Individual Differences in Emotion and Its Regulation

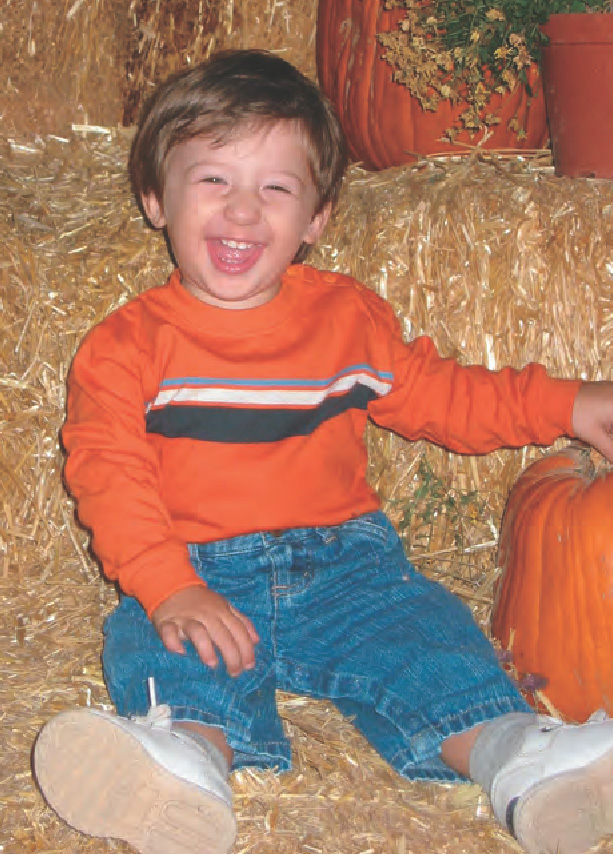

Although the overall development of emotions and self-regulatory capabilities is roughly similar for most children, there also are very large individual differences in children’s emotional functioning. Some infants and children are relatively mellow: they do not become upset easily and they usually do not have difficulty calming down when they are upset. Other children are quite emotional; they get upset quickly and intensely, and their negative emotion persists for a long time. Moreover, children differ in their timidity, in their expression of positive emotion, and in the ways they deal with their emotions. Compare these two 3-year-old children, Maria and Bruce, as they react to Teri, an adult female stranger:

When Teri walks over to Maria and starts to talk with her, Maria smiles and is eager to show Teri what she is doing. When Teri asks Maria if she would like to go down the hall to the play room (where experiments are conducted), Maria jumps up and takes Teri’s hand.

In contrast, when Teri walks over to Bruce, Bruce turns away. He doesn’t talk to her and averts his eyes. When Teri asks him if he wants to play a game, Bruce moves away, looks timid, and softly says “no.”

(N. Eisenberg, laboratory observations)

Children also vary in the speed with which they express their emotions, as illustrated by the differences in these two preschool boys:

When someone crosses Taylor, his wrath is immediate. There is no question how he is feeling, no time to correct the situation before he erupts. Douglas, though, seems almost to consider the ongoing emotional situation. One can almost see annoyance building until he finally sputters, “Stop that!”

(Denham, 1998, p. 21)

The differences among children in their emotionality and regulation of emotion almost certainly have a basis in heredity. For example, identical twins are more similar to each other in these aspects of their emotion and regulation than are fraternal twins (Rasbash et al., 2011; Saudino & Wang, 2012). However, environmental stressors, including factors as diverse as negative parenting and instability in an adopted child’s placement (E. E. Lewis et al., 2007), are related to problems children may have with self-regulation and the expression of emotion. Undoubtedly, a combination of genetic and environmental factors jointly contributes to individual differences in children’s emotions and related behaviors (C. S. Barr, 2012; Rasbash et al., 2011; Saudino & Wang, 2012).

403

Temperament

temperament  constitutionally based individual differences in emotional, motor, and attentional reactivity and self-regulation that demonstrate consistency across situations, as well as relative stability over time

constitutionally based individual differences in emotional, motor, and attentional reactivity and self-regulation that demonstrate consistency across situations, as well as relative stability over time

Because infants differ so much in their emotional reactivity, even from birth, it is commonly assumed that children are born with different emotional characteristics. Differences in various aspects of children’s emotional reactivity that tend to emerge early in life are labeled as dimensions of temperament. Mary Rothbart and John Bates, two leaders in the study of temperament, define temperament as

constitutionally based individual differences in emotional, motor, and attentional reactivity and self-regulation. Temperamental characteristics are seen to demonstrate consistency across situations, as well as relative stability over time.

