552

Moral Development

553

- Moral Judgment

- Piaget’s Theory of Moral Judgment

- Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Judgment

- Prosocial Moral Judgment

- Domains of Social Judgment

- Review

- The Early Development of Conscience

- Factors Affecting the Development of Conscience

- Review

- Prosocial Behavior

- The Development of Prosocial Behavior

- The Origins of Individual Differences in Prosocial Behavior

- Box 14.1: A Closer Look Cultural Contributions to Children’s Prosocial and Antisocial Tendencies

- Box 14.2: Applications School-Based Interventions for Promoting Prosocial Behavior

- Review

- Antisocial Behavior

- The Development of Aggression and Other Antisocial Behaviors

- Consistency of Aggressive and Antisocial Behavior

- Box 14.3: A Closer Look Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder

- Characteristics of Aggressive-Antisocial Children and Adolescents

- The Origins of Aggression

- Box 14.4: Applications The Fast Track Intervention

- Biology and Socialization: Their Joint Influence on Children’s Antisocial Behavior

- Review

- Chapter Summary

554

Themes

Nature and Nurture

Nature and Nurture

The Active Child

The Active Child

Continuity/Discontinuity

Continuity/Discontinuity

Mechanisms of Change

Mechanisms of Change

The Sociocultural Context

The Sociocultural Context

Individual Differences

Individual Differences

Research and Children’s Welfare

Research and Children’s Welfare

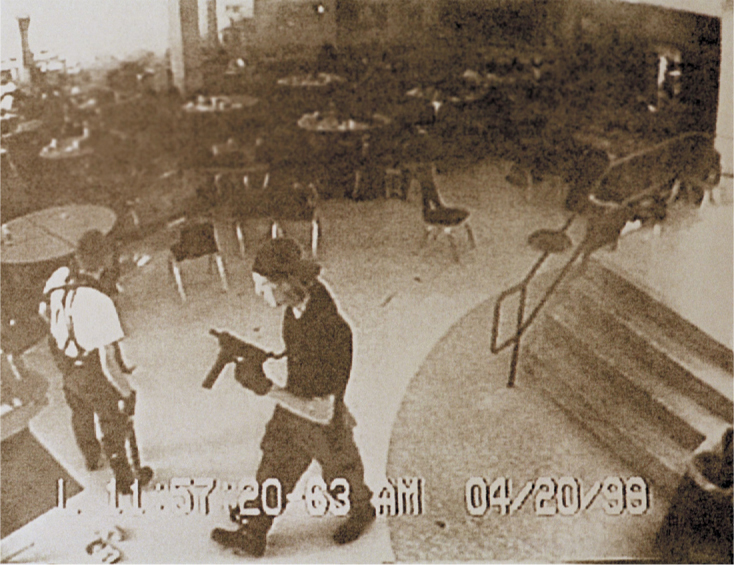

n April 1999, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, two students at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, killed a dozen students and a teacher and injured 23 other persons. As terrible as this incident was, it could have been much worse. The two adolescents, who had planned the massacre carefully for months, had actually prepared 95 explosive devices that did not go off because of an electronic failure. One set of explosives was supposed to go off in the cafeteria, killing many students and forcing others to flee into the schoolyard, where Harris and Klebold had planned to hide in wait and gun them down. Another set of explosives in the killers’ cars in the school parking lot was timed to explode after the police and paramedics arrived on the scene, causing more death and chaos.

n April 1999, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, two students at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, killed a dozen students and a teacher and injured 23 other persons. As terrible as this incident was, it could have been much worse. The two adolescents, who had planned the massacre carefully for months, had actually prepared 95 explosive devices that did not go off because of an electronic failure. One set of explosives was supposed to go off in the cafeteria, killing many students and forcing others to flee into the schoolyard, where Harris and Klebold had planned to hide in wait and gun them down. Another set of explosives in the killers’ cars in the school parking lot was timed to explode after the police and paramedics arrived on the scene, causing more death and chaos.

In videotapes made weeks before the attacks, the boys gleefully predicted that they would kill 250 people and bragged about the publicity they would get for their actions. They also made it clear that their attack was payback for having been humiliated and rejected by their peers: on one videotape, Harris, holding a sawed-off shotgun, declared, “Isn’t it fun finally to get the respect that we are going to deserve?” (quoted in Aronson, 2000, p. 86).

One might think that Harris and Klebold had suffered terrible childhoods. Yet, from all reports, their parents were probably more supportive than the average parents. And although the pair did endure considerable peer rejection at Columbine, Harris, at least, was a fairly popular student at his school in Plattsburgh, New York, before he moved to Littleton. Explanations for why Harris and Klebold did what they did are not as simple as they might initially seem.

In striking contrast to the lethally self-centered actions of Harris and Klebold, in the midst of the carnage, some students stayed with and tried to assist a teacher and other students who were shot. One boy running for his life helped a badly wounded girl get to an exit. Another boy draped himself over his sister and her friend to protect them from being shot (Gibbs, 1999). These students were concerned with others’ lives even when their own were at risk.

The Columbine tragedy and more recent incidents, like the 2012 Sandy Hook school slayings in Connecticut, are additions to a long list of incidents that raise questions about why some adolescents become involved in antisocial and illegal behavior, ranging from vandalism and other forms of delinquency to horrific violent crime. The starting point for finding answers to these questions is understanding the aspects of children’s thinking and behavior that contribute to morality.

To act in moral ways on a regular basis, children must have an understanding of right and wrong and the reasons why certain actions are moral or immoral. In addition, they must have a conscience, that is, they must be concerned about acting in a moral manner and feel guilty when they do not. When studying moral development, researchers have focused on a number of different questions related to these requirements. How do children think about moral issues and how does that thinking change with age? Does children’s reasoning about moral issues relate to their behavior? How early do caring and sharing, or aggression and cruelty, first appear in children? What factors contribute to differences among children in the degree to which they display helpful and caring or antisocial behaviors? Can steps be taken to help children develop caring and helpful behaviors and reduce the likelihood of their developing immoral or antisocial behaviors?

555

We start our discussion of moral development by examining children’s moral judgment—that is, how children think about situations involving moral decisions. Then we examine findings on the early emergence of conscience and the development of prosocial behaviors—behaviors such as helping and sharing that benefit others. Next, we turn to aggression and other antisocial behaviors such as stealing. As you will see, children’s moral development is influenced by advances in their social and cognitive capacities, as well as by genetic factors and environmental factors, including family and cultural influences. Therefore, the themes of individual differences, nature and nurture, and the sociocultural context will be prominent in our discussions. In addition, theory and research on moral judgment grew out of Piaget’s work in this area, which, like his theory on cognitive development (see Chapter 4), involves stages of development and assumes that children actively try to understand the world around them. Consequently, the themes of continuity/discontinuity, mechanisms of change, and the active child are evident in our consideration of the development of moral judgment. Also in play is the theme of research and children’s welfare, as we survey intervention programs that are designed to promote prosocial thinking and behavior and prevent antisocial behavior.