11.1 An Introduction to Stress

DRIVE When Eric Flansburg first enrolled in the police academy at Onondaga Community College in upstate New York, there were 21 students in his class. Of those 21, only 6 graduated. Eric was not among them. Why? Because he failed one very important test: the Emergency Vehicle Operations Course (EVOC).

The EVOC requires exceptional driving skills. The test involves weaving a police car in and out of a zigzag maze of cones and making superfast lane changes—

Going into the test, Eric was well prepared. He had learned and rehearsed the steering and breaking techniques needed to succeed. But when the time came to put his hard-

Note: Quotations attributed to Eric Flansburg and Kehlen Kirby are personal communications.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

LO 1 Define stress and stressors.

LO 2 Describe the Social Readjustment Rating Scale in relation to life events and illness.

LO 3 Summarize how poverty, adjusting to a new culture, and daily hassles affect health.

LO 4 Identify the brain and body changes that characterize the fight-

LO 5 Outline the general adaptation syndrome (GAS).

LO 6 Describe the function of the hypothalamic–

LO 7 Explain how stressors relate to health problems.

LO 8 List some consequences of prolonged exposure to the stress hormone cortisol.

LO 9 Identify different types of conflicts.

LO 10 Illustrate how appraisal influences coping.

LO 11 Describe Type A and Type B personalities and explain how they relate to stress.

LO 12 Discuss several tools for reducing stress and maintaining health.

Stress and Stressors

LO 1 Define stress and stressors.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 9, we defined emotion as a psychological state that includes a subjective or inner experience. Emotion also has a physiological component and a behavioral expression. Here, we discuss stress responses, which are psychological, physiological, and emotional in nature.

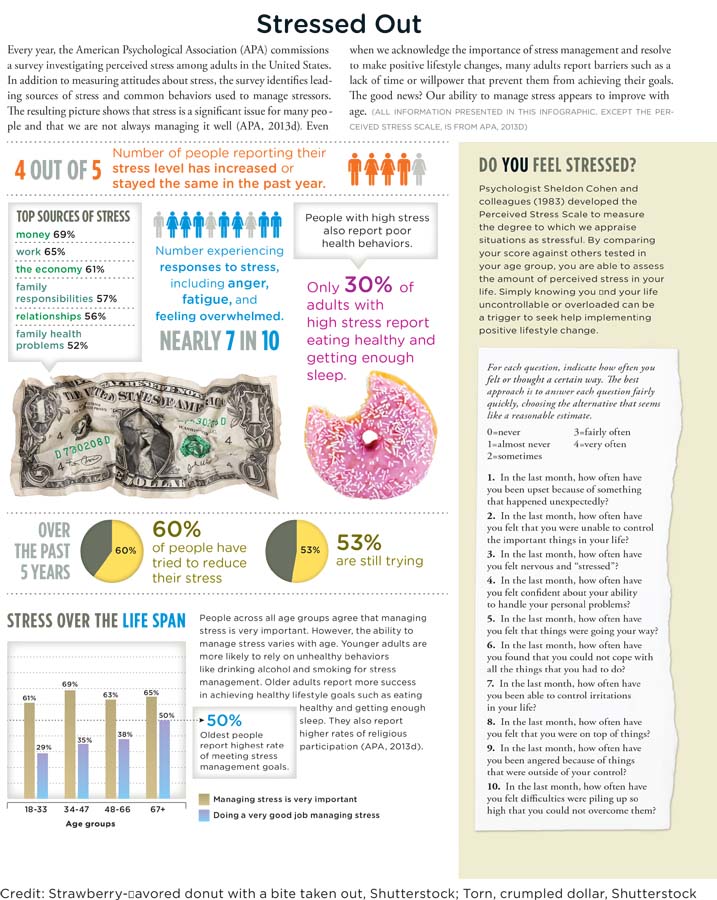

We all have an intuitive sense of what stress is, and many of us are more familiar with it than we would like. But what exactly is stress, where does it come from, and how does it affect our physical and mental health? Some people report they experience the feeling of stress, almost as if stress were an emotion. Others describe stress as if it were a force that needs to be resisted. An engineer might refer to stress as the application of a force on a target, such as the wing of an airplane, to determine how much load it can handle before breaking (Lazarus, 1993). Do you ever feel you might “break” because the load you bear causes such great strain (Infographic 11.1)?

