14.3 Behavior Therapies

Get to Work! Behavior Therapy

LO 6 Describe the concepts that underlie behavior therapy.

The most famous baby in the history of psychology is probably Little Albert. At the age of 11 months, Albert developed an intense fear of rats while participating in a classic study conducted by John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner (1920). You may wonder whether the researchers ever attempted to reverse the effects of their ethically questionable experiment. Did they do anything to help Albert overcome his fear of rats? As far as we know, they did not. But we can’t help but wonder whether Albert could have been helped with behavior therapy.

Using the learning principles of classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning (Chapter 5), behavior therapy aims to replace maladaptive behaviors with those that are more adaptive. If behaviors are learned, who says they can’t be changed through the same mechanisms? Little Albert learned to fear rats, so perhaps he could also learn to be comfortable around them.

Exposure and Response Prevention

To help a person overcome a fear or phobia, a behavior therapist might use exposure, a technique of placing clients in the situations they fear—without any actual risks involved. Take, for example, a client struggling with a rat phobia. Rats cause this person extreme anxiety; the mere thought of seeing one scamper beneath a dumpster causes great distress. The client usually goes to great lengths to avoid the rodents, and this makes his anxiety drop. This reduced anxiety (and the satisfaction associated with it) will negatively reinforce his avoidance behavior. With exposure therapy, the therapist might arrange for the client to be in a room with a very friendly pet rat. After a positive experience with the animal, the client’s anxiety diminishes (along with his efforts to avoid it), and he learns the situation does not have to be anxiety provoking. Ideally, both the anxiety and the avoidance behavior are extinguished. This process of stamping out learned associations is called extinction. The theory behind this response prevention technique is that if you encourage someone to confront a feared object or situation, and prevent him from responding the way he normally does, the fear response eventually diminishes or disappears.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we learned about negative reinforcement; behaviors followed by a reduction in something unpleasant are likely to recur. If anxiety is reduced as a result of avoiding a feared object, the avoidance will be repeated.

A particularly intense form of exposure is to flood a client with an anxiety- provoking stimulus that she cannot escape, causing a high degree of arousal. In one study, for example, women with snake phobias sat in very close proximity to a garter snake in a glass aquarium for 30 minutes without a break (Girodo & Henry, 1976).