(Rothbart & Bates, 1998, p. 109)

Although characteristics of temperament have generally been thought to be evident fairly early in life, there is now evidence that some may not emerge until childhood or adolescence and may change considerably at different ages (Saudino & Wang, 2012; Shiner et al., 2012). For example, incentive motivation—the vigor and rate of responding to anticipated rewards—seems to become stronger in early adolescence, which may account for reduced self-regulation in regard to rewarding but risky activities (e.g., the use of drugs and alcohol), and then drops after adolescence (Luciana & Collins, 2012; Luciana et al., 2012). Changes in when and how much temperament is expressed at different ages likely occur because genes switch on and off throughout development, so there are changes in the degree to which behaviors are affected by genes (Saudino & Wang, 2012).

The phrase “constitutionally based” in Rothbart and Bates’s definition of temperament refers, of course, to genetically inherited characteristics. But it also refers to aspects of biological functioning, such as neural development and hormonal responding, that can be affected by the environment during the prenatal period and after birth. For example, nutritional deficiencies or exposure to cocaine during the prenatal period (T. Dennis et al., 2006), maternal stress and anxiety during pregnancy (Huizink, 2008, 2012), and a premature birth (C. A. C. Clark et al. 2008) all appear to have the potential to affect infants’ and young children’s ability to regulate their attention and behavior. Similar negative effects can result from sustained elevations of cortisol (a stress-related hormone that activates energy reserves) because of maternal insensitivity or child abuse during the early years of life (Bugental, Martorell, & Barraza, 2003; Gunnar & Cheatham, 2003). Thus, the construct of temperament is highly relevant to our themes of individual differences and the role of nature and nurture in development.

The pioneering work in the field of temperament research was the New York Longitudinal Study, conducted by Alexander Thomas and Stella Chess (Thomas & Chess, 1977; Thomas, Chess, & Birch, 1968). These researchers began by interviewing a sample of parents, repeatedly and in depth, about their infants’ specific behaviors. To reduce the possibility of bias in the parents’ reports, the researchers asked that instead of interpretive characterizations, such as “he’s often cranky” or “she’s interested in everything,” the parents provide detailed descriptions of their infant’s specific behaviors. On the basis of those interviews, nine characteristics of children were identified, including such traits as quality of mood, adaptability, activity level, and attention span and persistence. Further analyzing the interview results in terms of these characteristics, the researchers classified the infants into three groups: easy, difficult, and slow-to-warm-up.

404

- Easy babies adjusted readily to new situations, quickly established daily routines such as sleeping and eating, and generally were cheerful in mood and easy to calm.

- Difficult babies were slow to adjust to new experiences, tended to react negatively and intensely to novel stimuli and events, and were irregular in their daily routines and bodily functions.

- Slow-to-warm-up babies were somewhat difficult at first but became easier over time as they had repeated contact with new objects, people, and situations.

In the initial study, 40% of the infants were classified as easy, 10% as difficult, and 15% as slow-to-warm-up. The rest did not fit into one of these categories. Of particular importance, some dimensions of children’s temperament showed relative stability over time, with temperament in infancy predicting how children were doing years later. For example, “difficult” infants tended to have problems with adjustment at home and at school, whereas few of the “easy” children had such problems. (We will return to the issue of stability of temperament and its social and emotional correlates shortly.)

