Altered States of Consciousness

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we described neurotransmitters and the role they play in the nervous system. Acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter that relays messages from motor neurons to muscles, which enables movement. Too little acetylcholine causes paralysis. Here, we see how drugs can block the normal activity of acetylcholine, causing the paralysis useful during surgery.

We have so far explored a range of levels of consciousness, from wide-awake to sound asleep. But we have not addressed states of consciousness that result from the influence of agents such as drugs and alcohol, or hypnosis. Let’s take a look now at these altered states.

DRUGS, DRUGS, EVERYWHERE

You awake in the middle of the night with a dull pain around your belly button. By morning, the pain is sharp and stabbing and has migrated to your lower right abdomen, so you head to the local emergency room where doctors diagnose you with appendicitis, an inflammation of the appendix often caused by infection. You need an emergency operation to remove your appendix, and a strong anesthetic is in order: a combination of drugs to paralyze the abdominal muscles, dull the pain, and wipe out your memory of the procedure. Dr. Julien, introduced at the start of the chapter, is your anesthesiologist.

You awake in the middle of the night with a dull pain around your belly button. By morning, the pain is sharp and stabbing and has migrated to your lower right abdomen, so you head to the local emergency room where doctors diagnose you with appendicitis, an inflammation of the appendix often caused by infection. You need an emergency operation to remove your appendix, and a strong anesthetic is in order: a combination of drugs to paralyze the abdominal muscles, dull the pain, and wipe out your memory of the procedure. Dr. Julien, introduced at the start of the chapter, is your anesthesiologist.

For paralysis, Dr. Julien would probably give you a drug similar to curare, an arrowhead poison used by South American natives. Curare works by blocking the activity of the neurotransmitter called acetylcholine, which stimulates muscle contractions in the body. But curare does not cross into the brain, and therefore it does not have the power to transport you to another level of consciousness (Czarnowski, Bailey, & Bal, 2007). If curare were the only drug Dr. Julien administered, you would be lying on the operating table paralyzed yet completely awake and aware of your pain—not a pleasant scenario.

Psychoactive Drugs

LO 8 Define psychoactive drugs.

To dull the perception of pain, Dr. Julien might administer Fentanyl, which belongs to a class of drugs called opioids that we will soon discuss. And to stamp out your memory of the surgery, he would lull you into a sleeplike stupor with a drug such as Propofol and then maintain that state of sleep with other drugs. One moment you are awake, sensing, perceiving, thinking, and talking. The next moment you see nothing, hear nothing, feel nothing. It’s like you are gone. Fentanyl and Propofol are considered psychoactive drugs because the chemicals in these drugs can cause changes in psychological activities such as sensation, perception, attention, judgment, memory, self-control, emotion, thinking, and behavior—all of which may be associated with our conscious experiences.

You don’t need to visit the hospital to have a psychoactive drug experience. Mind-altering drugs are everywhere—in the coffee shop around the corner, at the liquor store down the street, and probably in your own kitchen. About 90% of people in the United States regularly use caffeine, a psychoactive drug found in coffee, soda, tea, and medicines (Alpert, 2012; Gurpegui, Aguilar, Martínez-Ortega, Diaz, & de Leon, 2004). Trailing close behind caffeine are alcohol (found in beer, wine, and liquor) and nicotine (in cigarettes and other tobacco products), two substances that present serious health risks. Another huge category of psychoactive drugs is prescription medications—drugs for pain relief, depression, insomnia, and just about any ailment you can imagine. Don’t forget the illicit, or illegal, drugs like LSD and Ecstasy. About a third of Americans aged 12 and older have tried an illicit drug at least once in their lifetime, and some 11% have used drugs in the past year, according to reported estimates (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2008).

Psychoactive drugs alter consciousness in an untold number of ways. They can rev you up, slow you down, let down your inhibitions, and convince you that the universe is on the verge of collapse. We will discuss the three major categories of psychoactive drugs—stimulants, depressants, and hallucinogens—but keep in mind that some drugs fall into more than one group.

Depressants

LO 9 Identify several depressants and stimulants and know their effects.

In his 25 years as an anesthesiologist, Dr. Julien has primarily relied on a group of psychoactive drugs that depress activity in the central nervous system, or slow things down. For this reason, we call them depressants. Dr. Julien sometimes premedicates patients, administering drugs to calm them while they wait to be wheeled into the operating room. For this purpose, he might use a benzodiazepine, which would act as a tranquilizer—a type of depressant that has a calming, sleep-inducing effect. Other examples of tranquilizers are Valium (diazepam) and Xanax (alprazolam), which are used to treat anxiety disorders. A more recent addition to the tranquilizer family is Rohypnol (flunitrazepam), also known as the “date rape drug” or “roofies,” which is legally manufactured and approved as a treatment for insomnia in other countries, but banned in the United States (Drug Enforcement Administration [DEA], 2012). Sex predators have been known to slip roofies into their victims’ drinks, especially darker-colored cocktails where the blue pills dissolve unseen. Rohypnol can cause confusion, amnesia, lowered inhibitions, and sometimes loss of consciousness, preventing victims from defending themselves or remembering the details of a sexual assault.

