12.2 Worried Sick: Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders

UNWELCOME THOUGHTS: MELISSA’S STORY Melissa Hopely was about 5 years old when she began doing “weird things” to combat anxiety: flipping light switches on and off, touching the corners of tables, and running to the kitchen to make sure the oven was turned off. Taken at face value, these behaviors may not seem too strange, but for Melissa they were the first signs of a psychological disorder that eventually pushed her to the edge.

UNWELCOME THOUGHTS: MELISSA’S STORY Melissa Hopely was about 5 years old when she began doing “weird things” to combat anxiety: flipping light switches on and off, touching the corners of tables, and running to the kitchen to make sure the oven was turned off. Taken at face value, these behaviors may not seem too strange, but for Melissa they were the first signs of a psychological disorder that eventually pushed her to the edge.

Anxiety is a normal part of growing up. Children get nervous for an untold number of reasons: doctors’ appointments, the first day of school, or the neighbor’s German shepherd. But Melissa was not suffering from common childhood jitters. Her anxiety overpowered her physically, gripping her arms and legs in pain and twisting her stomach into a knot. It affected her emotionally, bringing on a vague feeling that something awful was about to occur—

As Melissa grew older, her behaviors became increasingly regimented. She felt compelled to do everything an even number of times. Instead of entering a room once, she would enter or leave twice, four times, perhaps even 20 times—

Melissa Hopely was about 3 years old when the photo on the left was taken. Within a couple of years, she would begin to experience the symptoms of a serious mental disorder that would carry into adulthood.

What was she so afraid of? Dying, losing all her friends, and growing up to be jobless, homeless, and living in a dumpster. She also feared striking out in her next softball game and making the whole team lose. Something dreadful was about to happen, though she couldn’t quite put her finger on what it was. In reality Melissa had little reason to worry. She had health, smarts, beauty, and a loving circle of friends and family.

We all experience irrational worries from time to time, but Melissa’s anxiety had become overwhelming. Where does one draw the line between anxiety that is normal and anxiety that is abnormal?

LO 4 Define anxiety disorders and demonstrate an understanding of their causes.

anxiety disorders A group of psychological disorders associated with extreme anxiety and/or debilitating, irrational fears.

