9.5 Types of Emotions

Imagine the whirlwind of emotions you would feel if you witnessed a loved one being attacked by a shark. Fear is probably the most obvious, but there are others, including anger toward the shark, disgust at the sight of blood, anxiety about the outcome, gratitude toward those who came to the rescue, and guilt (it should have been me).

Are such feelings common to all people? Some researchers have proposed that there is a set of “biologically given” emotions, which includes anger, fear, disgust, sadness, and happiness (Coan, 2010). These types of feelings are considered basic emotions because people all over the world experience and express them in similar ways; they appear to be innate and have an underlying neural basis (Izard, 1992). The fact that children born deaf and blind have the same types of expressions of emotion (happiness, anger, and so on) suggests the universal nature of such displays (Hess & Thibault, 2009).

It is also noteworthy that unpleasant emotions (fear, anger, disgust, and sadness) have survived throughout our evolutionary history, and are more prevalent than positive emotions such as happiness, surprise, and interest (Ekman, 1992; Forgas, 2008; Izard, 2007). This suggests that negative emotions have “adaptive value”; in other words, they may be useful in dangerous situations, like those that demand a fight-

The Biology of Fear

The 1975 movie Jaws was America’s first “summer blockbuster.” Jaws told the tale of a great white shark that stalked beachgoers in a summer vacation spot. So frightening were the film’s story and imagery that many Americans stopped going to the beach that summer (BBC, 2001, November 16).

LO 16 Describe the role the amygdala plays in the experience of fear.

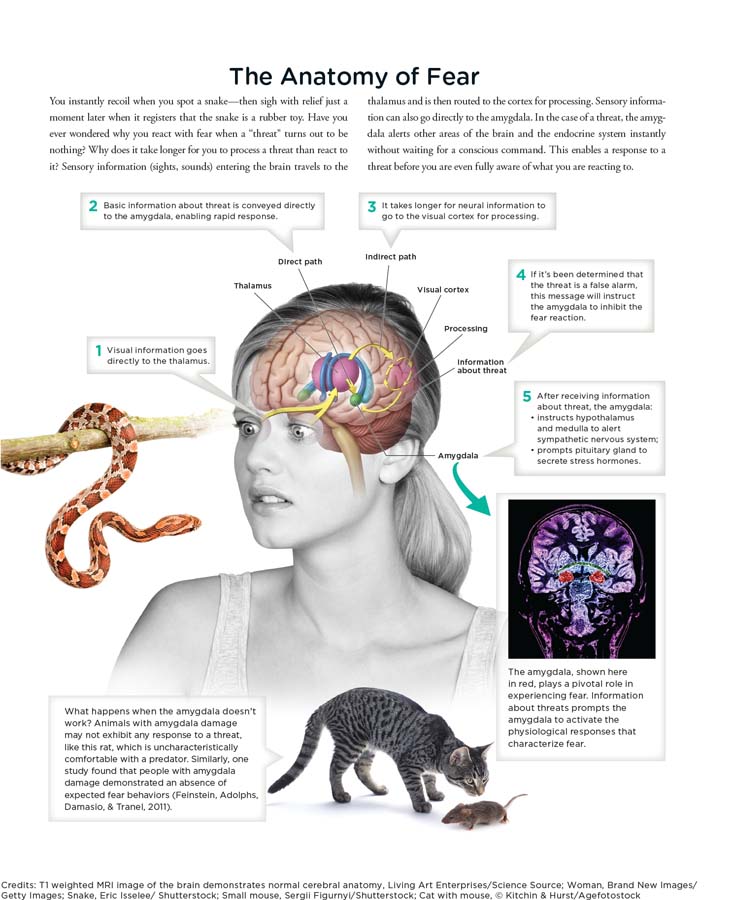

Have you ever wondered what takes place in your brain when you feel afraid? Researchers certainly have. With the help of brain-