Barbiturates

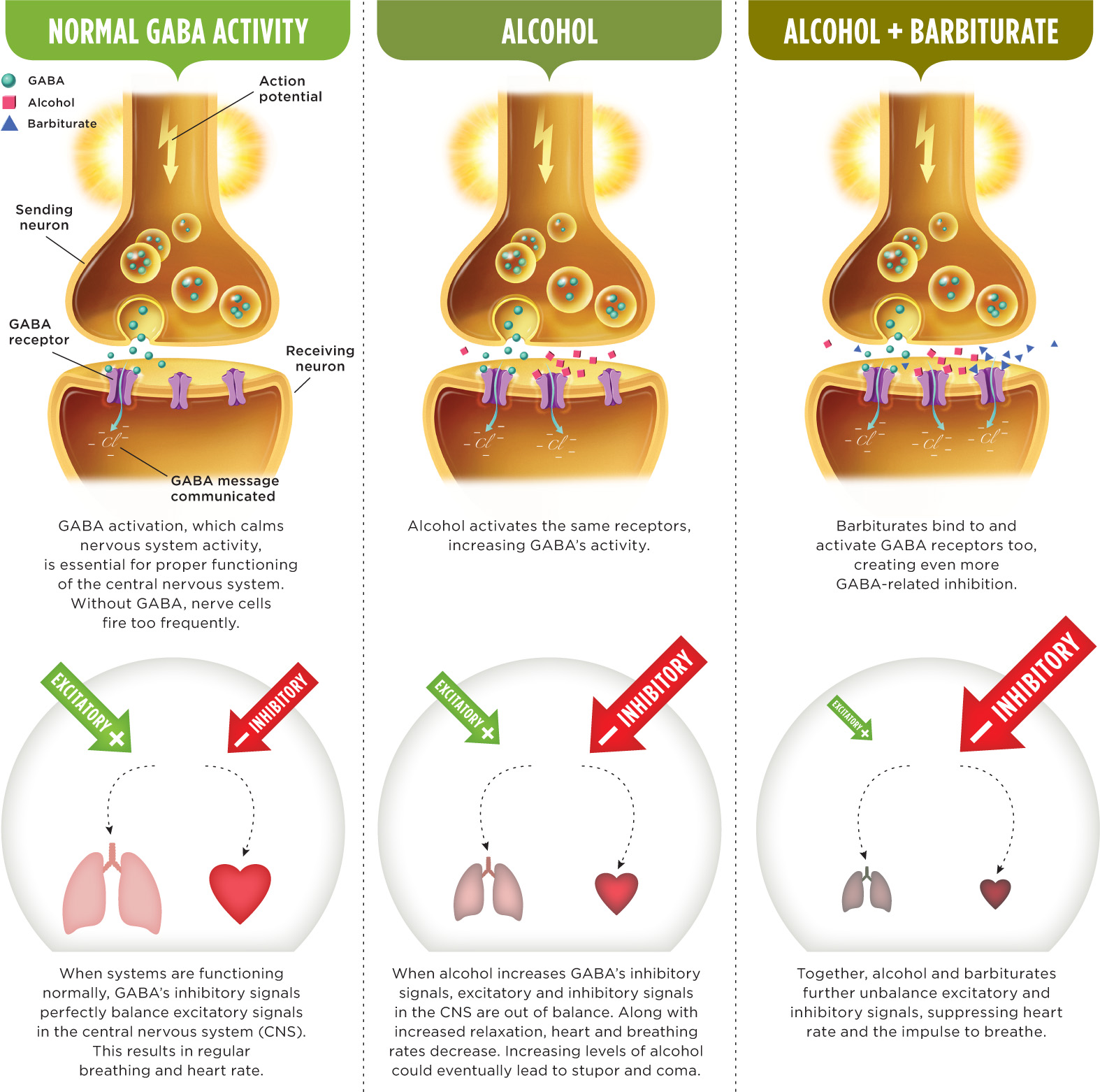

Once a patient is in the operating room and ready for surgery, Dr. Julien puts him to sleep. This process is called “induction,” and it is sometimes accomplished using another type of depressant termed a barbiturate (bär-′bi-chə-rət), which is a sedative drug that decreases neural activity. In low doses, barbiturates cause many of the same effects as alcohol—relaxation, lowering of spirits, or alternatively, aggression (Julien et al., 2011)—which may explain why they have become so popular among recreational users. But these substances are addictive and extremely dangerous when taken in excess or mixed with other drugs. If barbiturates are taken alongside alcohol, for example, the muscles of the diaphragm may relax to the point of suffocation (Infographic 4.3).

INFOGRAPHIC 4.3: The Dangers of Drugs in Combination

Taking multiple drugs simultaneously can lead to unintended and potentially fatal consequences because of how they work in the brain. Drugs can modify neurotransmission by increasing or decreasing the chemical activity. When two drugs work on the same system, their effects can be additive, greatly increasing the risk of overdose. For example, alcohol and barbiturates both bind to GABA receptors. GABA’s inhibitory action has a sedating effect, which is a good thing when you need to relax. But too much GABA will relax physiological processes to the point where unconscious, life-sustaining activities shut down, causing you to stop breathing and die.

Hundreds of deaths are caused annually in the U.S. when drugs like alcohol and barbiturates are taken in combination (Kochanek et al., 2012). In 2009 alone, 519,650 emergency room visits were attributed to use of alcohol in combination with other drugs (SAMHSA, 2010).

Opioids

Recall from the beginning of the chapter that the brain continues receiving pain impulses even when a patient is out cold on the operating table. Without proper painkilling drugs, these signals can give rise to what Dr. Julien calls “autonomic instability,” a disruption of heart rate, blood pressure, and other activities regulated by the autonomic nervous system. One way to maintain autonomic stability is to give the patient an opioid, a drug that minimizes the brain’s perception of pain. “Opioid” is an umbrella term for a large group of similarly acting drugs, some found in nature and others concocted in laboratories (synthesized replacements such as methadone). Opioids block pain, induce drowsiness and euphoria, and slow down breathing (Julien et al., 2011). There are two types of naturally occurring opioids: the endorphins produced by your body, and the opiates found in the opium poppy. The poppy-derived opioid morphine alleviates patients’ pain. Morphine is also the raw material used in making the street drug heroin, which enters the brain more quickly and has 3 times the strength (Julien et al., 2011).

Prescription Drug Abuse

Few people in the United States actually use heroin (less than 1%), and some studies suggest that number is decreasing. But another class of opioids appears to be taking its place—synthetic painkillers such as Vicodin (hydrocodone) and OxyContin (oxycodone; Fischer & Rehm, 2007; SAMHSA, 2010). Unlike heroin, these medications are legally manufactured by drug companies and legitimately prescribed by physicians. Intentionally using a medication without a doctor’s approval can lead to prescription drug abuse, and this behavior is shockingly common among teenagers, who are more vulnerable to becoming hooked or addicted (Zhang et al., 2009). Prescription drug abuse can also occur when a medication is used in a way that is not prescribed by a doctor (for example, taking too much of a medication). Nearly 1 in 10 high school seniors in the United States has abused Vicodin, and 1 in 20 has abused OxyContin. Over half report getting such prescription meds from friends and relatives (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2011). Opioid abuse is an epidemic among high school students, and many don’t understand how easy it is to become hooked on these drugs. Sadly, drug overdose deaths recently surpassed the number of deaths resulting from car accidents in the United States (Moisse, 2011, September 20).

Alcohol

We end our coverage of depressants with alcohol, which, like other drugs in its class, has played a central role in the history of anesthesia. The ancient Greek doctor Dioscorides gave his surgical patients a special concoction of wine and mandrake plant (Keys, 1945), and 19th-century Europeans used an alcohol-opium mixture called laudanum for anesthetic purposes (Barash, Cullen, Stoelting, & Cahalan, 2009). These days, you won’t find anesthesiologists knocking out patients with alcohol, but you will encounter plenty of people intoxicating themselves.

Binge Drinking

Alcohol is the most commonly used depressant in the United States. Around 15% of adults and 25% of teenagers report that they binge drink (consuming four or more drinks for women and five or more for men, on one occasion or within a short time span) at least once a month (Naimi et al., 2003; Wen et al., 2012). Many people think binge drinking is fun, but they might change their minds if they read the research. Studies have linked binge drinking to poor grades, aggressive behavior, sexual promiscuity, and accidental death. In 2005 almost 2,000 college students in the United States died in alcohol-related accidents (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). Think getting wasted is sexy? Consider this: Alcohol impairs sexual performance, particularly for men, who may have trouble obtaining and sustaining an erection.

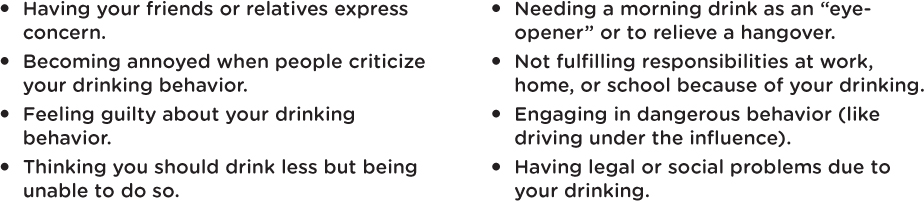

You don’t have to binge drink in order to have an alcohol problem (Figure 4.1). Some people cannot get through the day without a midday drink; others need alcohol to unwind or fall asleep. The point is there are many forms of alcohol misuse. About 8.5% of the adult population in the United States (nearly 1 in 10 people) struggles with alcohol dependence or some other type of drinking problem (Grant et al., 2004). Drinking can destroy families, careers, and human life.

