Antisocial Behavior

Pick up any newspaper and you are inevitably reminded of the antisocial, often violent behavior that is commonplace among youth in urban, industrialized countries, especially in Western societies. In the United States in 2009, juveniles younger than 18 were involved in 9% of murder arrests, 12% of aggravated assault arrests, 25% of burglary arrests, 25% of robbery arrests, 14% of rapes, 15% of all violent crimes, and 24% of all property crimes (Puzzanchera, Adams, & Hockenberry, 2012).

Because youths are easier to arrest than adults are, these statistics likely over-estimate their criminal behavior. However, in cases that were closed, juveniles were involved in 11% of all violent crime, including 5% of murders and 11% of rapes, and 15% of all property crime (Puzzanchera et al., 2012). Statistics like these, along with incidents like the Columbine tragedy described at the beginning of the chapter, raise questions such as: Are youths who commit violent acts already aggressive in childhood? How do levels of aggression change with development? What factors contribute to individual differences in children’s antisocial behavior? As we address these issues, the themes of individual differences, nature and nurture, the sociocultural context, and research and children’s welfare will be particularly salient.

The Development of Aggression and Other Antisocial Behaviors

aggression  behavior aimed at harming or injuring others

behavior aimed at harming or injuring others

Aggression is behavior aimed at harming others (Parke & Slaby, 1983), and it is behavior that emerges quite early. How early? Instances of aggression over the possession of objects occur between infants before 12 months of age—especially behaviors such as trying to tug objects away from each other (D. F. Hay, Mundy et al., 2011)—but most do not involve bodily contact such as hitting (Coie & Dodge, 1998; D. F. Hay & Ross, 1982). Beginning at around 18 months of age, physical aggression such as hitting and pushing—particularly over the possession of objects—increases in frequency until about age 2 or 3 (Alink et al., 2006; D. F. Hay, Hurst et al., 2011; D. S. Shaw et al., 2003). Then, with the growth of language skills, physical aggression decreases in frequency, and verbal aggression such as insults and taunting increases (Bonica et al., 2003; Dionne et al., 2003; Mesman et al., 2009; Miner & Clarke-Stewart, 2008).

578

instrumental aggression  aggression motivated by the desire to obtain a concrete goal

aggression motivated by the desire to obtain a concrete goal

Among the most frequent causes of aggression in the preschool years are conflicts between peers over possessions (Fabes & Eisenberg, 1992; Shantz, 1987) and conflict between siblings over most anything (Abramovitch, Corter, & Lando, 1979). Conflict over possessions often is an example of instrumental aggression, that is, aggression motivated by the desire to obtain a concrete goal, such as gaining possession of a toy or getting a better place in line. Preschool children sometimes also use relational aggression (Crick, Casas, & Mosher, 1997), which, as explained in Chapter 13, is intended to harm others by damaging their peer relationships. Among preschoolers, this typically involves excluding peers from a play activity or a social group (M. K. Underwood, 2003).

The drop in physical aggression in the preschool years is likely due to a variety of factors, including not only children’s increasing ability to use verbal and relational aggression but also their developing ability to use language to resolve conflicts and to control their own emotions and actions (Coie & Dodge, 1998). Thus, overt physical aggression continues to remain low or to decline in frequency for most children during elementary school, although a relatively small group of children—primarily boys (Moffitt & Caspi, 2001; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2004)—develop frequent and serious problems with aggression and antisocial behavior at this age (Cairns et al., 1989; S. B. Campbell et al., 2010; D. S. Shaw et al., 2003) or in early adolescence (Xie, Drabick, & Chen, 2011).

Whereas aggression in young children is usually instrumental, aggression in elementary school children often is hostile, arising from the desire to hurt another person or the need to protect oneself against a perceived threat to self-esteem (Dodge, 1980; Hartup, 1974). Children who engage in physical aggression tend to also engage in relational aggression (Card et al., 2008), with the degree to which they use one or the other tending to be consistent across childhood (Ostrov et al., 2008; Vaillancourt et al., 2003). Overall, the frequency of overt aggression decreases for most teenagers (Di Giunta et al., 2010; Loeber, 1982), at least after mid-adolescence (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2008).

