15.2 Social Cognition

THE DATING GAME

The story of Joe and Susanne begins right around Valentine’s Day 2006, when Joe decided to sign up for a full membership to Match.com. A couple of days after joining the site, he noticed that an intriguing woman was checking out his profile. Susanne was just returning to the Internet dating scene after breaking off an 8-month relationship with someone she had met online.

The story of Joe and Susanne begins right around Valentine’s Day 2006, when Joe decided to sign up for a full membership to Match.com. A couple of days after joining the site, he noticed that an intriguing woman was checking out his profile. Susanne was just returning to the Internet dating scene after breaking off an 8-month relationship with someone she had met online.

While browsing through Match.com, Susanne came across Joe’s page. “I thought he was cute,” she says. “That was obviously the reason why I originally opened it.” Joe was a burly guy with a dynamite smile, and Susanne was drawn to big, teddy bear types. Reading his profile, she was immediately intrigued. “The fact that he was a single parent, you know, kind of piqued my interest,” she says. Before long, Joe was checking out Susanne’s page, liking what he saw, and he initiated the e-mail exchange that ultimately led to that first date at Chili’s.

Attributions

LO 2 Describe social cognition and how we use attributions to explain behavior.

Put yourself in Joe or Susanne’s position. There you are on Match.com, looking at the profile page of someone you find attractive. On a conscious level, you are tallying up all the interests you have in common and scrutinizing every self-descriptive adjective this person has chosen. There is also some information processing happening outside of your awareness. You might not even realize that this person reminds you of someone you know, like your mother or father, and that sense of familiarity makes you more inclined to reach out. Will you contact this person?

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 14, we described psychoanalysis, one goal of which is to increase awareness of unconscious conflicts. Here, we discuss social cognition, and how it can influence behaviors. Therapists can help clients see how some of their choices in social situations might be driven by unconscious social cognitions.

Whatever your decision may be, it is very much reliant on social cognition—the way you think about others, attend to social information, and use this information in your life, both consciously and unconsciously. Joe and Susanne used social cognition in forming first impressions of one another. You use social cognition anytime you try to interpret or respond to another person’s behavior. Let’s take a closer look at two critical facets of social cognition: attributions and attitudes.

In Chapter 10, we reported that there are gender differences in some of the brain networks involved in social cognition. Gender is an important variable to consider when evaluating how people think about others and attend to social information.

In Chapter 7, we defined cognition as the mental activity associated with obtaining, storing, converting, and using knowledge. Thinking is a specific type of cognition that involves coming to a decision, forming a belief, or developing an attitude. In this section, we examine how cognition and thinking affect the way we use social information.

Types of Attributions

LO 3 Explain how attributions lead to mistakes about the causes of behaviors.

Joe and Susanne’s courtship did not involve game playing or guesswork. Their relationship has always been fairly open, with Joe rarely wondering what Susanne is thinking and vice versa. This is usually not the case with online dating, or any kind of dating for that matter. The “dating game” typically involves a lot of guesswork about the other person’s behavior: Why didn’t he call back? What did she mean by that :-) yesterday? These kinds of questions have relevance for all human relationships, not just the romantic kind. Just think about how much time you spend wondering why people do the things that they do. The “answers” you come up with to resolve these questions are called attributions.

Attributions are beliefs we develop to explain human behaviors and characteristics, as well as situations. “Why is my friend in such a bad mood?” you might ask yourself. Your attribution might be, “Maybe he just got some bad news” or “Perhaps he is hungry.” When psychologists characterize attributions, they use the term observer to identify the person making the attribution, and actor to identify the person exhibiting a behavior of interest. If Joe was trying to explain why Susanne had checked out his profile page, then Joe is the observer and Susanne is the actor.