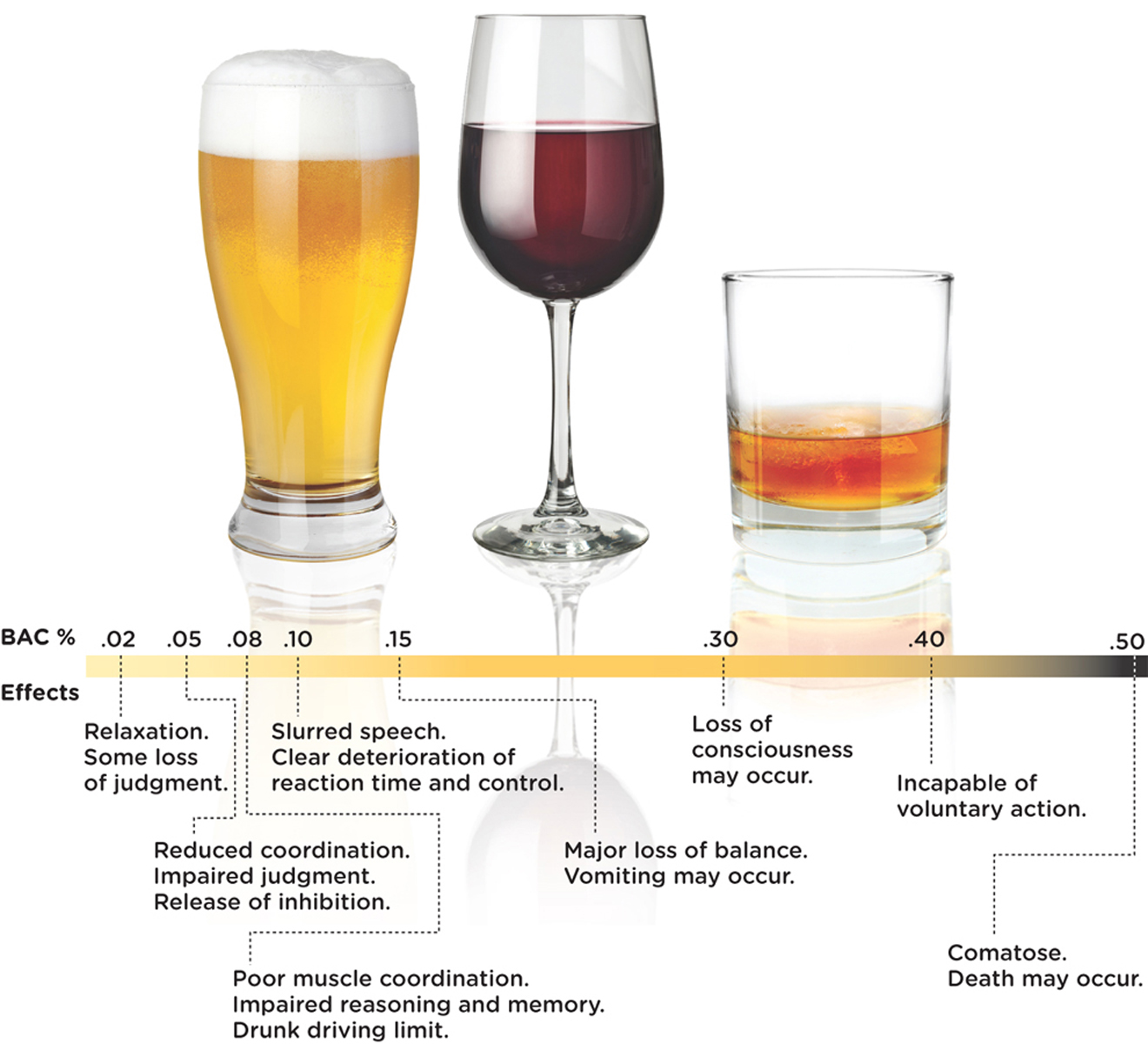

Alcohol and The Body

Let’s stop for a minute and examine how alcohol influences consciousness (Figure 4.1). People sometimes say they feel “high” when they drink. How can such a statement be true when alcohol is a depressant, a drug that slows down activity in the central nervous system? Alcohol boosts the activity of GABA, a neurotransmitter that dampens activity in certain neural networks, including those that regulate social inhibition—a type of self-restraint that keeps you from doing things you will regret the next morning. It is this release of social inhibition that can lead to feelings of euphoria. Drinking affects other conscious processes, such as reaction time, balance, attention span, memory, speech, and involuntary life-sustaining activities like breathing (Howland et al., 2010; McKinney & Coyle, 2006). Drink enough, and these vital functions will shut down entirely, leading to coma and even death.

The female body is less efficient at breaking down (metabolizing) alcohol. Even when we control for body size and the muscle-to-fat ratio, we see that women achieve higher blood alcohol levels (and thus a significantly stronger “buzz”) than men who have consumed equal amounts. Why? Because men have more of an alcohol-metabolizing enzyme in their stomachs, which means they start to break down alcohol almost immediately after ingestion. In a woman, most of the alcohol clears the stomach and enters the bloodstream and brain before the liver finally breaks it down (Toufexis, 2001).

The Consequences of Drinking

Light alcohol consumption by adults—one to two drinks of wine, beer, or liquor a day—may have some cardiovascular and cognitive benefits (Cervilla, Prince, Joels, Lovestone, & Mann, 2000; Mukamal, Maclure, Muller, Sherwood, & Mittleman, 2001). Excessive drinking, on the other hand, is associated with a host of health problems. Overuse of alcohol can lead to malnourishment, cirrhosis of the liver, and Wernicke–Korsakoff Syndrome, which can include symptoms such as confusion and memory problems. It has also been linked to heart disease, various types of cancer, tens of thousands of traffic deaths every year, and fetal-alcohol syndrome in children with mothers who drank during pregnancy. Deaths due to overuse of alcohol, numbering about 75,000 annually, are the third most common type of preventable death in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2004; Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, & Gerberding, 2004). Read through Figure 4.2 for some warning signs of problematic drinking.

Stimulants and Hallucinogens

Not all drugs used in anesthesia are depressants. Did you know that some doctors use cocaine as a local anesthetic for nose and throat surgeries (Simmer, 2012)? Cocaine is a stimulant—a drug that increases neural activity in the central nervous system, producing effects such as heightened alertness, energy, and an elevated mood (Julien et al., 2011). When applied topically, cocaine blocks sensation in the peripheral nerves and thereby numbs the area.