In childhood, covert types of antisocial behaviors such as stealing, lying, and cheating also occur with considerable frequency and begin to be characteristic of some children with behavioral problems (Loeber & Schmaling, 1985). Compared with overt antisocial behavior, a high level of such covert behavior in the early school years has been found to be an even better predictor of a range of antisocial behavior 3 to 4 years later (J. J. Snyder et al., 2012).

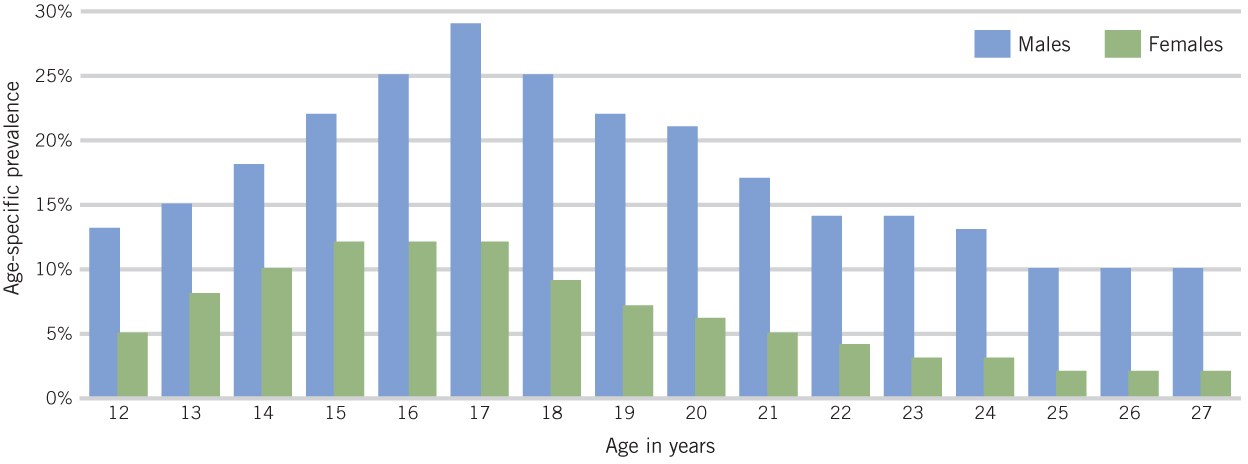

In mid-adolescence, serious acts of violence increase markedly, as do property offenses and status offenses such as drinking and truancy (Lahey et al., 2000). As illustrated in Figure 14.3, adolescent violent crime peaks at age 17, when 29% of males and 12% of females report committing at least one serious violent offense. As the figure also shows, male adolescents and adults engage in much more violent behavior and crime than do females (Coie & Dodge, 1998; Elliott, 1994)—although in 2009, 29% of the arrests among juveniles were of females (Puzzanchera, 2009), who made up 17% of the juvenile arrests for violent crime and 35% of the juvenile arrests for property crime.

