Peers in Groups

Most children usually have one or a few very close friends and some less close additional friends with whom they spend time and share activities. These groups tend to exist within a larger social network of peers that hangs together loosely. Developmentalists have been especially interested in how these peer groups emerge and change with age and how they affect the development of their members.

The Nature of Young Children’s Groups

When in a setting with a number of their peers, very young children, including toddlers, sometimes interact in small groups. One striking feature of these first peer groups is the early emergence of status patterns within them, with some children being more dominant and central to group activities than are others (Rubin et al., 2006). By the time children are preschool age, there is a clear dominance hierarchy among the members of a peer group. Certain children are likely to prevail over other group members when there is conflict, and there is a consistent pattern of winners and losers in physical confrontations.

As we will discuss shortly, by middle childhood, status in the peer groups involves much more than dominance, and children become very concerned about their peer-group standing. Before examining peer status, however, we need to consider the nature of social groups in middle childhood and early adolescence.

526

Cliques and Social Networks in Middle Childhood and Early Adolescence

cliques  friendship groups that children voluntarily form or join themselves

friendship groups that children voluntarily form or join themselves

Starting in middle childhood, most children are part of a clique. Cliques are friendship groups that children voluntarily form or join themselves. In middle childhood, clique members are usually of the same sex and race and typically number between 3 and 10 (X. Chen, Chang, & He, 2003; Kwon, Lease, & Hoffman, 2012; Neal, 2010; Rubin et al., 2006). Boys’ groups tend to be larger than those of girls (Benenson, Morganstein, & Roy, 1998), although this difference decreases with age (Neal, 2010). By age 11, many of children’s social interactions—from gatherings in the school lunchroom to outings at the mall—occur within the clique (Crockett, Losoff, & Peterson, 1984). Although friends tend to be members of the same clique, many members of a clique do not view each other as close friends (Cairns et al., 1995).

A key feature that underlies cliques and binds their members together is the similarities the members share. Like friends, members of cliques tend to be similar in their degree of academic motivation (Kindermann, 2007; Kiuru et al., 2009); in their aggressiveness and bullying; and in their shyness, attractiveness, popularity, and adherence to conventional values such as politeness and cooperativeness (Espelage, Holt, & Henkel, 2003; Kiesner, Poulin, & Nicotra, 2003; Leung, 1996; Salmivalli & Voeten, 2004; Witvliet et al., 2010). Not only do like individuals tend to group together in cliques, but membership in a clique also seems to increase the likelihood that children will exhibit behaviors similar to those of other group members (Espelage et al., 2003).

Despite the social glue of similarity, the membership of cliques tends to be relatively unstable (Cairns et al., 1995). A study of 4th- and 5th-graders, for example, found the turnover rate of cliques to be about 50% over 8 months (Kindermann, 1993); and in a study of 6th-graders, only about 60% of the members of cliques maintained their group ties over the school year (Kindermann, 2007). The degree to which cliques remain stable appears to depend in large part on whether children are assigned to the same classroom from one year to the next (Neckerman, 1996).

In contrast to the tendency of dominant children to be the central figures in young children’s groups, during the school years, girls and boys who are central to the peer group are likely to be popular, athletic, cooperative, seen as leaders, and studious relative to other peers (Farmer & Rodkin, 1996). However, especially in the case of boys, and more especially in the case of aggressive groups of youths, the central figures are sometimes domineering, aggressive, and viewed by peers as “tough” or “cool” (Estell et al., 2002; Rodkin et al., 2006).

Cliques in middle childhood serve a variety of functions: they provide a ready-made pool of peers for socializing; they offer validation of the characteristics that the group members have in common; and, perhaps most important, they provide a sense of belonging. By middle childhood, children are quite concerned about being accepted by peers, and issues of peer status become a common topic of children’s conversation and gossip (Gottman, 1986; Kanner et al., 1987; Rubin et al., 1998). Being accepted by others who are similar to oneself in various ways may provide a sense of personal affirmation, as well as of being a welcomed member of the larger peer group.

Cliques and Social Networks in Adolescence

From ages 11 to 18, there is a marked drop in the number of students who belong to a single clique and an increase in the number of adolescents who have ties to many cliques or to students at the margins of cliques (Shrum & Cheek, 1987). In addition, membership in a clique is fairly stable across the school year by 10th grade (Değirmencioğlu et al., 1998).