Cocaine

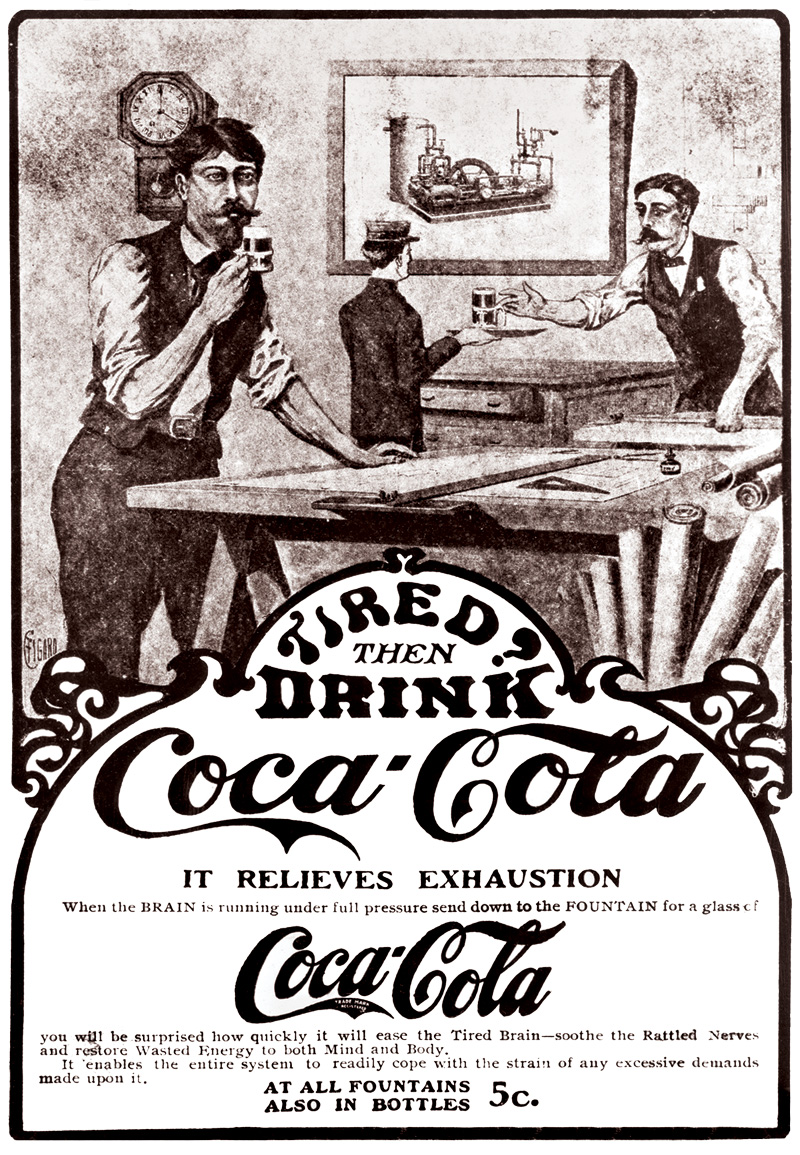

The first to tap into cocaine’s pain-zapping potential were the ancient Peruvians, who chewed the leaves of the coca plant (which contain about 1% cocaine) and then applied their saliva to surgical incisions. The coca plant, they believed, was a divine gift; chewing the leaves quenched their hunger, lifted their sadness, and restored their energy. Thousands of years later, in 1860, a German chemist named Albert Niemann extracted the active ingredient in the coca leaf and dubbed it “cocaine” (Julien et al., 2011; Keys, 1945). Within a few decades doctors were using cocaine for anesthesia, Sigmund Freud was giving it to patients (and himself), and Coca-Cola was putting it in soda (Keys, 1945; Musto, 1991).

While cocaine is illegal in the United States and most other countries, it is among the most widely used illicit drugs. Depending on the form in which it is prepared (powder, rocks, and so on), it can be snorted, injected, or smoked. The sense of energy, euphoria, and other alterations of consciousness that cocaine induces after entering the bloodstream and infiltrating the brain last anywhere from 5 to 30 minutes (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2010a). Cocaine produces a rush of pleasure and excitement by amplifying the effects of dopamine and norepinephrine. But the coke high comes at a steep price. Any time you take cocaine, you put yourself at risk for suffering a stroke or heart attack, even if you are young and healthy. Cocaine is implicated in more emergency room visits than any other illegal drug (Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2009). It is also extremely addictive. Many users find they can never quite duplicate the high they experienced the first time, so they take increasingly higher doses, developing a physical need for the drug, increasing their risk of effects such as anxiety, insomnia, and schizophrenia-like psychosis when they stop using it (Julien et al., 2011).

Cocaine use grew rampant in the 1980s. That was the decade crack—an ultra-potent (and ultra-cheap) crystalline form of cocaine—began poisoning America’s inner cities. Although cocaine is still a major problem, another stimulant has come to rival it in popularity—one that is ridiculously cheap, easy to make, and capable of producing a 24-hour high or euphoric rush—methamphetamine.

Amphetamines

Methamphetamine belongs to a family of stimulants called the amphetamines (am-’fe-tə-′mēnz). Doctors used amphetamines to treat medical conditions as diverse as head injury and excessive hiccups in the 1930s and 1940s (Julien et al., 2011). Methamphetamine was once used by soldiers and factory workers during World War II for energy and to enhance performance (Lineberry & Bostwick, 2006). Nonprescription use of methamphetamine is illegal, but people have learned how to brew it in their own laboratories, using ingredients from ordinary household products such as over-the-counter cough medicines, drain cleaner, and battery acid. “Cooking meth” is a dangerous enterprise. The flammable ingredients, combined with the reckless mentality of “tweaking” cookers, make for toxic fumes and thousands of accidental explosions every year (Lineberry & Bostwick, 2006). Despite the enormous risk, many people continue to cook meth at home, endangering and sometimes killing their own children.

Methamphetamine stimulates the release of the brain’s pleasure-producing neurotransmitter dopamine, causing a surge in energy and alertness similar to a cocaine high. It also tends to increase one’s sex drive and suppress appetite. But unlike cocaine, which the body eliminates quickly, meth lingers in the body (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2006). Brain imaging studies show that chronic meth use causes serious brain damage in the frontal lobes and other areas, still visible even among those who have been clean for 11 months. This may explain why so many meth users suffer from lasting memory and movement problems (Krasnova & Cadet, 2009; Volkow et al., 2001). Other severe consequences of meth use include extreme weight loss; tooth decay (“meth mouth”); psychosis with hallucinations that can come and go for months, if not years, after quitting; and sudden death (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2006).

Caffeine

Most people have not experimented with illegal stimulants like cocaine and meth, but many have used caffeine. We usually associate caffeine with beverages like coffee, but this pick-me-up drug also lurks in places you wouldn’t expect, such as in over-the-counter cough medicines, chocolate, and face creams. Caffeine works by blocking the action of adenosine, a neurotransmitter that normally muffles the activity of excitatory neurons in the brain (Julien et al., 2011). By interfering with adenosine’s calming effect, caffeine makes you feel physically and mentally wired. A cup of coffee might help you stay up later, exercise longer and harder, and get through more pages in your textbooks. Moderate caffeine use (up to four cups of coffee per day) has been associated with increased alertness, enhanced recall ability, elevated mood, and greater endurance during physical exercise (Ruxton, 2008). Some studies have also linked moderate long-term consumption with lower rates of depression and suicide, and even reduced cognitive decline with aging (Lara, 2010; Rosso, Mossey & Lippa, 2008).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed the problem with possible third factors and correlations. Here, we need to be cautious about making too strong a statement about coffee causing positive health outcomes, because third factors could be involved in increased caffeine consumption and better health.

With all these promising data about caffeine, you may feel like running to your local coffee shop to order a triple-shot latte. But just because researchers find a link, for example, between caffeine and positive health outcomes, we should not necessarily conclude that caffeine is responsible for it. Maybe people who have a low risk for depression and dementia also enjoy drinking coffee. Or perhaps coffee drinkers are more likely to engage in regular exercise, an activity linked to improved mood and cognition. Remember, correlation does not prove causation. What’s more, too much caffeine can make your heart race, your hands tremble, and your mood turn sour and irritable. It takes several hours for your body to metabolize caffeine, so a late afternoon mocha latte may still be present in your system as you lie in bed at midnight counting sheep—with no luck.

