13.2 Classifying and Explaining Psychological Disorders

How was Ross diagnosed with bipolar disorder? He consulted with a psychiatrist. But how did this mental health professional come to the conclusion that his client suffered from bipolar disorder, and not something else? Given what we know about the complexity of determining abnormal behavior, it probably comes as no surprise that clinicians have not always agreed on what qualifies as a psychological disorder. Over the years, however, they have developed common criteria and procedures for making reliable diagnoses. These criteria and decision-making procedures are presented in manuals, which are shared across mental health professions, and are based on research findings and clinical observations.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5)

Think about the last time you were ill and went to a doctor. You probably answered a series of questions about your symptoms. The nurse took your blood pressure and temperature, and the doctor performed a physical exam. Based on these subjective and objective findings, the doctor formulated a diagnosis. Mental health professionals must do the same—make diagnoses based on evidence. In addition to gathering information from interviews and other clinical assessments, psychologists typically rely on manuals to guide their diagnoses. Most mental health professionals in North America use the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5; APA, 2013). The DSM–5 is an evidence-based classification system of mental disorders first developed and published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA; www.psych.org) in 1952. This manual was conceived and designed to help ensure accurate and consistent diagnoses based on the observation of symptoms. Although the DSM is published by the American Psychiatric Association (www.psych.org)—different from the American Psychological Association, also abbreviated APA—it is used by psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and a variety of other clinicians.