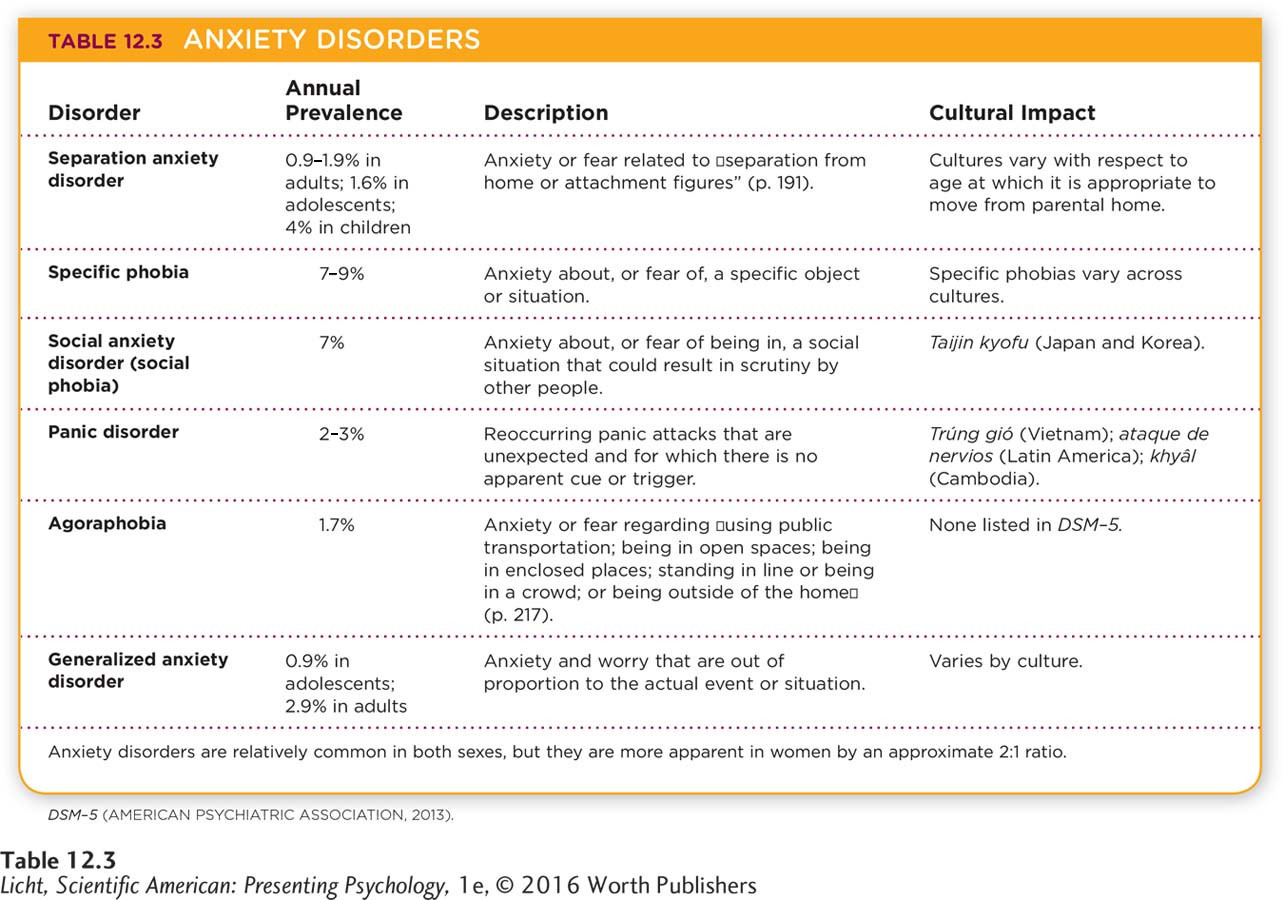

Think about the objects or situations that cause you to feel afraid or uneasy. Maybe you fear creepy crawly insects, slithery snakes, or crowded public spaces. A mild fear of spiders or overcrowded subways is normal, but if you become highly disturbed by the mere thought of them, or if the fear interferes with your everyday functioning, then a problem may exist. People who suffer from anxiety disorders have extreme anxiety and/or irrational fears that are debilitating (Table 12.3).

How do we differentiate between normal anxiety and an anxiety disorder? We look at the degree of dysfunction the anxiety causes, how much distress it creates, and whether it gets in the way of everyday behavior (interfering with relationships, work, and time management, for example). Let’s take a look at some of the anxiety disorders identified in the DSM–

Panic Disorder

panic attack Sudden, extreme fear or discomfort that escalates quickly, often with no obvious trigger, and includes symptoms such as increased heart rate, sweating, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, lightheadedness, and fear of dying.

panic disorder A psychological disorder that includes recurrent, unexpected panic attacks and fear that can cause significant changes in behavior.

Actress Emma Stone, known for her roles in movies such as The Help and The Amazing Spider-

What should you do if you see somebody trembling and sweating, gasping for breath, or complaining of heart palpitations? If you are concerned it’s a heart attack, you may be correct; call 911 immediately if you are not sure. However, a person experiencing a panic attack may behave very similarly to someone having a heart attack. A panic attack is a sudden, extreme fear or discomfort that escalates quickly, often with no evident cause, and includes symptoms such as increased heart rate, sweating, shortness of breath, chest pain, nausea, lightheadedness, and fear of dying. A diagnosis of panic disorder requires such attacks to recur unexpectedly and have no obvious trigger. In addition, the person worries about having more panic attacks, or she feels she may be losing control. People with panic disorder often make decisions that are maladaptive, like purposefully avoiding exercise or places that are unfamiliar.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we described how the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system directs the body’s stress response. When a stressful situation arises, the sympathetic nervous system prepares the body to react, causing the heart to beat faster, respiration to increase, and the pupils to dilate, among other things.

THE BIOLOGY OF PANIC DISORDER Panic disorder does appear to have a biological cause (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Researchers have identified specific parts of the brain thought to be responsible for panic attacks, including regions of the hypothalamus, which is involved in the fight-

GENETICS, GENDER, AND PANIC DISORDER Panic disorder affects about 2–

Women are twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with panic disorder, and this disparity is already apparent by the age of 14 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Craske et al., 2010; Weber et al., 2012). Such gender differences may have a biological basis, but we must also consider psychological and social factors.

In Chapter 5, we described how, for Little Albert, an originally neutral stimulus (a rat) was paired with an unconditioned stimulus (a loud sound), which led to an unconditioned response (fear). With repeated pairings, the conditioned stimulus (the rat) led to a conditioned response (fear).