Tobacco

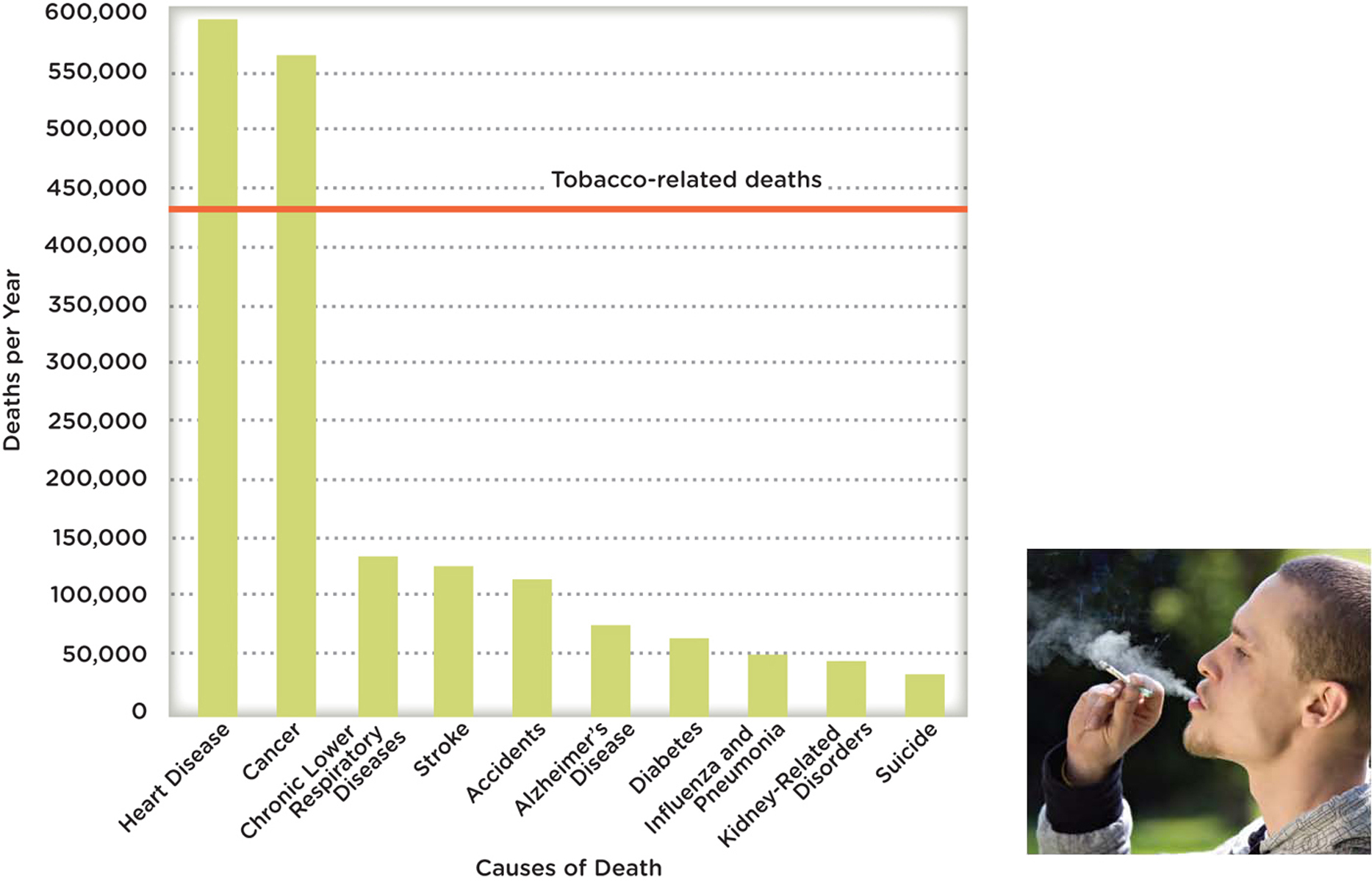

What do you think is the number one cause of premature death worldwide—AIDS, illegal drugs, road accidents, murder, suicide? None of the above (Figure 4.3). Tobacco causes more deaths than any of these other factors combined (BBC News, 2010; World Health Organization [WHO], 2008b). The use of cigarettes and other tobacco products claims 5 million lives every year, and half a million in the United States alone (Kasisomayajula et al., 2010). Smoking can lead to lung cancer, emphysema, heart disease, and stroke (CDC, 2008b). The average smoker loses approximately 10 to 15 years of her life.

Despite these harrowing statistics, about 1 in 5 adults in the United States continues to light up (CDC, 2010). They say it makes them feel relaxed yet more alert, less hungry, and more tolerant of pain. And those who try to kick the habit find it exceedingly difficult to do so. Cigarettes and other tobacco products contain a highly addictive stimulant called nicotine, which sparks the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine. Nicotine use appears to be associated with activity in the same brain area that is activated with cocaine, another drug that is also extremely difficult to give up (Pich et al., 1997; Zhang, Dong, Doyon, & Dani, 2012). The few who do succeed face a steep uphill battle. Around 90% of quitters relapse within 6 months (Non-nemaker et al., 2011), suggesting that relapse is a normal experience when quitting, not a sign of failure.

Smoking is not just a problem for the smoker. It is a problem for spouses, children, friends, and anyone who is exposed to the secondhand smoke. Secondhand smoke is particularly dangerous for children, whose developing tissues are especially vulnerable (Chapter 8). By smoking, parents increase their children’s risk for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), respiratory infections, asthma, and lung cancer (CDC, 2012e). Secondhand smoke contributes to 21,400 lung cancer deaths and 379,000 heart disease deaths worldwide (Öberg, Jaakkola, Woodward, Peruga, & Prüss-Ustün, 2011), and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012e), “There is no risk-free level of exposure”. In recent years, researchers have also become concerned about the health implications of thirdhand smoke, the combination of cigarette toxins (including lead, which is a known neurotoxin) that linger in rooms, elevators, and other small spaces long after a smoker has left the scene. Thirdhand smoke is what you smell when you walk into a hotel room and think, Hmm, someone’s been smoking in here (Winickoff et al., 2009).

LO 10 Discuss some of the hallucinogens.

We have learned how various depressants and stimulants are used in anesthesia. Believe it or not, there is also a place for hallucinogens (hə-’lü-sə-nə-jənz)—drugs that produce hallucinations (sights, sounds, odors, or other sensations of things that aren’t actually present), altered moods, and distorted perception and thought. Phencyclidine (PCP or angel dust) and ketamine (Special K) are sometimes referred to as psychedelic anesthetics because they were developed to block pain and memory in surgical patients during the 1950s and 1960s (Julien et al., 2011). PCP is highly addictive and extremely dangerous. Because users cannot feel normal pain signals, they run the risk of unintentionally harming or killing themselves. Long-term use can lead to depression and memory impairment. The milder of the two, ketamine, continues to be used in hospitals, but PCP was abandoned long ago. Its effect was just too erratic.

LSD

The most well-known hallucinogen is probably lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD; lə-’sər-jik; dī-′e-thə-’la-′mīd)—the odorless, tasteless, and colorless substance that produces extreme changes in sensation and perception. People using LSD may report seeing “far out” colors and visions of spirals and other geometric forms. Some people experience a crossover of sensations, “tasting sound” or “hearing colors.” Emotions run wild and bleed into one another; the person “tripping” can quickly flip between depression and joy, excitement and terror (Julien et al., 2011). Trapped on this sensory and emotional roller coaster, some people panic and injure themselves. Others believe that LSD opens their minds, offers new insights, and expands their consciousness. The outcome of a “trip” depends a great deal on the environment and people who are there. LSD is not often overused, and its reported use has remained at an all-time low (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012). Long-term use may be associated with depression and other psychological problems, including flashbacks that can occur weeks, months, or years after taking the drug. Fatigue, stress, and illness may trigger flashbacks (Thurlow & Girvin, 1971).

MDMA

In addition to the traditional hallucinogens, there are quite a few “club drugs,” or synthetic “designer drugs,” used at parties, raves, and dance venues. The most popular among them is methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA; meth′ĭ-lēn-dī-ok′sē-meth′am-fet′ă-mēn), commonly known as Ecstasy. Ecstasy is chemically similar to the stimulant methamphetamine and the hallucinogen mescaline, and thus produces a combination of stimulant and hallucinogenic effects (Barnes et al., 2009; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2010b).

An Ecstasy trip might bring on feelings of euphoria, love, openness, heightened energy, and floating sensations, as well as intense anxiety and depersonalization, with the user feeling like a detached spectator, watching himself from the outside without having any control. Ecstasy can also cause a host of changes to the body, including decreased appetite, lockjaw, blurred vision, dizziness, rapid heart rate, and dehydration (Gordon, 2001, July 5; Noller, 2009). Dancing in hot, crowded conditions while on Ecstasy can lead to severe heat stroke, seizures, even cardiac arrest and death (Parrott, 2004). Every year, thousands of Ecstasy users leave raves and all-night parties in ambulances. Between 2004 and 2009, the number of emergency room visits associated with the drug climbed by 123% (Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2009). Despite its dangers, Ecstasy is still a popular illicit drug (SAMHSA, 2012).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we reported that serotonin is critical for the regulation of mood, appetite, aggression, and automatic behaviors like sleep. Here, we see how the use of Ecstasy can alter levels of this neurotransmitter.