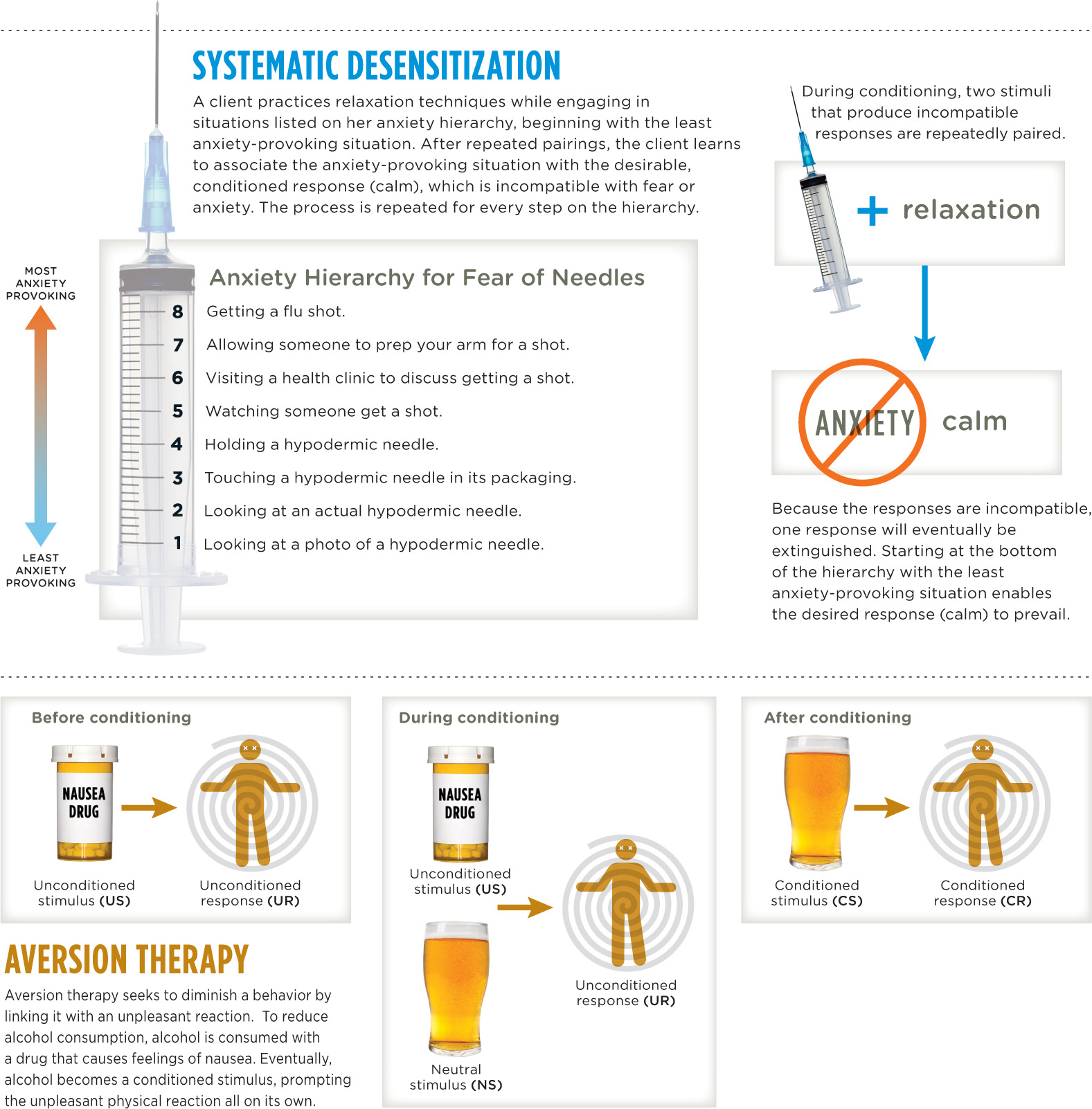

But sometimes, it’s better to approach a feared scenario with “baby steps,” upping the exposure with each movement forward (Prochaska & Norcross, 2014). This can be accomplished with an anxiety hierarchy, which is essentially a list of activities or experiences ordered from least to most anxiety provoking (Infographic 14.2). For example, Step 1: Think about a caged rat; Step 2: Look at a caged rat from across the room; Step 3: Walk two steps toward the cage, and so on.

But take note: Working up the anxiety hierarchy needn’t involve actual rodents. With technologies available today, you could put on some fancy goggles and travel into a virtual “rat world” where it is possible to reach out and “touch” that creepy crawly animal with the simple click of a rat, er…mouse. Virtual reality exposure therapy has become a popular way of reducing anxiety associated with various disorders, including specific phobias. Let’s see how it works.

didn’t SEE that coming

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy

Imagine you are 1 of the 19 million Americans suffering from a specific phobia (Kessler et al., 2005). The object of your phobia does not happen to be rats, snakes, or anything with a heartbeat, but something that zooms through the clouds at 500 miles per hour. You suffer from aviaphobia, or fear of airplane travel. The idea of flying makes you so anxious that you haven’t stepped in a plane in years. In fact, your phobia has prevented you from taking your dream trip to Mexico, and you are tired of being afraid. So you consult a therapist, who develops a treatment plan incorporating virtual reality exposure therapy. Are you ready to fly the virtual skies?

Imagine you are 1 of the 19 million Americans suffering from a specific phobia (Kessler et al., 2005). The object of your phobia does not happen to be rats, snakes, or anything with a heartbeat, but something that zooms through the clouds at 500 miles per hour. You suffer from aviaphobia, or fear of airplane travel. The idea of flying makes you so anxious that you haven’t stepped in a plane in years. In fact, your phobia has prevented you from taking your dream trip to Mexico, and you are tired of being afraid. So you consult a therapist, who develops a treatment plan incorporating virtual reality exposure therapy. Are you ready to fly the virtual skies?

Wearing a helmetlike apparatus known as a head mounted display (HMD), you are suddenly transported into the virtual interior of a jumbo jet: The rows of blue seats, the luggage compartments overhead, and the tray table on the seat in front of you all seem so real. So, too, do the sounds of the flight attendant’s voice and the rumble of the engine, thanks to the woofer situated beneath your seat (Rothbaum, Hodges, Smith, Lee, & Price, 2000). Turn your head to the side or look toward the ceiling, and the HMD’s computer automatically adjusts to show you the part of the “plane” you are viewing. The surroundings are so realistic that you almost forget you’re sitting on a chair in a therapist’s office.

A few feet away, your therapist sits at her desk clicking away at a computer keyboard; she is moving you through the virtual airplane and monitoring your anxiety levels along the way (Krijn, Emmelkamp, Olafsson, & Biemond, 2004). Now it’s time for you to buckle your seatbelt. Once that is accomplished, prepare yourself for takeoff. If you’re really feeling comfortable, your therapist might simulate some turbulence or a bumpy landing. With enough virtual reality trials and your regular therapy, you just might be ready for that flight to Mexico.