INFOGRAPHIC 11.1

stress The response to perceived threats or challenges resulting from stimuli or events that cause strain.

stressors Stimuli that cause physiological, psychological, and emotional reactions.

Here, stress is defined as the response to perceived threats or challenges resulting from stimuli or events that cause strain, analogous to the airplane wing bending because of an applied load. For humans, these stimuli, or stressors, can cause psychological, physiological, and emotional reactions. As you read this chapter, be careful not to confuse how we react to stressors with the stressors themselves; stress is the response and stressors are the cause (Harrington, 2013). Hans Selye (sěl’yě; 1907–

There are countless types of stressors. They can be events, such as police academy driving tests, or beliefs and attitudes, like Eric’s thoughts and worries about not passing the test. Stressors can even be people, like the drill instructors who run the police academy’s Saturday morning physical training. Starting at 6:00 A.M., these guys lead Onondaga’s aspiring police officers through 3 hours of running, push-

Police cadets practice arrest procedures at an academy in Gurabo, Puerto Rico. Drill instructors go to great lengths to prepare aspiring officers for the extreme physical and mental stressors they will face on their beats.

What are the stressors in your life? Some exist outside of you, like homework assignments, dirty dishes in the sink, and job demands. Others are more internal, like the anxiety stemming from a strained relationship or the pressure of wishing to excel. Generally, we experience stress in response to stressors, although there is at least one exception to this rule: People with anxiety disorders can feel intense anxiety in the absence of any apparent stressors (Chapter 12). Which brings us to another point: Stress is very much related to how one perceives the surrounding world.

In many cases, stress results from a perceived threat, because what constitutes a threat differs from one person to the next. The police academy driving test might have been threatening to Eric because he felt anxious about failing, while another student viewed the test as an opportunity to shine. Similarly, Eric may have felt completely relaxed taking written exams that other students found highly threatening.

Remember that stress can have psychological, physiological, and emotional effects. Eric’s physiological reaction to the driving test may have included increased blood pressure and heart rate, but he was far more aware of the psychological and emotional components of his stress response. Bursting through the starting gates, his mind raced from one thought to the next. He was envisioning every little thing he needed to do to pass the exam and at the same time saying to himself, Eric, Eric, you can’t fail.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 10, we presented self-

The very same day that Eric failed his driving test, he resolved to return to the academy and start the program again. This minor setback was not going to interfere with his childhood dream of becoming a police officer, and there was no way it was going to define his experience at the academy. “When you fall down, you have to get back up,” Eric says. “That’s the only way to move forward in life.”

Not all people would have responded this way; plenty would have viewed the test as the end of their journey. (I guess I was never meant to be a police officer.) As you will learn in this chapter, the ways people experience and cope with stressors are highly variable. The strategies used and the beliefs about one’s ability to cope have a profound impact on reactions to stress.

EVERYTHING HAPPENS FOR A REASON In three decades of life, Eric has experienced his fair share of stressors. Immediately after graduating from high school in upstate New York, he traveled to an Air Force base in San Antonio, Texas, to begin basic training, a stepping-

EVERYTHING HAPPENS FOR A REASON In three decades of life, Eric has experienced his fair share of stressors. Immediately after graduating from high school in upstate New York, he traveled to an Air Force base in San Antonio, Texas, to begin basic training, a stepping-

After about a year of arduous training in the Air Force, Eric suffered a disabling injury and had to be discharged. It was a huge letdown, but Eric believes everything happens for a reason. He returned to New York and got a job at a dairy plant where he moved up the company ranks to become a high-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 9, we introduced arousal theory, which suggests behaviors can arise out of the need for stimulation or arousal. Here, we point out that some people seek stressors in order to maintain a satisfying level of arousal.