Ecstasy triggers a sudden general unloading of serotonin in the brain, after which serotonin activity is depleted until the neurotransmitters’ levels are restored (Klugman & Gruzelier, 2003). Studies of animals have shown that even short-term exposure to MDMA can cause long-term, perhaps even permanent, damage to the brain’s serotonin pathways, and there is mounting evidence that a similar type of damage in reuptake from the synapse and storage of serotonin occurs in humans as well (Campbell & Rosner, 2008; Reneman et al., 2001; Ricaurte & McCann, 2001). One study found evidence that women’s brains are more susceptible to Ecstasy damage than men’s, but larger studies are needed to confirm this finding (Reneman et al., 2001). The growing consensus is that even light-to-moderate Ecstasy use can handicap the brain’s memory system, and heavy use may impair higher-level cortical functions, such as planning for the future and shifting attention (Klugman & Gruzelier, 2003). Studies also suggest that Ecstasy users are more likely to experience symptoms of depression (Guillot, 2007).

Marijuana

We end our discussion with the most widely used illegal (in most states) drug, and one of the most popular in all the Western world: marijuana (Compton, Grant, Colliver, Glantz, & Stinson, 2004; SAMHSA, 2008). Forty-two percent of American teenagers have already tried marijuana by the time they graduate from high school (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2010c). Attitudes tend to be more casual about marijuana than other illegal drugs. “It’s no big deal,” a user might say, “you can’t get addicted.” But these kinds of assumptions are misleading. Recent studies suggest that marijuana use can lead to dependence, memory impairment, and deficits in attention and learning (Harvey, Sellman, Porter, & Frampton, 2007; Kleber & DuPont, 2012). Others identify it as a cause of some chronic psychological disorders (Reece, 2009). The long-term use of marijuana has also been associated with reduced motivation (Reece 2009), and linked to respiratory problems, impaired lung functioning, and suppression of the immune system (Iversen, 2003; Pletcher et al., 2012). In addition, the smoke from marijuana contains 50 to 70% more cancer-causing hydrocarbons than tobacco (Kothadia et al., 2012). Smoking marijuana also causes a temporary dip in sperm production and a greater proportion of abnormal sperm (Brown & Dobs, 2002).

Marijuana comes from the hemp plant Cannabis sativa, which has long been used as—surprise—an anesthetic. The 3rd-century Chinese physician Hua T’o reportedly used hemp to put his patients to sleep before performing surgery (Keys, 1945). These days, doctors prescribe marijuana to stimulate patients’ appetites and suppress nausea, but its medicinal use is not without debate. Studies suggest that marijuana does effectively reduce the nausea and vomiting linked to chemotherapy (Grotenhermen & Müller-Vahl, 2012; Iversen, 2003), but there is conflicting evidence about its long-term effects on the brain (Schreiner & Dunn, 2012).

Marijuana’s active ingredient is tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; te-trə-hī-drə-kə-′na-bə-′n⊙l), which toys with consciousness in a variety of ways, making it hard to classify the drug into a single category (for example, stimulant, depressant, or hallucinogen). In addition to altering pain perception, THC can induce mild euphoria, and create intense sensory experiences and distortions of time. At higher doses, THC may cause hallucinations and delusions (Murray, Morrison, Henquet, & Di Forti, 2007).

Some of marijuana’s effects linger long after the initial high is over. Impairments in learning and memory may persist for days in adults (weeks for adolescents), and long-term use may lead to addiction (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2010c; Schweinsburg, Brown, & Tapert, 2008).

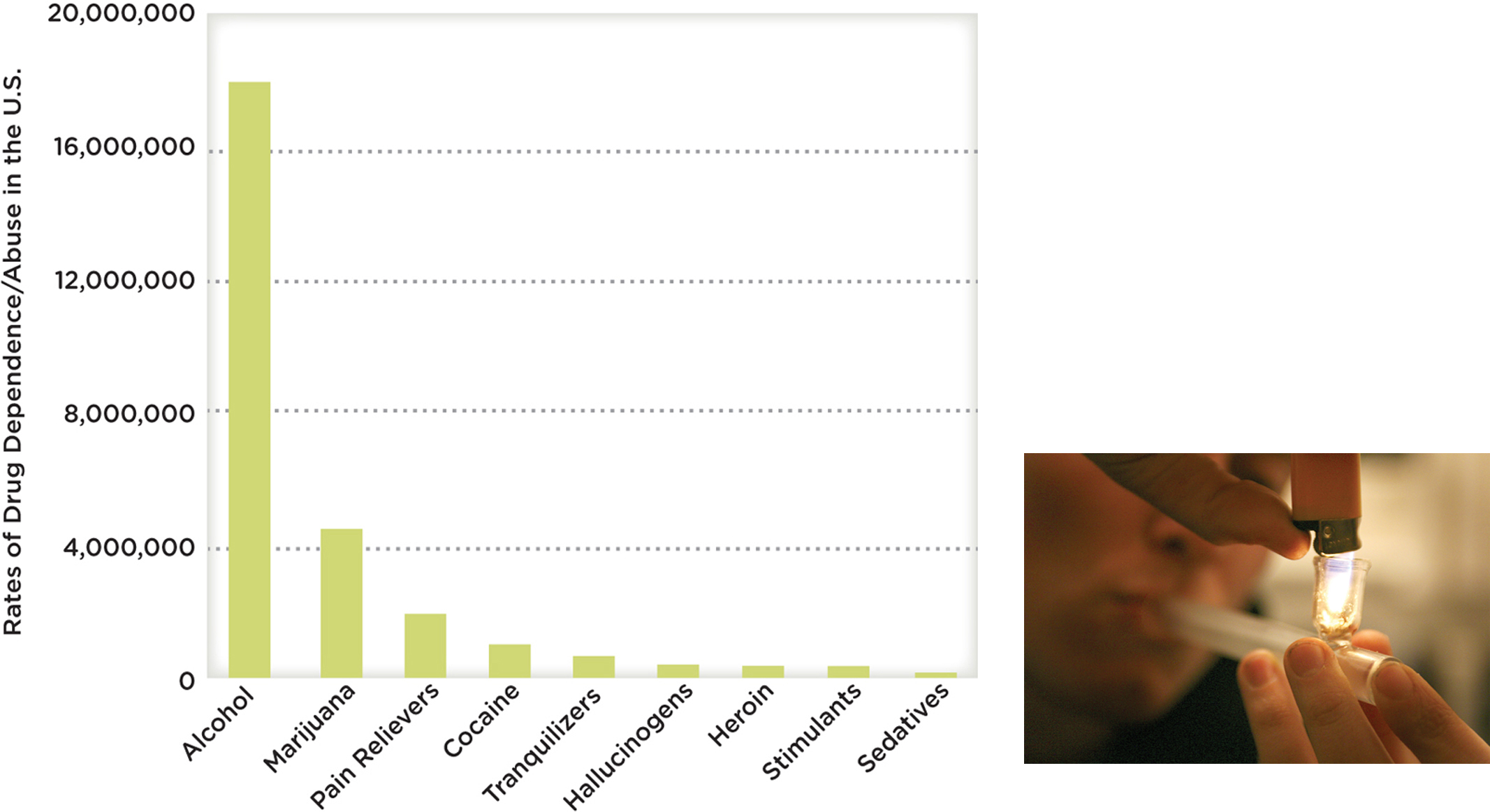

Overuse and Addiction

We often joke about being “addicted” to our coffee or soda, but do we understand what this really means? Historically, the term addiction has been used (both by lay-people and professionals) to refer to the urges people experience for using a drug or engaging in an activity to such an extent that it interferes with their functioning or may even be dangerous (see Figure 4.4 on drug dependence in the United States). This could mean a gambling habit that depletes your bank account, a sexual appetite that destroys your marriage, or perhaps even a social media fixation that prevents you from holding down a job. It is important to note the term addiction has been omitted from the American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual due to its “uncertain definition and potentially negative connotation” (APA, 2013, pg 485).