Attributional Dimensions

There are many types of attributions, and differentiating among them is quite a task. To make things more manageable, psychologists often describe attributions along three dimensions: controllable–uncontrollable, stable–unstable, and internal–external. Let’s see how these might apply to attributions relating to Joe and Susanne:

Controllable–uncontrollable dimension: Suppose Susanne had been 15 minutes late to meet Joe at Starbucks. If Joe assumed it happened because she got stuck in unavoidable traffic, we would say he was making an uncontrollable attribution. (As far as he knows, Susanne has no control over the traffic.) If, however, Joe assumed that Susanne’s lateness resulted from factors within her control, such as how fast she drove or what time she left her house, then the attribution would be controllable.

Stable–unstable dimension: Why did Joe cook Susanne a delicious dinner of pork chops? Susanne could infer his behavior stems from a longtime interest in cooking. This would be an example of a stable attribution. With stable attributions, the cause is long-lasting. If she thought Joe’s behavior resulted from a transient inspiration from watching a really good cooking show, then her attribution would be unstable. With unstable attributions, the cause is temporary.

Internal–external dimension: Why did Joe have trouble meeting nice single women before Susanne entered his life? If it was because there were few single women living in his immediate area, this would be an external attribution, because the cause of the problem resides outside of Joe. External attributions are commonly referred to as situational attributions, as the causes reside in the environment. If, however, Joe had trouble meeting women because he was reluctant to attend singles events, this would be an internal attribution—the cause is within Joe. For internal attributions, the cause is located inside the person, such as an illness, skill, or attitude.

Dispositional attributions are a particular type of internal attribution in which the presumed causes are traits or personality characteristics. Here, we refer to a subset of internal attributions that are deep-seated, enduring characteristics, as opposed to those that are more transient, like having the flu. If Joe had trouble meeting other singles because he has a shy, reserved personality (not actually the case, but let’s assume for the sake of example), this would be a dispositional attribution.

When people make attributions, they are often guessing about the causes of events or behaviors, and this of course leaves plenty of room for error. This is particularly true with situational and dispositional attributions. Let’s take a look at four of the most common mistakes (Infographic 15.1).

Fundamental Attribution Error

Suppose you are checking out some profiles on a dating Web site. You see someone cute and reach out with;-) (a “wink”), but never hear back. If you fall prey to the fundamental attribution error, you might automatically assume the person’s failure to respond results from her shyness (a dispositional attribution), but the real reason might be that her Internet is down (situational attribution). This is a common tendency; we often think that the cause of other people’s behaviors is a characteristic of them (a dispositional attribution) as opposed to the environment (a situational attribution) (Ross, 1977; Ross, Amabile, & Steinmetz, 1977). We easily forget that situational factors can have a powerful effect on behavior, and assume that behaviors are the consequence of a person’s disposition (Jones & Harris, 1967). When thinking about what causes or controls behavior, we “underestimate the impact of situational factors and … overestimate the role of dispositional factors” (Ross, 1977, p. 183).

How do you think this happens? One suggestion is that we have a tendency to make quick decisions about others, often by labeling them as being certain types of people. Imagine how dangerous this could be in a medical setting, when doctors and nurses need to make quick choices about treatment. A nurse seeing a patient who has slurred speech, can’t walk, and is aggressive might assume he is drunk and an “alcoholic,” ignoring other situational factors that might be involved, such as homelessness and severe dehydration (Levett-Jones et al., 2010). Similarly, a doctor might take one look at a patient and decide he is uncooperative, dirty, and just “another homeless hippie,” when in fact the patient is on the verge of a diabetic coma. Doctors should be careful not to let negative stereotypes color their diagnoses, and patients and their families should recognize that doctors are not immune to these types of attribution errors (Groopman, 2008).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 7, we described heuristics, which are used to solve problems and make decisions. But heuristics are not always reliable. Here, we see how the fundamental attribution error can lead to errors in clinical reasoning. Critical thinking takes effort and time, so it is not unusual to depend on cognitive shortcuts.

Another reason people attribute behaviors to dispositions rather than to situations is that they tend to have much more information about themselves than they do about others. Yet we must make do with the information we have—even if that information is biased and based on our own values and belief systems (Callan, Ferguson, & Bindemann, 2013). This is evident in the just-world hypothesis.

