9.1 Motivation

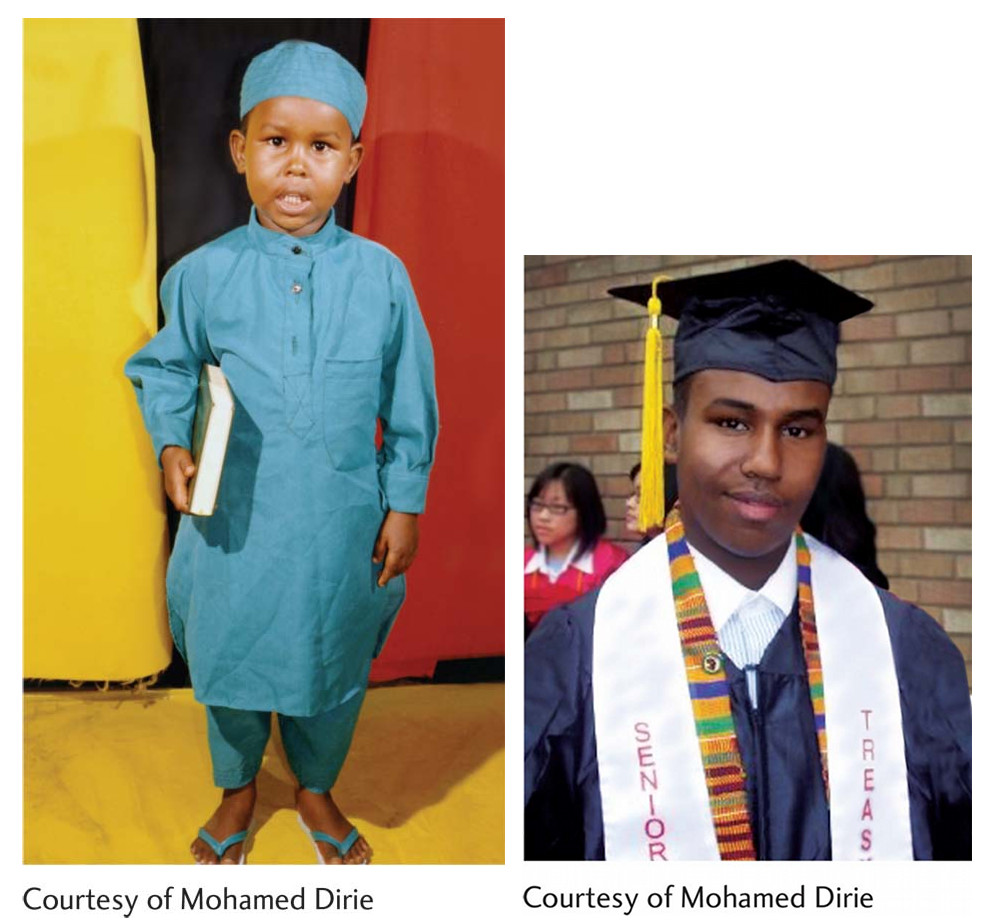

FIRST DAY OF SCHOOL When Mohamed Dirie started first grade, he did not know his ABCs or 123s. He had no idea what the words “teacher,” “cubby,” or “recess” meant. In fact, he spoke virtually no English. As for his classmates, they were beginning first grade with basic reading and writing skills from preschool and kindergarten. Mohamed’s early education had taken place in an Islamic school, where he spent most of his time learning to read and recite Arabic verses of the Qur’an (kə-ˈrän). But Arabic wasn’t going to be much help to a 6-

