13.3 Behavior and Cognitive Therapies

The most famous baby in the history of psychology is probably Little Albert. At the age of 11 months, Albert developed an intense fear of rats while participating in a classic study conducted by John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner (1920). You would hope the researchers did something to reverse the effects of their ethically questionable experiment, that is, help Albert overcome his fear of rats. As far as we know, they did not. But could Albert have benefited from some form of behavior therapy?

Get to Work! Behavior Therapy

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we learned about negative reinforcement; behaviors followed by a reduction in something unpleasant are likely to recur. If anxiety is reduced as a result of avoiding a feared object, the avoidance will be repeated.

LO 6 Outline the principles and characteristics of behavior therapy.

Using the learning principles of classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning (Chapter 5), behavior therapy aims to replace maladaptive behaviors with those that are more adaptive. If behaviors are learned, who says they can’t be changed through the same mechanisms? Little Albert learned to fear rats, so perhaps he could also learn to be comfortable around them.

A classic in the history of psychology, the case study of Little Albert showed that emotional responses such as fear can be classically conditioned. Researchers John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner (1920) repeatedly exposed Albert to a frightening “bang!” every time he reached for a white rat, which led him to develop an intense fear of these animals.

exposure A therapeutic technique that brings a person into contact with a feared object or situation while in a safe environment, with the goal of extinguishing or eliminating the fear response.

A woman with arachnophobia (spider phobia) confronts the dreaded creature in a virtual environment called SpiderWorld. The goal of exposure therapy (virtual or otherwise) is to reduce the fear response by exposing clients to situations they fear. When nothing bad happens, their anxiety diminishes and they are less likely to avoid the feared situations in the future.

EXPOSURE AND RESPONSE PREVENTION To help a person overcome a fear or phobia, a behavior therapist might use exposure, a technique of placing clients in the situations they fear—

A particularly intense form of exposure is to flood a client with an anxiety-

But sometimes, it’s better to approach a feared scenario with “baby steps,” upping the exposure with each movement forward (Prochaska & Norcross, 2014). This can be accomplished with an anxiety hierarchy, which is essentially a list of activities or experiences ordered from least to most anxiety-

INFOGRAPHIC 13.2

But take note: Working up the anxiety hierarchy needn’t involve actual rodents. With technologies available today, you could put on some fancy goggles and travel into a virtual “rat world” where it is possible to reach out and “touch” that creepy crawly animal with the simple click of a rat, er . . . mouse. Virtual reality exposure therapy has become a popular way of reducing anxiety associated with various disorders, including specific phobias.

systematic desensitization A treatment that combines anxiety hierarchies with relaxation techniques.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 11, we described progressive muscle relaxation in the context of reducing the impact of responses to stress. Here, we see it can also be used to help with the treatment of phobias.

SYSTEMATIC DESENSITIZATION Therapists often combine anxiety hierarchies with relaxation techniques in an approach called systematic desensitization, which takes advantage of the fact that we can’t be relaxed and anxious at the same time. The therapist begins by teaching clients how to relax their muscles. One technique for doing this is progressive muscle relaxation, which is the process of tensing and then relaxing muscle groups, starting at the head and ending at the toes. Using this method, a client can learn to release all the tension in his body. It’s very simple—

Apply This

Sit in a quiet room in a comfortable chair. Start by tensing the muscles controlling your scalp: Hold that position for about 10 seconds and then release, focusing on the tension leaving your scalp. Next follow the same procedure for the muscles in your face, tensing and releasing. Continue all the way down to your toes and see what happens.

try this

CONNECTIONS

Classical conditioning, presented in Chapter 5, can be used to reduce alcohol consumption. Drinking alcohol is a neutral stimulus to start (one drink does not normally cause vomiting). Drinking is paired with a nausea-

Once a client has learned how to relax, it’s time to face the anxiety hierarchy (either in the real world or via imagination) while trying to maintain a sense of calm. Imagine a client who fears flying, moving through an anxiety hierarchy with her therapist. Starting with the least-

aversion therapy Therapeutic approach that uses the principles of classical conditioning to link problematic behaviors to unpleasant physical reactions.

AVERSION THERAPY Exposure therapy focuses on extinguishing or eliminating associations, but there is another behavior therapy aimed at producing them. It’s called aversion therapy. Seizing on the power of classical conditioning, aversion therapy seeks to link problematic behaviors, such as drug use or fetishes, to unpleasant physical reactions like sickness and pain (Infographic 13.2). The goal of aversion therapy is to get a person to have an involuntary—

behavior modification Therapeutic approach in which behaviors are shaped through reinforcement and punishment.

Synonyms

behavior modification applied behavior analysis

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we described how positive reinforcement (supplying something desirable) increases the likelihood of a behavior being repeated. Therapists use reinforcement in behavior modification to shape behaviors to be more adaptive.