Just-World Hypothesis

People who believe the world is a fair place tend to expect that “bad things” happen for a reason. Their thinking is that when someone is “bad,” it should be no surprise when things don’t go well for him (Riggio & Garcia, 2009). Many people blame the actor in this way by applying the just-world hypothesis, which assumes that if someone is suffering, he must have done something to deserve it (Rubin & Peplau, 1975). In one study, researchers told a group of participants about a man who was violent with his wife, slapping and yelling at her. Another group heard about a loving man who gave his wife flowers and frequently made her dinner. Participants who heard about the “bad person” were more likely to predict a bad outcome for him (he will have a “terrible car accident”) than those who heard about the “good person” (he will win a “hugely successful business contract”) (Callan et al., 2013).

This just-world tendency, to some degree, may result from cultural teachings. Children in Western cultures are taught this concept so that they learn how to behave properly, show respect for authority figures, and delay gratification (Rubin & Peplau, 1975). For example, in the original tale of Cinderella (Grimm & Grimm, 1884), doves rest on Cinderella’s shoulders prior to her wedding to the Prince. As the bridal party enters and leaves the church, the doves poke out her evil stepsisters’ eyes—a punishment for being cruel to Cinderella. Through this tale, children learn that the stepsisters got what they deserved.

How does the just-world belief affect our responses to the fortune or misfortune of others? Would a strong belief in a just world inspire someone to help those living in poverty? Many people would answer yes, because they think of “just” as “fair,” and fair as “equality.” But a person who relies on the just-world hypothesis would assume the poor are poor because they deserve to be.

Self-Serving Bias

The tendency to attribute one’s successes to internal characteristics and one’s failures to environmental factors is known as the self-serving bias. Before meeting Joe, Susanne dated a guy who tended to blame his failures on external circumstances. If he lost his job, it was because the boss never liked him—not because his performance fell short. This “woe is me” attitude annoyed Susanne, who had learned to take responsibility for what happened in her life. As her mother often told her, “You can be a survivor, or you can be a victim.” Susanne’s ex-boyfriend appears to have suffered from self-serving bias.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapters 11 and 12, we introduced the concept of internal locus of control, which refers to the tendency to feel in control of one’s life. People with an internal locus tend to make choices that are better for their health. The self-serving bias represents beliefs regarding an internal locus of control for successes.

You might be surprised to learn that therapists can also fall prey to this bias (Murdock, Edwards, & Murdock, 2010). When clients end their psychotherapy earlier than therapists recommend, therapists tend to think the causes are due to the client’s situation (lack of finances) or something within the client (resistance to change), as opposed to some factor within themselves (the therapist). But when considering the same situation for another therapist, they tend to identify the opposite pattern, blaming the other therapist for the early termination of therapy.

false-consensus effect

When trying to decipher the causes of other people’s behaviors, we overrely on knowledge about ourselves. This can lead to the false-consensus effect, which is the tendency to overestimate the degree to which people think or act like we do (Ross, Greene, & House, 1977). The opposite is also true; when others do not share our thoughts and behaviors, we tend to believe they are acting abnormally or inappropriately. This false-consensus effect is evident in our beliefs about everything from celebrities—Since I love Jeremy Lin, you should, too—to adolescent substance use—I like to use drugs, you should, too (Bui, 2012; Henry, Kobus, & Schoeny, 2011). We seem to make this mistake because we have an overabundance of information about ourselves, and often limited information about others. Struggling to understand those around us, we fill in the gaps with what we know about ourselves.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 7, we describe how the availability heuristic is used to predict the probability of something happening in the future based on how easily we can recall a similar event from the past. The false-consensus effect is a special type of this heuristic; our judgments about the degree to which others think or act like we do seem to be based on this availability heuristic.

Attribution errors may lead us astray, but we can minimize their impact by being aware of our tendency to fall back on them. Now it’s time to explore another facet of social cognition. Where did you get that attitude?

Attitudes

In the last section, we discussed attributions, the explanations people create to make sense of what they observe in other people and the environment. Attributions play an important role in online dating, but there is a lot more to dating than making inferences about behaviors. For many people, including Joe and Susanne, the purpose of Internet dating is to find someone who shares common values, interests, and lifestyle choices—all variables that are strongly influenced by attitudes.