A dairy plant employee toils among steel vats of milk. Keeping the storage vessels and equipment sterile is an enormous responsibility; if the product becomes contaminated, thousands of consumers might be sickened. As Eric can testify, working as a sanitation manager can cause significant day-

When you ask Eric how the various stressors in his life affected him, he has few negative things to say. Even while working upwards of 70 hours a week at the plant, he was eating well, sleeping soundly, and maintaining balance in his life. Despite the long hours and constant pressure, he felt relatively happy and fulfilled. Have you ever considered that some stressors can be positive? According to arousal theory, humans seek an optimal level of arousal, and what is optimal is not the same for everyone.

eustress (yōōˈ-stres) The stress response to agreeable or positive stressors.

distress The stress response to unpleasant and undesirable stressors.

EUSTRESS AND DISTRESS Clearly, stressors cannot be avoided completely. And some stressors are enjoyable: we feel excitement before a big trip or the birth of a new baby. For Eric, getting married and witnessing the birth of his first child were among the most stressful and joyful events in life. “Oh man, you want to talk about sweaty palms, me shaking, and a whole lot of emotion?” he says, remembering the day he stood at the altar. And the birth of his son? “Unreal,” he says. Immediately after the delivery, doctors placed his son on his wife’s chest. The baby’s eyes were still closed, but when he opened them, Eric was the first person he saw. It was the proudest moment of Eric’s life. This “good” kind of stressor leads to eustress (yōōˈ-stres), which is the stress response to agreeable or positive events. Of course, most people associate stress with negative events. These types of undesirable or disagreeable occurrences lead to the particular stress response known as distress. Now let’s find out how eustress and distress might affect your health.

Major Life Events

LO 2 Describe the Social Readjustment Rating Scale in relation to life events and illness.

Holmes and Rahe (1967) were among the first to propose that life-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we explained that a positive correlation indicates that as one variable increases, so does the other variable. Here, we see a positive correlation between life events and health problems: The more life events people have experienced, the more health problems they are likely to have.

SOCIAL READJUSTMENT RATING SCALE Illnesses can be clearly defined and identified, but how do psychologists measure life events? Holmes and Rahe (1967) developed the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) to do just that. With the SRRS, participants are asked to read through a list of events and experiences, and determine which of these happened during the previous year and how many times they occurred. A score is then calculated based on severity ratings of events and the frequency of their occurrence. An event like the death of a spouse has a greater severity rating than something like a traffic violation. Participants are also asked to report any illnesses or accidents they experienced during the same period. Researchers then use this information to look at the correlation between life events and health problems (Kobasa, 1979). Correlations range between .20 and .78, although they are generally lower than .30 (Rabkin & Struening, 1976). But remember, a correlation between life events and illness (or any correlation for that matter) is no proof of causality. There is always the possibility that a third factor, such as poverty, may be causing both illnesses and major life-