SOCIAL MEDIA and psychology

Is it difficult for you to sit through a movie without checking your Twitter “Mentions”? Are you constantly looking at your Facebook News feed in between work e-mails? Do you sleep with your iPhone? If you answered “yes” to any of the above, you are not alone. People around the world, from Indonesia to the United Kingdom, are getting hooked on social media—so hooked in some cases that they are receiving treatment for social media addiction (Maulia, 2013, February 15; NBC Universal, 2013, February 12).

Is it difficult for you to sit through a movie without checking your Twitter “Mentions”? Are you constantly looking at your Facebook News feed in between work e-mails? Do you sleep with your iPhone? If you answered “yes” to any of the above, you are not alone. People around the world, from Indonesia to the United Kingdom, are getting hooked on social media—so hooked in some cases that they are receiving treatment for social media addiction (Maulia, 2013, February 15; NBC Universal, 2013, February 12).

“…THE URGE TO USE MEDIA WAS HARDER TO RESIST THAN SEX, SPENDING MONEY, ALCOHOL….”

Facebook and Twitter may be habit forming, but you would think these sites would be easier to resist than, say, coffee or cigarettes. Such is not the case, according to one recent study. With the help of smartphones, researchers kept tabs on the daily desires of 205 young adults and found the urge to use media was harder to resist than sex, spending money, alcohol, coffee, or cigarettes (Hofmann, Vohs, & Baumeister, 2012). These findings are thought provoking, and this line of research is one to follow, but don’t allow one study to minimize the serious and long-standing issue of drug addiction. The American Psychiatric Association (2013) does not consider behavioral addictions to be mental disorders. Further, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (2009) defines addiction to drugs, in particular, as “a chronic, relapsing disease characterized by compulsive drug seeking and abuse and by long-lasting neurochemical and molecular changes in the brain”. You read it right: Substance use changes your brain.

Physiological and Psychological Dependence

LO 11 Explain how physiological and psychological dependence differ.

Substance use can be fueled by both physiological and psychological dependence. Physiological dependence means the body no longer functions normally without the drug. Want to know if you are physiologically dependent on your morning cup of Joe? Try removing it from your routine for a few days and see if you get a headache or feel fatigued. If your answers are yes and yes, odds are that you have experienced withdrawal, a sign of physiological dependence. withdrawal is the constellation of symptoms that surface when a drug is removed or withheld from the body, and it’s not always as mild as a headache and fatigue. An alcoholic who suddenly stops drinking (or significantly cuts down) may suffer from delirium tremens (DTs), withdrawal symptoms that include sweating, restlessness, hallucinations, severe tremors, and seizures. Withdrawal symptoms disappear when you take the drug again, and because the symptoms do go away, you are more likely to continue using the drug. The removal of the unpleasant symptoms acts as negative reinforcement for taking the drug (Chapter 5). In this way, withdrawal powers the addiction cycle.

Another sign of physiological dependence is tolerance. Persistent drug and alcohol use alters the chemistry of the brain and body. Over time, your system adapts to the drug and therefore needs more and more of the substance to re-create the original effect. If it once took you two beers to unwind, but now takes four, then tolerance has probably set in. Tolerance increases the risk for accidental overdose, because more drug is needed to obtain the desired effect.

Psychological dependence occurs without the evidence of tolerance or withdrawal symptoms, but is indicated by many other problematic symptoms. Individuals with psychological dependence believe, for example, they need the drug because it will increase their emotional or mental well-being. The “pleasant” effects of a drug can act as positive reinforcement for taking the drug (Chapter 5). Let’s say a smoker has a cigarette, fulfilling her physical need for nicotine. If the phone rings, she might answer it and light up a cigarette, because she has become accustomed to smoking and talking on the phone at the same time. It is an urge or craving, not a physical need. The cues associated with using the telephone facilitated the smoker’s urge to light up (Bold, Yoon, Chapman, & McCarthy, 2013).

Psychologists and psychiatrists have developed specific criteria for drawing the line between use and overuse. Overuse is maladaptive and causes significant impairment or distress to the user and/or his family: problems at work or school, neglect of children or household duties, physically dangerous behaviors, and so forth. In addition, the behavior has to be sustained for a certain period of time (that is, over a 12-month period). The American Psychiatric Association (2013) has established these criteria to help professionals distinguish between drug use and substance use disorder.

Depressants, stimulants, hallucinogens, marijuana—every drug we have discussed, and every drug imaginable—must gain entrance to the body in order to access the brain. Some are inhaled, others snorted or injected directly into the veins, all altering the state of consciousness of the user (TABLE 4.4). But is it possible to enter an altered state of consciousness without using a substance? It is time to explore hypnosis.

| Drug | Classification | Effects | Potential Harm |

| Alcohol | Depressant | disinhibition, feeling “high” | coma, death |

| Barbiturates | Depressant | decreased neural activity, relaxation, possible aggression | loss of consciousness, coma, death |

| Caffeine | Stimulant | alertness, enhanced recall, elevated mood, endurance | heart races, trembling, insomnia |

| Cocaine | Stimulant | energy, euphoria, rush of pleasure | heart attack, stroke, anxiety, psychosis |

| Heroin | Depressant | pleasure-inducing, reduces pain, rush of euphoria and relaxation | boils on the skin, hepatitis, liver disease, spontaneous abortion |

| LSD | Hallucinogen | extreme changes in sensation and perception, emotional rollercoaster | depression, long-term flashbacks, other psychological problems |

| Marijuana | Hallucinogen | stimulates appetite, suppresses nausea, relaxation, mild euphoria, distortion of time, intense sensory experience | respiratory problems, immune system suppression, cancer, memory impairment, deficits in attention and learning |

| MDMA | Stimulant; hallucinogen | euphoria, heightened energy, anxiety, and depersonalization | blurred vision, dizziness, rapid heart rate, dehydration, heat stroke, seizures, cardiac arrest, and death |

| Methamphetamine | Stimulant | energy, alertness, increases sex drive, suppresses appetite | lasting memory and movement problems, severe weight loss, tooth decay, psychosis, sudden death |

| Opioids | Depressant | blocks pain, induces drowsiness, euphoria, slows down breathing | respiratory problems during sleep, falls, constipation, sexual problems, overdose |

| Tobacco | Stimulant | relaxed, alert, more tolerant of pain | cancer, emphysema, heart disease, stroke, reduction in life span |

| Most drugs can be classified under one of the major categories listed above, but there are substances, such as MDMA, that fall into more than one class. Psychoactive drugs carry serious risks. | |||

Hypnosis

LO 12 Describe hypnosis and explain how it works.

Ask a random group of mothers to report their most physically painful experience, and we suspect most will say “childbirth.” Some women welcome the pain of labor, viewing it as a rite of passage into motherhood. Others opt for some form of pain management, often taking drugs. Some choose meditation, a form of relaxation that has been associated with a reduction in “negative” emotions (Chapter 12). Many women choose deep-breathing. Some even call upon the use of hypnosis.

There is research suggesting that hypnosis does ease the pain associated with childbirth and surgery, reducing the need for painkillers (Cyna, McAuliffe, & Andrew, 2004; Wobst, 2007). With the help of PET scans, some researchers have found evidence that hypnosis induces changes in the brain that might explain this diminished pain perception (Faymonville et al., 2000; Rainville, Duncan, Price, Carrier, & Bushnell, 1997). Dr. Julien agrees that hypnosis, meditation, and other relaxation techniques may indeed reduce anxiety and pain, but only to a certain extent. So if you plan to go under the knife with hypnosis as your sole form of pain management, don’t be surprised if you feel the piercing sensation of the scalpel.