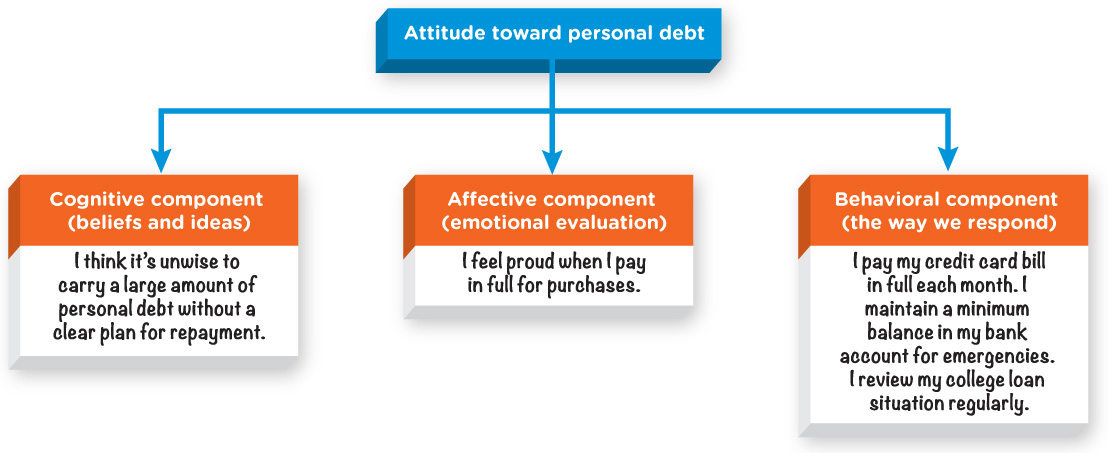

Attitudes are the relatively stable thoughts, feelings, and responses we have toward people, situations, ideas, and things (Ajzen, 2001; Wicker, 1969). Psychologists suggest that attitudes are composed of cognitive, affective, and behavioral components (Figure 15.2). The cognitive aspect of an attitude refers to your beliefs or ideas about an object, person, or situation. Generally, our attitudes include an emotional evaluation, which is the affective component relating to mood or emotion. We often have feelings that are positive or negative regarding objects, people, or situations (Ajzen, 2001). Feelings and beliefs guide the behavioral aspect of the attitude, or the way we respond. There are also instances of the opposite effect, when behavior influences feelings or beliefs, a topic we will revisit in a little while.

INFOGRAPHIC 15.1: Errors in Attribution

Attributions are beliefs we develop to explain human behaviors and characteristics, as well as situations. We can explain behaviors in many ways, but social psychologists often compare explanations based on traits or personality characteristics (dispositional attributions) to explanations based on external situations (situational attributions). But as we seek to explain events and behaviors, we tend to make predictable errors, making the wrong assumption about why someone is behaving in a certain way. Let’s look at four of the most common types of errors in attribution.

Where Do Attitudes Come From?

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we described classical conditioning and how it might instill emotions and attitudes toward product brands. Observational learning can lead children to imitate others, including their attitudes.

That being said, genetic factors do play a role. But to what degree? One of the best ways to gauge the relative weights of nature and nurture is through the study of twins. If nature has a substantive effect on attitudes, then the following should be true: Identical twins (who have the same genetic make-up) should have more similar attitudes than fraternal twins (who share about 50 percent of their genes). Let’s take a look at some of the research to see if this is the case.

In Chapter 7, we explored the heritability of intelligence. Heritability is the degree to which hereditary factors are responsible for differences across a variety of physical and psychological characteristics. Heritability research often involves comparing identical and fraternal twins, as is the case here regarding attitudes.

Of all the nature–nurture conversations occurring in the field of psychology, there is at least one arena where nurture seemingly appears to dominate: attitudes. Our attitudes develop through experiences and interactions with the people in our lives, and even through exposure to media (via classical conditioning and observational learning).

nature AND nurture

Why the Attitude?

