9.1 Introduction to Motivation

motivation and emotion

FIRST DAY OF SCHOOL

Introduction to Motivation

FIRST DAY OF SCHOOL

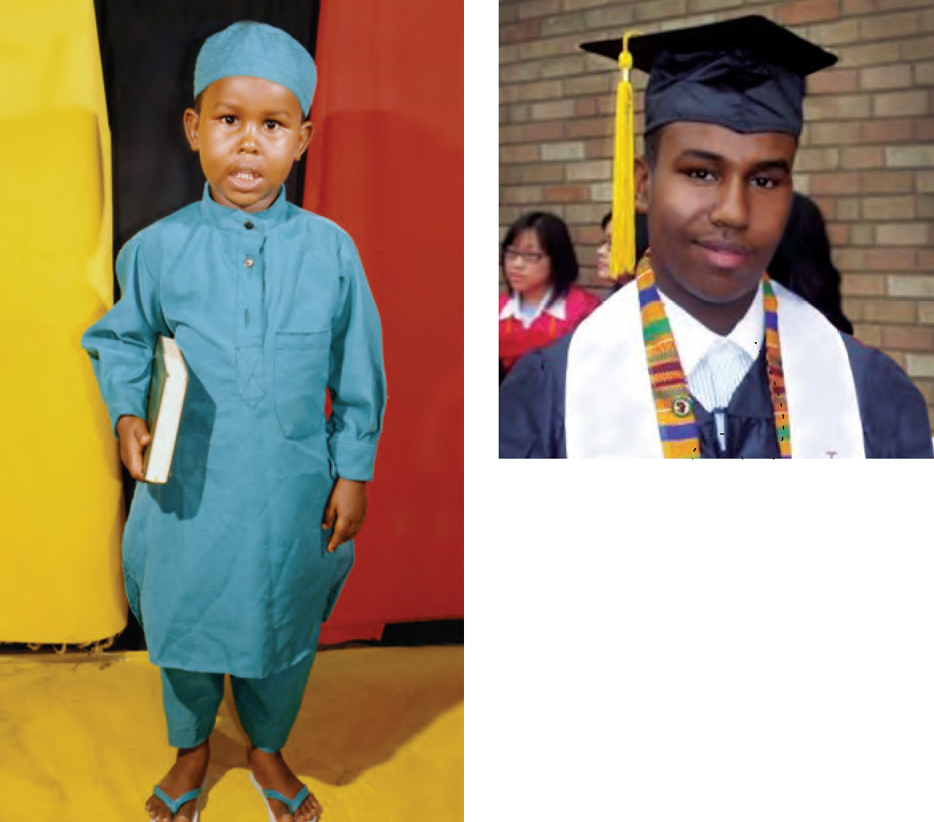

When Mohamed Dirie started first grade, he did not know his ABCs or 123s. He had no idea what the words “teacher,” “cubby,” or “recess” meant. In fact, he spoke virtually no English. As for his classmates, they were beginning first grade with basic reading and writing skills from preschool and kindergarten. Mohamed’s early education had taken place in an Islamic school, where he spent most of his time learning to read and recite Arabic verses of the Qur’an (kə-ˈrän). But Arabic wasn’t going to be much help to a 6-year-old trying to get through first grade in St. Paul, Minnesota.