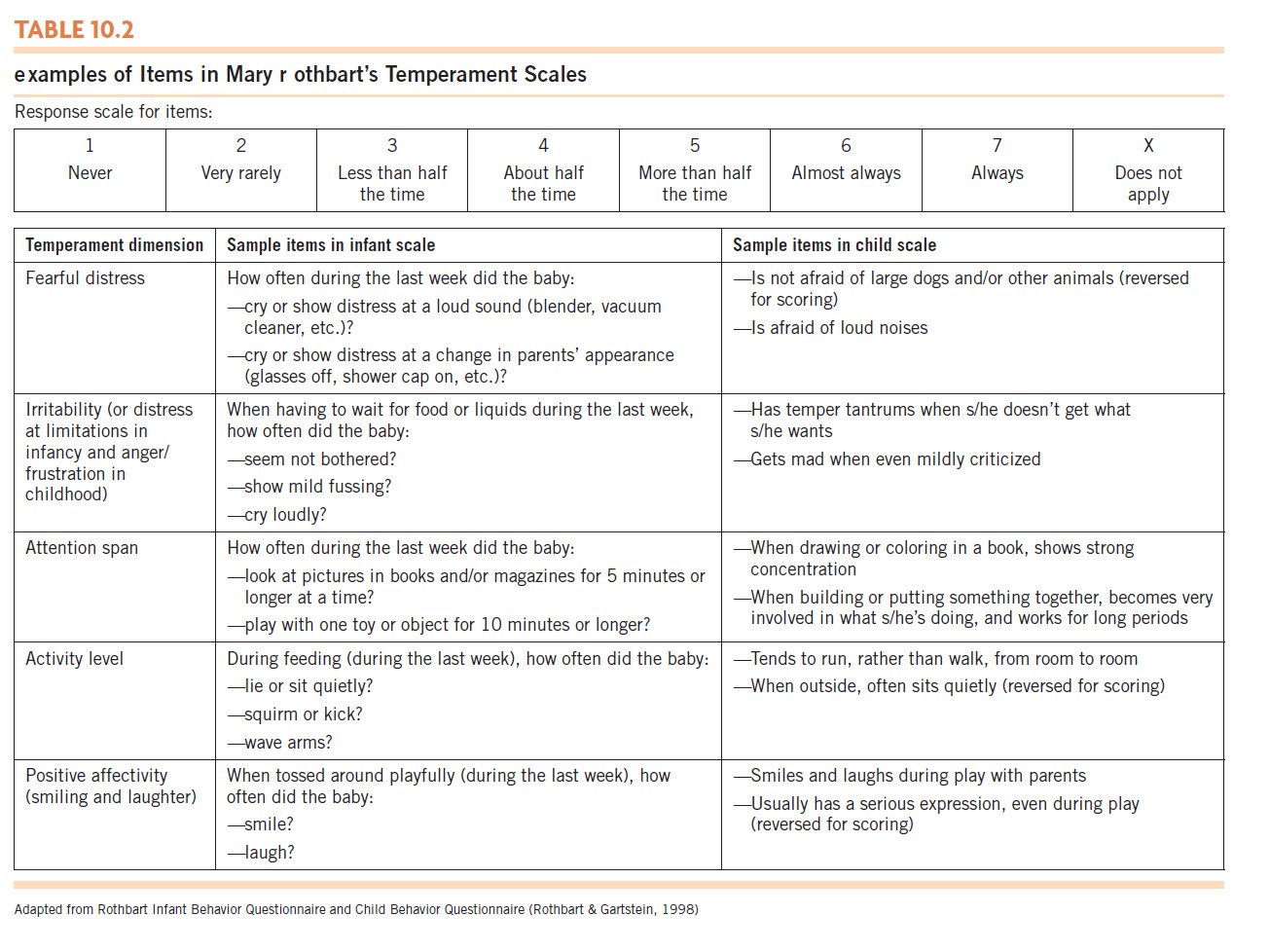

Since the groundbreaking efforts of Thomas and Chess, researchers have devoted a great deal of effort to refining both the definition of temperament and its measurement (see Box 10.2). Unlike Thomas and Chess, many contemporary researchers differentiate among types of negative emotionality and assess different types of regulatory capacities. More recent research suggests that infant temperament is captured by six dimensions (Rothbart & Bates, 1998, 2006):

- Fearful distress/inhibition—distress and withdrawal, and their duration, in new situations

- Irritable distress—fussiness, anger, and frustration, especially if the child is not allowed to do what he or she wants to do

- Attention span and persistence—duration of orienting toward objects or events of interest

- Activity level—how much an infant moves (e.g., waves arms, kicks, crawls)

- Positive affect/approach—smiling and laughing, approach to people, degree of cooperativeness and manageability

- Rhythmicity—the regularity and predictability of the child’s bodily functions such as eating and sleeping

The terms used by investigators to refer to these dimensions vary somewhat—for example, “irritable distress” may be called “frustration” or “anger”—but these dimensions generally include most of the aspects of temperament that have been studied extensively.