527

Although cliques at younger ages contain mostly same-sex members, by 7th grade, about 10% of cliques contain both boys and girls (Cairns et al., 1995). Thereafter, dyadic dating relationships become increasingly common (Dunphy, 1963; Richards et al., 1998); thus, by high school, cliques of friends often include adolescents of both genders (J. L. Fischer, Sollie, & Morrow, 1986; La Greca, Prinstein, & Fetter, 2001).

The dynamics of cliques also vary at different ages in adolescence. During early and middle adolescence, children report placing a high value on being in a popular group and in conforming to the group’s norms regarding dress and behavior. Failure to conform—even something as trivial-seeming as wearing the wrong brand or style of jeans or belonging to an afterschool club that is viewed as uncool—can result in being ridiculed or shunned by the group. In comparison with older adolescents, younger adolescents also report more interpersonal conflict with members of their group as well as with members of other groups. In later adolescence, the importance of belonging to a clique and of conforming to its norms appears to decline, which may account for the decline in friction and antagonism within and between groups. With increasing age, adolescents not only are more autonomous but they also tend to look more to individual relationships than to group relationships to fulfill their social needs (Gavin & Furman, 1989; Rubin et al., 1998).

crowds  groups of adolescents who have similar stereotyped reputations; among American high school students, typical crowds may include the “brains,” “jocks,” “loners,” “burnouts,” “punks,” “populars,” “elites,” “freaks,” or “nonconformists”

groups of adolescents who have similar stereotyped reputations; among American high school students, typical crowds may include the “brains,” “jocks,” “loners,” “burnouts,” “punks,” “populars,” “elites,” “freaks,” or “nonconformists”

Although older adolescents seem less tied to cliques, they still often belong to crowds. Crowds are groups of people who have similar stereotyped reputations. Among high school students, typical crowds may include the “brains,” “jocks,” “loners,” “burnouts,” “punks,” “populars,” “elites,” “freaks,” “hip-hoppers,” “geeks,” “normals,” and “metalheads” (B. B. Brown & Klute, 2003; Delsing et al., 2007; Doornwaard et al., 2012; La Greca et al., 2001). Which crowd adolescents belong to is often not their choice; crowd “membership” is frequently assigned to the individual by the consensus of the peer group, even though the individual may actually spend little time with other members of that designated crowd (B. B. Brown, 1990).

Being associated with a crowd may enhance or hurt adolescents’ reputations and influence how they are treated by peers. Someone labeled a freak, for example, may be ignored or ridiculed by people in groups such as the jocks or the populars (S. S. Horn, 2003). Thus, it is not surprising that youths in high-status groups tend to have higher self-esteem than do youths in less desirable crowds (B. B. Brown, Bank, & Steinberg, 2008). Being labeled as part of a particular crowd also may limit adolescents’ options with regard to exploring their identities (see Chapter 11). This is because crowd membership may “channel” adolescents into relationships with other members of the same crowd rather than with a diverse group of peers (B. B. Brown, 2004; Eckert, 1989). Adolescents in one crowd, for instance, might be exposed to their peers’ acceptance of violence or drug use, whereas members of another crowd may find that their peers value success in academics or sports (La Greca et al., 2001).

An example of the potential consequences of such channeling comes from a large study in Holland that found that adolescents’ persistent identification with nonconventional crowds (e.g., hip-hoppers, nonconformists, and metalheads) was associated with more consistent problem behaviors throughout adolescence, whereas adolescents’ consistent identification with conventional groups was generally associated with less problematic behavior (Doornwaard et al., 2012). Thus, experiences in a crowd, like interactions with friends, may help shape youths’ behavior.

528

A relatively new dimension in which peers interact, one that they have used with increasing frequency in recent years, is cyberspace. As Box 13.2 explains, youths’ most frequent form of contact with friends and peers is now digital communication, and the role and effects, both positive and negative, of this venue have become subjects of considerable debate.

