14.5 It’s All Good: Prosocial Behavior, Attraction, and Love

You may be wondering why we chose to include Joe and Susanne Maggio in the same chapter as Julius Achon. What do these people have in common, and why are they featured together in a chapter on social psychology? We selected these individuals because their stories send a positive message, illuminating what is best about human relationships, like the capacity to love and feel empathy. They epitomize the positive side of social psychology.

Prosocial Behavior

LO 11 Compare prosocial behavior and altruism.

We like to believe that all human beings are capable of prosocial behavior, or behavior aimed at benefiting others. An exemplar of this ability is Julius Achon. After meeting the orphans in 2003, Julius kept his promise to assist them, wiring his family $150 a month to cover the cost of food, clothing, school uniforms, tuition, and other necessities—

As for the 11 orphans, all of them are flourishing. The teenage girl in tattered clothing—

Julius runs alongside boys and girls from the Orum primary school in Uganda’s Otuke district.

On the Up Side

altruism A desire or motivation to help others with no expectation of anything in return.

It feels good to give to others, even when you receive nothing in return. The satisfaction derived from knowing you made someone feel happier, more secure, or appreciated is enough of a reward. The desire or motivation to help others with no expectations of payback is called altruism. Empathy, or the ability to understand and recognize another’s emotional point of view, is a major component of altruism.

ALTRUISM AND TODDLERS The seeds of altruism appear to be planted very early in life. Children as young as 18 months have been observed demonstrating helping behavior. One study found that the vast majority of 18-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 11, we discussed how altruistic behaviors can reduce stress. When helping someone else, we generally don’t have time to focus on our own problems; we also see that there are people dealing with more troubling issues than we are.

REDUCING STRESS AND INCREASING HAPPINESS Research suggests that helping others reduces stress and increases happiness (Schwartz, Keyl, Marcum, & Bode, 2009; Schwartz, Meisenhelder, Yunsheng, & Reed, 2003). The gestures don’t have to be grand in order to be altruistic or prosocial. Consider the last time you bought coffee for a colleague without being asked, or gave a stranger a quarter to fill his parking meter. Do you recycle, conserve electricity, and take public transportation? These behaviors indicate an awareness of the need to conserve resources for the benefit of all. Promoting sustainability is an indirect, yet very impactful, prosocial endeavor. Perhaps you haven’t opened your home to 11 orphaned children, but you may perform acts of kindness more regularly than you realize.

Even if you’re not the type to reach out to strangers, you probably demonstrate prosocial behavior toward your family and close friends. This giving of yourself allows you to experience the most magical element of human existence: love.

Interpersonal Attraction

Joe, Kristina, and Susanne celebrate the arrival of their new family members: Joseph Jr., Michael Charles Frank, and Sophia Elizabeth. The triplets came into the world on February 11, 2013.

TO HAVE AND TO HOLD Less than a year after meeting Susanne, Joe purchased an engagement ring. He carried it around in his pocket for 3 months, and then proposed to her one morning over breakfast. They have been happily married for over 7 years. Some things have changed since that rendezvous at Chili’s 10 years ago. Joe left the ice cream business for a corporate career, little Kristina is now a teenager, and Susanne gave birth to TRIPLETS in February 2013—

TO HAVE AND TO HOLD Less than a year after meeting Susanne, Joe purchased an engagement ring. He carried it around in his pocket for 3 months, and then proposed to her one morning over breakfast. They have been happily married for over 7 years. Some things have changed since that rendezvous at Chili’s 10 years ago. Joe left the ice cream business for a corporate career, little Kristina is now a teenager, and Susanne gave birth to TRIPLETS in February 2013—

Other things remain the same, like Joe’s goofy sense of humor. He still strolls into the supermarket singing at the top of his lungs and tells people “good morning” when it’s 11 o’clock at night. “I’m a big kid,” Joe says, “but you know when it comes to my family, it’s all about making sure that they are happy and making sure that they are taken care of, and that’s my only priority in life.”

LO 12 Identify the three major factors contributing to interpersonal attraction.

interpersonal attraction The factors that lead us to form friendships or romantic relationships with others.

It seems Joe and Susanne have made a very happy life for themselves. Things can get hectic with triplet toddlers and a teen, but they seem content and able to cope with whatever challenges may arise. Joe and Susanne make a great team. How do you explain their compatibility? We suspect it has something to do with interpersonal attraction, the factors that lead us to form friendships or romantic relationships with others. What are these mysterious attraction factors? Let’s focus our attention on the three most important: proximity, similarity, and physical attractiveness.

proximity Nearness; plays an important role in the formation of relationships.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described how researchers examine relationships between two variables. A correlation does not necessarily mean one variable causes changes in the other. What other factors might be influencing friendships to develop in the classroom?