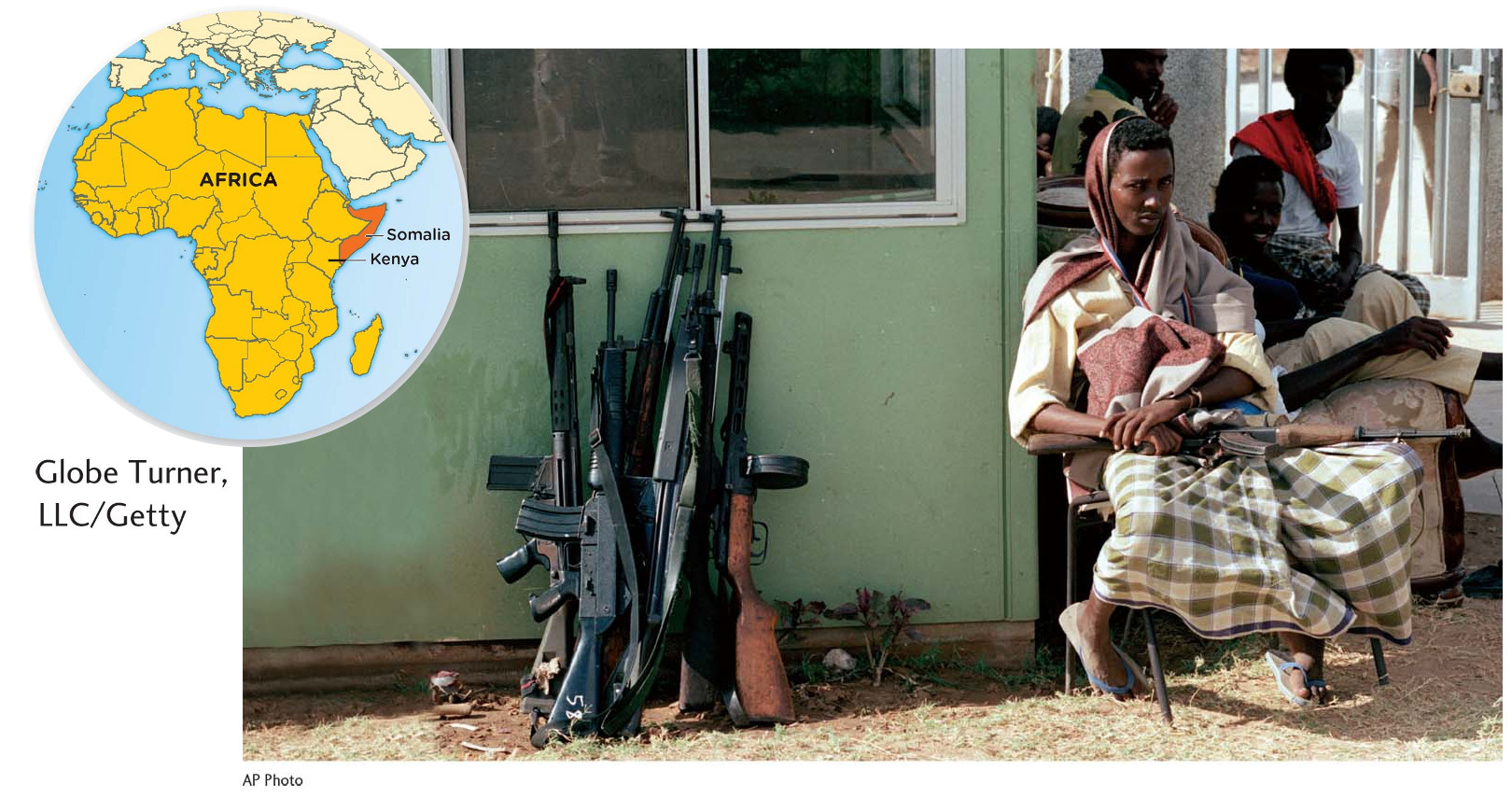

Months earlier, Mohamed and his mother, father, and older sister had arrived in St. Paul from the East African nation of Kenya, some 8,000 miles across the globe. Kenya was not their native country, just a stopping point between their homeland, Somalia, and a new life in America.

Perhaps you have heard about Somalia. Many of the news stories coming out of this nation in the past two decades have told of bloody clashes between rival factions, kidnappings by pirates, suicide bombings, and starving children. Somalia’s serious troubles began in 1991, when rebel forces overthrew the government of President Siad Barre. With gunshots ringing through the streets of their home city of Mogadishu, Mohamed’s family, like thousands of others, fled the country, narrowly escaping death.

Mohamed’s family comes from the East African nation of Somalia (shaded red on the map). They fled their homeland in 1991 during a violent government overthrow that led to more than 20,000 civilian deaths (Gassmann, 1991, December 21). The image here shows a group of Somali rebels in the capital city of Mogadishu about a month after the regime was toppled.

Note: Quotations attributed to Mohamed Dirie are personal communications.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

LO 1 Define motivation.

LO 2 Explain how extrinsic and intrinsic motivation impact behavior.

LO 3 Summarize instinct theory.

LO 4 Describe drive-

LO 5 Explain how arousal theory relates to motivation.

LO 6 Outline Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

LO 7 Discuss how the stomach and the hypothalamus make us feel hunger.

LO 8 Outline the characteristics of the major eating disorders.

LO 9 Describe the human sexual response as identified by Masters and Johnson.

LO 10 Define sexual orientation and summarize how it develops.

LO 11 Identify the most common sexually transmitted infections.

LO 12 Define emotions and explain how they are different from moods.

LO 13 List the major theories of emotion and describe how they differ.

LO 14 Discuss evidence to support the idea that emotions are universal.

LO 15 Indicate how display rules influence the expression of emotion.

LO 16 Describe the role the amygdala plays in the experience of fear.

LO 17 Summarize evidence pointing to the biological basis of happiness.

Four-

The first day of school in St. Paul, little Mohamed strapped on his backpack and walked with his mother to the bus stop. When the yellow bus pulled up to the curb, Mohamed’s mother followed him inside and insisted on accompanying him to school. But Mohamed was ready to make the journey alone. “No, Mom, I got this,” he remembers saying in his native Somali.

When Mohamed arrived at his new school, he found his way to the first-

By the end of third grade, he had graduated from an English as a Second Language (ESL) program and could converse fluently with classmates. He sailed through the rest of elementary school with As and Bs in all subjects. Middle school presented new challenges, as Mohamed attended one of the poorest schools in the district and occasionally got picked on, but he continued to excel academically, taking the most challenging classes offered. In high school, he took primarily international baccalaureate (IB) or pre-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 7, we described intellectually gifted people as those with very high IQ scores. We also presented the concept of emotional intelligence. Here, we see that in addition to intelligence, motivation plays a role in success.