Negative Influences of Cliques and Social Networks

Like close friends, members of the clique or the larger peer network can sometimes lead the child or adolescent astray. Preadolescents and adolescents are more likely to goof off in school, smoke, drink, use drugs, or engage in violence, for example, if members of their peer group do so and if they hang out with peers who have been in trouble (Lacourse et al., 2003; Loukas et al., 2008). Adolescents who have an extreme orientation to peers—that is, who are willing to do anything to be liked by peers—are particularly at risk for such behaviors if engaging in them secures peer acceptance (Fuligni et al., 2001). Adolescents who are low in self-regulation are also at increased risk if their peers are antisocial (T. W. Gardner, Dishion, & Connell, 2008).

gang  a loosely organized group of adolescents or young adults who identify as a group and often engage in illegal activities

a loosely organized group of adolescents or young adults who identify as a group and often engage in illegal activities

Perhaps the greatest potential for negative peer-group influence comes with membership in a gang, which is a loosely organized group of adolescents or young adults who identify as a group and often engage in illegal activities. Gang members often say that they join or stay in a gang for protection from other gangs. One male gang member explained that “being cool with a gang” meant that “you don’t have to worry about nobody jumping you. You don’t got to worry about getting beat up” (quoted in Decker, 1996, p. 253).

Gangs also provide members with a sense of belonging and a way to spend their time. Gang members frequently report that the most common gang activities are “hanging out” together and engaging in fairly innocuous behaviors (e.g., drinking beer, playing sports, cruising, looking for girls, and having parties) (Decker & van Winkle, 1996). Nonetheless, adolescents tend to engage in more illegal activities such as delinquency and drug abuse when they are in a gang than when they are not (Alleyne & Wood, 2010; Bjerregaard & Smith, 1993; Craig et al., 2002; Esbensen & Huizinga, 1993; see Chapter 14), and the heightened risk for such activities seems to be due to both pre-existing characteristics of the adolescents who join gangs and their experience of being in a gang (Barnes, Beaver, & Miller, 2010; Delisi et al., 2009).

The potential for peer-group influence to promote problem behavior is affected by family and cultural influences. As noted in our discussion of friendship, having authoritative, involved parents helps protect adolescents from peer pressure to use drugs, whereas having authoritarian, detached parents increases adolescents’ susceptibility to such pressure. Correspondingly, youths who have poor relationships with their mothers may be especially vulnerable to pressure from the peer group (Farrell & White, 1998).

At the same time, the strength of peer influence on problem behavior can vary by culture and subculture. For example, compared with its strength among European American adolescents, peer influence on the use of drugs, drinking, aggression, or school misconduct appears to be weaker for Native American youths who live on a reservation and for adolescents in mainland China or Taiwan (C. Chen et al., 1998; Swaim et al., 1993), perhaps because family sanctions against such behaviors play a more important role in these groups. Although the precise reasons for all these differences in peer-group influence are not yet known, it is clear from findings such as these that family and cultural factors can affect the degree to which peers’ behaviors are associated with adolescents’ problem behavior.

529

Box 13.2: a closer look

CYBERSPACE AND CHILDREN’S PEER EXPERIENCE

Technology such as online social media, instant messaging, and phone texting are playing an increasing role in peer interactions of children and especially of adolescents. According to a report on the 2009 online activities of U.S. adolescents aged 12 to 17, 73% used social network sites, 67% used instant messaging, 78% played online games, and 49% read blogs (Zickuhr, 2010). Almost three-fourths of online adolescents and adults in their mid-20s or younger had joined a social networking site such as MySpace or Facebook, where they created a descriptive personal profile and built a network with other users (Lenhart et al., 2010).