In childhood, the first five of these dimensions (see Table 10.2) are particularly important in classifying children’s temperament and predicting their behavior (Rothbart & Bates, 1998). In addition, there is some evidence that a dimension referred to as agreeableness/adaptability may be another important aspect of temperament (Knafo & Israel, 2012; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Agreeableness involves exhibiting positive emotions and behaviors toward others (e.g., getting along with others and caring about them versus being aggressive and manipulative), as well as the tendency to affiliate with others. Adaptability involves being able to adjust to specific conditions, including the needs and desires of others.

405

406

Box 10.2: a closer look

MEASUREMENT OF TEMPERAMENT

Currently, a number of different methods are used to assess temperament. In one method, similar to that used by Thomas and Chess, parents or other adults (usually teachers or observers) report on aspects of a child’s temperament, such as fearfulness, anger/frustration, and positive affect. These reports, based on adults’ observations of the children in various contexts (see Table 10.2), tend to be fairly stable over time and predict general later development in such areas as behavioral problems, anxiety disorders, and social competence (A. Berger, 2011; Rothbart, 2011; Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

Laboratory observations have also been used to assess aspects of temperament such as behavioral inhibition, emotionality, and regulatory capacities. In a longitudinal study conducted by Jerome Kagan and his colleagues, for example, the investigators observed children’s reactions to a variety of novel experiences in early infancy, at age 2, and at age 4½. Across all three ages, about 20% of the children were consistently quite inhibited and reactive when exposed to the unfamiliar stimuli. As infants, they cried and thrashed about when brightly colored toys were moved back and forth in front of their faces or when a cotton swab dipped in dilute alcohol was applied to their nose. At age 2, one-third of these inhibited children were highly fearful in unfamiliar laboratory situations—such as being exposed to a loud noise, the smell of alcohol, and an unfamiliar woman dressed in a clown outfit—and nearly all showed at least some fear in these situations. Other children were less reactive: as infants, they rarely fussed when they en-countered the novel experiences, and at age 2, two-thirds showed little or no fear in the unfamiliar situations.

At the age of 4½, the children who had been reactive to unfamiliar situations were more subdued, less social, and less positive in their behavior than were the uninhibited children, who were relatively spontaneous, asked questions of the researchers when being evaluated, commented on events happening around them, and smiled and laughed more (Kagan, 1997; Kagan & Fox, 2006; Kagan, Snidman, & Arcus, 1998). Even in adolescence, individuals who were inhibited as children exhibited some evidence of heightened worrying and unease with strangers (Kagan, 2012). Thus, laboratory observations appear to be good measures of behavioral inhibition.

Physiological measures also have proved useful for assessing some aspects of children’s temperament. For example, researchers have found that high-reactive and low-reactive children exhibit differences in the variability of their heart rate (Kagan, 1998; Kagan & Fox, 2006). Heart-rate variability—how much an individual’s heart rate normally fluctuates—is believed to reflect, in part, the way the central nervous system responds to novel situations and the individual’s ability to regulate emotion (Porges, 2007; Porges, Doussard-Roosevelt, & Maiti, 1994). Investigators often measure this fluctuation of heart rate in terms of vagal tone, an index of how effectively the vagus nerve—which regulates autonomic nervous system functioning— modulates heart rate in respiratory inhalation and exhalation (inhalation suppresses vagal tone, increasing heart rate; exhalation restores vagal tone, decreasing heart rate). Children who have heart rates that are constantly high and that vary little as a function of breathing are said to have low vagal tone. These children tend to be negatively reactive and inhibited in response to novel situations.

In contrast, children who have variable and often lower heart rates are said to have high vagal tone. After the first year of life, these children tend to exhibit positive emotions and few negative reactions in novel or even stressful situations, such as when dealing with a new preschool. Vagal tone after infancy has been linked with levels of interest and attention, as well as with levels of positive expressiveness (Beauchaine, 2001; Calkins & Swingler, 2012; R. Feldman, 2009; Fox & Field, 1989; Oveis et al, 2009).

A vital component of emotion regulation is the modulation of vagal tone in challenging situations that require an organized response (Porges, 2007). This modulation involves autonomic physiological processes, referred to as vagal suppression, that allow the child to shift away from the physiological responses triggered by the situation and to focus on processing information relevant to the situation and generating coping strategies. Vagal suppression also allows for higher physiological arousal that can be used to deal with the situation at hand.