PATHWAYS TO FEAR What exactly does the amygdala do? When confronted with a fear-

The snake-

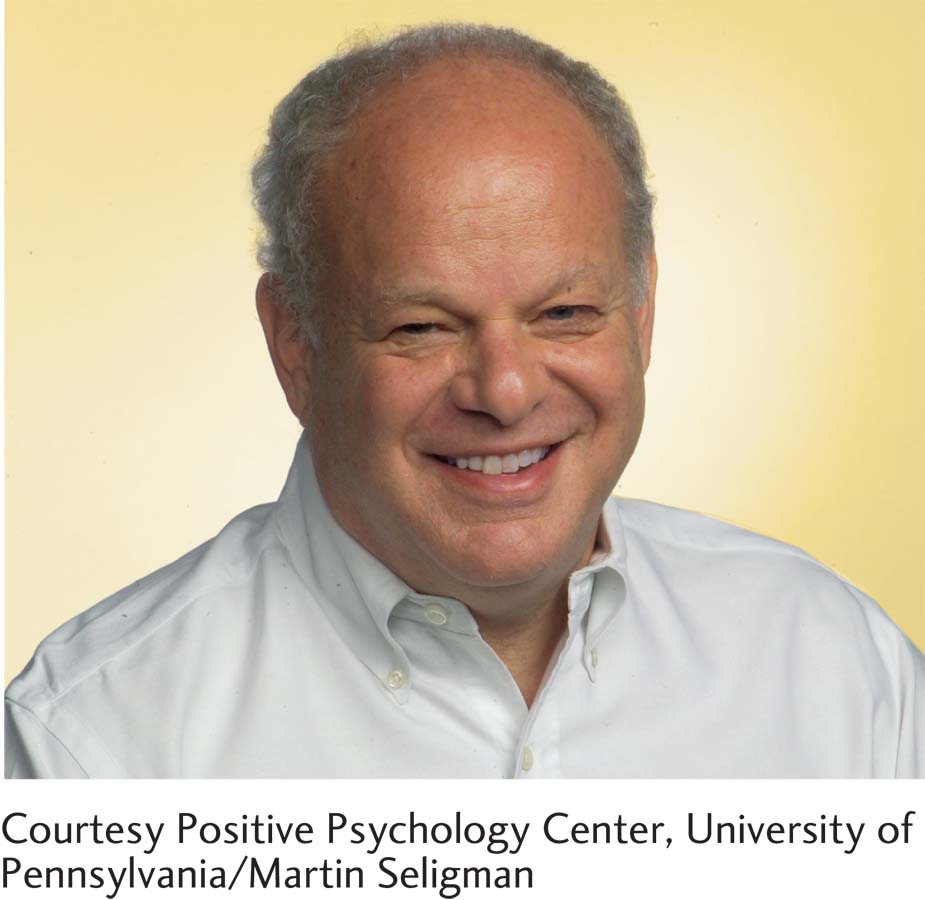

Psychologist Martin Seligman is a leading proponent of positive psychology, which emphasizes the goodness and strength of the human spirit. Getting the most out of life, according to Seligman, means not only pursuing happiness, but also cultivating relationships, achieving goals, and being deeply engaged in meaningful activities (Szalavitz, 2011, May 13).

INFOGRAPHIC 9.4

EVOLUTION AND FEAR LeDoux (2012) suggested an evolutionary advantage to having direct and indirect routes for processing information about potential threats. The direct route (thalamus to amygdala, causing an emotional reaction) enables us to react quickly to threats for which we are biologically prepared (snakes, spiders, aggressive faces). The other pathway allows us to evaluate more complex threats (such as nuclear weapons, job layoffs) with our cortex, overriding the fast-

The amygdala also plays an important role in the creation of “emotional memories,” which are fairly robust and detailed (Johnson, LeDoux, & Doyère, 2009; LeDoux, 2002). This is useful because we are more likely to survive if we remember threats in our environments. For some people, however, emotional memories cause troublesome fear and anxiety (Chapter 11).

What other evidence points to the evolutionary benefit of fear and other emotions? Research suggests that the biological response patterns accompanying emotions are both innate and universal (they appear to be preprogrammed and shared by all). These patterns are the same irrespective of gender or age, although responses in older adults tend to be less extreme (Levenson, Carstensen, Friesen, & Ekman, 1991).