How do you feel about rollercoasters? How about alcohol consumption? Where do you stand on the death penalty? These are just a few of the attitude topics researchers have explored in the context of nature and nurture. One study of several hundred pairs of twins concluded that most of the attitude variation among participants resulted from nonshared environmental factors, or distinct life experiences. But a significant proportion of attitude differences—35 percent—was related to genes. Those that correlated most strongly with genes centered on abortion, the death penalty, playing sports, riding rollercoasters, and reading books (Olson, Vernon, Harris, & Jang, 2001).

How do you feel about rollercoasters? How about alcohol consumption? Where do you stand on the death penalty? These are just a few of the attitude topics researchers have explored in the context of nature and nurture. One study of several hundred pairs of twins concluded that most of the attitude variation among participants resulted from nonshared environmental factors, or distinct life experiences. But a significant proportion of attitude differences—35 percent—was related to genes. Those that correlated most strongly with genes centered on abortion, the death penalty, playing sports, riding rollercoasters, and reading books (Olson, Vernon, Harris, & Jang, 2001).

Does this mean that each of us is born with a “pro-life” or “pro-choice” gene, and yet another gene that determines how we feel about sports? Highly unlikely. As the researchers point out, genes probably exert their effects indirectly, through personality traits and other genetically determined characteristics. For example, someone who is born with a very athletic physique (muscular frame or quick reaction time, for example) may become fond of sports simply because she is so good at them (Olson et al., 2001). In this case, the physical traits mediate the relationship between genes and attitudes. Attitudes can change, but genes are very stable.