WE’RE CLOSE: PROXIMITY We would guess that the majority of people in your social circle live nearby. Proximity, or nearness, plays a significant role in the formation of our relationships. The closer two people live geographically, the greater the odds that they will meet and spend time together, and the more likely they are to establish a bond (Festinger, Schachter, & Back, 1950; Nahemow & Lawton, 1975). One study looking at the development of friendships in a college classroom setting concluded that sitting in nearby seats and being assigned to the same work groups correlated with the development of friendships (Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2008). In other words, sitting next to someone in class, or even in the same row, increases the chances that you will become friends. Would you agree?

Notions of proximity have changed since the introduction of the Internet. Thanks to applications like Skype and Google Hangouts, we can now have face-

SOCIAL MEDIA and psychology

Relationships Online

The great advantage of online dating, according to researchers, is that it broadens the dating pool, providing users with opportunities to meet people they never would encounter offline (Finkel et al., 2012). There are drawbacks, however, like the tendency for many online daters to focus on profile pictures and other superficial details. Also, don’t count on the compatibility algorithms many online dating sites advertise, as researchers are skeptical of them (Finkel, et al., 2012). Despite these shortcomings, relationships that start on these sites are surprisingly successful. According to one study, around 20% of couples who met online had formed lasting relationships, defined as married, engaged, or living together (Bargh & McKenna, 2004).

The great advantage of online dating, according to researchers, is that it broadens the dating pool, providing users with opportunities to meet people they never would encounter offline (Finkel et al., 2012). There are drawbacks, however, like the tendency for many online daters to focus on profile pictures and other superficial details. Also, don’t count on the compatibility algorithms many online dating sites advertise, as researchers are skeptical of them (Finkel, et al., 2012). Despite these shortcomings, relationships that start on these sites are surprisingly successful. According to one study, around 20% of couples who met online had formed lasting relationships, defined as married, engaged, or living together (Bargh & McKenna, 2004).

LOOKING FOR LOVE IN ELECTRONIC PLACES.

You may be wondering how social media sites such as Facebook affect interpersonal bonds. Research suggests that many people use social media to enhance the relationships they already have (Anderson, Fagan, Woodnutt, & Chamorro-

Relationships 2.0

Social networking sites play a significant role in modern relationships, particularly among young people. For many teens, communicating through sites like Facebook is an important means of cultivating relationships (Reich, Subrahmanyam, & Espinoza, 2012).

mere-

MERE-

The mere-

But here’s the flip side. Repeated negative exposures may lead to stronger distaste. If a person you frequently encounter has annoying habits or uncouth behavior, negative feelings might develop, even if your initial impression was positive (Cunningham, Shamblen, Barbee, & Ault, 2005). This can be problematic for romantic partners. All those minor irritations you overlooked early in the relationship can evolve into major headaches.

SIMILARITY Perhaps you have heard the saying “birds of a feather flock together.” This statement alludes to the concept of similarity, another factor that contributes to interpersonal attraction (Moreland & Zajonc, 1982; Morry, Kito, & Ortiz, 2011). We tend to prefer those who share our interests, viewpoints, ethnicity, values, and other characteristics. Even age, education, and occupation tend to be similar among those who are close (Lott & Lott, 1965).

PHYSICAL ATTRACTIVENESS We probably don’t need to tell you that physical attractiveness plays a major role in interpersonal attraction (Eastwick, Eagly, Finkel, & Johnson, 2011; Lou & Zhang, 2009). But here is the question: Is beauty really in the eye of the beholder? In other words, do people from different cultures and historical periods have different concepts of beauty? There is some degree of consistency in the way people rate facial attractiveness (Langlois et al., 2000), with facial symmetry generally considered an attractive trait (Grammer & Thornhill, 1994). But certain aspects of beauty do appear to be culturally distinct (Gangestad & Scheyd, 2005). In some parts of the world, people go to great lengths to elongate their necks, increase height, pierce their bodies, augment their breasts, enlarge or reduce the size of their waists, and paint themselves—

LOOKING GOOD IN THOSE GENES: THE EVOLUTIONARY PERSPECTIVE Why is physical attractiveness so important? Beauty is a sign of health, and healthy people have greater potential for longevity and successful breeding (Gangestad & Scheyd, 2005). Consider this evidence: Women are more likely to seek out men with healthy-

Clearly, women can be swayed by the good looks of potential mates. But which gender places greater value on beauty? And what other characteristics do men and women seek in long-

CONTROVERSIES

Are You My Natural Selection?