579

Consistency of Aggressive and Antisocial Behavior

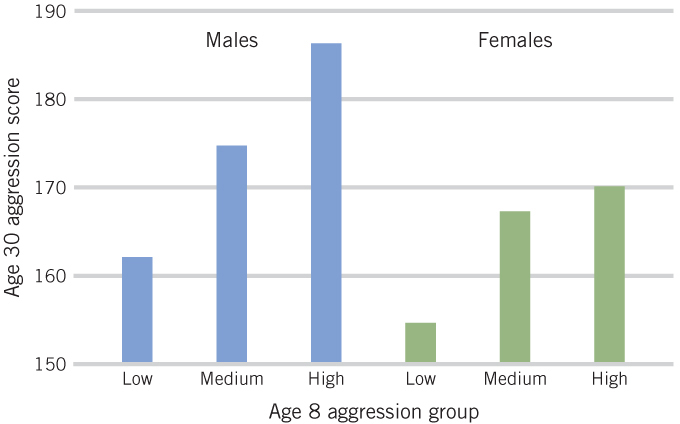

There is considerable consistency in both girls’ and boys’ aggression across childhood and adolescence. Children who are the most aggressive and prone to conduct problems such as stealing in middle childhood tend to be more aggressive and delinquent in adolescence than children who develop conduct problems at a later age (Broidy et al., 2003; Burt et al., 2000; Lahey, Goodman et al., 1999; Schaeffer et al., 2003). This holds especially true for boys (Fontaine et al., 2009). In one study, children who had been identified as aggressive by their peers when they were 8 years old had more criminal convictions and engaged in more serious criminal behavior at age 30 than did those who had not been identified as aggressive (see Figure 14.4) (Eron et al., 1987). In another study of girls only, relational aggression in childhood was related to subsequent conduct disorders (Keenan et al., 2010). (Conduct disorders are discussed in Box 14.3.)

Many children who are aggressive from early in life have neurological deficits (i.e., brain dysfunctions) that underlie such problems as difficulty in paying attention and hyperactivity (Gatzke-Kopp et al., 2009; Moffitt, 1993a; Speltz et al., 1999; Viding & McCrory, 2012). These deficits, which may become more marked with age (Aguilar et al., 2000), can result in troubled relations with parents, peers, and teachers that further fuel the child’s aggressive, antisocial pattern of behavior. Problems with attention are particularly likely to have this effect because they make it difficult for aggressive children to carefully consider all the relevant information in a social situation before deciding how to act; thus, their behavior often is inappropriate for the situation. In addition, callous, unemotional traits, which often accompany aggression and conduct disorder (e.g., Keenan et al., 2010), appear to be associated with a delay in cortical maturation in brain areas involved in decision making, morality, and empathy (De Brito et al., 2009).

580

Box 14.2: a closer look

OPPOSITIONAL DEFIANT DISORDER AND CONDUCT DISORDER

oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)  a disorder characterized by age-inappropriate and persistent displays of angry, defiant, and irritable behaviors

a disorder characterized by age-inappropriate and persistent displays of angry, defiant, and irritable behaviors

If a child’s problem behaviors become serious, the child is likely to be diagnosed by psychologists and physicians as having a clinical disorder. Two such disorders that involve antisocial behavior are oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) is characterized by angry, defiant behavior that is age-inappropriate and persistent (lasting at least 6 months). Children with ODD typically lose their temper easily, arguing with adults and actively defying their requests or rules. They are also prone to blame others for their own mistakes or misbehavior and are often spiteful or vindictive. Conduct disorder (CD) includes more severe antisocial and aggression behaviors that inflict pain on others (e.g., initiating fights, cruelty to animals) or involve the destruction of property or the violation of the rights of others (e.g., stealing, robberies).

conduct disorder (CD)  a disorder that involves severe antisocial and aggression behaviors that inflict pain on others or involve destruction of property or denial of the rights of others

a disorder that involves severe antisocial and aggression behaviors that inflict pain on others or involve destruction of property or denial of the rights of others

Other diagnostic signs include frequently running away from home, frequently staying out all night before age 13 despite parental prohibitions, or persistent school truancy beginning prior to age 13. To warrant a diagnosis of ODD or CD, children must exhibit multiple, persistent symptoms that are clearly impairing, distinguishing them from those youngsters who display the designated behaviors on an infrequent or inconsistent basis (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Hinshaw & Lee, 2003).