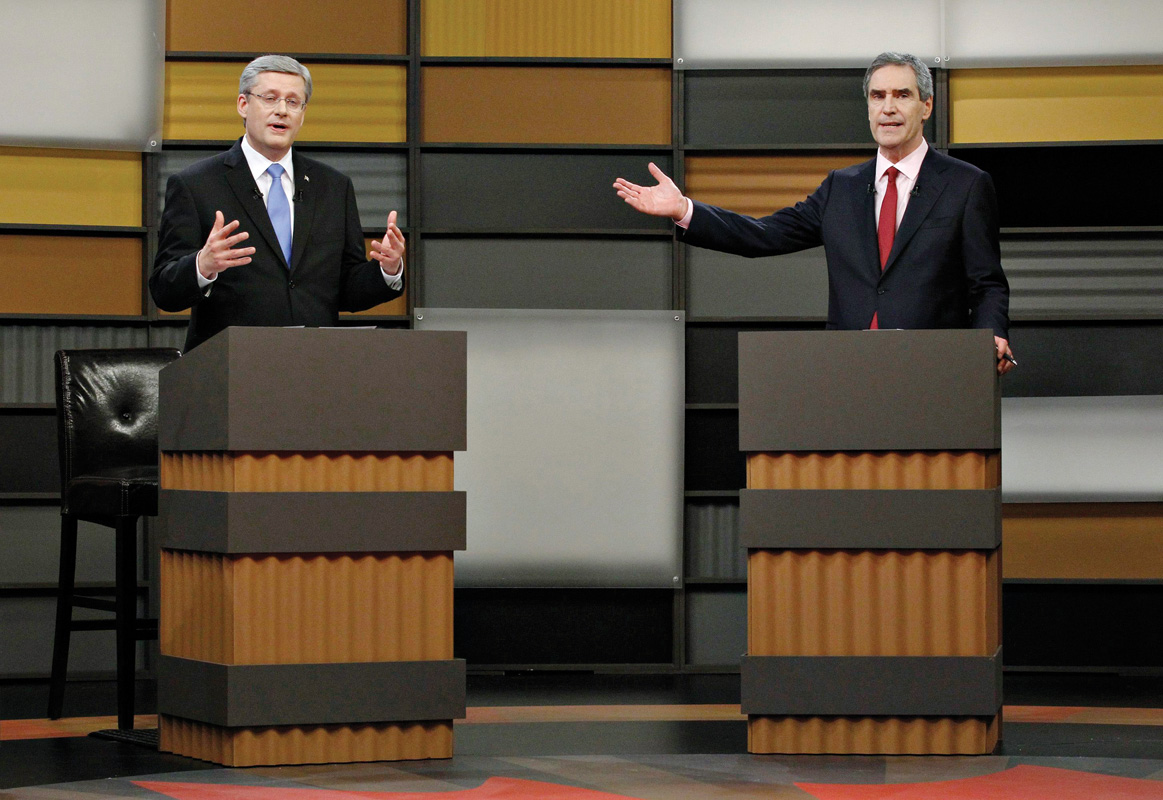

DOES THIS MEAN … EACH OF US IS BORN WITH A “PRO-LIFE” OR “PRO-CHOICE” GENE?

More recent research, also involving twins, offers evidence that political attitudes are influenced by genes. As with the Olson study, the relationship between genes and attitudes appears to be indirect; personality traits, which are highly heritable, seem to predispose people to certain political attitudes. But as the researchers point out, family members and peers can also mold political inclinations (Kandler, Bleidorn, & Riemann, 2012). It makes good sense if you think about it: If someone important to you takes a certain political stance, it might seem more appealing, or at least tolerable. The bottom line: Nurture may come out ahead in this particular case, but nature holds its own.

We have established that attitudes are shaped by experience and, to a lesser extent, heredity. This may be interesting from a theoretical standpoint, but what impact do these attitudes have on everyday life? Let’s explore how attitudes influence the choices we make.

Can Attitudes Predict Behavior?

There are many factors determining whether an attitude can predict a behavior (Ajzen, 2001). The strength of an attitude is important, with stronger, more enduring attitudes having a greater impact (Armitage & Christian, 2003; Holland, Verplanken, & Van Knippenberg, 2002). Specificity is also key; the more specific an attitude, the more likely it will sway behavior (Armitage & Christian, 2003). This principle is well illustrated by Davidson and Jaccard (1979), who examined the relationship between people’s general attitudes toward birth control and the use of birth control pills (the behavior). They found that general attitudes toward contraceptives were not as good at predicting their use as attitudes specific to birth control pills.

Not surprisingly, people are more likely to act on their attitudes when something important is at stake—like money. Imagine your college is holding a meeting to discuss the possibility of increasing student parking fees. What are the chances of your showing up to that meeting if you don’t own a car? The greater the personal investment you have in an issue, the more likely you are to act (Sivacek & Crano, 1982).

We now know that attitudes can influence behaviors, but is the opposite true—that is, can behaviors shape attitudes? Absolutely.

didn’t SEE that coming

Something Doesn’t Feel Right

Most people would agree that cheating on a girlfriend, boyfriend, or spouse is not right. Even so, some people contradict their beliefs by seeking sexual gratification outside their primary relationships. How do you think cheating makes a person feel—relaxed and at peace? Probably not. The tension that results when a behavior (in this case, cheating) clashes with an attitude (cheating is wrong) is known as cognitive dissonance (Aronson & Festinger, 1958; Festinger, 1957). One way to reduce cognitive dissonance is to adjust the behavior (stop fooling around). Another approach is to change the attitude to better match the behavior (cheating is actually good for our relationship, because it makes me a better partner). Such attitude shifts often occur without our awareness.

Most people would agree that cheating on a girlfriend, boyfriend, or spouse is not right. Even so, some people contradict their beliefs by seeking sexual gratification outside their primary relationships. How do you think cheating makes a person feel—relaxed and at peace? Probably not. The tension that results when a behavior (in this case, cheating) clashes with an attitude (cheating is wrong) is known as cognitive dissonance (Aronson & Festinger, 1958; Festinger, 1957). One way to reduce cognitive dissonance is to adjust the behavior (stop fooling around). Another approach is to change the attitude to better match the behavior (cheating is actually good for our relationship, because it makes me a better partner). Such attitude shifts often occur without our awareness.