From an evolutionary standpoint, men and women produce offspring for the same reason—

From an evolutionary standpoint, men and women produce offspring for the same reason—

A WOMAN’S FINANCIAL SECURITY HAS BECOME AN INCREASINGLY IMPORTANT CRITERION FOR MALE SUITORS.

Do people really choose partners according to these criteria? One study of over 10,000 participants from 37 cultures concluded that women around the world do indeed favor mates who appear to be good providers, whereas men place greater value on good looks and youth (Buss, 1989). Subsequent studies have produced similar results (Buss, Shackelford, Kirkpatrick, & Larsen, 2001; Schwarz & Hassebrauck, 2012; Shackelford, Schmitt, & Buss, 2005).

Sure, we all have preferences for the type of partner we want, but do they really impact the choices we make? Do men, for instance, typically marry women who are younger? Yes, this appears to be the case. Husbands across the world are, on average, a few years older than their wives (Buss, 1989; Lakdawalla & Schoeni, 2003; Otta, da Silva Queiroz, de Sousa Campos, da Silva, & Silveira, 1999).

But let’s put these findings in perspective. Two or three years is not much of a gap if you’re thinking about growing old together. (Is age 83 really any different from 80?) And we all know there are many women in search of “hot men,” and men in pursuit of “sugar mamas.” Over the past several decades, in fact, a woman’s financial security has become an increasingly important criterion for male suitors (Buss et al., 2001). In today’s ever-

BEAUTY PERKS We have discussed beauty in the context of romantic relationships, but how does physical appearance affect other aspects of social existence? Generally speaking, physically attractive people seem to have more opportunities. Beauty is correlated with how much money someone makes, the type of job she holds, and overall success (Pfeifer, 2012). Good-

Beauty may captivate you in the beginning stages of a relationship, but other characteristics and qualities gain importance as time goes along. Think about the type of person you want for a life partner. Whom would you want to hold your hand when you’re sick in the hospital—

What Is Love?

In America, we are taught to believe that love is the foundation of marriage. People in Western cultures do tend to marry for love, but this is not the case everywhere. In Harare, Zimbabwe, for example, people might also marry for reasons associated with the needs of the family, such as maintaining alliances and social status (Wojcicki, van der Straten, & Padian, 2010). Similarly, many marriages in India and other parts of South Asia are arranged by family members. Love may not be present in the beginning stages of such unions, but it can blossom.