Happiness

In the very first chapter of this book, we introduced the field of positive psychology, “the study of positive emotions, positive character traits, and enabling institutions” (Seligman & Steen, 2005, p. 410). Rather than focusing on mental illness and abnormal behavior, positive psychology emphasizes human strengths and virtues. The goal is well-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 8, we described several temperaments exhibited by infants. Around 40% of infants can be classified as easy babies who follow regular schedules, are relatively happy, easy to soothe when upset, and quick to adjust to changes in the environment. The existence of such a temperament lends support to the biological basis of happiness discussed here.

LO 17 Summarize evidence pointing to the biological basis of happiness.

THE BIOLOGY OF HAPPINESS To what degree do we inherit happiness? Happiness has heritability estimates between 35% and 50%, and as high as 80% in longitudinal studies (Nes, Czajkowski, & Tambs, 2010). In other words, we can explain a high proportion of the variation in happiness, life satisfaction, and well-

Research suggests that the biological basis of happiness may include a “set point,” similar to the set point for body weight (Bartels et al., 2010; Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade, 2005). Happiness tends to fluctuate around a fixed level (this point is the degree of happiness we experience when we are not trying to be happier). As we strive for personal happiness, it is important to recognize the strength of this set point, which is influenced by genes and temperament. But do not lose hope; researchers also suggest it is possible to increase happiness over time (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005).

In Chapter 5, we presented the concept of habituation, a basic form of learning in which repeated exposure to an event generally results in a reduced response. Here, we see the same effect can occur with events that result in happiness. With repeated exposure, we will habituate to an event that initially elicited happiness.

INCREASING HAPPINESS In general, positive events in our lives only seem to bring temporary happiness (Diener, Lucas, & Scollon, 2006; Mancini, Bonanno, & Clark, 2011). Why is this? We tend to become habituated to new feelings of happiness or a new level of happiness rather quickly. If you win the lottery, get a new job, or buy a beautiful house, you will likely experience an increased level of happiness for a while, but then go back to your baseline, or “set point,” of happiness (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). Things that feel new and improved or life-

Apply This

There are many steps you can take to increase your level of happiness. Engaging in physical exercise, showing kindness, and getting involved in activities that benefit others are all linked to increased positive emotions (Lyubomorsky et al., 2011; Walsh, 2011). The same can be said for recording positive thoughts and feelings of gratefulness in a journal. One group of researchers asked participants to write down in a diary those aspects of their lives for which they were grateful each day. The researchers measured well-

Gender and Emotions

Urban myth, common sense, stereotypes, and our daily experiences in North America all lead us to believe that men and women experience and express their emotions differently, but is this true? Are women really more “emotional” than men? Do men hide their emotions? In a study that set out to examine some of these beliefs, participants were shown pictures of faces expressing emotions such as anger, happiness, and sadness (Barrett & Bliss-

Mohamed got married in 2011, became a father in 2012, and graduated from the University of Minnesota in 2013. He now has two children (a boy and a girl) and is working as an Information Technology Analyst at the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority.