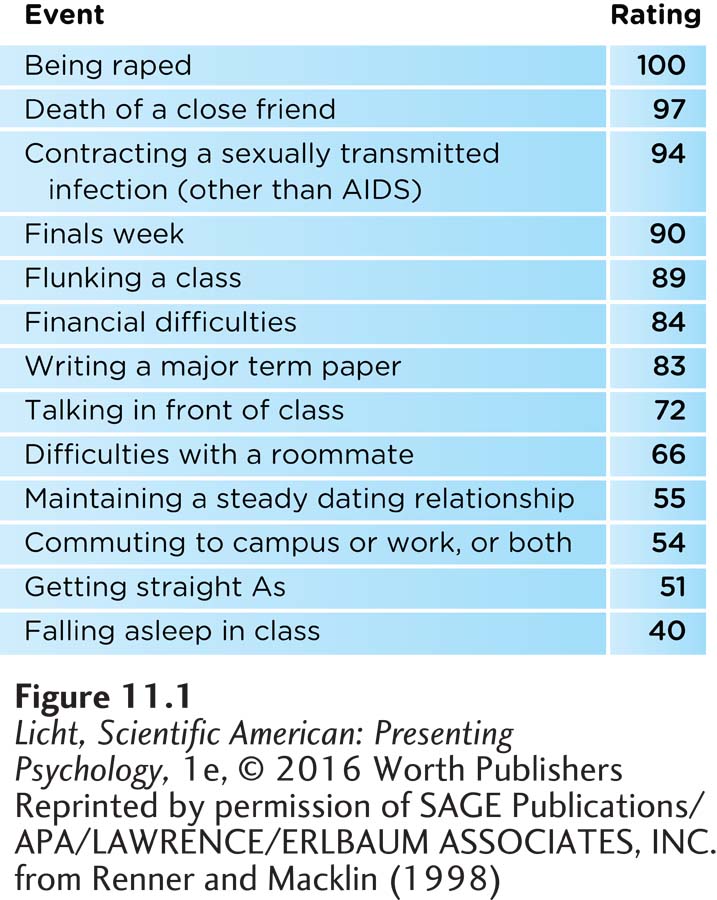

First used in the late 1960s, the SRRS has been updated over the years. (For example, the original scale included “mortgage over $10,000” as an event.) The rating scale has also been adapted to better match the life events of specific populations; an example is the College Undergraduate Stress Scale (CUSS; Renner & Mackin, 1998; Figure 11.1). Even with this degree of specificity, the scale may not be suitable for every person. In addition to dealing with term papers, midterms, and other college-

Imagine you were tasked with redesigning the College Undergraduate Stress Scale (CUSS) to bring it up to date. How would you decide what types of items to include in your rating scale? You could begin as many researchers do—

try this

Another possible problem with self-

Looking across cultures, we see most people rate the weight of life-

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Physician assistant Klubo Mulba (left) smiles at her former client, Surprise Otto, at JFK Hospital in Monrovia, Liberia. One of Liberia’s first mental health clinicians, Mulba received her training through a joint program between The Carter Center and the Liberia Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. On top of dealing with the aftermath of an Ebola epidemic, Liberia’s population continues to recover from a 13-

One type of event not included in the SRRS, but which is familiar to police officers and other first responders, is a major disaster experience. These cataclysmic events include natural disasters such as hurricanes, earthquakes, and tornadoes, as well as multicar accidents, war, and terrorist attacks. The emotional and physical responses to such occurrences can last for many years, manifesting themselves in nightmares, flashbacks, depression, grief, anxiety, and other symptoms related to posttraumatic stress disorder.

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) A psychological disorder characterized by exposure to or being threatened by an event involving death, serious injury, or sexual violence; can include disturbing memories, nightmares, flashbacks, and other distressing symptoms.

In order to be diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a person must be exposed to or threatened by an event involving death, serious injury, or some form of sexual violence. Someone could develop PTSD after witnessing a violent assault or accident, or upon learning about the traumatic experiences of family members, close friends, perhaps even strangers. In some cases, the exposure to trauma is ongoing. First responders like Eric, for example, may witness disturbing scenarios on a weekly basis. For veterans and service members previously deployed to war zones in Afghanistan and Iraq, the estimated incidence of PTSD is 13.8%, based on a study of almost 2,000 participants questioned about their symptoms (Schell & Marshall, 2008). In contrast, around 3.5% of the general population is estimated to have received a PTSD diagnosis during the previous 12 months (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

However, not everyone exposed to trauma will develop PTSD. Over the course of a lifetime, most people will experience an event that qualifies as a “psychological trauma,” but only 5–

Many people with PTSD try to avoid environmental cues (people, places, or objects) linked to the trauma. If someone were involved in a serious car accident on U.S. Highway 101, then simply driving along that thoroughfare may trigger unwanted memories. Other symptoms include difficulty remembering the details of the event, unrealistic self-

Among those at risk for PTSD are police officers (Berger et al., 2011), many of whom bear witness to bloody crime scenes, traumatized victims, and gun violence. But it is not just these types of traumas that impact police officers; just as important are the more chronic stressors, like being overworked, having unpleasant relationships with colleagues, and not getting enough time with family (Collins & Gibbs, 2003; Maguen et al., 2009).