VIRTUAL REALITY EXPOSURE THERAPY SOUNDS LIKE A GREAT IDEA, BUT DOES IT WORK?

Virtual reality exposure therapy sounds like a great idea, but does it work? Studies suggest that this method is effective for treating various phobias, including aviaphobia, arachnophobia (fear of spiders and similar insects), and social phobia (Parsons & Rizzo, 2008), though further research is needed to determine how good it is as a stand-alone treatment. As Krijn and colleagues (2004) point out, virtual reality exposure therapy is usually combined with other forms of therapy, and in the case of aviaphobia, this approach may be just as effective as regular exposure therapy (Rothbaum et al., 2000). It’s certainly a lot more practical than using a real plane.

Systematic Desensitization

Therapists often combine anxiety hierarchies with relaxation techniques in an approach called systematic desensitization, which takes advantage of the fact that we can’t be relaxed and anxious at the same time. The therapist begins by teaching clients how to relax their muscles. One technique for doing this is progressive muscle relaxation, which is the process of tensing and then relaxing muscle groups, starting at the head and ending at the toes. Using this method, a client can learn to release all the tension in his body. It’s very simple—want to try it?

try this

Sit in a quiet room in a comfortable chair. Start by tensing the muscles controlling your scalp: Hold that position for about 10 seconds and then release, focusing on the tension leaving your scalp. Next follow the same procedure for the muscles in your face, tensing and releasing. Continue all the way down to your toes and see what happens.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 12, we described progressive muscle relaxation in the context of reducing the impact of responses to stress. Here, we see it can also be used to help with the treatment of phobias.

Once a client has learned how to relax, it’s time to face the anxiety hierarchy (either in the real world or via imagination), while trying to maintain a sense of calm. Imagine a client who fears flying, moving through an anxiety hierarchy with her therapist. Starting with the least-feared scenario at the bottom of her hierarchy, she imagines purchasing a ticket online. If she can stay relaxed through the first step, then she moves to the second item in the hierarchy, thinking about boarding a plane. At some point in the process, she might start to feel jittery or unable to take the next step. If this happens, the therapist guides her back a step or two in the hierarchy, or as many steps as she needs to feel calm again, using the relaxation technique described above. Then it’s back up the hierarchy she goes. It’s important to note that this process does not happen in one session, but over the course of many sessions.

Aversion Therapy

Exposure therapy focuses on extinguishing or eliminating associations, but there is another behavior therapy aimed at producing them. It’s called aversion therapy. Seizing on the power of classical conditioning, aversion therapy seeks to link problematic behaviors, such as alcohol overuse, drug use, or fetishes, to unpleasant physical reactions like sickness and pain (Infographic 14.2). The goal of aversion therapy is to get people to have an involuntary unpleasant physical reaction to an undesired behavior, so that eventually the undesired behavior becomes a conditioned stimulus to the conditioned response of feeling bad. A good example is the drug Antabuse, which has helped some people with alcoholism stop drinking, at least temporarily (Cannon, Baker, Gino, & Nathan, 1986; Gaval-Cruz & Weinshenker, 2009). Antabuse interferes with the body’s ability to break down alcohol, so combining it with even a small amount of alcohol brings on an immediate unpleasant reaction (vomiting, throbbing headache, and so on). With repeated pairings of alcohol consumption and physical misery, drinkers are less inclined to drink in the future. But aversion therapies like this are only effective if the client is motivated to change and comply with treatment.

CONNECTIONS

Classical conditioning, presented in Chapter 5, can be used to reduce alcohol consumption. Drinking alcohol is a neutral stimulus to start (one drink does not normally cause vomiting). Drinking is paired with a nausea inducing drug, which is an unconditioned stimulus that causes an unconditioned response of vomiting. After repeated pairings, drinking alcohol becomes the conditioned stimulus, and the vomiting becomes the conditioned response.

Conditioning, Learning, and Therapy

Another form of behavior therapy is behavior modification, which draws on the principles of operant conditioning, shaping behaviors through reinforcement. Therapists practicing behavior modification use positive and negative reinforcement, as well as punishment, to help clients increase adaptive behaviors and reduce those that are maladaptive. For behaviors that resist modification, therapists might use successive approximations by reinforcing incremental changes. Some will incorporate observational learning (that is, learning by imitating and watching others) to help clients change their behaviors.