There is debate in the field regarding how antisocial behavior, including ODD and CD, should be conceptualized. Some experts argue that antisocial behavior should be viewed in terms of a continuum from infrequent to frequent displays of externalizing symptoms. Others argue that extreme forms of antisocial behavior are qualitatively different from garden-variety types of externalizing behaviors. In other words, there is a question regarding whether children with ODD or CD simply have more, or more severe, externalizing problems than do better-adjusted youth, or whether their problems are of an altogether different type. The answer to this question is not clear. However, the fact that more externalizing symptoms at a younger age predict serious diagnosed problems in adolescence or adulthood (Biederman et al., 2008; Côté et al., 2001; Hinshaw & Lee, 2003) is viewed by some as evidence that serious externalizing problems differ in their origins from less severe types of such behavior.

Estimates of the prevalence of ODD and CD range widely (Hinshaw & Lee, 2003). A median prevalence estimate for ODD among U.S. youth is about 3% (Lahey, Goodman et al., 1999). The American Psychiatric Association (1994) has estimated that the rate of CD for children and adolescents is 6% to 16% for boys and 2% to 9% for girls. In one large study in Canada, the rates were approximately 8% for boys and 3% for girls (Offord, Alder, & Boyle, 1986). The average age of onset for ODD is approximately 6 years of age; for CD it is 9 years of age (Hinshaw & Lee, 2003). For girls, the onset of CD after age 9 is perhaps 10% (Keenan et al., 2010).

Although there is debate in regard to the relation between ODD and CD, some children develop both CD and ODD, whereas others do not. A minority of youth with ODD later develop CD; however, those children or adolescents with CD often, but not always, had ODD first (Loeber & Burke, 2011; van Lier et al., 2007). In many instances, youth with ODD or CD also have been diagnosed with other disorders such as anxiety disorder or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (about half of youth with ODD or CD also have attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder) (Hinshaw & Lee, 2003). The two disorders also seem to differ somewhat in their prediction of later problem behaviors: CD has been found to predict primarily behavioral problems in early adulthood, including antisocial behavior, whereas ODD shows stronger prediction of emotional disorders in early adulthood (Loeber & Burke, 2011; R. Rowe et al., 2010).

The factors related to the development of CD or ODD are similar to those related to the development of aggression. Genetics play a role, although heritability seems to be stronger for early-onset and overt types of antisocial behavior (such as aggression) than for later-onset or covert forms of antisocial behavior (such as stealing) (Hinshaw & Lee, 2003; Lahey, Goodman et al., 2009; Maes et al., 2007; Meier et al., 2011). Environmental risks for these disorders include such factors as living in a disadvantaged, risky neighborhood or in a stressed, lower-SES family; parental abuse; poor parental supervision; and harsh and inconsistent discipline (Goodnight et al., 2012; Hinshaw & Lee, 2003; R. Rowe et al., 2010). Peer rejection and associating with deviant peers are also linked with ODD and CD (Hinshaw & Lee, 2003; Loeber & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1986). It is likely that a variety of these factors jointly contribute to children’s developing ODD or CD and that the most important factors vary according to the age of onset, the specific problem behaviors, and individual characteristics of the children, including their temperament and intelligence.

Early-onset conduct problems are also associated with a range of family risk factors. These include the mother’s being single at birth, the mother’s being stressed prenatally and during the child’s preschool years; the mother’s being psychologically unavailable in the preschool years; parental antisocial tendencies; low maternal education and poverty; and child neglect and physical abuse (S. B. Campbell et al., 2010; D. F. Hay et al., 2011; K. M. McCabe et al., 2001; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2004; M. Robinson et al., 2011).

581

Adolescents with a long childhood history of troubled behavior represent only a minority of adolescents who engage in the much broader problem of “juvenile delinquency” (Hämäläinen & Pulkkinen, 1996). Indeed, most adolescents who perform delinquent acts have no history of aggression or antisocial behavior before age 11 (Elliott, 1994). For some, delinquency may occur in response to the normal pressures of adolescence, as when they attempt to assert their independence from adults or win acceptance from their peers. However, the onset of antisocial behavior in adolescence is also predicted by economic disadvantage, being a member of an ethnic minority, interacting with deviant peers (see Chapter 13), and having a difficult, irritable temperament from infancy onward (K. M. McCabe et al., 2001, 2004; Roisman et al., 2010).