LEARNING AND PANIC DISORDER Some researchers propose that learning—

COGNITION AND PANIC DISORDER Other researchers suggest there is a cognitive component of panic disorder, with some individuals misinterpreting physical sensations as signs of major physical or psychological problems (Clark et al., 1997; Teachman, Marker, & Clerkin, 2010). For example, many people have a strange sensation when their hearts skip a beat (technically known as arrhythmia), but they realize it is probably not serious, perhaps just the result of too much coffee. A person with panic disorder might interpret that sensation as an indication of an imminent heart attack.

Specific Phobias and Agoraphobia

specific phobia A psychological disorder that includes a distinct fear or anxiety in relation to an object or situation.

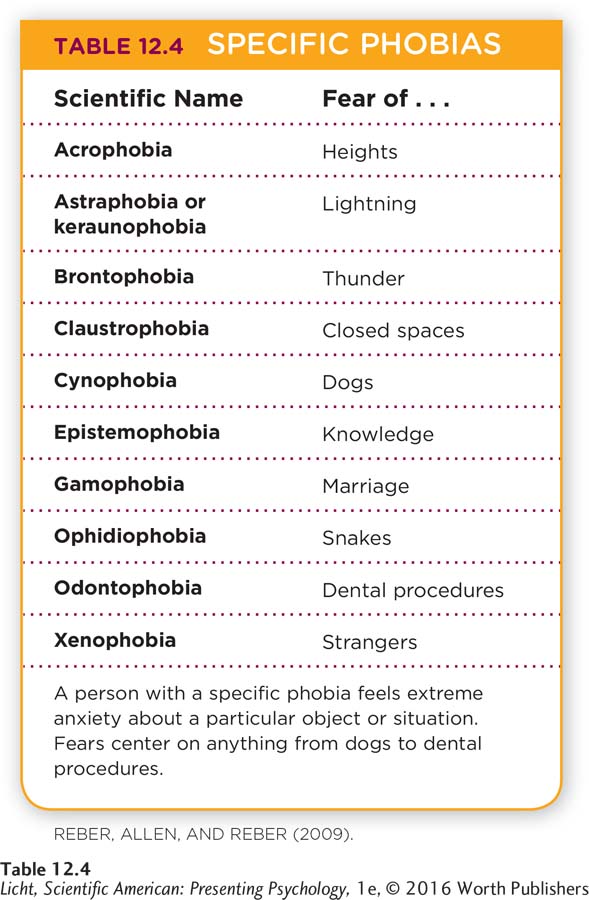

Panic attacks can occur without apparent triggers. This is not the case with a specific phobia, which centers on a particular object or situation, such as rats or airplane travel. Most people who have a phobia do their best to avoid the feared object or situation. If avoidance is not possible, they withstand it, but only with extreme fear and anxiousness. Take a look at Table 12.4 for a list of some specific phobias.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we discussed negative reinforcement; behaviors increase when they are followed by the removal of something unpleasant. Here, the avoidance behavior takes away the anxious feeling, increasing the likelihood of avoiding the object in the future.

Emotional responses, such as fear of spiders, snakes, and heights, may have evolved to protect us from danger (Plomin, DeFries, Knopik, & Neiderhiser, 2013). Avoiding harmful creatures and precarious drop-

LEARNING AND SPECIFIC PHOBIAS As with panic disorder, phobias can be explained using the principles of learning (LeBeau et al., 2010). Classical conditioning may lead to the acquisition of a fear, through the pairing of stimuli. Operant conditioning could maintain the phobia, through negative reinforcement; if anxiety (the unpleasant stimulus) is reduced by avoiding a feared object or situation, the avoidance behavior is negatively reinforced and thus more likely to recur. Observational learning can also help explain the development of a phobia. Simply watching someone else experience a phobia could create fear in an observer. Some research demonstrates that even rhesus monkeys become afraid of snakes if they observe other monkeys reacting fearfully to real or toy snakes (Heyes, 2012; Mineka, Davidson, Cook, & Keir, 1984).