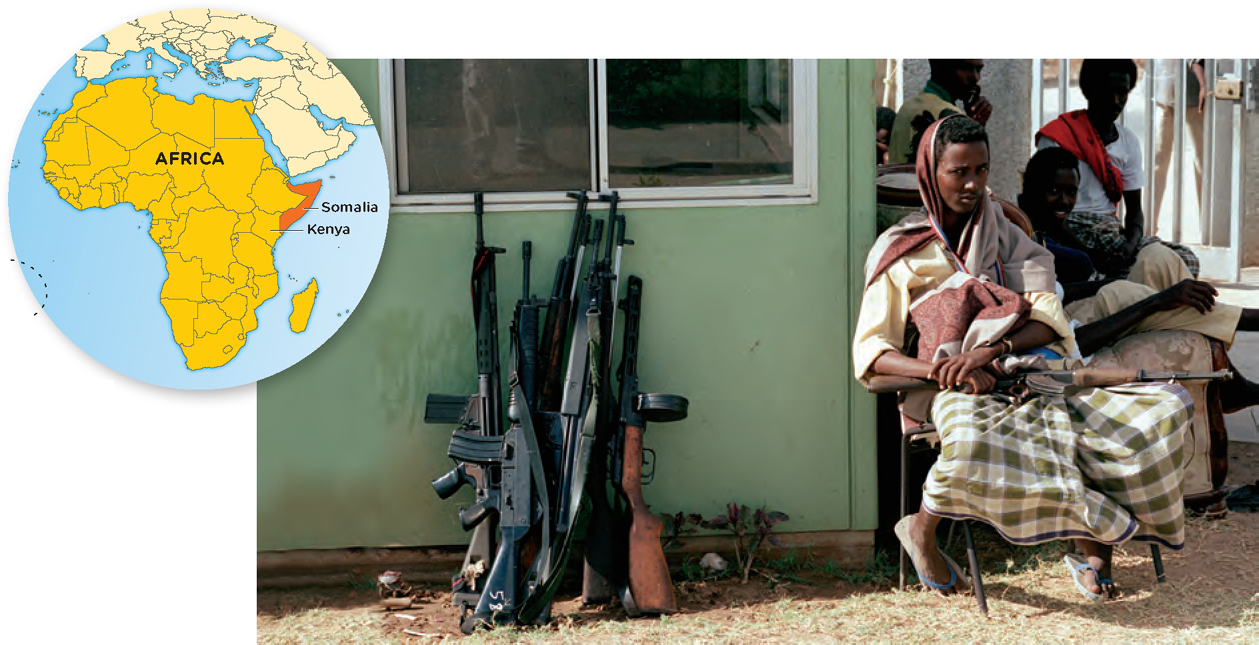

Months earlier, Mohamed and his mother, father, and older sister had arrived in St. Paul from the East African nation of Kenya, some 8,000 miles across the globe. Kenya was not their native country, just a stopping point between their homeland, Somalia, and a new life in America.

Perhaps you have heard about Somalia. Most of the news stories coming out of this nation during the past two decades have related themes of tragedy: bloody clashes between rival factions, kidnappings by pirates, suicide bombings, and starving children. Somalia’s serious troubles began in 1991 when rebel forces overthrew the government of President Siad Barre. That was the year Mohamed’s family and thousands of others fled the country, narrowly escaping death. Packed in a truck full of people, they sped away from their home city of Mogadishu as gunshots rang through the streets. And it’s a good thing they left when they did, because as of the publication of this book, Somalia is still mired in civil war.

The first day of school in St. Paul, little Mohamed strapped on his backpack and walked with his mother to the bus stop. When the yellow bus pulled up to the curb, Mohamed’s mother followed him inside and insisted on accompanying him to school. But Mohamed was ready to make the journey alone. “No, Mom, I got this,” he remembers saying in his native Somali.

When Mohamed arrived at his new school, he found his way to the first-grade classroom and discovered a swarm of children chattering and making friends. Mohamed wanted to mingle, too, so he endeared himself to the other kids the best way he could—by smiling. Flashing a grin was Mohamed’s way of communicating, Hey, I am a good person and you should get to know me. And it was a strategy that worked. “I really felt like other people approached me better,” he says. Mohamed’s warm and welcoming demeanor may have been one reason his teacher took a special interest in him, providing the individual attention he needed to catch up to his peers. And Mohamed caught up quickly.

Note: Quotations attributed to Mohamed Dirie are personal communications.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

after reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- LO 1 Define motivation.

- LO 2 Explain how extrinsic and intrinsic motivation impact behavior.

- LO 3 Summarize instinct theory.

- LO 4 Describe drive-reduction theory and explain how it relates to motivation.

- LO 5 Explain how arousal theory relates to motivation.

- LO 6 Outline Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

- LO 7 Explain how self-determination theory relates to motivation.

- LO 8 Discuss how the stomach and the hypothalamus make us feel hunger.

- LO 9 Outline the major eating disorders.

- LO 10 Define emotions and explain how they are different from moods.

- LO 11 Identify the major theories of emotion and describe how they differ.

- LO 12 Discuss evidence to support the idea that emotions are universal.

- LO 13 Indicate how display rules influence the expression of emotion.

- LO 14 Describe the role the amygdala plays in the experience of fear.

- LO 15 Summarize evidence pointing to the biological basis of happiness.

Mohamed, in his own words:

By the end of third grade, he had graduated from an English as a Second Language (ESL) program and could converse fluently with classmates. He sailed through the rest of elementary school with As and Bs in all subjects. Middle school presented new challenges, as Mohamed attended one of the poorest schools in the district and occasionally got picked on, but he continued to excel academically, taking the most challenging classes offered. In high school, he took primarily international baccalaureate (IB) or pre-IB classes, which prepped him for his undergraduate work at the University of Minnesota. Now with his bachelor’s degree in scientific and technical communication, Mohamed is contemplating his next step. Will it be law school? A master’s degree? Maybe a PhD?