Vagal suppression during challenging situations has been related to a variety of positive outcomes over the course of childhood, including better regulation of state and more attentional control in infancy (Huffman et al., 1998); fewer behavior problems, higher status with peers, and more appropriate emotion regulation in the preschool years (Calkins & Dedmon, 2000; Calkins & Keane, 2004); and sustained attention in the school years (Suess, Porges, & Plude, 1994; see also R. A. Thompson, Lewis, & Calkins, 2008). In addition, children with higher vagal tone in general or greater vagal suppression during challenges appear less likely to have problem behaviors and anxiety if exposed to stressors such as conflict between their parents (El-Sheikh, Harger, & Whitson, 2001; El-Sheikh & Whitson, 2006), especially if they live in environments that other-wise are not especially high in stress and risk (Obradović et al., 2010). Findings such as these support the idea that vagal tone and its suppression assess some capacity related to adaptation and emotion regulation.

Another commonly used physiological measure of temperament is electroencephalographic recordings (see Chapter 3) of frontal-lobe activity. Activation of the left frontal lobe of the cortex as measured with an electroencephalogram (EEG) has been associated with approach behavior, positive affect, exploration, and sociability. In contrast, activation of the right frontal lobe has been linked to withdrawal, a state of uncertainty, fear, and anxiety (Kagan & Fox, 2006). Thus, when confronted with novel stimuli, situations, or challenges, infants and children who show greater right frontal activation on the EEG are more likely to react with anxiety and avoidance (Calkins, Fox, & Marshall, 1996; Kagan & Fox, 2006), whereas individuals who show left frontal activation are more likely to exhibit a relaxed, often happy mood and an eagerness to engage new experiences or challenges (Kagan & Fox, 2006; L. K. White et al., 2012). EEG activation patterns are associated with children’s ongoing temperament, not just with their reactions in these specific situations. For example, compared with uninhibited peers, inhibited preschoolers showed greater activation in the right frontal area even under resting conditions, and children who were inhibited as 2-year-olds exhibited greater right than left hemisphere activation at age 11 (Kagan et al., 2007).

A third physiological measure of temperament is cortisol level. In reaction to stress, the adrenal cortex secretes steroid hormones, including cortisol, which, as noted previously, helps to activate energy reserves (C. S. Carter, 1986). Sometimes individual differences in children’s cortisol baseline—that is, their typical cortisol level—have been related to levels of internalizing problems such as inhibition, anxiety, and social withdrawal (Granger et al., 1994; Smider et al., 2002), and to regulation (Gunnar et al., 2003) and the acting out of behavioral problems (Gunnar & Vazquez, 2006; Shirtcliff et al., 2005; Shoal, Giancola, & Kirillova, 2003). For example, 2-year-olds who, in a mildly threatening situation, exhibit extremely fearful reactions—such as freezing up in their behavior—tend to have higher levels of cortisol in general, not just in such situations (K. A. Buss et al., 2004).

In addition, cortisol reactivity—the amount of cortisol produced in a given situation—has been linked to temperament differences in emotionality, inhibition, regulation, and maladjustment (Ashman et al., 2002; C. Blair et al., 2008; Granger et al., 1998). For instance, in child-care settings, children high in temperamental negative emotionality and low in regulation show larger increases in cortisol levels than do other children (Dettling et al., 2000). Cortisol reactivity is related to internalizing problems such as anxiety primarily if a child displays a heightened response to a familiar stressor (Gunnar & Vazquez, 2006).

When attempting to find links between children’s cortisol levels and aspects of their temperament, it is important to consider the children’s experience in a particular context. This was highlighted in a study by Gunnar (1994), which compared the cortisol levels of two groups of children—outgoing and active versus anxious and withdrawn—in their first year of group care. At the start of the school year, the active and outgoing children showed higher cortisol levels; later in the school year, however, the reverse was true. According to teachers’ reports at the time of the second cortisol testing, the former group was higher in popularity and had fewer problems interacting socially. Presumably, the less inhibited children had actively dealt with the new situation, initially exposing themselves to stress and raising their cortisol levels but subsequently adapting successfully. The inhibited children, in contrast, had avoided the challenges (and stress) of the new situation and were still not well adjusted to it (Gunnar, 1994).

One exception was uninhibited children who were also unregulated; they exhibited relatively high cortisol levels at preschool even later in the year, perhaps because their impulsive behavior led to peer rejection (Gunnar et al., 2003). Another exception tends to be for exuberant children who are less socially integrated (Tarullo et al., 2011); they tend to maintain higher levels of cortisol over the school year, perhaps because they are often dealing with stressful social interactions.