Youths who develop problem behaviors in adolescence typically stop engaging in antisocial behavior later in adolescence or early adulthood (Moffitt, 1993a). However, some—especially those who have low impulse control, poor regulation of aggression, and a weak orientation toward the future (Monahan et al., 2009)—continue to engage in problem behaviors and to have some problems with their mental health and substance dependence until at least their mid-20s (Moffitt et al., 2002).

Characteristics of Aggressive-Antisocial Children and Adolescents

Aggressive-antisocial children and adolescents differ, on average, from their nonaggressive peers in a variety of characteristics. These include having a difficult temperament and the tendency to process social information in negative ways.

Temperament and Personality

Children who develop problems with aggression and antisocial behavior tend to exhibit a difficult temperament and a lack of self-regulatory skills from a very early age (Espy et al., 2011; Rothbart, 2012; Yaman et al., 2010). Longitudinal studies have shown, for example, that infants and toddlers who frequently express intense negative emotion and demand much attention tend to have higher levels of problem behaviors such as aggression from the preschool years through high school (J. E. Bates et al., 1991; Joussemet et al., 2008; Olson et al., 2000). Similarly, preschoolers who exhibit lack of control, impulsivity, high activity level, irritability, and distractibility are prone to fighting, delinquency, and other antisocial behavior at ages 9 through 15; to aggression and criminal behavior in late adolescence; and, in the case of men, to violent crime in adulthood (Caspi et al., 1995; Caspi & Silva, 1995; Tremblay et al., 1994). However, children who use aggression to achieve instrumental goals are less prone to unregulated negative emotion and physiological responding than those who exhibit angry responses to provocation (Scarpa et al., 2010; Vitaro et al., 2006).

Some aggressive children and adolescents tend to feel neither guilt nor empathy or sympathy for others (de Wied et al., 2012; Lotze et al., 2010; R. J. McMahon, Witkiewitz, & Kotler, 2010; Pardini & Byrd, 2012; Stuewig et al., 2010). They are often charming, but insincere and callous. The combination of impulsivity, problems with attention, and callousness in childhood is especially likely to predict aggression, antisocial behavior, and run-ins with the police in adolescence (Christian et al., 1997; Frick & Morris, 2004; Hastings et al., 2000) and perhaps in adulthood as well (Lynam, 1996).

582

Social Cognition

In addition to their differences in temperament, aggressive children differ from nonaggressive children in their social cognition. As discussed in Chapter 9, aggressive children tend to interpret the world through an “aggressive” lens. They are more likely than nonaggressive children to attribute hostile motives to others in contexts in which the other person’s motives and intentions are unclear (the “hostile attributional bias”) (Dodge et al., 2006; Lansford et al., 2010; MacBrayer et al., 2003; D. A. Nelson, Mitchell, & Yang, 2008). Compared with those of nonaggressive peers, their goals in such social encounters are also more likely to be hostile and inappropriate to the situation, typically involving attempts to intimidate or get back at a peer (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Slaby & Guerra, 1988). Correspondingly, when asked to come up with possible solutions to a negative social situation, aggressive children generate fewer options than do nonaggressive children, and those options are more likely to involve aggressive or disruptive behavior (Deluty, 1985; Slaby & Guerra, 1988).