If you think about where Mohamed began and where he is today, it’s hard not to be awed. He entered the United States’ school system 2 years behind his peers, unable to speak a word of English, an outsider in a culture radically different from his own. Without any tutoring from his parents (who couldn’t read the class assignments, let alone help him with schoolwork), he managed to propel himself to the upper levels of the nation’s educational system in just 12 years.

How do you explain Mohamed’s success? This young man definitely is intelligent. You can tell he is bright after 5 minutes of conversation. But intelligence is not the only ingredient in the recipe for outstanding achievement. Other factors are important as well, including something psychologists consider essential for success in school: motivation (Conley, 2012; Hodis, Meyer, McClure, Weir, & Walkey, 2011; Linnenbrink & Pintrich, 2002).

What Is Motivation?

There are people who get kicks from bungee jumping out of helicopters, and those who feel completely invigorated by a rousing match of chess. Human behaviors can be logical: We eat when hungry, sleep when tired, and go to work to pay the rent. Our behaviors can also be senseless and destructive: A beautiful fashion model starves herself, or an aspiring politician throws away an entire career for a fleeting sexual adventure. Why do people spend their hard-

One way to explain human behavior is through learning. We know that people (not to mention dogs, chickens, and slugs) can learn to behave in certain ways through classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning (Chapter 5). But learning isn’t everything. Another way to explain behavior is to consider what might be motivating it. In the first half of this chapter, you will learn about different forms of motivation and the theories explaining them. Keep in mind that human behavior is complex and should be studied in the context of culture, biology, and the environment. Every behavior is likely to have a multitude of causes (Maslow, 1943).

LO 1 Define motivation.

motivation A stimulus that can direct behavior, thinking, and feeling.

Psychologists propose that motivation is a stimulus or force that can direct the way we behave, think, and feel. A motivated behavior tends to be guided (that is, it has a direction), energized, and persistent. Mohamed’s academic behavior has all three features: guided because he sets specific goals like getting into graduate school, energized because he goes after those goals with zeal, and persistent because he sticks with his goals even when challenges arise.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we introduced positive and negative reinforcers, which are stimuli that increase future occurrences of target behaviors. In both cases, the behavior becomes associated with the reinforcer. Here, we see how these associations become incentives.

incentive An association established between a behavior and its consequences, which then motivates that behavior.

INCENTIVE Let’s take a look at how operant conditioning, particularly the use of reinforcers, can help us understand the relationship between learning and motivation. When a behavior is reinforced (with positive or negative reinforcers), an association is established between the behavior and its consequence. If we consider motivated behavior, this association becomes the incentive, or reason to repeat the behavior. Imagine there is a term paper you have been avoiding. You decide you will treat yourself to an hour of Web surfing for every three pages you write. Adding a reinforcer (surf time) increases your writing behavior; thus, we call it a positive reinforcer. The association between the behavior (writing) and the consequence (Web surfing) is the incentive. Before you know it, you begin to expect this break from work, which motivates you to write.

LO 2 Explain how extrinsic and intrinsic motivation impact behavior.