DSM, Take Five

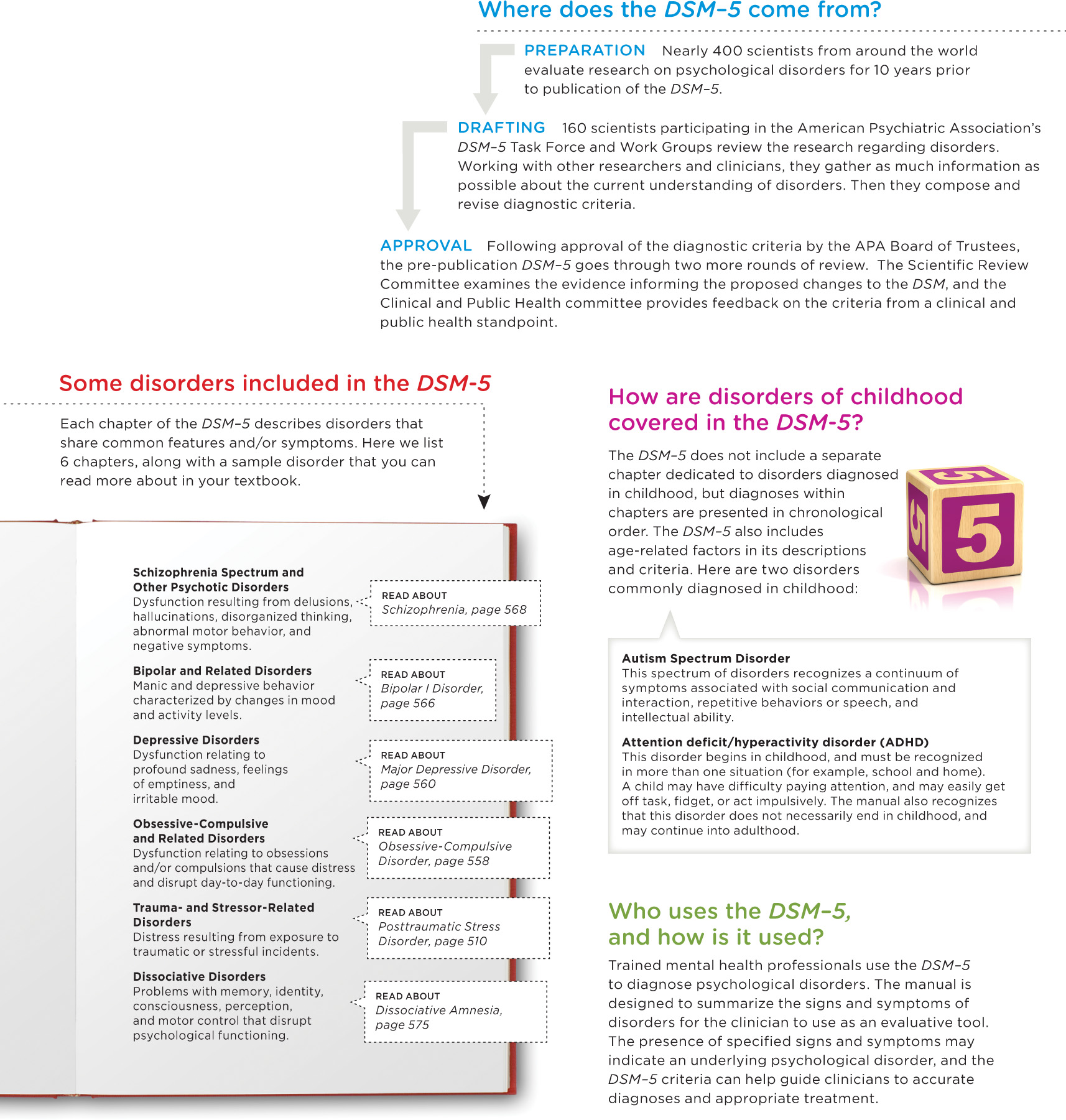

When the DSM was comprehensively revised in 1994, it included classifications for 172 psychological disorders. The DSM–5 revision lists 157 disorders (American Psychiatric Association Division of Research, personal communication, July 26, 2013) and presents some new ideas on how to think about them (Infographic 13.1). The current revision also represents a substantial shift in how the manual is organized. The psychological disorders are presented in 20 chapters, with content organized around developmental changes occurring across the life span. Some disorders were removed from the manual (sexual aversion disorder, for instance) and others were added (hoarding disorder). Another major change is that several axes, or dimensions, previously used as additional information are now integrated within the diagnostic criteria for some disorders.

Criticisms of Classification

LO 2 Recognize limitations in the classification of psychological disorders.

Why is the DSM important? Classifying mental disorders helps therapists develop treatment plans, enables clients to obtain reimbursement from their insurance companies, and facilitates research and communication among professions. But there is a downside to classification. Anytime someone is diagnosed with a mental disorder, he runs the risk of being labeled, which can lead to the formation of expectations—not only from other people, but also from himself. Few studies illustrate this phenomenon more starkly than David Rosenhan’s classic 1973 study “On Being Sane in Insane Places.”

INFOGRAPHIC 13.1: The DSM–5

Revising the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders was no small task. The process took over 10 years and involved hundreds of experts poring over the most relevant and current research. The final product helps researchers conduct studies and clinicians develop treatment plans and work with other professionals.

SOURCE: AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION, 2013.

didn’t SEE that coming

“On Being Sane in Insane Places”

What do you think would happen if you secretly planted eight completely “sane” people (no history of psychological disorders) in American psychiatric hospitals? The hospital employees would immediately identify them as “normal” and send them home … right?

What do you think would happen if you secretly planted eight completely “sane” people (no history of psychological disorders) in American psychiatric hospitals? The hospital employees would immediately identify them as “normal” and send them home … right?

In the early 1970s, psychologist David Rosenhan and seven other mentally healthy people managed to get themselves admitted to various psychiatric hospitals by faking auditory hallucinations (“I am hearing voices”), a common symptom of schizophrenia. (Such a feat would be close to impossible in this day and age, where people with documented psychological disorders struggle to obtain inpatient treatment at all; Scribner, 2001.) Upon admission, each of these pretend patients, or “pseudopatients,” immediately stopped putting on an act and began behaving like their normal selves. But within the walls of a psychiatric hospital, their ordinary behavior assumed a whole new meaning. Staff members who spotted the pseudopatients taking notes concluded it must be a symptom of their psychological disorder. “Patient engaged in writing behavior,” nurses wrote of one pseudopatient. “Nervous, Mr. X?” a nurse asked a pseudopatient who had been walking the halls out of sheer boredom (Rosenhan, 1973, p. 253).