BIOLOGY, CULTURE, AND SPECIFIC PHOBIAS Phobias can also be understood through the lens of evolutionary psychology. Humans seem to be biologically predisposed to fear certain threats such as spiders, snakes, foul smells, and bitter foods. Spiders, in particular, may inspire fear or disgust because they can be dangerous, but such reactions can also be influenced by culture (Gerdes, Uhl, & Alpers, 2009). From an evolutionary standpoint, these types of fears would tend to protect us from true danger. But the link between anxiety and evolution is not always so apparent. It’s hard to imagine how an intense fear of being in public, for example, would promote survival.

agoraphobia (a-

AGORAPHOBIA Do you ever feel a little anxious when you are out in public, in a new city, or at a crowded amusement park? A person with agoraphobia (a-

Social Anxiety Disorder

In Puerto Rico and other parts of Latin America, stress may trigger a syndrome known as ataque de nervios, or “attack of the nerves.” People suffering from this condition may burst into tears, yell frantically, behave aggressively, and feel a sensation of heat moving from the chest to the head (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

According to the DSM–

across the WORLD

The Many Faces of Social Anxiety

Every society has its own collection of social norms, so it’s not surprising that social anxiety presents itself in distinct ways across the world. People in Asian cultures, for example, are more likely to avoid outward displays of anxiety, such as blushing, sweating, or shaking. Some individuals in Japan and Korea suffer from taijin kyofu, a cultural syndrome characterized by an intense fear of offending or embarrassing other people with one’s body odor, stomach rumblings, or facial expressions. Note that with taijin kyofu, the fear is associated with causing distress in others. In the United States and other Western countries, social anxiety is more centered on humiliating oneself (Hofmann, Asnaani, & Hinton, 2010; Kinoshita et al., 2008). This distinction may stem from cultural differences; Japanese and Korean societies are more collectivist than those of the West (Rapee & Spence, 2004). Collectivist cultures value social harmony over individual needs, so causing discomfort in others is worse than personal humiliation.

Every society has its own collection of social norms, so it’s not surprising that social anxiety presents itself in distinct ways across the world. People in Asian cultures, for example, are more likely to avoid outward displays of anxiety, such as blushing, sweating, or shaking. Some individuals in Japan and Korea suffer from taijin kyofu, a cultural syndrome characterized by an intense fear of offending or embarrassing other people with one’s body odor, stomach rumblings, or facial expressions. Note that with taijin kyofu, the fear is associated with causing distress in others. In the United States and other Western countries, social anxiety is more centered on humiliating oneself (Hofmann, Asnaani, & Hinton, 2010; Kinoshita et al., 2008). This distinction may stem from cultural differences; Japanese and Korean societies are more collectivist than those of the West (Rapee & Spence, 2004). Collectivist cultures value social harmony over individual needs, so causing discomfort in others is worse than personal humiliation.

BODY ODOR AND OTHER CULTURAL AFFRONTS

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Synonyms

taijin kyofu taijin kyofusho

Thus far we have discussed anxiety disorders that center on specific objects or scenarios, but what about anxiety that is pervasive, or widespread? Someone with generalized anxiety disorder experiences an excessive amount of worry and anxiety about many activities relating to family, health, school, and other aspects of daily life (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The psychological distress is accompanied by physical symptoms such as muscle tension and restlessness. Individuals with generalized anxiety disorder may avoid activities they believe will not go smoothly, spend a great deal of time getting ready for such events, or wait until the very last minute to engage in the anxiety-

generalized anxiety disorder A psychological disorder characterized by an excessive amount of worry and anxiety about activities relating to family, health, school, and other aspects of daily life.

Twin studies suggest there is a hereditary component to generalized anxiety disorder. This genetic factor appears to be associated with irregularities in parts of the brain associated with fear, such as the amygdala and hippocampus (Hettema et al., 2012; Hettema, Neale, & Kendler, 2001). Environmental factors such as adversity in childhood and overprotective parents also appear to be associated with the development of generalized anxiety disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

MELISSA’S STRUGGLE We introduced this section with the story of Melissa Hopely. Melissa struggled with anxiety and felt compelled to perform elaborate rituals in order to assuage it. Her behavior caused significant distress and dysfunction, which suggests that it was abnormal, but does it match any of the anxiety disorders described above? Her anxiety was not attached to a specific object or situation, so it doesn’t appear to fit the description of a phobia. Nor was her anxiety nonspecific, as might be the case with generalized anxiety disorder. Melissa’s fears emanated from nagging, dreadful thoughts generated by her own mind. She may not have been struggling with an anxiety disorder per se, but she certainly was experiencing anxiety as a result of some disorder. So what was it?

MELISSA’S STRUGGLE We introduced this section with the story of Melissa Hopely. Melissa struggled with anxiety and felt compelled to perform elaborate rituals in order to assuage it. Her behavior caused significant distress and dysfunction, which suggests that it was abnormal, but does it match any of the anxiety disorders described above? Her anxiety was not attached to a specific object or situation, so it doesn’t appear to fit the description of a phobia. Nor was her anxiety nonspecific, as might be the case with generalized anxiety disorder. Melissa’s fears emanated from nagging, dreadful thoughts generated by her own mind. She may not have been struggling with an anxiety disorder per se, but she certainly was experiencing anxiety as a result of some disorder. So what was it?