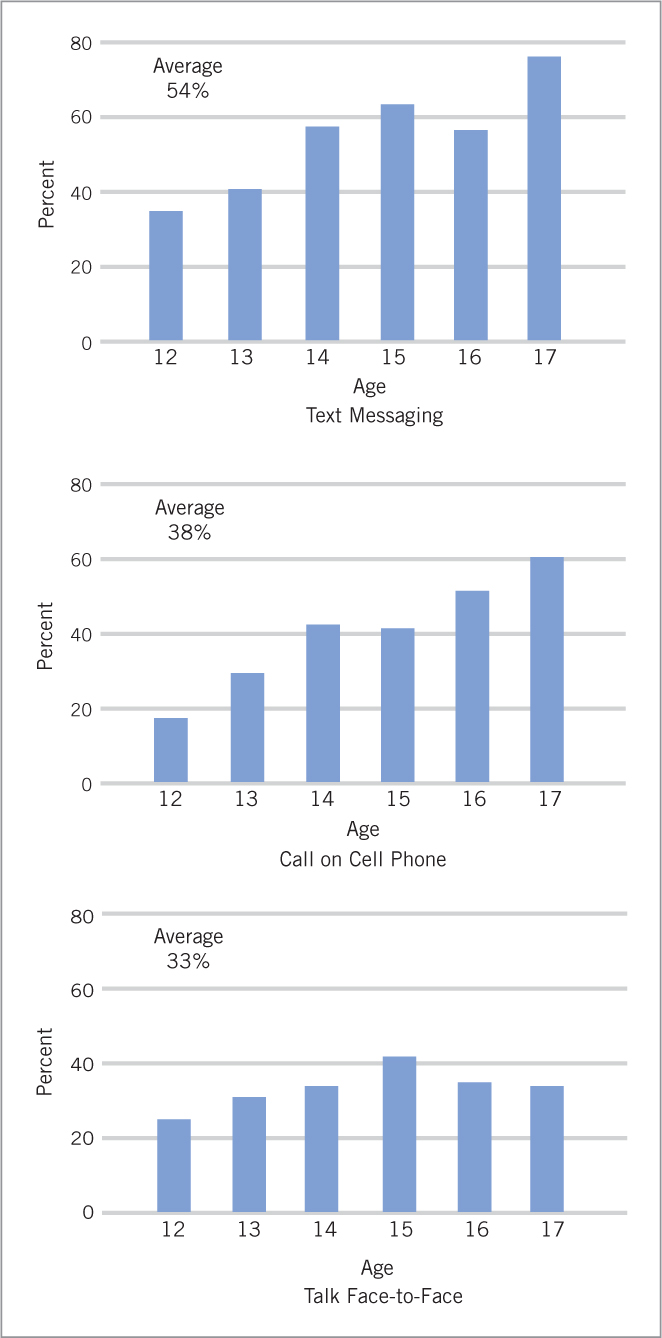

In addition, a report on U.S. adolescents’ cell phone use in 2009 indicated that approximately 75% of 12- to 17-year-olds owned their own cell phones and that 72% of all adolescents engaged in text messaging. The frequency of texting was high: a large survey in four cities showed that 54% of teens between the ages of 12 and 17 texted friends daily, with about half of these teens sending 50 or more text messages a day and one-third sending more than 100 texts a day (Lenhart et al., 2010).

Given youths’ tremendous use of digital technologies for their social interactions, social and behavioral scientists, as well as parents, have expressed considerable concern about the effects that these modes of communication may have on children’s and adolescents’ social development—and especially on their social relationships. Two major perspectives have guided research on this issue. One view is the rich-get-richer hypothesis, which proposes that those youths who already have good social skills benefit from the Internet and related forms of technology when it comes to developing friendships (Peter, Valkenburg, & Schouten, 2005). In contrast, according to the social- compensation hypothesis, social media may be especially beneficial for lonely, depressed, and socially anxious adolescents. Specifically, because they can take their time thinking about, and revising, what they say and reveal in their messages, these youths may be more likely to make personal disclosures online than offline, which eventually fosters the formation of new friendships.

In support of the rich-get-richer hypothesis, researchers have found that adolescents who are not socially anxious or lonely use the Internet for communication more often than do adolescents who are (Valkenburg & Peter, 2007b; Van den Eijnden et al., 2008). Moreover, youths who were better adjusted at age 13 to 14 were found to use social networking more at ages 20 to 22 and to exhibit a similarity in their online and offline social competence (e.g., in peer relationships, friendship quality, adjustment) (Mikami et al., 2010). Thus, socially competent people may benefit most from the Internet because they are more likely to interact in appropriate and positive ways when engaged in social networking.

However, consistent with the social-compensation hypothesis, lonely and socially anxious youths seem to prefer online communication over face-to-face communication (Peter et al., 2005; Pierce, 2009). There is also evidence that online communication is used by youths with high levels of depressive symptoms to make friends and express their feelings (J. M. Hwang, Cheong, & Feeley, 2009), and that such use is associated with less depression for youths with low-quality best-friend relationships (Selfhout et al., 2009). Thus, the use of online technology often may provide depressed youths or those with low- quality offline friendships a means of obtaining communication and emotional intimacy with peers.