No hospital staff member identified the pseudopatients as frauds. If anyone had them figured out, it was the other patients in the hospital. “You’re not crazy,” they would say to the pseudopatients. “You’re a journalist, or a professor. You’re checking up on the hospital” (Rosenhan, 1973, p. 252). After an average stay of 19 days (the range being 7 to 52 days), the pseudopatients were discharged, but not because doctors recognized their diagnostic errors. The pseudopatients, they determined, had gone into “remission” from their fake disorders. They were released back into society—but not without their labels.

NO HOSPITAL STAFF MEMBER IDENTIFIED THE PSEUDOPATIENTS AS FRAUDS.

Rosenhan’s study was not warmly received by all members of the psychiatric community, and some raised legitimate concerns about its methodology, results, and conclusions (Lando, 1976; Spitzer, 1975). Nevertheless, it shed light on the persistence of labels and their associated stigma.

If eight sane people could be diagnosed with serious disorders like schizophrenia, you might be wondering if psychological diagnoses are reliable or valid. We’ve come a long way since 1973, but the diagnosis of psychological disorders remains a challenge, in part because it often relies on self-reports. Evaluating complex behaviors will never be as straightforward as measuring blood pressure or running a test for strep throat.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 11, we discussed the concepts of reliability and validity in relation to the assessment of personality. Here, we refer to these same concepts when discussing a classification system for psychological disorders. We must determine if diagnoses are reliable (able to provide consistent, reproducible results) and valid (measuring what they intend to measure).

Atheoretical Approach

The DSM series tried to address this problem in 1980, by developing a checklist of observable signs and symptoms. This atheoretical approach removed the emphasis on particular theories and made it easier for mental health professionals to agree on diagnoses. But this method brought its own set of problems. Relying on checklists rather than theory tends to limit clinicians’ understanding of their patients, and the overlapping of criteria across disorders led to some individuals being overdiagnosed (McHugh & Slavney, 2012). Yet, getting the right diagnosis is critical. If one patient is feeling down due to a “life encounter,” such as the loss of a spouse, and another is feeling the same as a result of a “brain disease,” such as bipolar disorder, their treatment needs will be drastically different (McHugh & Slavney, 2012).

“Abnormal,” But Not Uncommon

You probably know someone with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Perhaps you have experienced a disorder yourself. Psychological disorders are not uncommon (TABLE 13.2). Findings from a large study of approximately 9,000 individuals indicated that around 50% of the population in the United States, at some point over the course of their lives, experience symptoms that meet the criteria of a psychological disorder (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005; Kessler & Wang, 2008). Yes, you read that correctly; “Nearly half the population meet criteria for a mental disorder in their life …” (Kessler, 2010, p. 60). The majority of these disorders begin before the age of 14. Longitudinal studies monitoring children through young adulthood indicate that psychological disorders are “very common,” with more than 70% being diagnosed by age 30 (Copeland, Shanahan, Costello, & Angold, 2011; Farmer, Kosty, Seeley, Olino, & Lewinsohn, 2013). And it’s not just Americans who struggle with these issues. Lifetime prevalence rates for major psychological disorders range from approximately 26% in Lebanon (Karam et al., 2008) to about 30% in South Africa (Stein et al., 2008), with rates in many other countries similar to those in the United States (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2008; Wittchen & Jacobi, 2005).

| Psychological Disorder | Annual Prevalence |

|---|---|

| Anxiety disorders | 18.1% |

| Specific phobia | 8.7% |

| Social phobia | 6.8% |

| Disruptive behavior disorders | 8.9% |

| Mood disorders | 9.5% |

| Major depression | 6.7% |

| Substance disorders | 3.8% |

| Any disorder | 26.2% |

| In any given year, many people are diagnosed with a psychological disorder. The numbers here represent annual prevalence: the percentage of the U. S. population affected by a disorder over a year. (Elsewhere we have referred to lifetime prevalence, which means the percentage of the population affected by a disorder anytime in life.) | |

| SOURCE: KESSLER (2010). | |

A Tough Road

With such high rates of disorders, you can be sure there are many people around you dealing with tough issues. In some cases, psychological disorders lead to greater impairment than chronic medical conditions, yet people with mental ailments are less likely to get treatment (Druss et al., 2009). Keep in mind that various psychological disorders are chronic (a person suffers from them continuously), others have a regular pattern (symptoms appear every winter, for example), and some are temporary.