It’s Nonstop: Chronic Stressors

You don’t have to be a police officer to appreciate the burden of everyday stress. For some of us, stressors come from balancing school and work, or taking care of young children. Many face the constant stressor of battling a chronic illness like diabetes, asthma, or cancer (Sansom-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 9, we described various sexually transmitted infections (STIs), diseases that are passed on through sexual activity. There are many types of STIs, but most are caused by viruses or bacteria. Viral STIs such as HIV and herpes do not have cures, only treatments to reduce symptoms.

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) A virus transferred via bodily fluids (blood, semen, vaginal secretions, or breast milk) that causes the breakdown of the immune system, eventually resulting in AIDS.

acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) This condition, caused by HIV, generally results in a severely compromised immune system, which makes the body vulnerable to other infections.

HIV AND AIDS One of the most feared sexually transmitted infections (STIs), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is spread through the transfer of bodily fluids (such as blood, semen, vaginal fluid, or breast milk). Often the virus does not show up on blood tests for up to 6 months after infection, so you cannot assume you are “safe” just because you receive a negative test result—

HIV has taken an enormous toll on human life. Since the virus was first identified in 1981, it has infected nearly 78 million people, about half of whom have died (WHO, 2015). Worldwide, HIV is a leading cause of death, and in sub-

What comes to mind when you think of stressors associated with HIV? Perhaps you imagine receiving the diagnosis, sharing the news with loved ones, or facing the possibility of developing AIDS. Did you think about the cost of treatment? HIV medications are very expensive, approximately $20,000 per year per person in the United States. And because of funding shortfalls, some 2000 Americans may not be getting the therapies they need (Maxmen, 2012). The problem is global. In 2010, 7.6 million HIV sufferers around the world could not gain access to treatment (Granich et al., 2012). This inability to pay for proper medical treatment relates to a stressor that is even more widespread than HIV: poverty.

LO 3 Summarize how poverty, adjusting to a new culture, and daily hassles affect health.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 7, we discussed the relationship between poverty and cognitive abilities (socioeconomic status is associated with scores on intelligence tests). In Chapter 8, we presented evidence suggesting that isolation and lack of stimulation can hamper the development of young brains. Here, we highlight the link between poverty-

POVERTY The number of Americans living at or below the poverty line is significant. As of 2011, 22% of children under 6 years in the United States were living below the poverty level (Addy, Engelhardt, & Skinner, 2013). People struggling to make ends meet experience numerous stressors, including poor health care, lack of preventive health care, noisy living situations, overcrowding, violence, and underfunded schools (Blair & Raver, 2012; Mistry & Wadsworth, 2011). The cycle of poverty is difficult to break, so these stressors often persist across generations. The longer people live in poverty, the more exposure they have to stressors, and the greater the likelihood they will become ill (Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011). For children in particular, the impact of socioeconomic status (SES) can have lifelong repercussions because environmental stressors affect the developing brain. Some of the factors associated with low SES and permanent changes to the brain include poor nutrition, toxins in the environment, and abuse. In some cases, these irregularities in brain development may lead to differences in “adult neurocognitive outcomes” (D’Angiulli, Lipina, & Olesinska, 2012, September 6). Factors linked to poverty have been associated with “inequalities” in the development of cognitive and socioemotional abilities, which can impact performance in school and at work (Lipina & Posner, 2012, August 17).

acculturative stress (ə⌍kəl-

A woman shops for groceries in the Chinatown area of Flushing in Queens, New York. Queens is the most ethnically varied urban community on the planet, providing a home for people from more than 100 countries (Weber, 2013, April 30). Immigrants can either assimilate into, separate from, or integrate into their new cultures.

ACCULTURATIVE STRESS Another increasingly common source of stress is migration. As of 2013, there were 232 million migrants dispersed across the world (United Nations Population Fund, n.d., para. 1). These people may deal with varying degrees of acculturative stress (ə⌍kəl-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 8, we discussed Piaget’s concept of assimilation, which refers to a cognitive approach to dealing with new information. This suggests that a person attempts to understand new information using her existing knowledge base. Here, assimilation means letting go of old ways and adopting the customs of a new culture.