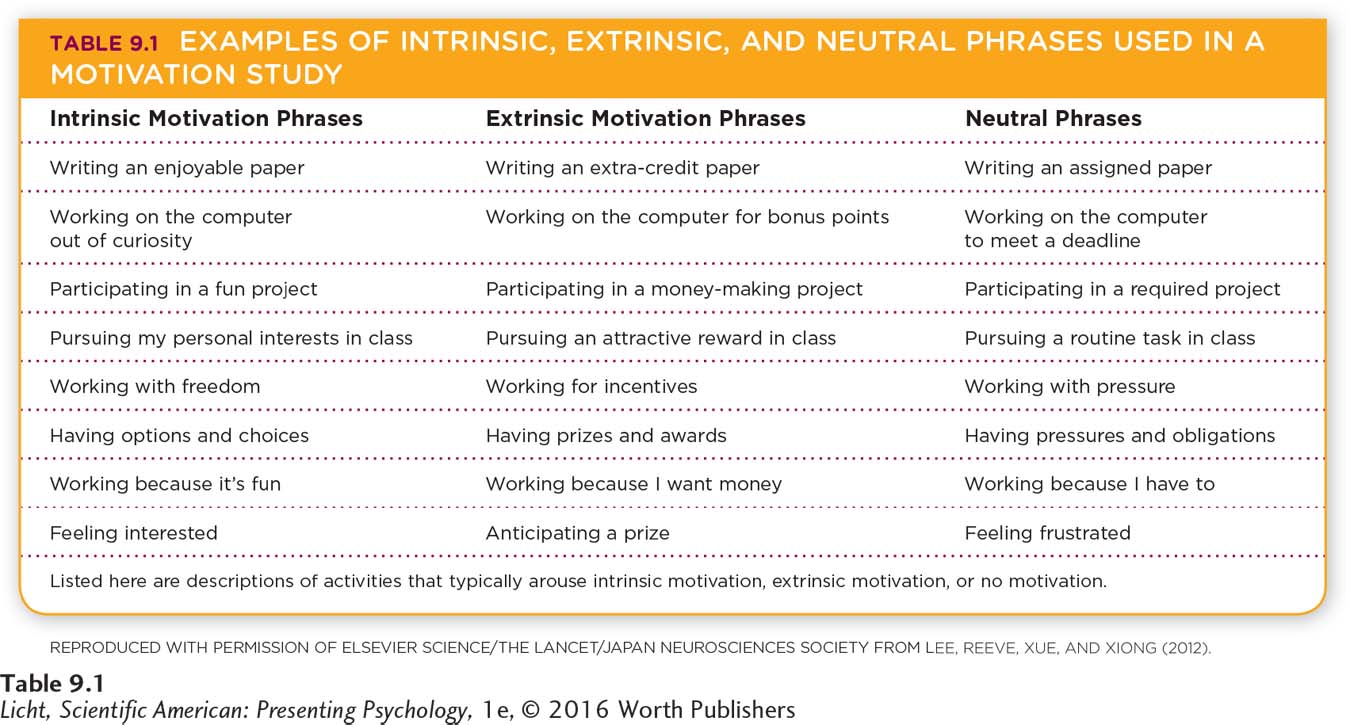

extrinsic motivation The drive or urge to continue a behavior because of external reinforcers.

EXTRINSIC MOTIVATION When a learned behavior is motivated by the incentive of external reinforcers in the environment, we would say there is an extrinsic motivation to continue that behavior (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999; Table 9.1). In other words, the motivation comes from consequences that are found in the environment or situation. Bagels and coffee might provide extrinsic motivation for people to attend a boring meeting. Sales commissions provide extrinsic motivation for sales people to sell more goods. For most of us, money serves as a powerful form of extrinsic motivation.

intrinsic motivation The drive or urge to continue a behavior because of internal reinforcers.

INTRINSIC MOTIVATION But learned behaviors can also be motivated by personal satisfaction, interest in a subject matter, and other variables that exist within a person. When the urge to continue a behavior comes from within, we call it intrinsic motivation (Deci et al., 1999). Reading a textbook because it is inherently interesting exemplifies intrinsic motivation. The reinforcers originate inside of you (learning feels good and brings you satisfaction), and not from the external environment.

What compels you to offer your seat to an older adult on a bus: Is it because you’ve been praised for helping others before (extrinsic motivation), or because it simply feels good to help someone (intrinsic motivation)? Perhaps your response is a combination of both.

Why are some people drawn to thrill-

EXTRINSIC VERSUS INTRINSIC Many behaviors are inspired by a blend of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation, but there do appear to be potential disadvantages to extrinsic motivation (Deci et al., 1999). Researchers have found that using rewards, such as money and marshmallows, to reinforce already interesting activities (like doing puzzles, playing word games, and so on) can lead to a decrease in what was initially intrinsically motivating. Perhaps the use of external reinforcers causes people to feel less responsible for initiating their own behaviors.

In general, behavior resulting from intrinsic motivation is likely to include “high-

For Mohamed, the most powerful source of extrinsic motivation was the approval of his mother. He recalls how proud she was after returning from a parent–

Instinct Theory

GOODBYE, SOMALIA Somalia was not a safe place in 1991. The groups that orchestrated the revolution began warring among themselves, and the country plunged into bloody chaos. Over 20,000 innocent people were killed in the crossfire (Gassmann, 1991, December 21). A famine and food crisis ensued, which, in addition to the ongoing fighting, led to 240,000 to 280,000 deaths within the next 2 years (Gundel, 2003). It is easy to understand why Mohamed’s parents, or anyone, would want to remove their family from Somalia during this period. Faced with a life-

GOODBYE, SOMALIA Somalia was not a safe place in 1991. The groups that orchestrated the revolution began warring among themselves, and the country plunged into bloody chaos. Over 20,000 innocent people were killed in the crossfire (Gassmann, 1991, December 21). A famine and food crisis ensued, which, in addition to the ongoing fighting, led to 240,000 to 280,000 deaths within the next 2 years (Gundel, 2003). It is easy to understand why Mohamed’s parents, or anyone, would want to remove their family from Somalia during this period. Faced with a life-

LO 3 Summarize instinct theory.

instincts Complex behaviors that are fixed, unlearned, and consistent within a species.

A group of starving Somalis hope to receive food from an aid center in the city of Bardera. The situation in Somalia turned to chaos and desperation after rebels toppled the government in 1991. Over 240,000 people died in the ensuing war and famine (Gundel, 2003).