Further complicating the picture is the fact that many people suffer from more than one psychological disorder at a time, a phenomenon called comorbidity  . The Kessler studies mentioned above found that around 22% of participants had received two diagnoses in the course of a year, and 23% three diagnoses (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005). You already know that one psychological disorder can lead to significant impairment; now just imagine how these problems compound with more than one disorder.

. The Kessler studies mentioned above found that around 22% of participants had received two diagnoses in the course of a year, and 23% three diagnoses (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005). You already know that one psychological disorder can lead to significant impairment; now just imagine how these problems compound with more than one disorder.

What Causes Psychological Disorders?

LO 3 Summarize the etiology of psychological disorders.

As we describe psychological disorders throughout this chapter, we will highlight some of the major theories of their etiology, or causes. But before getting into the specifics, let’s familiarize ourselves with the models commonly used to explain the etiology of psychological disorders.

It’s In Your Biology: The Medical Model

The medical model explains psychological disorders from a biological standpoint, focusing on genes, neurochemical imbalances, and problems in the brain. This medical approach has had a long and uninterrupted history, as our culture continues to view psychological disorders as illnesses. It is evident in the language used to discuss disorders and their treatment: mental illness, therapy, remission, symptoms, patients, and doctors. Some scholars criticize this approach (Szasz, 2011), in part because it fails to acknowledge how concepts of mental health and illness have changed over time and across cultures (Kawa & Giordano, 2012).

It’s In Your Mind: Psychological Factors

Another way to understand the etiology of disorders is to focus on the contribution of psychological factors. Some theories propose that cognitive factors or personality characteristics contribute to the development and maintenance of disorders. Others focus on the ways learning or childhood experiences might lay their foundation.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we presented a variety of learning theories used to explain how behavior patterns develop. Here, we see how these theories explain how abnormal behavior can be learned. Previous chapters have also discussed Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, which suggests that early experiences may pave the way for psychological disorders.

It’s In Your Environment: Sociocultural Factors

Earlier we mentioned that culture can shape definitions of “abnormal” and influence the development of psychological disorders. Social factors, like poverty and community support systems, can also play a role in the development and course of these conditions (Honey, Emerson, & Llewellyn, 2011; Lund et al., 2011).

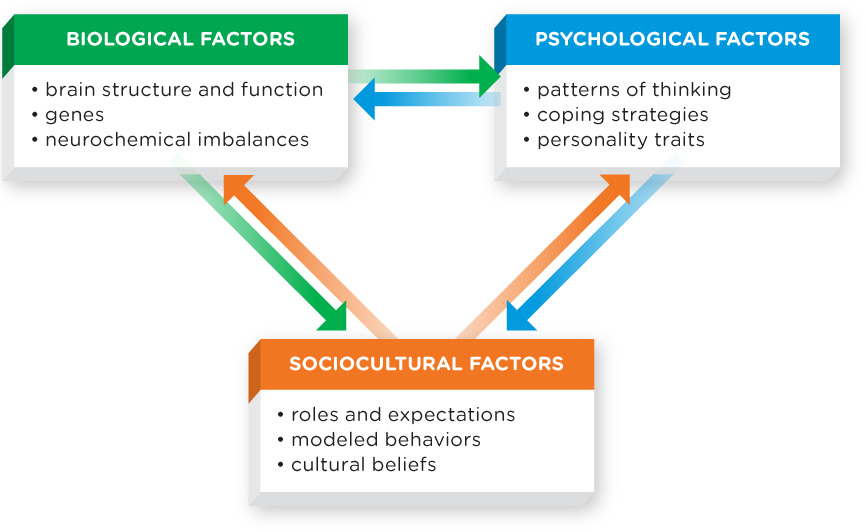

We have established that mental disorders result from a confluence of biological, psychological, and social factors. But is there a way to bring them together? Complex behaviors deserve complex explanations.