Each type of measure of temperament has advantages and disadvantages, and there is considerable debate regarding the merits of the various methods (Kagan, 1998; Kagan & Fox, 2006; Rothbart & Bates, 1998, 2006). The key advantage of parents’ reports of temperament is that parents have extensive knowledge of their children’s behavior in many different situations. One important disadvantage of this method is that parents may not always be objective in their observations, as suggested by the fact that their reports sometimes do not correspond with what is found with laboratory measures (Seifer et al., 1994). Another disadvantage is that many parents do not have wide knowledge of other children’s behavior to use as a basis for comparison when reporting on their own children (what is irritability to some parents, for example, may be near-placidness to others).

The key advantage of laboratory observational data is that such data are less likely to be biased than is an adult’s personal view of the child. A key disadvantage is that children’s behavior usually is observed in only a limited set of circumstances. Consequently, laboratory observational measures may reflect a child’s mood or behavior at a given moment, in a particular context, rather than reflecting the child’s general temperament.

Physiological measures such as an EEG and vagal tone are also relatively objective and unlikely to be biased, but there is no way to tell whether the processes reflected by physiological measures are a cause or consequence of the child’s emotion and behavior in the specific situation. It is unclear, for example, whether left and right frontal lobe activity triggers, or is triggered by, a particular emotional response. Thus, no measure of temperament is foolproof, and it is prudent to assess temperament with a variety of different methods.

407

408

Stability of Temperament over Time

As you have seen, temperament, by definition, involves traits that remain fairly stable over time and, in some cases, seem to increase in stability with age (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000). One example of trait stability comes from research indicating that children who exhibited inhibition or fearful distress when presented with novel stimuli as infants also were prone to exhibit elevated levels of fear in novel situations at age 2 and elevated levels of social inhibition at age 4½. Similarly, children who are more prone to negative emotion than their peers at age 3 tend to be more emotionally negative than their peers at ages 6 and 8 (Guerin & Gottfried, 1994; Rothbart, Derryberry, & Hershey, 2000), and, across the same age range, those prone to positive affect remain relatively positive (Durbin et al. 2007; Sallquist et al., 2009).

Research further indicates that children who are high in the ability to focus attention in the preschool years are high in this ability in early adolescence (B. C. Murphy et al., 1999) and that there is also stability in attentional and behavioral regulation from childhood into adolescence (N. Eisenberg, Hofer et al., 2008) and across adolescence (Ganiban et al., 2008). As noted, some aspects of temperament tend to be more stable than others. For example, over the course of infancy, positive emotionality, fear, and distress/anger activity level may be more stable than activity level (Lemery et al., 1999).

The Role of Temperament in Children’s Social Skills and Maladjustment

One of the reasons for researchers’ deep interest in temperament is that it plays an important role in determining children’s social adjustment. Consider a boy who is prone to anger and has difficulty controlling this emotion. Compared with other boys, he is likely to sulk, to yell at others, and to be defiant with adults and aggressive with peers. Such behaviors often lead to long-term adjustment problems. Consequently, it is not surprising that differences in aspects of temperament such as anger/irritability, positive emotion, and the ability to inhibit behavior—aspects reflected in the difference between difficult and easy temperament—have been associated with differences in children’s social competence and maladjustment (Coplan & Bullock, 2012; Eiden et al., 2009; N. Eisenberg et al., 2010; Kagan, 2012; Kochanska et al., 2008).

Such differences are highlighted by a large longitudinal study conducted in New Zealand by Caspi and colleagues. These researchers found that participants who were negative and unregulated as young children tended as adolescents or young adults to have more problems with adjustment, such as not getting along with others, than did peers with different temperaments. They were also more likely to engage in illegal behaviors and to get in trouble with the law (Caspi et al., 1995; Caspi & Silva, 1995; B. Henry et al., 1996). At age 21, they reported getting along less well with whomever they were sharing living quarters (e.g., roommates) and reported being unemployed more often. They also tended to have few people from whom they could get social support (Caspi, 2000) and were prone to negative emotions like anxiety (Caspi et al., 2003). At age 32, they had poorer physical health and personal resources, greater substance dependence, more criminal offenses, and more problems with gambling (Moffitt et al., 2011; Slutske et al., 2012).