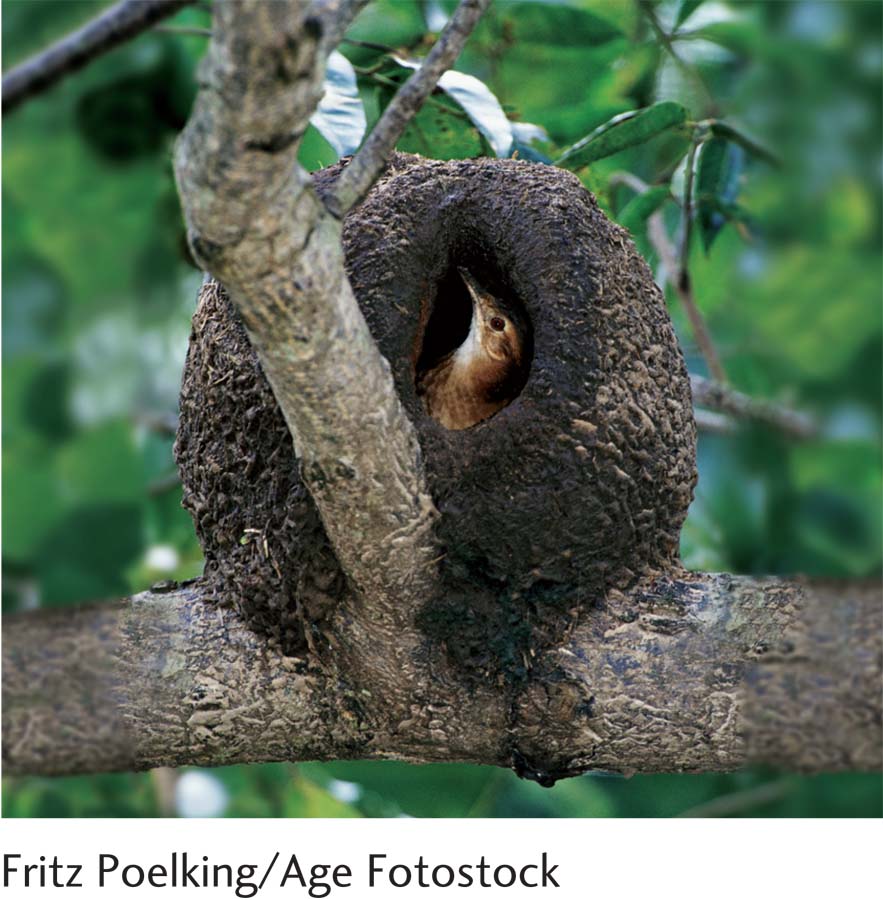

What are instincts, do humans really have them, and how do they relate to motivation? First observed by scientists studying animals, instincts are complex behaviors that are fixed, unlearned, and consistent within a species. Instincts motivate South American ovenbirds to construct elaborate cavelike nests, and sea turtles to swim back hundreds of miles to feeding grounds they visited years earlier (Broderick, Coyne, Fuller, Glen, & Godley, 2007). No one teaches the birds to build their nests or the turtles to retrace migratory routes; through evolution, these behaviors appear to be etched into their genetic make-

Instincts form the basis of one of the earliest theories of motivation. Inspired in part by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, early scholars proposed that humans have a variety of instincts (McDougall, 1912). American psychologist William James (1890/1983) suggested we could explain some human behavior through instincts such as attachment and cleanliness. At the height of instinct theory’s popularity, several thousand human “instincts” had been named, among them curiosity, flight, and aggressiveness (Bernard, 1926; Kuo, 1921). Yet there was little evidence they were true instincts—

South American ovenbirds build cozy cavelike nests using mud, grass, and bark. Elaborate home-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we presented the evolutionary perspective, which suggests humans have evolved adaptive traits through natural selection. Behaviors that improve the chances of survival and reproduction are most likely to be passed along to offspring, whereas less adaptive behaviors decrease in frequency. Humans do appear to have innate responses that have been shaped by our ancestors’ behaviors.

Although instinct theory faded into the background, some of its themes are apparent in the evolutionary perspective. A substantial body of research suggests that evolutionary forces influence human behavior. For example, emotional responses, such as fear of snakes, heights, and spiders, may have evolved to protect us from danger (Plomin, DeFries, Knopik, & Neiderhiser, 2013). But these fears are not instincts, because they are not universal. Not everyone is afraid of snakes and spiders; some of us have learned to fear (or not fear) them through experience. When trying to pin down the motivation for behavior, it is difficult to determine the relative contributions of learning (nurture) and innate factors (nature) such as instinct (Deckers, 2005).

Habiba Ibrahim hauls wood to build a new home near Baidoa, Somalia, in December 1993. The 30-

FOUR YEARS IN KENYA After fleeing the bullet-

FOUR YEARS IN KENYA After fleeing the bullet-

Being an outsider in Kenya was not easy, however. Back in Somalia, Mohamed’s father had earned a solid living constructing buildings, and his mother had been a successful entrepreneur selling homemade food from their house. In Kenya, neither parent could find employment. They had no choice but to live off “remittances,” or money sent from family members outside of Africa, and relying on other people was not their style. “You’re waiting on other people to feed you,” Mohamed says, “and [my father] didn’t like that.”

Daily life presented its fair share of challenges, too. Mohamed’s diet was painfully monotonous, with most meals centering around ugali, a dense gruel made of corn or millet flour—

Drive-Reduction Theory

needs Physiological or psychological requirements that must be maintained at some baseline or constant state.

homeostasis The tendency for bodies to maintain constant states through internal controls.

Humans and nonhuman animals have basic physiological needs or requirements that must be maintained at some baseline or constant state to ensure continued existence. Homeostasis refers to the way in which our bodies maintain these constant states through internal controls. In order to survive, there is a continuous monitoring of oxygen, fluids, nutrients, and other physiological variables. If these fall below desired or necessary levels, an urge to restore equilibrium surfaces. And this urge motivates us to act.

LO 4 Describe drive-

drive-

drive A state of tension that pushes us or motivates behaviors to meet a need.