If you think about where Mohamed began and where he is today, it’s hard not to be awed. He entered the United States’ school system 2 years behind his peers, unable to speak a word of English, an outsider in a culture radically different from his own. Without any tutoring from his parents (who couldn’t read the class assignments, let alone help him with schoolwork), he managed to propel himself to the upper levels of the nation’s educational system in just 12 years.

How do you explain Mohamed’s success? This young man definitely is intelligent. You can tell he is bright after 5 minutes of conversation. But intelligence is not the only ingredient in the recipe for outstanding achievement. Other factors are important as well, including something psychologists consider essential for success in school: motivation (Conley, 2012; Hodis, Meyer, McClure, Weir, & Walkey, 2011; Linnenbrink & Pintrich, 2002).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 7, we described intellectually gifted people as those with very high IQ scores. We also presented the concept of emotional intelligence. Here, we see that in addition to intelligence, motivation plays a role in success.

What Is Motivation?

Mohamed: What motivated you to go to college and better your education?

There are people who get kicks from bungee jumping from helicopters, and those who feel completely invigorated by a rousing match of chess. Human behaviors can be logical: We eat when hungry, sleep when tired, and go to work to pay the rent. Our behaviors can also be senseless and destructive: A beautiful fashion model starves herself, or an aspiring politician throws away an entire career for a fleeting sexual adventure. Why do people spend their hard-earned money on lottery tickets when the chances of winning may be 1 in 175 million (Wasserstein, 2013, May 16)? And what in the world drives teenagers to wrap houses in toilet paper on Halloween night?

One way to explain human behavior is through learning. We know that people (not to mention dogs, chickens, and slugs) can learn to behave in certain ways through classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning (Chapter 5). But learning isn’t everything. Another way to explain behavior is to consider what might be motivating it. In the first half of this chapter, you will learn about different forms of motivation and the theories explaining them. Keep in mind that human behavior is complex and should be studied in the context of culture, biology, and the environment. Every behavior is likely to have a multitude of causes (Maslow, 1943).

LO 1 Define motivation.

Psychologists propose that motivation is a stimulus or force that can direct the way we behave, think, and feel. A motivated behavior tends to be guided (that is, it has a direction), energized, and persistent. Mohamed’s academic behavior has all three features: guided because he sets specific goals like getting into graduate school, energized because he goes after those goals with zeal, and persistent because he sticks with his goals even when challenges arise.

Incentive

In this chapter, we will explain why people do the things they do using the concepts of motivators and motivation. But first, let’s take a closer look at how operant conditioning, particularly the use of reinforcers, can help us understand the relationship between learning and motivation. When a behavior is reinforced (through positive or negative reinforcers), an association is established between the behavior and its consequence. If we consider motivated behavior, this association becomes the incentive, or reason to repeat the behavior. Imagine there is a term paper you have been avoiding. You decide you will treat yourself to an hour of Web surfing for every three pages you write. Adding a reinforcer (surf time) increases your writing behavior; thus, we call it a positive reinforcer. It is the association between the behavior (writing) and the consequence (Web surfing) that transforms the Web surfing into an incentive. Before you know it, you begin to expect this break from work, which motivates you to write.

LO 2 Explain how extrinsic and intrinsic motivation impact behavior.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we introduced positive and negative reinforcers, which are stimuli that increase future occurrences of target behaviors. In both cases, the behavior becomes associated with the reinforcer. Here, we see how these associations become incentives.

Extrinsic Motivation

When a learned behavior is motivated by the incentive of external reinforcers in the environment, we would say there is an extrinsic motivation to continue that behavior (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999; TABLE 9.1). In other words, the motivation comes from consequences that are found in the environment or situation. Bagels and coffee might provide extrinsic motivation for people to attend a boring meeting. Sales commissions provide extrinsic motivation for sales representatives to sell more goods. For most people, money serves as a powerful form of extrinsic motivation.

| Intrinsic Motivation Phrases | Extrinsic Motivation Phrases | Neutral Phrases |

|---|---|---|

| Writing an enjoyable paper | Writing an extra-credit paper | Writing an assigned paper |

| Working on the computer out of curiosity | Working on the computer for bonus points | Working on the computer to meet a deadline |

| Participating in a fun project | Participating in a money-making project | Participating in a required project |

| Pursuing my personal interests in class | Pursuing an attractive reward in class | Pursuing a routine task in class |

| Working with freedom | Working for incentives | Working with pressure |

| Having options and choices | Having prizes and awards | Having pressures and obligations |

| Working because its fun | Working because I want money | Working because I have to |

| Feeling interested | Anticipating a prize | Feeling frustrated |

| Listed here are descriptions of activities that typically arouse intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, or no motivation. | ||

| SOURCE: REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION OF ELSEVIER SCIENCE/THE LANCET/JAPAN NEUROSCIENCES SOCIETY FROM LEE (2012). | ||