409

It is important to note, however, that aspects of temperament like negative emotionality may not always be associated with children’s negative outcomes such as having problem behaviors and poor social relationships. It seems that some children with certain temperamental characteristics are especially sensitive to their social environments, whether positive or negative. There is some evidence, for example, that, in highly stressful social environments (i.e., poverty, exposure to harsh parenting), children who are prone to negative emotions tend to do worse than children who are not, but that, in supportive social environments, they often tend to do better than their more emotionally positive peers (Belsky & Pluess, 2009). Evolutionarily oriented theorists argue that this “for better or for worse” pattern of findings, labeled differential susceptibility, occurs because aspects of temperament and behavior that are adaptive for survival vary across positive and negative social contexts (B. J. Ellis et al., 2011). For instance, in harsh environments, expressing negative emotion may help children to obtain attention and vital resources needed for survival (even though the negative emotion often results in negative social consequences over time), whereas in supportive environments, proneness to negative emotions might make children more sensitive to parents’ attempts to socialize positive behaviors, which may lead to higher social and moral competence (Kochanska, 1997a).

behavioral inhibition  a temperamentally based style of responding characterized by the tendency to be particularly fearful and restrained when dealing with novel or stressful situations

a temperamentally based style of responding characterized by the tendency to be particularly fearful and restrained when dealing with novel or stressful situations

Researchers also have found stability with regard to behavioral inhibition, the tendency to be high in fearful distress and restrained when dealing with novel or stressful situations. Children who are behaviorally inhibited are more likely than other children to have problems such as anxiety, depression, phobias, and social withdrawal at older ages (Biederman et al., 1990; Fox & Pine, 2012; Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2007; Moffitt et al., 2007). Thus, different problems with adjustment seem to be associated with different temperaments.

goodness of fit  the degree to which an individual’s temperament is compatible with the demands and expectations of his or her social environment

the degree to which an individual’s temperament is compatible with the demands and expectations of his or her social environment

However, how children ultimately adjust depends not only on their temperament but also on how well their temperament fits with the particular environment they are in—what is often called goodness of fit. On the basis of their data, Chess and Thomas (1990) argued, for example, that children with difficult temperaments have better adjustment if they receive parenting that is supportive and consistent rather than punitive, rejecting, or inconsistent. In support of their argument, research indicates that children who are impulsive or low in self-regulation seem to have more problems and are less sympathetic to others if exposed to hostile, intrusive, and/or negative parenting rather than to supportive parenting (Hastings & De, 2008; Kiff et al., 2011; Lengua et al., 2008; Valiente et al., 2004; see also Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Similarly, children prone to negative emotions such as anger are more likely to have behavioral problems such as aggression if exposed to hostile parenting or low levels of positive parenting (Calkins, 2002; Lengua, 2008; Mesman et al., 2009; Morris et al., 2002; see also Bates et al., 2012, for a review). Thus, children exposed to suboptimal parenting do worse if they have unregulated or reactive temperaments.

Not only are children’s maladjustment and social competence predicted by the combination of their temperament and their parents’ child-rearing practices, but the child’s temperament and parents’ socialization efforts also seem to affect each other over time (Belsky et al., 2007; N. Eisenberg et al., 1999; K. J. Kim et al., 2001; E. H. Lee et al., 2013). For example, parents of negative, unregulated children may eventually become less patient and more punitive with their children; in turn, this intensification of disciplining may cause their children to become even more negative and unregulated. Thus, temperament plays a role in the development of children’s social and psychological adjustment, but that role is complex and varies as a function of the child’s social environment and the degree to which a child represents a challenge to the parent (Ganiban et al., 2011).

410

review:

Temperament refers to individual differences in various aspects of children’s emotional reactivity, regulation, and other characteristics such as behavioral inhibition and activity level. Temperament is believed to have a constitutional (biological) basis, but it is also affected by experiences in the environment, including social interactions. Temperament tends to be somewhat stable over time, although the degree of its stability varies across the dimensions of temperament and individuals.

Temperament plays an important role in adjustment and maladjustment. A difficult and unmanageable temperament in childhood tends to predict problem behaviors and low social competence in childhood and adulthood, and children who as infants are fearful and negatively reactive to novel objects, places, and people sometimes have later difficulties in interactions with others, including peers. However, children whose temperaments put them at risk for poor adjustment often do well if they receive sensitive and appropriate parenting and if there is a good fit between their temperament and their social environment.