).

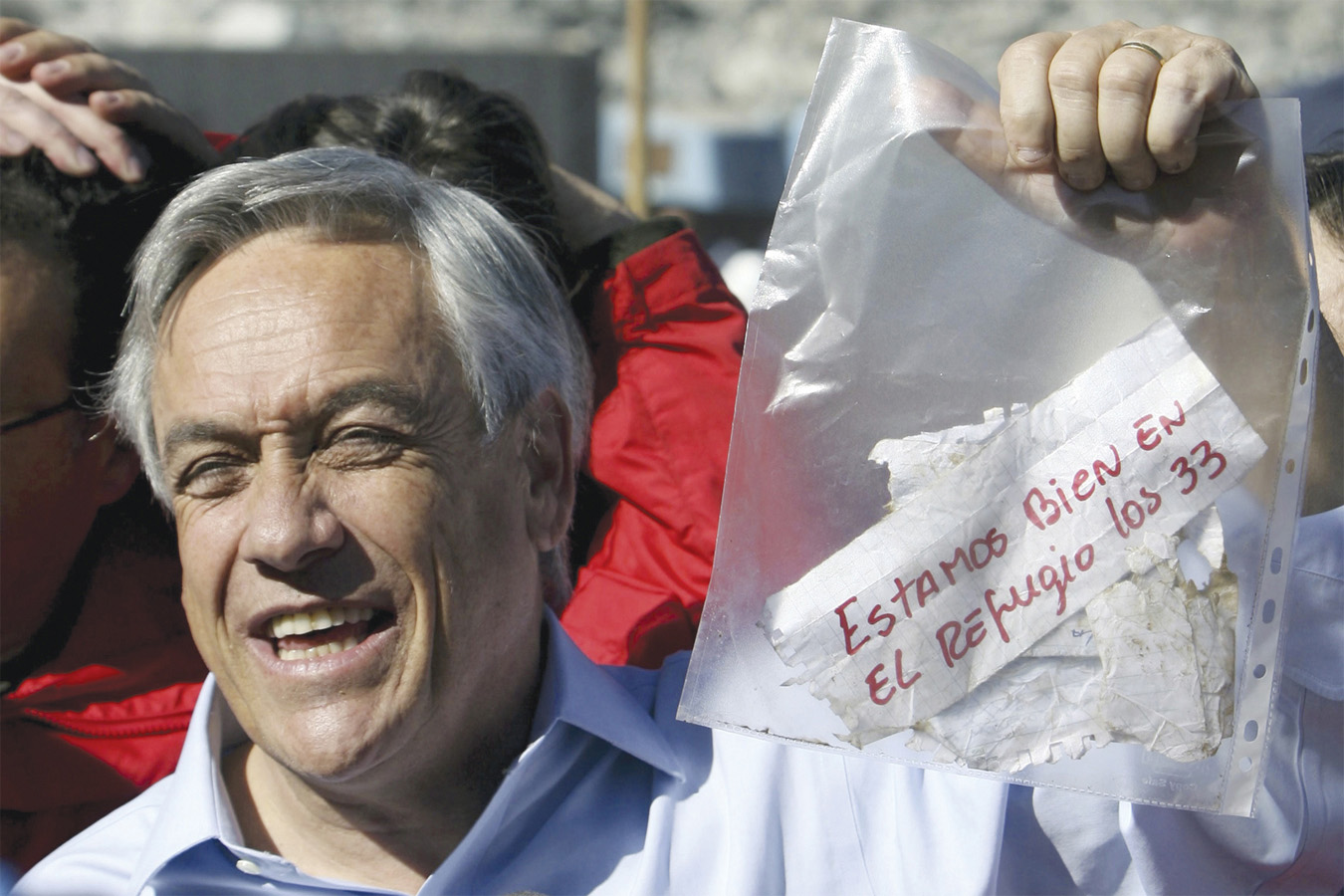

Above ground, rescuers waited anxiously as the drill slowly emerged from underground. The tip of the bit emerged with orange paint on the bottom and bags of letters—sure signs that at least one man had survived. But the real celebrations began with the discovery of a note scrawled in red marker: “Estamos bien en el refugio los 33” or “We are okay in the shelter, the 33 of us.” It was a miracle: All 33 men were alive (Franklin, 2011, p. 124).

Now that the miners had a lifeline, a tiny borehole through which food, medicine, and other essentials could be delivered, attention in the media began to shift to their psychological status. Drilling a rescue tunnel wide enough to hoist them out of the mine could take up to 4 months: Were the miners emotionally prepared to wait that long?

show what you know

Question 1.1

1. Wilhelm Wundt’s research efforts all involved __________, which is the examination of one’s own conscious activities.

- functionalism

- structuralism

- reaction time

- introspection

d. introspection

Question 1.2

2. Your psychology instructor is adamant that psychologists should only study observable behaviors. She acknowledges consciousness exists, for example, but insists it cannot be observed or documented, so should not be a topic for psychological research. Which of the following perspectives is she using?

- psychoanalytic

- behavioral

- humanistic

- cognitive

b. behavioral

Question 1.3

3. The process through which inherited traits in a given population either increase in frequency because they are adaptive or decrease in frequency because they are maladaptive is called:

- natural selection.

- functionalism.

- structuralism.

- psychology.

a. natural selection

Question 1.4

4. We have presented eight perspectives in this section. Describe how two of them are similar to each other. Pick two other perspectives and explain how they differ.

Answers will vary. Sociocultural and biopsychosocial perspectives are similar in that both examine how interactions with other people influence behaviors and mental processes. Cognitive and biological perspectives differ in that the cognitive perspective focuses on the thought processes underlying behavior, while the biological perspective emphasizes physiological processes.