Intrinsic Motivation

But learned behaviors can also be motivated by personal satisfaction, interest in a subject matter, and other variables that exist within a person. When the drive or urge to continue a behavior comes from within, we call it intrinsic motivation (Deci et al., 1999). Reading a textbook because it is inherently interesting exemplifies intrinsic motivation. The reinforcers originate inside of you (learning feels good and brings you satisfaction), and not from the external environment.

Consider some of the forces motivating other behaviors. Do you exercise on a regular basis, and if so, why? If being able to show off your washboard abs is what you desire, then extrinsic motivation is sending you to the gym. If you exercise because it gives you pleasure (you like feeling “the burn,” or releasing pent-up stress), then intrinsic motivation is your fuel. What compels you to offer your seat to an older adult on a bus: Is it because you’ve been praised for helping others before (extrinsic motivation), or because it simply feels good to help someone (intrinsic motivation)? Perhaps your response is a combination of both.

Extrinsic Versus Intrinsic

Many behaviors are inspired by a blend of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation, but there do appear to be potential disadvantages to extrinsic motivation (Deci et al., 1999). Researchers have found that using rewards, such as money and marshmallows, to reinforce already interesting activities (like doing puzzles, playing word games, and so on) can lead to a decrease in what was initially intrinsically motivating. Why is this so? It could be that external reinforcers make it more difficult for people to develop self-regulation. Receiving external rewards may cause them to feel less responsible for initiating their own behaviors. In general, behavior resulting from intrinsic motivation is likely to include “high-quality learning,” but only when the activities are novel, challenging, or have aesthetically pleasing characteristics. Extrinsic motivation may be less effective, resulting in resentment or disinterest (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Unfortunately, researchers have found that “tangible rewards—both material rewards, such as pizza parties for reading books, and symbolic rewards, such as good student awards—are widely advocated by many educators and are used in many classrooms, yet the evidence suggests that these rewards tend to undermine intrinsic motivation for the rewarded activity” (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 2001, p. 15).

For Mohamed, the most powerful source of extrinsic motivation was the approval of his mother. He recalls how proud she had been after returning from a parent–teacher conference in which the first-grade teacher said, “Your child is as bright as the sun.” Mohamed doesn’t remember his mom rewarding him with material things like toys and candy; apparently, making her proud was gratifying enough. But there were also forces driving Mohamed from within (intrinsic motivation). He enjoyed the process of learning. It was rewarding to master a second language and nail down his multiplication tables. Outside of class, Mohamed read books for fun. He still enjoys reading science fiction, so much that he hopes to write his own novel one day. Says Mohamed, “I want to be the first Somali to write a science fiction [book] in Somali.”

We now have developed a basic understanding of what motivation is: a stimulus or force that can direct the way we behave, think, and feel. We also have established that motivation may stem from factors outside of ourselves (extrinsic) or from within (intrinsic). But what underlies motivation? Let’s take a look at the major theories.

show what you know

Question 9.1

1. ________ is a stimulus that directs the way we behave, think, and feel.

Motivation

Question 9.2

2. Behavior that is motivated by internal reinforcers is considered to be the result of

- extrinsic motivation.

- intrinsic motivation.

- persistence.

- external consequences.

b. intrinsic motivation.

Question 9.3

3. Imagine you are a teacher trying to motivate your students. Explain why you would want your students to be influenced by intrinsic motivation as opposed to extrinsic motivation.

Answers will vary. Extrinsic motivation is the drive or urge to continue a behavior because of external reinforcers. Intrinsic motivation is the drive or urge to continue a behavior because of internal reinforcers. A teacher wants to encourage intrinsic motivation because the reinforcers originate inside of the students, through personal satisfaction, interest in a subject matter, and so on. There are some potential disadvantages to extrinsic motivation. For example, using rewards, such as money and candy, to reinforce already interesting activities can lead to a decrease in what was intrinsically motivating. Thus, the teacher would want students to respond to intrinsic motivation because the tasks themselves are motivating, and the students love learning for the sake of learning itself.

When activities are not novel, challenging, or do not have aesthetically pleasing characteristics, intrinsic motivation will not be useful. Thus, using rewards might be the best way to motivate these types of activities.