The Biopsychosocial Perspective

As we have suggested in previous chapters, the best way to understand human behavior is to examine it from a variety of perspectives. The biopsychosocial perspective provides an excellent model for explaining psychological disorders, which result from a complex interaction of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors (Figure 13.1). For example, some disorders appear to have a genetic basis, but their symptoms may not be evident until social or psychological factors come into play. We will discuss this again in the section on schizophrenia, when we take a look at the diathesis–stress model.

Now that we have a general understanding of how psychologists conceptualize psychological disorders, let’s delve into specifics. We cannot cover every disorder identified in the DSM–5, but we can offer an overview of those commonly discussed in an introductory psychology course.

CONNECTIONS

We have introduced psychological disorders in various chapters of this book. In Chapter 9, we discussed eating disorders in the context of motivation of hunger. In Chapter 10, we described sexual dysfunctions outlined in the DSM–5. And Chapter 12 explored the relationship between stressors and posttraumatic stress disorder.

UNWELCOME THOUGHTS: MELISSA’S STORY

Melissa Hopely was about 5 years old when she began doing “weird things” to combat anxiety: flipping light switches on and off, touching the corners of tables, and running to the kitchen to make sure the oven was turned off. Taken at face value, these behaviors may not seem too strange, but for Melissa they were the first signs of a psychological disorder that eventually pushed her to the edge.

Melissa Hopely was about 5 years old when she began doing “weird things” to combat anxiety: flipping light switches on and off, touching the corners of tables, and running to the kitchen to make sure the oven was turned off. Taken at face value, these behaviors may not seem too strange, but for Melissa they were the first signs of a psychological disorder that eventually pushed her to the edge.

Anxiety is a normal part of growing up. Children get nervous for an untold number of reasons: doctors’ appointments, the first day of school, or the neighbor’s German shepherd. But Melissa was not suffering from common childhood jitters. Her anxiety overpowered her physically, gripping her arms and legs in pain and twisting her stomach into a knot. It affected her emotionally, bringing on a vague feeling that something awful was about to occur—unless she did something to stop it. If I just touch all the corners of this table like so, nothing bad will happen, she would think to herself.

As Melissa grew older, her behaviors became increasingly regimented. She felt compelled to do everything an even number of times. Instead of entering a room once, she would enter or leave twice, four times, perhaps even twenty times—as long as the number was a multiple of 2. Some days she would sit in her bedroom for hours, methodically touching all of her possessions twice, then repeating the process again, and again. By performing these rituals, Melissa felt she could prevent her worst fears from becoming reality.

What was she so afraid of? Dying, losing all her friends, and growing up to be jobless, homeless, and living in a dumpster. She also feared striking out in her next softball game and making the whole team lose. Something dreadful was about to happen, though she couldn’t quite put her finger on what it was. The reality was that Melissa had little reason to worry. Neither she nor her family members were in ill-health or danger. She seemed to have everything going for her: health, smarts, beauty, and a loving circle of friends and family.

We all experience irrational worries from time to time, but Melissa’s anxiety had become overwhelming. Where does one draw the line between anxiety that is normal and anxiety that is abnormal?

show what you know

Question 13.4

1. The classification and diagnosis of psychological disorders havehe been criticized for

- having specific criteria to identify disorders.

- the creation of labeling and expectations.

- placing too much emphasis on sociocultural factors.

- their research base.

b. the creation of labeling and expectations.

Question 13.5

2. In the United States, approximately ____________ of people will meet the criteria of a psychological disorder at some point in their lives.

- 25%

- 40%

- 50%

- 75%

c. 50%

Question 13.6

3. One common approach to explaining the etiology of psychological disorders is the __________, which implies that psychological disorders have underlying biological causes, such as genes, neurochemical imbalances, and problems in the brain.

medical model

Question 13.7

4. Melissa indicated that her worries began early in life. Using the biopsychosocial perspective, speculate about the factors that may have caused and reinforced these worries.

Answers will vary, but can be based on the following information (see Figure 13.1). The biopsychosocial perspective suggests that psychological disorders result from a complex interaction of factors: biological (for example, neurotransmitters, hormones), psychological (for example, thinking, coping, personality traits), and sociocultural (for example, media, cultural beliefs).