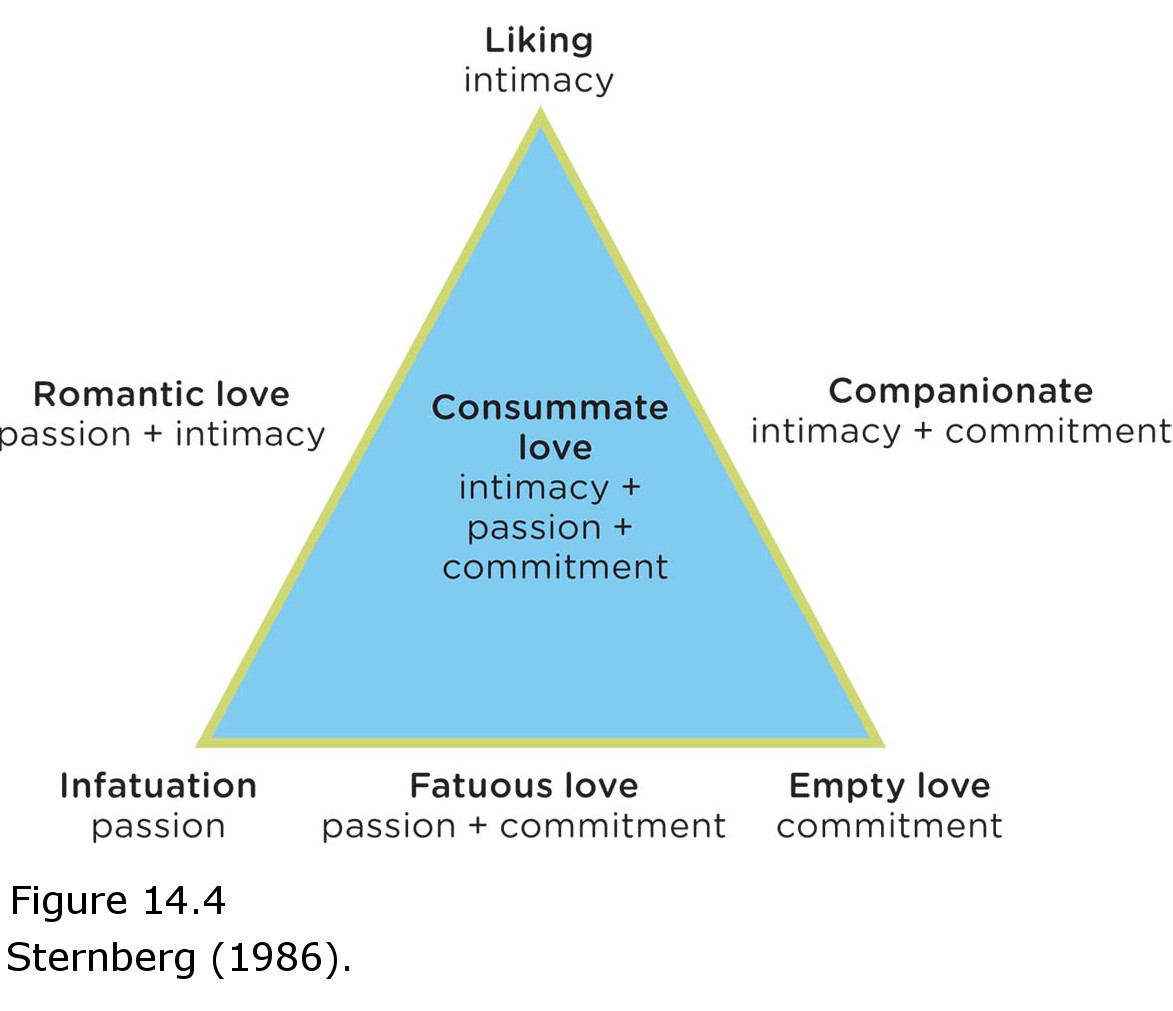

Sternberg proposed that there are different kinds of love resulting from combinations of three elements: passion, intimacy, and commitment. The ideal form, consummate love, combines all three elements.

STERNBERG’S THEORY OF LOVE In a pivotal study published in 1986, Robert Sternberg proposed that love is made up of three elements: passion (feelings leading to romance and physical attraction); intimacy (feeling close); and commitment (the recognition of love). He conceptualized these elements in terms of the corners of a triangle (Figure 14.4). Love takes many forms according to Sternberg, and can include any combination of the three elements.

romantic love Love that is a combination of connection, concern, care, and intimacy.

passionate love Love that is based on zealous emotion, leading to intense longing and sexual attraction.

companionate love Love that consists of profound fondness, camaraderie, understanding, and emotional closeness.

consummate love (kän(t)-sə-mət) Love that combines intimacy, commitment, and passion.

Many relationships begin with exhilaration and intense physical attraction, and then evolve into more intimate connections. This is the type of love we often see portrayed in the movies. The combination of connection, concern, care, and intimacy is what Sternberg called romantic love. Romantic love is similar to what some psychologists refer to as passionate love (also known as “love at first sight”), which is based on zealous emotion, leading to intense longing and sexual attraction (Hatfield, Bensman, & Rapson, 2012). As a relationship grows, intimacy and commitment develop into companionate love, or love that consists of profound fondness, camaraderie, understanding, and emotional closeness. Companionate love is typical of a couple that has been together for many years. They become comfortable with each other, routines set in, and passion often fizzles (Aronson, 2012). Although the passion may wane, the friendship is strong. Consummate love (kän(t)-sə-mət) is evident when intimacy and commitment are accompanied by passion. The ultimate goal is to maintain all three components of the triangle.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we discussed sensory adaptation, which refers to the way in which sensory receptors become less sensitive to constant stimuli. In Chapter 5, we presented the concept of habituation, which occurs when an organism becomes less responsive to repeated stimuli. Humans seem to be attracted to novelty, which might underlie our desire for passion.