LEARNING, REINFORCEMENT, AND THERAPY Another form of behavior therapy is behavior modification, which draws on the principles of operant conditioning, shaping behaviors through reinforcement. Therapists practicing behavior modification use positive and negative reinforcement, as well as punishment, to help clients increase adaptive behaviors and reduce those that are maladaptive. For behaviors that resist modification, therapists might use successive approximations by reinforcing incremental changes. Some will incorporate observational learning (that is, learning by watching and imitating others) to help clients change their behaviors.

token economy A treatment approach that uses behavior modification to harness the power of reinforcement to encourage good behavior.

One common approach using behavior modification is the token economy, which harnesses the power of positive reinforcement to encourage good behavior. Token economies have proven successful for a variety of populations, including psychiatric patients in residential treatment facilities and hospitals, children in classrooms, and convicts in prisons (Dickerson, Tenhula, & Green-

CONNECTIONS

Tokens are an excellent example of a secondary reinforcer. In Chapter 5, we reported that secondary reinforcers derive their power from their connection with primary reinforcers, which satisfy biological needs.

In a token economy, positive behaviors are reinforced with tokens, which can be used to purchase food, obtain privileges, and secure other desirable things. Token economies are typically used in institutions such as schools and mental health facilities.

TAKING STOCK: AN APPRAISAL OF BEHAVIOR THERAPY Because of their focus on observable behaviors occurring in the present moment, behavior therapies offer a few key advantages over insight therapies. Behavior therapies tend to work fast, producing quick resolutions to stressful situations, sometimes in a single session (Ollendick et al., 2009; Öst, 1989). And reduced time in therapy typically translates to a lower cost. What’s more, the procedures used in behavior therapy are often easy to operationalize (remember, the focus is on modifying observable behavior), so evaluating the outcome is more straightforward.

Behavior therapy has its drawbacks, of course. The goal is to change learned behaviors, but not all behaviors are learned (you can’t “learn” to have hallucinations). And because the reinforcement comes from an external source, newly learned behaviors may disappear when reinforcement stops. Finally, the emphasis on observable behavior may downplay the social, biological, and cognitive roots of psychological disorders. This narrow approach works well for treating phobias and other clear-

You Are What You Think: Cognitive Therapies

FOLLOW-

FOLLOW-

Psychologists on the reservation typically don’t have the luxury of holding more than two or three sessions with a client, so Dr. Foster has to make the most of every minute. For someone who has just received a new diagnosis, a good portion of the session is spent on psychoeducation, or learning more about a disorder: What is schizophrenia, and how will it affect my life? Dr. Foster and the client might go over some of the user-

Another main goal is to help clients restructure cognitive processes, or turn negative thought patterns into healthier ones. To help clients recognize the irrational nature of their thoughts, Dr. Foster might provide an analogy as he does here:

Dr. Foster: If we had a blizzard in February and it’s 20 degrees below for 4 days in a row, would you consider that a strange winter?

Chepa: No.

Dr. Foster: If we had a day that’s 105 degrees in August, would you consider that an odd summer?

Chepa: Well, no.

Dr. Foster: Yet you’re talking about a difference of 125 degrees, and we’re in the same place and we’re saying this is normal weather. . . . We’re part of nature. You and I are part of this natural world, and so you might have a day today where you’re very distressed, very upset, and a week from now where you’re very calm and very at peace, and both of those are normal. Both of those are appropriate.

The father of cognitive therapy, Aaron Beck, believes that distorted thought processes lie at the heart of psychological problems.

Dr. Foster might also remind Chepa that her symptoms result from her psychological condition. “Your response is a normal response [for] a human being with this [psychological disorder],” he says, “and so of course you’re scared, of course you’re upset.”

LO 7 Outline the principles and characteristics of cognitive therapy.

cognitive therapy A type of therapy aimed at addressing the maladaptive thinking that leads to maladaptive behaviors and feelings.

Dr. Foster has identified his client’s maladaptive thoughts and is beginning to help her change the way she views her world and her relationships. This is the basic goal of cognitive therapy, an approach advanced by psychiatrist Aaron Beck (1921–