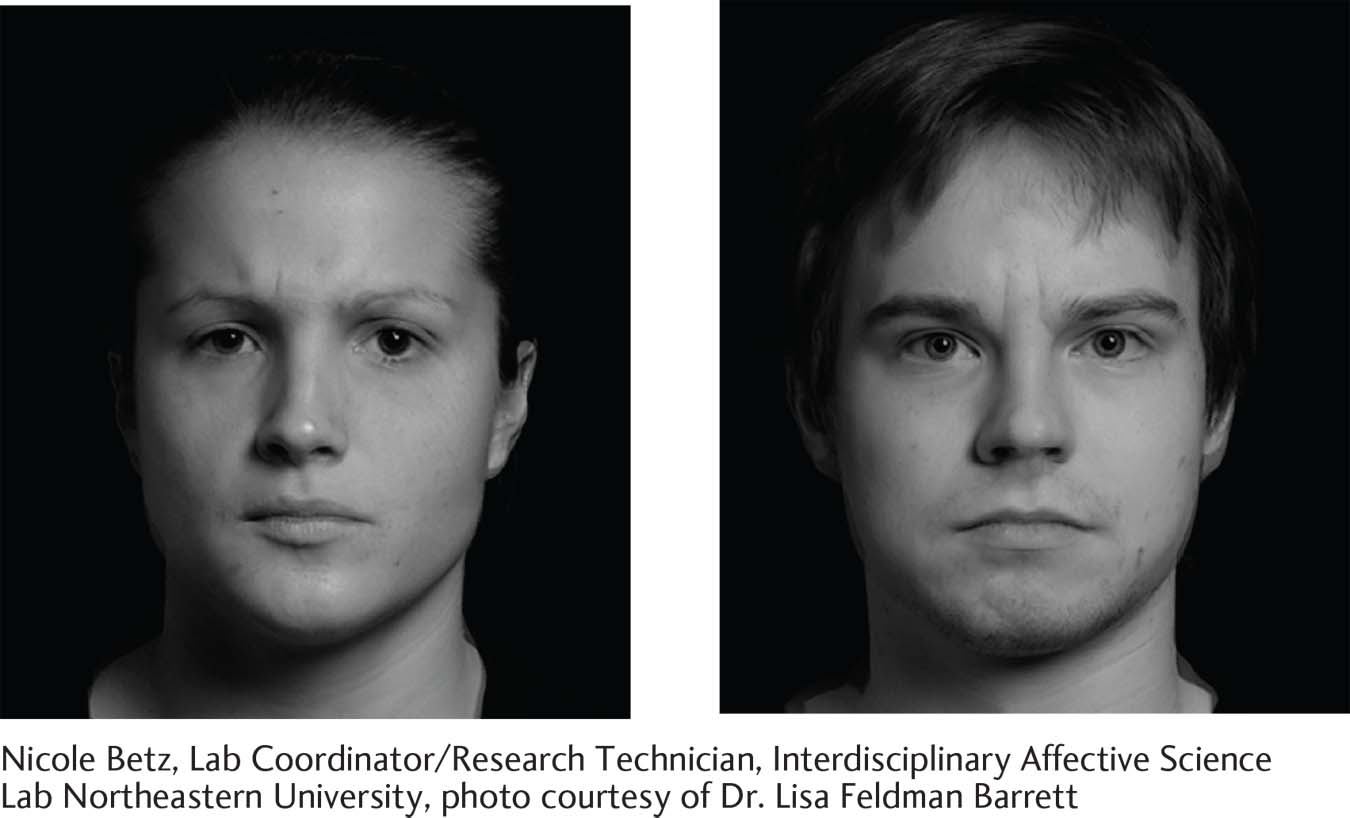

Both of these individuals appear angry, but why are they feeling this way? Research suggests that people are more likely to attribute a woman’s unpleasant expression to her “emotional” disposition and a man’s angry face to “having a bad day.” These assumptions rest on the stereotype that women are more emotional than men.

The gender differences suggested by the participants’ beliefs are not necessarily accurate, however. Most psychologists studying this topic suggest that men and women are more similar than different when it comes to experiencing and expressing emotion (Else-

That being said, research has uncovered some interesting gender disparities related to emotion. Some evidence suggests that women tend to feel more guilt, shame, and embarrassment than men (Else-

show what you know

Question 1

1. Researchers have found that when people view images that are threatening, or when they see images of faces of people who are afraid, the ____________ becomes active.

amygdala

Question 2

2. How would you explain to a fellow student what the following statement means: Happiness has heritability estimates as high as 80%?

Heritability is the degree to which heredity is responsible for a particular characteristic in a population. In this case, the heritability for happiness is as high as 80%, indicating that around 80% of the variation in happiness can be attributed to genes, and 20% to environmental influences. In other words, we can explain a high proportion of the variation in happiness, life satisfaction, and well-

Question 3

3. When confronted by a potential threat, such as a shark, your heart starts pounding, your breathing speeds up, and your pupils dilate. These changes are activated by

the cognitive appraisal approach.

the cortex.

the sympathetic nervous system.

gender differences.

c. the sympathetic nervous system.