Another issue is how online communication may affect youths’ existing friendships. Some investigators have hypothesized that online communication impairs the quality of existing friendships because it displaces the time that could be spent strengthening the affection and commitment these friendships can provide (Kraut et al., 1998; see Valkenburg & Peter, 2011). Alternatively, other investigators have hypothesized that recent Internet-based communication technologies are designed to facilitate communication among existing friends, allowing them to maintain and enhance the closeness of their relationships (J. A. Bryant, Sanders-Jackson, & Smallwood, 2006; Peter et al., 2005; Valkenburg & Peter, 2011).

Overall, the latter view has received more support (Valkenburg & Peter, 2007a, 2009a, b; Valkenburg & Peter, 2011). In existing friendships, online communication seems to foster self-disclosure, which enhances friendship quality. In fact, many adolescents tend to use social-networking sites to connect with people they know offline and to strengthen these preexisting relationships (Reich, Subrahmanyam, & Espinoza, 2012). Similarly, the use of instant messaging has been associated with an increase in the quality of adolescents’ existing friendships over time (Valkenburg & Peter, 2009b). In contrast, high levels of using the Internet primarily for entertainment (e.g., playing games, surfing) or for communication with strangers can harm the quality of friendships (Blais et al., 2008; Punamäki et al., 2009; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007b) and predicts increases in anxiety and depression (Selfhout et al., 2009).

Another potential risk of online use—one that is quite serious—is cyberbullying among adolescents (Kiriakidis & Kavoura, 2010; Kowalski, Limber, & Agatston, 2008; Tokunaga, 2010). Internet applications can be used by youths to intimidate, insult, and humiliate peers and ensure a much larger group of peer witnesses than is possible in everyday face-to-face interactions. Cyberbullies and cybervictims tend to be the same youths who are bullies or victims offline (Twyman et al., 2010). Cybervictims, like victims offline, tend to be high in social anxiety, psychological distress, and symptoms of depression, as well as to have aggressive tendencies, poor anger management, and problems at school (Valkenburg & Peter, 2011). However, nearly all the relevant research is correlational, so it is not clear if youths with these characteristics elicit cyberbullying, if cyberbullying causes emotional and behavioral problems, or if both factors come into play.

530

Although social media are often used to bully peers, they also may be helpful in countering the effects of peer rejection. In an experimental study, adolescents and young adults played what they were led to believe was an online interactive game with unfamiliar peers (Reijntjes, Thomaes et al., 2011). Actually, the game is a standardized laboratory computer program designed to elicit feelings of social inclusion or exclusion in the only real player—the research participant. In the exclusion version, the program’s “other players” eventually begin to play among themselves, completely ignoring the participant. In this study, after the game ended, the excluded participants showed lower levels of self-esteem and higher levels of anger and shame than did the included participants. Next, the excluded participants spent 12 minutes either playing a computer puzzle game by themselves or engaging in instant messaging with an unfamiliar other-sex person, with whom they were free to discuss anything except the just-completed game.

The researchers found that excluded participants who engaged in the text messaging showed greater recovery from exclusion in terms of self-esteem and negative affect than did the excluded participants who played the puzzle game. These findings are consistent with the previously mentioned benefits of cybercommunication for shy, anxious, or depressed individuals and suggest that Internet relationships can have benefits for children and youths who have difficulties with peer relationships.

531

Romantic Relationships with Peers

In the United States, 25% of 12-year-olds and 70% of 18-year-olds report having had a recent romantic relationship (K. Carver, Joyner, & Udry, 2003). Similar rates have been reported for youth in Europe (Zani, 1991). For adolescents 15 years or younger, two-thirds of these romantic relationships, on average, do not last more than 11 months. For more than half of the older adolescents, they do (Collins, 2003).

The path to heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence typically begins in mixed-gender peer groups, with dating emerging out of mixed-gender affiliations in these groups (Collins & Steinberg, 2006; Connolly et al., 2004). From ages 14 to 18, youth tend to balance the time they spend with romantic partners and with same-gender cliques, gradually decreasing the percent of time they spend in mixed-gender groups (Richards et al., 1998). However, by early adulthood, the time spent with romantic partners increases to the level that it is at the expense of involvement with friends and crowds (Reis et al., 1993). Less is known about the emergence of romantic relationships among sexual-minority youths: although most report some sexual activity in adolescence (Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000), whether they date depends on the level of acceptance in their social environment (L. M. Diamond, Savin-Williams, & Dube, 1999).