The drive-

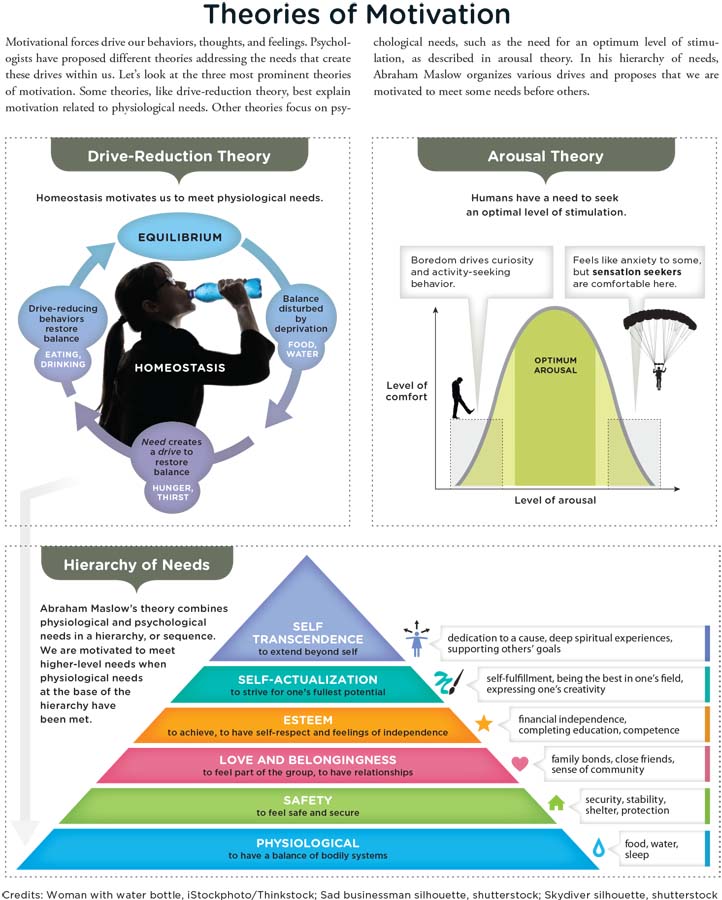

INFOGRAPHIC 9.1

Let’s look at another concrete example of drive reduction. Imagine you visit a mountainous area 6,500 feet above sea level, which puts a strain on breathing. While jogging, you find yourself gasping for air because your oxygen levels have dropped. Motivated by the need to maintain homeostasis, you stop what you are doing until your oxygen levels return to normal. Having an unfulfilled need (not enough oxygen) creates a drive (state of tension) that pushes you to modify your behavior in order to restore homeostasis (you stop and breathe deeply, allowing your blood oxygen levels to return to a normal level). The drive-

Arousal Theory

Mohamed arrived in America when he was 6 years old. Stepping off the plane in the Twin Cities (Minneapolis/St. Paul) was quite a shock for a young boy who had lived most of his childhood in the crowded, pavement-

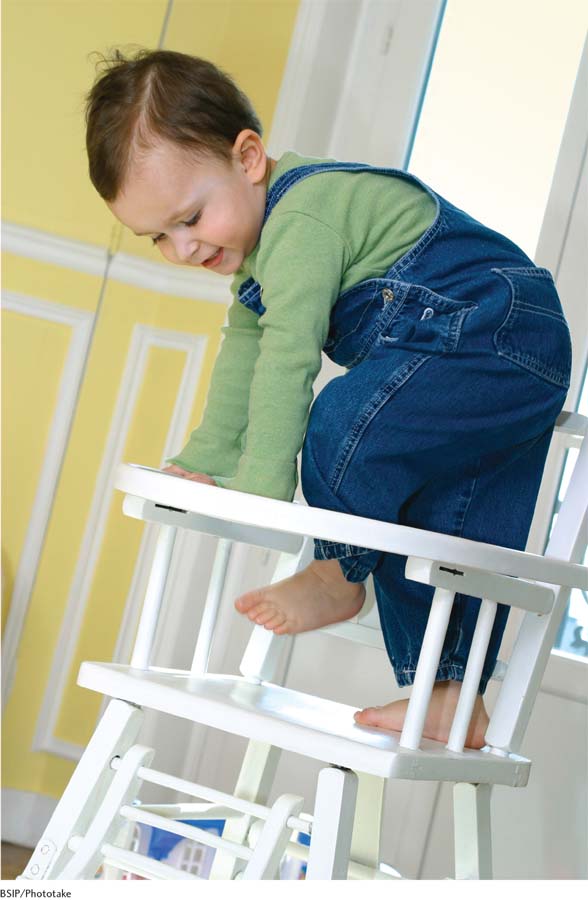

Babies and toddlers are notorious for climbing on furniture, mouthing nonfood items, and reaching for hazardous objects (this is why many parents “baby proof” their homes). Like adults looking for exciting places to travel and new electronic gadgets to own, these babies may be searching for novel forms of stimulation.