The term hypnosis was taken from the Greek root word for “sleep,” but it is by no means the equivalent of sleep. Most would agree hypnosis is an altered state of consciousness that allows for changes in perceptions and behaviors, which result from suggestions made by the hypnotist. “Changes in perceptions and behaviors” can mean a lot of things, of course, and there is some debate about what hypnosis is. Before going any further, let’s be clear about what hypnosis isn’t.

CONTROVERSIES

False Claims About Hypnosis

NO ONE CAN FORCE YOU TO BECOME HYPNOTIZED

Popular conceptions of hypnosis often clash with scientists’ understanding of the phenomenon. Let’s take a look at some examples:

Popular conceptions of hypnosis often clash with scientists’ understanding of the phenomenon. Let’s take a look at some examples:

- People can be hypnotized without consent: You cannot force someone to be hypnotized; they must be willing.

- Hypnotized people will act against their own will: Stage hypnotists seem to make people walk like chickens or miscount their fingers, but these are things they would likely be willing to do when not hypnotized.

- Hypnotized people can exhibit “superhuman” strength: Hypnotized or not, people have the same capabilities (Druckman & Bjork, 1994). Stage hypnotists often choose feats that their hypnotized performers could achieve under normal circumstances.

- Hypnosis helps people retrieve lost memories: Studies find that hypnosis may actually promote the formation of false memories and one’s confidence in those memories (Kihlstrom, 1985).

- Hypnotized people experience age regression. In other words, they act childlike: Hypnotized people may indeed act immaturely, but the underlying cognitive activity is that of an adult (Nash, 2001).

- Hypnosis induces long-term amnesia: Hypnosis cannot make you forget your first day of kindergarten or your wedding. Short-term amnesia is possible if the hypnotist specifically suggests that something will be forgotten after the hypnosis wears off.

Now that some misconceptions about hypnosis have been cleared up, let’s focus on what we know. Researchers propose the following characteristics are evident in a hypnotized person: (1) ability to focus intently, ignoring all extraneous stimuli; (2) heightened imagination; (3) an unresisting and receptive attitude; (4) decreased pain awareness; (5) high responsivity to suggestions (Kosslyn, Thompson, Costantini-Ferrando, Alpert, & Spiegel, 2000; Silva & Kirsch, 1992).

Does this process have any application to real life? With some limited success, hypnosis has been used therapeutically to treat phobias and commercially to help people change lifestyle habits (Green, 1999; Kraft, 2012). Hypnosis can also be used to reduce headaches and other pains associated with stress (Patterson & Jensen, 2003). Athletes use self-hypnosis to improve performance.

Imagine you are using hypnosis for one of these purposes, headaches, for example. How would a session with a hypnotist proceed? Probably something like this: The hypnotist talks to you in a calm, quiet voice, running through a list of suggestions on how to relax. She might suggest that you sit back in your chair and choose a place to focus your eyes. Then she quietly suggests that your eyelids are starting to droop, and you feel like you need to yawn. You grow tired and more relaxed. Your breathing slows. Your arms feel so heavy that you can barely lift them off the chair. Or the hypnotist might suggest that you are going down steps, and ask you to focus attention on her voice. Hypnotists who are very good at this procedure can do an induction in less than a minute, especially if they know the individual being hypnotized.

Once you are in this altered state of consciousness, you may be open to suggestion. If, say, the hypnotist suggested you could not lift your feet off the ground, then you might actually feel this way. Or if she suggested that you will not remember your own middle name after coming out of hypnosis, this posthypnotic suggestion may very well play out.

People in hypnotic states sometimes report having sensory experiences that deviate from reality; they may, for example, see or hear things that are not there. In a classic experiment, participants were hypnotized to believe they wouldn’t experience pain when asked to place one hand in a container filled with ice-cold water. With their other hand, they were asked to press a button if they experienced pain. Amazingly, the participants reported feeling no pain. However, they actually did press the button indicating pain during their hypnotic session (Hilgard, Morgan, & Macdonald, 1975). This suggests a “divided consciousness,” that is, part of our consciousness is always aware, even when hypnotized and instructed to feel no pain. People under hypnotic states can also experience temporary blindness and deafness.

Theories of Hypnosis

There are many theories to explain hypnosis. According to Hilgard (1977, 1994), hypnotized people experience a “split” in awareness, or consciousness. There is an ever-present hidden observer that oversees the events of our daily lives. You are listening to a boring lecture, picking up a little content here and there, but also thinking about that juicy gossip you heard before class. Your mind is working on different levels, and the hidden observer is keeping track of everything. In a hypnotic state, the hidden observer is still aware of what is transpiring in the environment, while another stream of mental activity focuses on the hypnotic suggestions.

Others have suggested that hypnosis is not a distinct state of consciousness, but more of a role-playing exercise. Have you ever watched a little boy pretend he was a firefighter? He becomes so enthralled in his play that he really believes he is a firefighter. His tricycle is now his fire engine; his baseball cap his firefighter’s hat. He is the firefighter. Something similar happens when we are hypnotized. We have an expectation of how a hypnotized person should act or behave; therefore, our hypnotized response is nothing more than the role we think we should take on. And this is particularly true when good rapport exists between the hypnotist and the person being hypnotized.

Fade to Black?

It is time to conclude our discussion of consciousness, but first let’s run through some of the big picture concepts you should take away from this chapter. Consciousness refers to a state of awareness—awareness of self and things outside of self—that has many gradations and dimensions. During sleep, awareness decreases, but it does not fade entirely (remember that alarm clock that becomes part of your dream about a wailing siren). Sleep has many stages, but the two main forms are non-REM and REM. Dreams may serve a purpose, but they may also be nothing more than your brain’s interpretation of neurons signaling in the night. You learned from Dr. Julien that anesthetic drugs can profoundly alter consciousness. The same is true of recreational drugs, the use of which can lead to dependence, health problems, and death. Although somewhat controversial and misunderstood, hypnosis appears to induce an altered state of consciousness and may have useful therapeutic applications.

show what you know

Question 4.1

1. Match the agent in the left column with the most appropriate outcome in the right column:

| ________ 1. depressant | a. blocks pain |

| ________ 2. opioid | b. slows down activity in the CNS |

| ________ 3. alcohol | c. increases neural activity in the CNS |

| ________ 4. cocaine | d. cirrhosis of the liver |

depressant: b. slows down activity in the CNS; 2. opioid: a. blocks pain; 3. alcohol: d. cirrhosis of the liver; 4. cocaine: c. increases neural activity in the CNS

Question 4.2

2. An acquaintance described an odorless, tasteless, and colorless substance he took many years ago. He discussed a variety of changes to his sensations and perceptions, including seeing colors and spirals. It is likely he had taken which of the following hallucinogens:

- alcohol

- nicotine

- LSD

- cocaine

c. LSD

Question 4.3

3. Dr. Julien uses a variety of ________ to dull the perception of pain, to inhibit memories of surgery, and to change a variety of psychological activities.

psychoactive drugs

Question 4.4

4. People often describe behaviors as being addictive. You might hear a character in a movie say that he is addicted to driving fast, for example. These descriptions often refer to dangerous or risky behaviors. Given what you have learned about physiological and psychological dependence, how would you determine if these behaviors should be considered problematic?

To determine if behaviors should be considered problematic, one could evaluate the presence of tolerance or withdrawal, both signs of physiological dependence. With tolerance, one’s system adapts to a drug over time and therefore needs more and more of the substance to re-create the original effect. Withdrawal can occur with constant use of some psychoactive drugs, when the body has become dependent and then reacts when the drug is withheld. In some cases, with psychological dependence, behaviors may be problematic when there is a strong desire or need to continue the behavior, but with no evidence of tolerance or withdrawal symptoms. If an individual harms himself or others around him as a result of his behaviors, it is a problem. Overuse is maladaptive and causes significant impairment or distress to the user and/or his family. This might include difficulties at work or school, neglect of children and household duties, and physically dangerous behaviors.