Young adolescents tend to be drawn to, and choose, partners on the basis of characteristics that bring status—such as being stylish and having the approval of peers (Pellegrini & Long, 2007). By middle to late adolescence, traits such as kindness, honesty, intelligence, and interpersonal skills are also important factors in selecting a romantic partner (Ha et al., 2010; Regan & Joshi, 2003). Older adolescents are more likely than younger ones to select partners based on compatibility and characteristics that enhance intimacy, such as caring and compromise (Collins, 2003).

For many adolescents, being in a romantic relationship is important for a sense of belonging and status in the peer group (W. Carlson & Rose, 2007; Connolly et al., 1999). By late adolescence, having a high-quality romantic relationship is also associated with feelings of self-worth and a general sense of competence (Collins, Welsh, & Furman, 2009; Connolly & Konarski, 1994), and it can improve functioning in adolescents who are prone to depression, sadness, or aggression (V. A. Simon, Aikins, & Prinstein, 2008).

However, romantic relationships can also have negative effects on development. Early dating and sexual activity, for example, are associated with increased rates of current and later problem behaviors, such as drinking and using drugs, as well as with social and emotional difficulties (e.g., Davies & Windle, 2000; Zimmer-Gembeck, Siebenbruner, & Collins, 2001). This is especially true if the romantic partner is prone to delinquent behavior (Lonardo et al., 2009; S. Miller et al., 2009). When a romantic relationship doesn’t work out, hurt feelings for one or both partners are par for the course, but girls who are treated badly or are rejected in a relationship seem particularly prone to depression and anxiety (W. E. Ellis, Crooks, & Wolfe, 2009).

532

The quality of adolescents’ romantic relationships appears to mirror the quality of their other relationships. Adolescents who have had poor-quality relationships with parents and peers are likely to have romantic relationships characterized by low levels of intimacy and commitment (Ha et al., 2010; Oriña et al., 2011; Seiffge-Krenke, Overbeek, & Vermulst, 2010) and by aggression (Stocker & Richmond, 2007; Zimmer-Gembeck, Siebenbruner, & Collins, 2004).

It is also believed that adolescents’ working models of relationships with their parents tend to be reflected in their romantic relationships. This belief is supported by the finding that children who were securely attached at age 12 months were more socially competent in elementary school, which predicted more secure relationships with friends at age 16. The security of these friendships, in turn, predicted more positive daily emotional experiences in romantic relationships at ages 20 to 23 and less negative affect in conflict resolution and collaborative tasks with romantic partners (J. A. Simpson et al., 2007). Related research suggests that individuals who were securely attached in infancy, in contrast to those with insecure attachments, rebound better from conflicts with their romantic partners in early adulthood (Salvatore et al., 2011). Thus, romantic relationships appear to be affected in multiple ways by youths’ history of relationships with parents and peers (Rauer et al., 2013).

review:

Very young children often interact with peers in groups, and dominance hierarchies emerge in these groups by preschool age. By middle childhood, most children belong to cliques of same-gender peers who often are similar in their aggressiveness and orientation toward school.

In adolescence, the importance of cliques tends to diminish, and adolescents typically belong to more than one group. The degree of conformity to the norms of the peer group regarding dress, talk, and behavior decreases over the high school years. Nonetheless, adolescents often are members of crowds, such as the jocks or brains—that is, groups of people with similar reputations. Even though adolescents often do not choose what crowd they belong to, belonging to a particular crowd may affect their reputations, their treatment by peers, and their exploration of identities.

Peer groups sometimes contribute to the development of antisocial behavior and the use of alcohol and drugs, although children and adolescents may also select peers with problem behaviors that are similar to their own. Membership in a gang is particularly likely to encourage problem behavior. The degree to which the peer group influences adolescents’ antisocial behavior or drug abuse appears to vary according to family and cultural factors.

Involvement in romantic relationships increases with age in adolescence, and youths increasingly select partners based on intimacy, compatibility, and caring rather than on criteria such as social status and stylishness. Involvement in romantic relationships often is related to a sense of belonging, high self-esteem, and reduced depressive feelings, but can also lead to involvement in risky behaviors, such as drinking and using drugs, and to feelings of rejection if one partner treats the other poorly. The quality of youths’ romantic relationships tends to mirror the quality of their relationships with parents and friends.