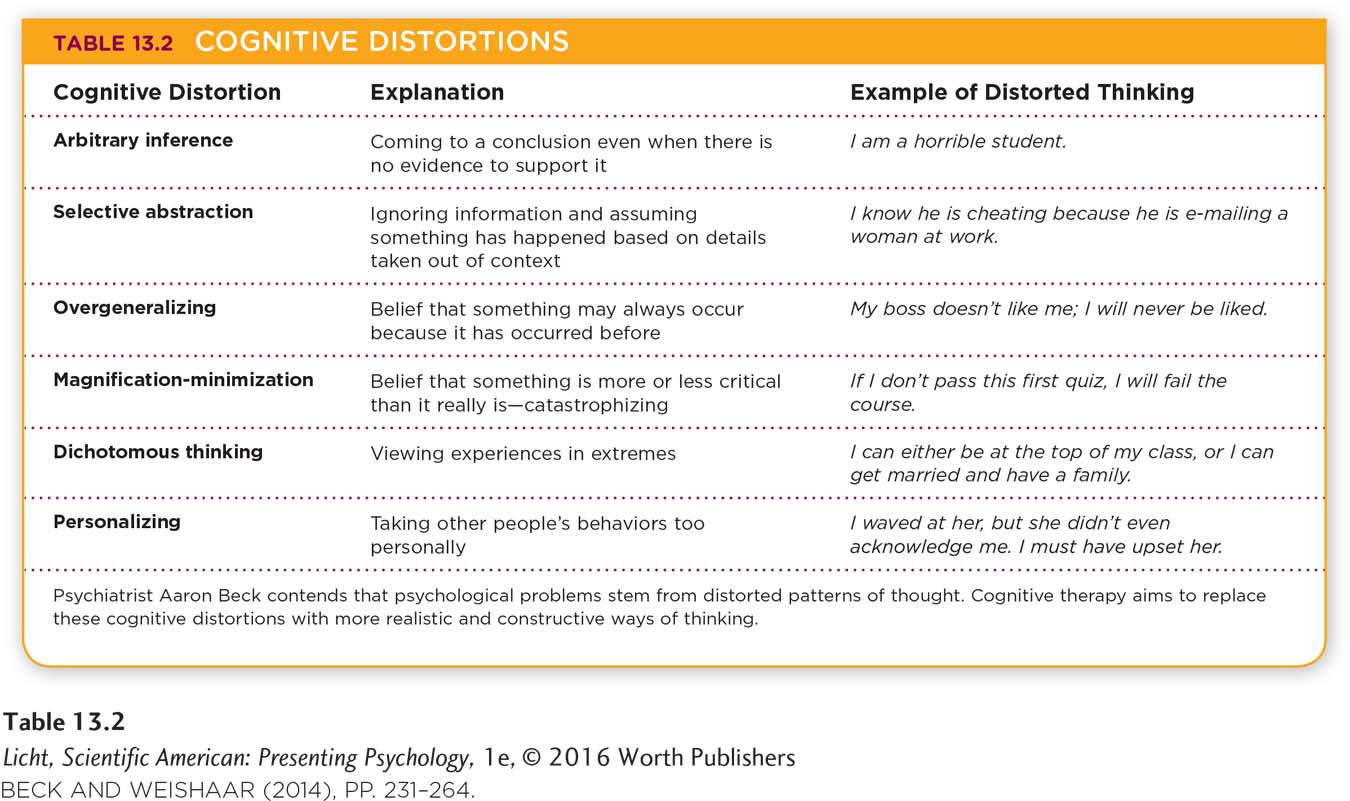

BECK’S COGNITIVE THERAPY Beck was trained in psychoanalysis, but he opted to develop his own approach after trying (without luck) to produce scientific evidence showing that Freud’s methods worked (Beck & Weishaar, 2014). Beck believes that patterns of automatic thoughts are at the root of psychological disturbances. These distortions in thinking cause individuals to misinterpret events in their lives (Table 13.2).

overgeneralization A cognitive distortion that assumes self-

Beck identified a collection of common cognitive distortions or errors associated with psychological problems such as depression (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emory, 1979). One such distortion is overgeneralization, or thinking that self-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 8, we presented Piaget’s concept of schema, a collection of ideas or notions representing a basic unit of understanding. Young children form schemas based on functional relationships they observe in the environment. Here, Beck is suggesting that schemas can also direct the way we interpret events, not always in a realistic or rational manner.

Beck suggests that cognitive schemas underlie these patterns of automatic thoughts, directing the way we interpret events. The goal is to restructure these schemas into more rational frameworks, a process that can be facilitated by client homework. For example, the therapist may challenge a client to test a “hypothesis” related to her dysfunctional thinking. (“If it’s true you don’t work effectively under male bosses, then why did your previous boss give you that highly sought-

Beck’s cognitive therapy aims to dismantle or take apart the mental frameworks harboring cognitive errors and replace them with beliefs that nurture more positive, realistic thoughts. Dr. Foster calls these mental frameworks “paradigms,” and he also tries to create a more holistic change in thinking. “I tell people that thoughts, behaviors, and words come from beliefs, and when a belief is not working for you, let’s change it,” he says. “To modify a belief doesn’t mean all or none,” he adds, “but when we outgrow a belief, that’s a wonderful time for transformation.”

rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) A type of cognitive therapy, developed by Ellis, that identifies illogical thoughts and converts them into rational ones.