There are various ways people respond to acculturative stress (Berry, 1997). Some try to assimilate, letting go of old ways and adopting those of the new culture. But assimilation can cause problems if family members or friends from the old culture reject the new one, or have trouble assimilating themselves. Another approach is to cling to one’s roots and remain separated from the new culture. This can be very problematic if the new culture does not support this type of separation and requires assimilation. A combination of these two approaches is integration, or holding on to some elements of the old culture, but also adopting aspects of the new one.

The degree of acculturative stress varies greatly from one individual to the next. Some people thrive on new soil (a prime example being Mohamed Dirie from Chapter 9), while others struggle with the stress of starting over. What determines the intensity of acculturative stress, and why do some people seem to have an easier time with it than others?

across the WORLD

The Stress of Starting Anew

Imagine trying to get a job, pay your bills, or simply make friends in a world where most everyone speaks a foreign language. Familiarity with language appears to play a key role in determining acculturative stress levels. A study of Haitian immigrants in the United States found lower levels of acculturative stress among those who spoke English (Belizaire & Fuertes, 2011). “The ability to speak English is crucial to the adjustment and well-

Imagine trying to get a job, pay your bills, or simply make friends in a world where most everyone speaks a foreign language. Familiarity with language appears to play a key role in determining acculturative stress levels. A study of Haitian immigrants in the United States found lower levels of acculturative stress among those who spoke English (Belizaire & Fuertes, 2011). “The ability to speak English is crucial to the adjustment and well-

social support The assistance we acquire from others.

IMMIGRATION IS STRESSFUL, ESPECIALLY IF YOU DON’T SPEAK THE NEW LANGUAGE.

Fortunately, there are ways to combat acculturative stress. One of the best defenses is social support, or assistance from others. A small study of refugees in Austria indicated that those who had social support from a sponsor experienced less anxiety and depression and had an easier time adapting (Renner, Laireiter, & Maier, 2012).

Kehlen Kirby has one of the most stressful jobs imaginable—

The stresses of acculturation tend to be gnawing and constant, but some stressors are sudden and dramatic. These are the types that ambulance drivers and paramedics encounter every day. Welcome to the world of Kehlen Kirby.

THE PARAMEDIC’S ROLLERCOASTER Kehlen Kirby sees more pain and suffering in one month than most people do in a lifetime. In his 8 years working as an emergency medical services (EMS) provider in Pueblo, Colorado, this 26-

THE PARAMEDIC’S ROLLERCOASTER Kehlen Kirby sees more pain and suffering in one month than most people do in a lifetime. In his 8 years working as an emergency medical services (EMS) provider in Pueblo, Colorado, this 26-

Being involved in life-

What a Hassle, What a Joy

daily hassles Minor and regularly occurring problems that can act as stressors.