New places, people, and experiences can be frightening. They can also be delightfully exhilarating. Humans are fascinated by novelty, and you see evidence of this innate curiosity in the earliest stages of life. Babies grab, suck, and climb on just about everything they can get their hands on, including (much to the horror of their parents) dangerous electrical devices. Ignoring the most forceful parental warnings (Do NOT touch that hot plate!), many toddlers still reach out and touch extremely hot cookware or recklessly leap between pieces of furniture. But mind you, children are not the only ones seeking new experiences. Grown men and women will pay hundreds of dollars to parachute out of airplanes or float over jagged mountains in hot-

Our primate cousins are also inquisitive, which suggests that they too have an innate need for enrichment and sensory stimulation. Researchers have found that monkeys will attempt to open latches without extrinsic motivation; apparently, their curiosity motivates their behavior (Butler, 1960; Harlow, Harlow, & Meyer, 1950).

LO 5 Explain how arousal theory relates to motivation.

arousal theory Suggests that humans are motivated to seek an optimal level of arousal, or alertness and engagement in the world.

According to arousal theory, humans (and perhaps other primates) seek an optimal level of arousal, as not all motivation stems from physical needs. Arousal, or engagement in the world, can be a product of anxiety, surprise, excitement, interest, fear, and many other emotions. Have you ever had an unexplained urge to make simple changes to your daily routines, like taking a new route to work, preparing your morning eggs differently, or adding new clothes to your wardrobe? These behaviors may stem from your need to increase arousal, as optimal arousal is a personal or subjective matter that is not the same for everyone (Infographic 9.1). Evidence suggests that some people are sensation seekers; that is, they appear to seek activities that increase arousal (Zuckerman, 1979, 1994). Popularly known as “adrenaline junkies,” these individuals relish activities like cliff diving, racing motorcycles, and watching horror movies. High sensation seeking is not necessarily a bad thing, as it may be associated with a higher tolerance for stressful events (Roberti, 2004).

Needs and More Needs: Maslow’s Hierarchy

LO 6 Outline Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

hierarchy of needs A continuum of needs that are universal and ordered in terms of the strength of their associated drives.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed Maslow and his involvement in humanistic psychology. The humanists suggest that people are inclined to grow and change for the better, and this perspective is apparent in the hierarchy of needs. Humans are motivated by the universal tendency to move up the hierarchy and meet needs toward the top.

Have you ever been in a car accident, lived through a hurricane, or witnessed a violent crime? At the time, you probably were not thinking about what show you were going to watch on HBO that night. When physical safety is threatened, everything else tends to take a backseat. This is one of the themes underlying the hierarchy of needs theory of motivation proposed by Abraham Maslow (1908–

PHYSIOLOGICAL NEEDS Physiological needs, as stated earlier, include the requirements for food, water, sleep, and an overall balance of bodily systems. If a life-

SAFETY NEEDS For most North Americans, basic physiological needs are “relatively well gratified” (Maslow, 1943), and thus Maslow would suggest their behavior is motivated by the next higher level in the hierarchy: safety needs. But how you define safety depends on the circumstances of your life. If you were living in Mogadishu during the 1991 revolution (and many times subsequent to that period), staying safe might have involved dodging bullets and artillery fire. For those currently living in Somalia, safety includes having access to safe drinking water and disease-

LOVE AND BELONGINGNESS NEEDS If safety needs are being met, then people will be motivated by love and belongingness needs. Maslow suggested this includes the need to avoid loneliness, to feel like part of a group, and to maintain affectionate relationships. Except for a rare run-

We all want to belong, and failing to meet this need has significant consequences. People who feel disconnected or excluded may demonstrate less prosocial behavior (Twenge, Baumeister, DeWall, Ciarocco, & Bartels, 2007) and behave more aggressively and less cooperatively, which only tends to intensify their struggle for social acceptance (DeWall, Baumeister, & Vohs, 2008).

Relationships with friends help fulfill what Maslow called love and belongingness needs.

ESTEEM NEEDS If the first three levels of needs are being met, then the individual might be motivated by esteem needs, including the need to be respected by others, to achieve, and to have self-

self-

SELF-

Iraqi families gather for Iftar, the evening meal eaten after the daytime fast. During the holy month of Ramadan, Muslims foreswear food and water from dawn to dusk. They also step up charity work and other efforts to help those less fortunate (Huffington Post, 2012, July 16). Here, basic needs (food and water) are put on hold for something more transcendent.

SELF-

EXCEPTIONS TO THE RULE Maslow’s hierarchy provides suggestions for the order of needs, but this sequence is not set in stone. In some cases, people abandon physiological needs in order to meet a self-