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

LO 5 Summarize the symptoms and causes of obsessive-

obsessive-

obsession A thought, an urge, or an image that happens repeatedly, is intrusive and unwelcome, and often causes anxiety and distress.

compulsion A behavior or “mental act” that a person repeats over and over in an effort to reduce anxiety.

At age 12, Melissa was diagnosed with obsessive-

The Pepsi cans in David Beckham’s refrigerator are arranged in a perfect line or in groups of two; if the total number of cans is odd, he removes one to make it even. When Beckham goes to a hotel, he can only relax after systematically organizing all the objects in his room. The British soccer legend reportedly suffers from obsessive-

Those who suffer from OCD experience various types of obsessions and compulsions. In many cases, obsessions focus on fears of contamination with germs or dirt, and compulsions revolve around cleaning and sterilizing (Cisler, Brady, Olatunji, & Lohr, 2010). One such OCD sufferer reported washing her hands until her knuckles bled, living in fear that she would kill someone with her germs (Turk, Marks, & Horder, 1990). Other common compulsions include repetitive rituals and checking behaviors. Melissa, for example, developed a compulsion about locking her car. Unlike most people, who lock their cars once and walk away, Melissa felt compelled to lock it twice. Then she would begin to wonder whether the car was really locked, so she would lock it a third time—

CONNECTIONS

Negative reinforcement (Chapter 5) promotes the maladaptive behavior here. The compulsions are not actually preventing unwanted occurrences, but they do lead to a decrease in anxiety, and thus negatively reinforce the behavior. Repeatedly locking the car temporarily reduced Melissa’s anxiety, making her more likely to perform this behavior in the future.

THE OCD DIAGNOSIS How do you explain this type of behavior? OCD compulsions often aim to thwart unwanted situations, and thereby reduce anxiety and distress. Melissa was tormented by multiple obsessions ranging from catastrophic (the death of her mother) to minor (someone stealing her iPod). But the compulsive behaviors of OCD are either “clearly excessive” or not logically related to the event or situation the person is trying to prevent (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Where do we draw the line between obsessive or compulsive behavior and the diagnosis of a disorder? Remember, behaviors or symptoms must be significantly distressing or disabling in order to be considered abnormal and qualify as a disorder. This is certainly the case with OCD, in which obsessions and/or compulsions are very time-

THE BIOLOGY OF OCD Evidence suggests that the symptoms of OCD are related to abnormal activity of neurotransmitters. Reduced activity of serotonin is thought to play a role, though other neurotransmitters are also being studied (Bloch, McGuire, Landeros-

Why do these biological differences arise? There appears to be a genetic basis for OCD. If a first-

THE ROLE OF REINFORCEMENT To ease her anxiety, Melissa turned to compulsions—

Here, we see how learning can play a role in OCD. Melissa’s compulsions were negatively reinforced by the reduction in her fear. The negative reinforcement led to more compulsive behaviors, those compulsions were negatively reinforced, and so on. This learning process is ongoing and potentially very powerful. In one study, researchers monitored 144 people with OCD diagnoses for more than 40 years. The participants’ OCD symptoms improved, but almost half continued to show “clinically relevant” symptoms after four decades (Skoog & Skoog, 1999).

show what you know

Question 1

1. A behaviorist might propose that you acquire a phobia through ____________, but the maintenance of that phobia could be the result of ____________.

classical conditioning; operant conditioning

Question 2

2. People suffering from taijin kyofu tend to worry more about embarrassing others than they do about being embarrassed themselves. Yet in Western cultures, the opposite is true. What characteristics of the two cultures might lead to these differences in the expression of anxiety?

Taijin kyofu tends to occur in collectivist societies, where great emphasis is placed on the surrounding people, which might lead individuals from these societies to become overly concerned about making someone else feel uncomfortable. Collectivist cultures value social harmony over individual needs, so if you cause someone to be uncomfortable, that is worse than personal humiliation you might feel. Western cultures are more individualistic. People from these societies are much more afraid of embarrassing themselves than they are of embarrassing someone else. They tend to value their own feelings over those of others.

Question 3

3. Melissa has demonstrated recurrent all-

obsessions.

classical conditioning.

panic attacks.

compulsions.

d. compulsions.

Question 4

4. Evidence suggests there is a ____________ basis for OCD. If a first-

genetic