In Chapter 5, we described how positive reinforcement (supplying something desirable) increases the likelihood of a behavior being repeated. Therapists use reinforcement in behavior modification to shape behaviors to be more adaptive.

INFOGRAPHIC 14.2: Classical Conditioning in Behavior Therapies

Behavior therapists believe that most behaviors—either desirable or undesirable—are learned. When a behavior is maladaptive, a new, more adaptive behavior can be learned to replace it. Behavior therapists use learning principles to help clients eliminate unwanted behaviors. The two behavior therapies highlighted here rely upon classical conditioning techniques. In exposure therapy, a therapist might use an approach known as systematic desensitization to reduce an unwanted response, such as a fear of needles, by pairing it with relaxation. In aversion therapy, an unwanted behavior such as excessive drinking is paired with unpleasant reactions, creating an association that prompts avoidance of that behavior.

One common approach using behavior modification is the token economy, which harnesses the power of positive reinforcement to encourage good behavior. Token economies have proven successful for a variety of populations, including psychiatric patients in residential treatment facilities and hospitals, children in classrooms, and convicts in prisons (Dickerson, Tenhula, & Green-Paden, 2005; Kazdin, 1982). In a residential treatment facility, for example, patients with schizophrenia may earn tokens for socializing with each other, cleaning up after themselves, and eating their meals. Tokens can be exchanged for candy, outings, privileges, and other perks. They can also be taken away as a punishment to reduce undesirable behaviors. Critics contend that token economies manipulate and humiliate the people they intend to help (you might agree that giving grown men and women play money for good behavior is degrading). But, from a practical standpoint, these systems can help people adopt healthier behaviors.

CONNECTIONS

Tokens are an excellent example of a secondary reinforcer. In Chapter 5, we reported that secondary reinforcers derive their power from their connection with primary reinforcers, which satisfy biological needs.

Unlike the reward systems parents might use to encourage good behavior at home, token economies tend to be implemented in institutions, such as schools. Dr. Foster, for example, sometimes works with children who are acting out in the classroom. To reinforce positive behaviors, he might arrange for a school counselor or teacher’s aide to provide rewards such as candies, stickers, the privilege of handing out papers, or whatever happens to be reinforcing for that particular child.

Taking Stock: An Appraisal of Behavior Therapy

Behavior therapy covers a broad range of treatment approaches that share a long history. Instead of focusing on unobservable constructs (such as thinking and emotion), this approach focuses on observable behaviors occurring in the present moment. As such, it offers a few key advantages over insight therapies. Behavior therapy tends to work fast, producing quick resolutions to stressful situations, some of which may be resolved in a single session (Ollendick et al., 2009; Öst, 1989). And reduced time in therapy typically translates to a lower cost. What’s more, the procedures used in behavior therapy are often easy to operationalize (remember, the focus is on modifying observable behavior), so evaluating the outcome of therapy is more straightforward.

Behavior therapy has its drawbacks, of course. The focus is changing learned behaviors, but not all behaviors are learned (you can’t “learn” to have hallucinations). And because the reinforcement comes from an external source, newly learned behaviors may disappear when reinforcement stops. Finally, the emphasis on observable behavior may downplay the social, biological, and cognitive roots of psychological disorders. This narrow approach works well for treating phobias and other clear-cut behavior problems, but not as well for addressing far-reaching, complex issues arising from disorders such as schizophrenia.

show what you know

Question 14.8

1. The primary goal of __________ therapy is to replace maladaptive behaviors with more adaptive ones.

- behavior

- exposure

- humanistic

- psychodynamic

a. behavior

Question 14.9

2. Therapists will often help a client develop a(n) __________, which includes a list of stimuli ordered from least to most anxiety-provoking.

anxiety hierarchy

Question 14.10

3. The goal of __________ is to get people to have an involuntary unpleasant physical reaction to an undesirable behavior.

- exposure therapy

- aversion therapy

- systematic desensitization

- extinction

b. aversion therapy

Question 14.11

4. Imagine you are working in a treatment facility for children, and one of the residents has begun throwing objects at others during quiet time. Using the principles of operant conditioning and observational learning, how might you use behavior modification to change this behavior?

Answers will vary, but may be based on the following information. In behavior modification, one uses positive and negative reinforcement, as well as punishment, to help a child increase adaptive behaviors and reduce those that are maladaptive. For behaviors that resist modification, therapists might use successive approximations by reinforcing incremental changes. Some therapists will incorporate observational learning (that is, learning by imitating and watching others) to help clients change their behaviors.