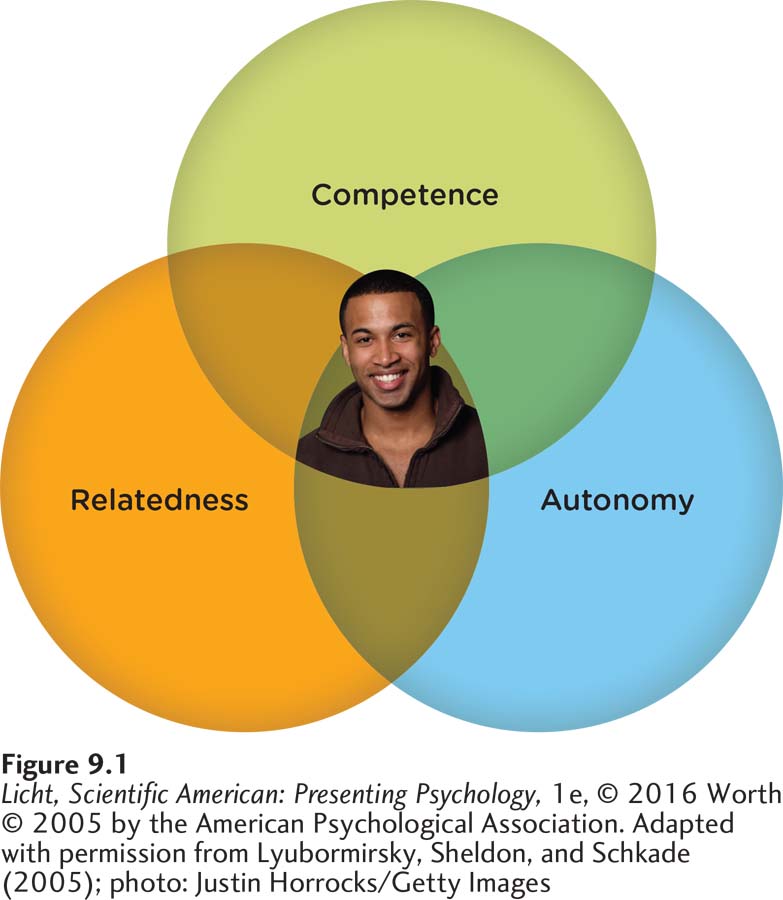

Deci and Ryan’s theory proposes that we are born with fundamental needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy.

Safety is another basic need often relegated in the pursuit of something more transcendent. Just think of all the soldiers who have given their lives fighting for causes like freedom and social justice. Somali parents living in a war zone and battling hunger may neglect their own basic needs to ensure their children’s well-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 8, we introduced Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development, which suggests that stages of development are marked by a task or emotional crisis. These crises often touch on issues of competence, relatedness, and autonomy.

self-

SELF-

need for achievement (n-

NEED FOR ACHIEVEMENT In the early 1930s, Henry Murray proposed that humans are motivated by 20 fundamental human needs. One of these has been the subject of a great deal of research: the need for achievement (n-

need for power (n-

NEED FOR POWER According to McClelland and colleagues (1976), some people are motivated by a need for power (n-

SOCIAL MEDIA and psychology

Network Needs

Some of the most enthusiastic users of Facebook—

Some of the most enthusiastic users of Facebook—

Social media users are driven by the desire for love and belonging (the third level from the bottom on Maslow’s hierarchy). Facebook seems to appeal to people who struggle to get those needs met in real life (Song et al., 2014), but it may not be the answer to their problems. One study of college students, for example, found no evidence that using Facebook eliminated loneliness. Those who were socially isolated offline were also socially isolated online (Freberg, Adams, McGaughey, & Freberg, 2010). In some cases, using social media actually intensified feelings of loneliness (DiSalvo, 2010, January/February). Perhaps this is because interactions with network “friends” tend to be more superficial than those in real life. Can anyone really maintain deep and meaningful relationships with 300 Facebook friends?

FACEBOOK: A CURE FOR LONELINESS?

But there is a bright side. Facebook does appear to be a useful tool for strengthening established relationships (DiSalvo, 2010). A century ago, families were not as geographically scattered as they are today. Grandparents, siblings, and cousins might have lived in the same town or county, and this would have created more opportunities for love, affection, and belonging. These days, families are dispersed all over the globe, and staying connected through social media may be a lot easier (and cheaper) than buying airplane tickets.

In the next section, we return our focus to the base of Maslow’s pyramid, where basic drives such as hunger and thirst are represented. Sadly, many people in the world do not get those needs fulfilled.

show what you know

Question 1

1. ____________ is a stimulus that directs the way we behave, think, and feel.

Motivation

Question 2

2. Imagine you are a teacher trying to motivate your students. Explain why you would want them to be influenced by intrinsic motivation as opposed to extrinsic motivation.

Answers will vary. Extrinsic motivation is the drive or urge to continue a behavior because of external reinforcers. Intrinsic motivation is the drive or urge to continue a behavior because of internal reinforcers. A teacher wants to encourage intrinsic motivation because the reinforcers originate inside of the students, through personal satisfaction, interest in a subject matter, and so on. There are some potential disadvantages to extrinsic motivation. For example, using rewards, such as money and candy, to reinforce already interesting activities can lead to a decrease in what was intrinsically motivating. Thus, the teacher would want students to respond to intrinsic motivation because the tasks themselves are motivating, and the students love learning for the sake of learning itself.

When activities are not novel or challenging or do not have aesthetically pleasing characteristics, intrinsic motivation will not be useful. Thus, using rewards might be the best way to motivate these types of activities.

Question 3

3. Your instructor suggests that gender differences in dating behavior are ultimately motivated by evolutionary forces. She is using which of the following to support her explanation?

operant conditioning

arousal theory

instinct theory

homeostasis

c. instinct theory

Question 4

4. The ____________ theory of motivation suggests that the need to maintain homeostasis motivates us to meet our biological needs.

arousal

instinct

incentive

drive-

reduction

d. drive-

Question 5

5. According to Maslow, the biological and psychological needs that motivate us to behave are arranged in a ____________.

hierarchy of needs

Question 6

6. How does drive-

The drive-