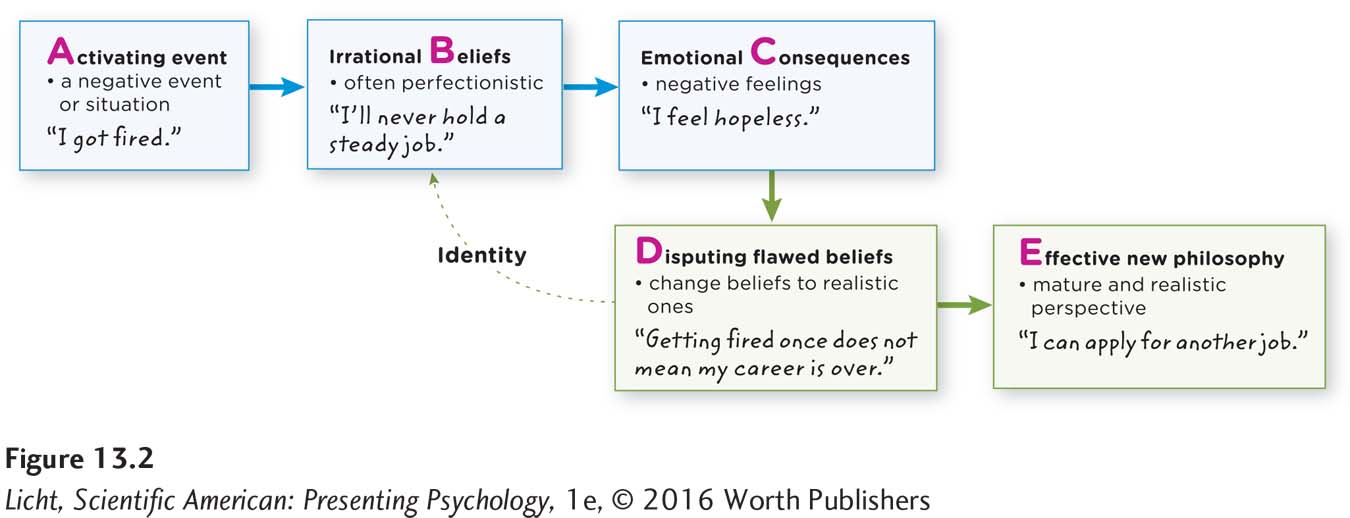

ELLIS’ RATIONAL EMOTIVE BEHAVIOR THERAPY The other major figure in cognitive therapy is psychologist Albert Ellis (1913–

The ABC’s of REBT

According to Ellis, people tend to have unrealistic beliefs, often perfectionist in nature, about how they and others should think and act. This inevitably leads to disappointment, as no one is perfect. The ultimate goal of REBT is to arrive at self-

cognitive behavioral therapy An action-

As Ellis developed his therapy throughout the years, he realized it was important to focus on cognitive processing as well as behavior. Thus, REBT therapists focus on changing both cognitions and behaviors, assigning homework to implement the insights clients gain during therapy. Because Ellis and Beck incorporated both cognitive and behavior therapy methods, their approaches are commonly referred to as cognitive behavioral therapy. Both are action-

TAKING STOCK: AN APPRAISAL OF COGNITIVE THERAPY There is considerable overlap between the approaches of Ellis and Beck. Both are short-

In some cases, cognitive models that focus on flawed assumptions and attitudes present a chicken-

All the therapies we have discussed thus far involve interactions among people. But in many cases, interpersonal therapy is not enough. The problem is rooted in the brain, and a biological solution may also be necessary.

show what you know

Question 1

1. The primary goal of _________________ therapy is to replace maladaptive behaviors with more adaptive ones.

behavior

person-

centered humanistic

psychodynamic

a. behavior

Question 2

2. Imagine you are working in a treatment facility for children, and a resident has been throwing objects at others. Using the principles of operant conditioning and observational learning, how might you use behavior modification to change this behavior?

Answers will vary, but may be based on the following information. In behavior modification, one uses positive and negative reinforcement, as well as punishment, to help a child increase adaptive behaviors and reduce those that are maladaptive. For behaviors that resist modification, therapists might use successive approximations by reinforcing incremental changes. Some therapists will incorporate observational learning (that is, learning by imitating and watching others) to help clients change their behaviors.

Question 3

3. The basic goal of _________________ is to help clients identify maladaptive thoughts and change the way they view the world and their relationships.

cognitive therapy

Question 4

4. _________________ therapy uses the ABC model to help people identify their illogical thoughts and convert them into logical ones.

Behavior

Psychodynamic

Exposure

Rational emotive behavior

d. Rational emotive behavior