Research and life experiences tell us that relationships inevitably change. Romantic love is generally what drives people to commit to one another (Berscheid, 2010). But the passion associated with this stage generally decreases over time. That does not mean it cannot reemerge, however. Can you think of ways this passion might be rekindled—

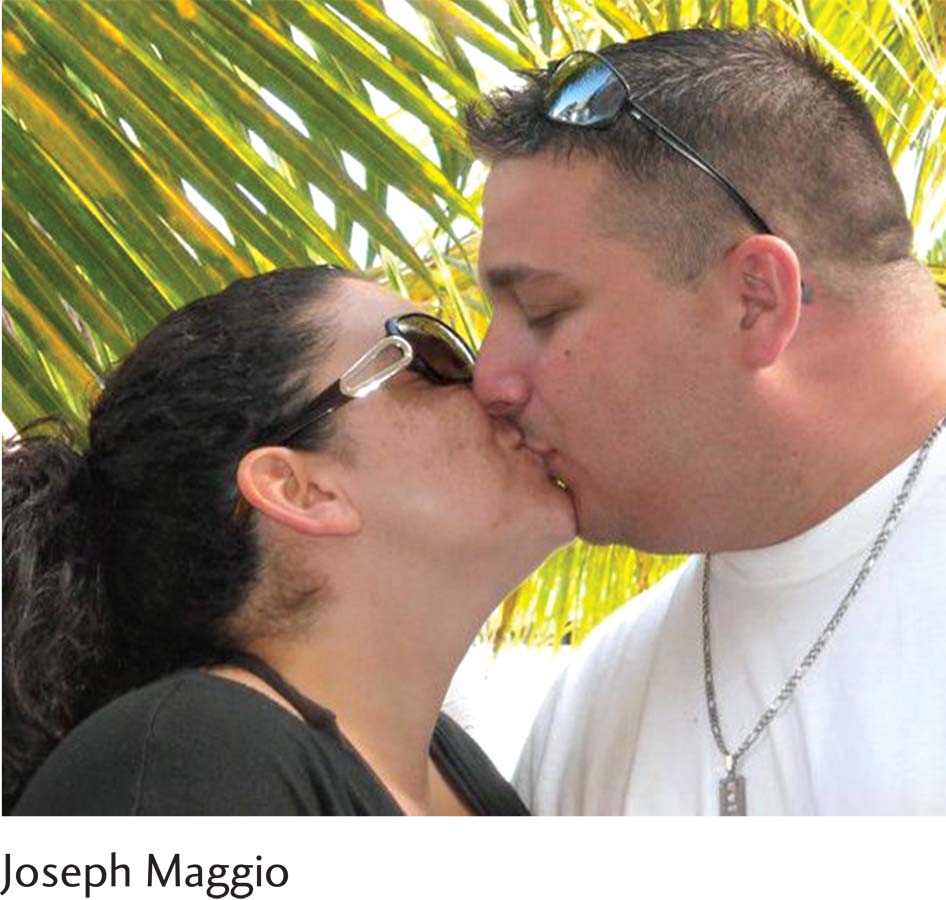

What type of love do you think online dating sites tend to select for? Is it companionate love (SF loves to garden, looking for someone who . . .)? Or is it passionate love (SM looking for a good time with no strings attached . . .)? As Joe can attest, passionate love was present from the beginning of his relationship with Susanne (he jokes about taking a few cold showers before anything happened). Although their passion is still strong and steady, the love and respect they have for one another have grown much deeper.

After several years of marriage and three new children, the love between Joe and Susanne Maggio is stronger than ever. They have what you might call consummate love, a type of love characterized by intimacy, commitment, and passion.

Have you ever wondered about the long-

MAKING THIS CHAPTER WORK IN YOUR LIFE At last, we reach the end of our journey through social psychology. We hope that what you have learned in this chapter will come in handy in your everyday social exchanges. Be conscious of the attributions you use to explain the behavior of others—

show what you know

Question 1

1. Julius Achon sent money home every month to help cover the cost of food, clothing, and schooling for his 11 adopted children. This is a good example of:

the just-

world hypothesis. deindividuation.

individualistic behavior.

prosocial behavior.

d. prosocial behavior.

Question 2

2. What are the three major factors that play a role in interpersonal attraction?

social influence; obedience; physical attractiveness

proximity; similarity; physical attractiveness

obedience; proximity; social influence

proximity; love; social influence

b. proximity, similarity, physical attractiveness

Question 3

3. We described how the investment model of commitment can be used to predict the long-

According to this model, decisions to stay together or part ways are based on how happy people are in their relationship, their notion of what life would be like without it, and their investment in the relationship. People may stay in unsatisfying or unhealthy relationships if they feel there are no better alternatives or believe they have too much to lose. This model helps us understand why people remain in destructive relationships. These principles also apply to friendships, positions at work, or loyalty to institutions.