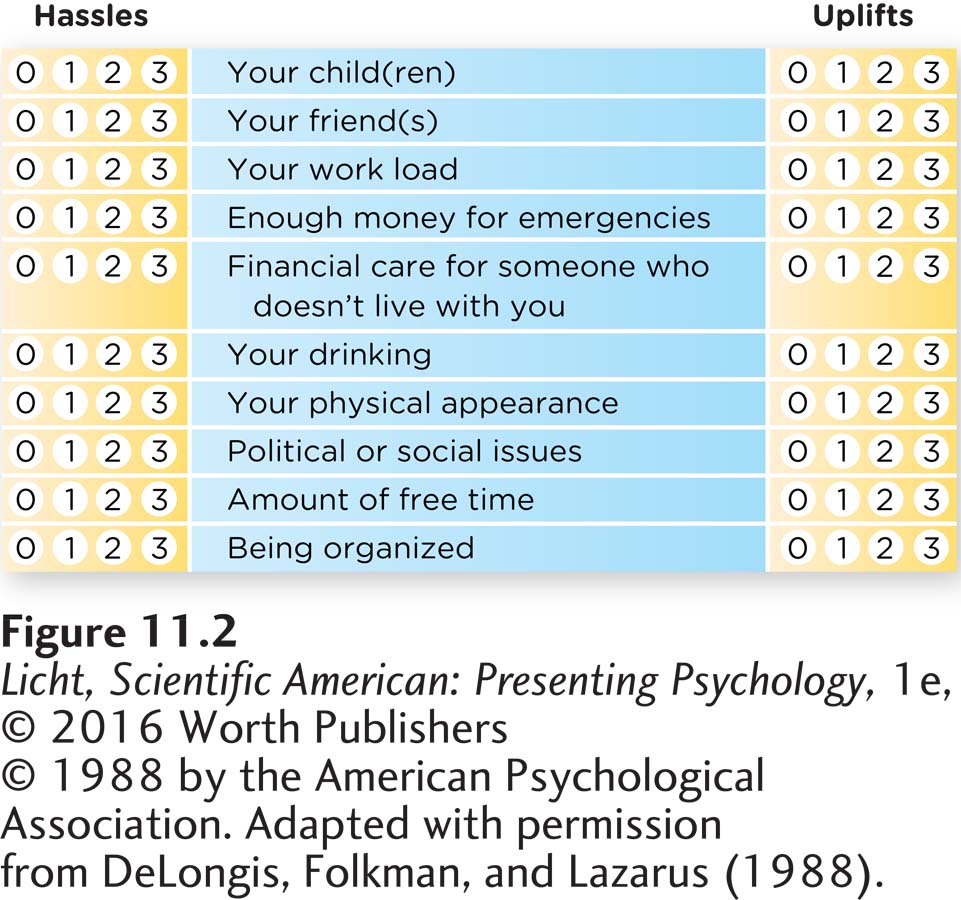

Research participants were instructed to circle a number rating the degree to which each item was a hassle (left column) and an uplift (right column). Numbers range from 0 (“none or not applicable”) to 3 (“a great deal”). The scale includes 53 items, a sample of which are shown here.

Daily hassles are the minor problems or irritants we deal with on a regular basis, such as traffic, financial worries, misplaced keys, messy roommates—

uplifts Experiences that are positive and have the potential to make one happy.

Uplifts are positive experiences that have the potential to make us happy. Think about the last time you smiled; it was likely in response to an uplift, such as a funny text from a friend, a child presenting you with a handmade gift, or a congratulatory e-

DeLongis and colleagues (1988) developed a scale of daily hassles and uplifts, and used it to explore the relationship between stress and illness (Figure 11.2). They asked participants to read through a list of 53 items that could be either hassles or uplifts, such as meeting deadlines, maintaining a car, interacting with fellow workers, and dealing with the weather. Participants then rated these items on a 4-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 9, we discussed different ways that we can increase our well-

How do hassles and uplifts affect psychological and social health? One group of researchers studied two Israeli populations (Jewish and Arab), exploring the similarities and differences within subgroups living in the same country. While differences existed, the researchers noted some important similarities. In both groups, for example, daily uplifts had a positive impact on “family satisfaction” and daily hassles had a negative impact on “life satisfaction,” though the meaning of “uplift” differed between the two groups (Lavee & Ben-

Now that we have explored various types of stressors, from major life events to everyday annoyances, let’s find out what occurs in the body and brain when we respond.

show what you know

Question 1

1. ____________ is a response to perceived threats or challenges resulting from stimuli that cause strain.

Stress

Question 2

2. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale was created to measure the severity and frequency of life events. This scale is most often used to examine the relationship between stressors and which of the following?

aging

levels of eustress

perceived threats

illness

d. illness

Question 3

3. ____________ can occur when a person must adjust to life in a new country, often due to unfamiliar language, religious beliefs, and holidays.

Eustress

Acculturative stress

Uplifts

Posttraumatic stress disorder

b. Acculturative stress

Question 4

4. Reflect upon the last few days. Can you think of three uplifts and three hassles you have experienced during this period?

Answers will vary, but can be based on the following definitions. Daily hassles are the minor problems or irritants we deal with on a regular basis (for example, heavy traffic, financial worries, messy roommates). Uplifts are positive experiences that have the potential to make us happy (for example, a humorous text message, a small gift).