The phenomenon of cognitive dissonance was elegantly brought to light in a study by Leon Festinger and J. Merrill Carlsmith (1959). Imagine, for a moment, that you are a participant in this classic study. The researchers have assigned you to a very boring task—placing 12 objects on a tray and then putting them back on the shelf, over and over again for a half-hour. Upon finishing, you spend an additional half-hour twisting 48 pegs ever so slightly, one peg at a time, again and again and again. How would you feel at the end of the hour—pretty bored, right?

Regardless of how you may feel about these activities, you have been paid money to convince someone else that they are a blast: “I had a lot of fun [doing] this task,” you say. “It was intriguing, it was exciting…” (Festinger & Carlsmith, 1959, p. 205). Unless you like performing repetitive behaviors like a robot, we assume you would feel some degree of cognitive dissonance, or tension resulting from this mismatch between your attitude (Ugh, this activity is so boring) and your behavior (saying, “I had so much fun!”). What could you do to reduce the cognitive dissonance? If you’re like participants in Festinger and Carlsmith’s study, you would probably adjust your attitude to better fit your claims. In other words, you would rate the task more interesting than it actually was.

But here’s the really interesting part: The students who were paid more money ($20 versus $1) were less inclined to change their attitudes to match their claim—a sign that they felt less cognitive dissonance. Apparently, the big bucks made it easier to justify their lies. I said I liked the boring task because I got paid $20, not because I actually liked it.

Here is one final example to drive home this concept of cognitive dissonance. We all know that smoking is bad for the body, but smokers around the world continue to light up. You would think awareness of health risks might lead to negative attitudes about smoking, as well as cognitive dissonance during the act (Smoking is dangerous; I am smoking, and this doesn’t feel right). Reducing the conflict between the attitude and behavior could be accomplished in one of two ways: by changing the attitude or by changing the behavior. Which path do smokers take?

APPARENTLY, BIG BUCKS MADE IT EASIER TO JUSTIFY THEIR LIES.

It appears that smokers often take a third route: thought suppression. They reduce cognitive dissonance by suppressing thoughts about the health implications of smoking. This helps explain why so many smokers don’t change their behavior when concerned friends and family members remind them of the dangers. So what should loved ones do to discourage the habit? One strategy is to reduce beliefs about positive outcomes, like pointing out that smoking is not effective as a social lubricant or relaxation aid (Kneer, Glock, & Rieger, 2012).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 12, we reported that many people smoke in response to stressors. To help people quit smoking, we must consider where they are in the process of smoking cessation (first time trying to quit, tried numerous times, etc.). Here, we see it’s important to consider cognitive dissonance as well.

We have now learned about cognitive processes that form the foundation of our social existence. Attributions help us make sense of events and behaviors, and attitudes provide continuity in the way we think and feel about the surrounding world. It’s time to shift our attention to behavior. How do people influence the way we act? Are you ready to meet running extraordinaire Julius Achon?

show what you know

Question 15.4

1. __________ are beliefs about the causes used to explain events, situations, and characteristics.

- Attributions

- Confederates

- Dispositions

- Attitudes

a. Attributions

Question 15.5

2. Because of the fundamental attribution error, we tend to be more likely to attribute causes of behaviors to the

- characteristics of the situation.

- factors involved in the event.

- length of the activity.

- disposition of the person.

d. disposition of the person.

Question 15.6

3. What three elements comprise an attitude?

Answers will vary, but may be based on the following information. Attitudes are the relatively stable thoughts, feelings, and responses one has toward people, situations, ideas, and things. Attitudes are composed of three elements: cognitive (beliefs or ideas), affective (mood or emotion), and behavioral (response).

Question 15.7

4. The just-world hypothesis is held by people who believe the world is a fair place; therefore, if someone is suffering, she must have done something to deserve it. What are some examples of the just-world hypothesis playing out in current popular stories or the media?

Answers will vary, but may be based on the following information. The just-world hypothesis is the tendency to believe the world is a fair place and individuals generally get what they deserve. For example, in the story of Cinderella, the doves that help Cinderella prepare for her wedding poke out the eyes of her evil stepsisters afterward.