In line with these tendencies, aggressive children are also inclined to evaluate aggressive responses more favorably, and competent, prosocial responses less favorably, than do their nonaggressive peers (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Dodge et al., 1986), especially as they get older (Fontaine et al., 2010). In part, this is because they feel more confident of their ability to perform acts of physical and verbal aggression (Barchia & Bussey, 2011; Quiggle et al., 1992), and they expect their aggressive behavior to result in positive outcomes (e.g., getting their way) as well as to reduce negative treatment by others (Dodge et al., 1986; Perry, Perry, & Rasmussen, 1986). Given all this, it is not surprising that aggressive children are predisposed to aggressive behavioral choices (Calvete & Orue, 2012; Dodge et al., 2006). This aggressive behavior, in turn, appears to increase children’s subsequent tendency to positively evaluate aggressive interpersonal behaviors, further increasing the level of future antisocial conduct (Fontaine et al., 2008).

reactive aggression  emotionally driven, antagonistic aggression sparked by one’s perception that other people’s motives are hostile

emotionally driven, antagonistic aggression sparked by one’s perception that other people’s motives are hostile

It is important to note, however, that although all these aspects of functioning contribute to the prediction of children’s aggression, not all aggressive children exhibit the same biases in social cognition. Children who are prone to emotionally driven, hostile aggression—labeled reactive aggression—are particularly likely to perceive others’ motives as hostile (Crick & Dodge, 1996), to initially generate aggressive responses to provocation, and to evaluate their responses as morally acceptable (Arsenio, Adams, & Gold, 2009; Dodge et al., 1997). In contrast, children who are prone to proactive aggression—which, like instrumental aggression, is aimed at fulfilling a need or desire—tend to anticipate more positive social consequences for aggression (Arsenio, Adams, & Gold, 2009; Crick & Dodge, 1996; Dodge et al., 1997; Sijtsema et al., 2009).

proactive aggression  unemotional aggression aimed at fulfilling a need or desire

unemotional aggression aimed at fulfilling a need or desire

The Origins of Aggression

What are the causes of aggression in children? Key contributors include genetic makeup, socialization by family members, the influence of peers, and cultural factors.

583

Biological Factors

Biological factors undoubtedly contribute to individual differences in aggression, but their precise role is not very clear. Twin studies suggest that antisocial behavior runs in families and is partially due to genetic factors (Arsenault et al., 2003; Rhee & Waldman, 2002; Waldman et al., 2011). In addition, heredity appears to play a stronger role in aggression in early childhood and adulthood than it does in adolescence, when environmental factors are a major contributor to aggression (Rende & Plomin, 1995; J. Taylor, Iacono, & McGue, 2000). Heredity also contributes to both proactive and reactive aggression, but in terms of stability of individual differences in aggression and the association of aggression with psychopathic traits (e.g., callousness, lack of affect, including lack of remorse, and manipulativeness), the influence of heredity is greater for proactive aggression (Bezdjian et al., 2011; Tuvblad et al., 2009).

We have already noted one genetically influenced contributor to aggression—difficult temperament. Hormonal factors are also assumed to play a role in aggression, although the evidence for this assumption is mixed. For example, testosterone levels seem to be related to activity level and responses to provocation, and high testosterone levels sometimes have been linked to aggressive behavior (Archer, 1991; Hermans, Ramsey, & van Honk, 2008). However, the relation of testosterone to aggression, although statistically significant, is quite small (Book, Starzyk, & Quinsey, 2001).

Another biological contributor to aggression discussed earlier is neurological deficits that affect attention and regulatory capabilities (Moffitt, 1993b): children who are not well regulated are likely to have difficulty controlling their tempers and inhibiting aggressive impulses (N. Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Eggum, 2010; N. Eisenberg, Valiente et al., 2009; Y. Xu, Farver, & Zhang, 2009).

Whatever their specific role, the biological correlates of aggression probably are neither necessary nor sufficient to cause aggressive behavior in most children. Genetic, neurological, or hormonal characteristics may put a child at risk for developing aggressive and antisocial behavior, but whether the child becomes aggressive will depend on numerous factors, including experiences in the social world. We return to the joint role of genetics and the environment in aggression shortly.

Socialization of Aggression and Antisocial Behavior

Many people, including some legislators and judges, feel that the development of aggression can be traced back to socialization in the home. And, in fact, the quality of parenting experienced by antisocial children is poorer than that experienced by other children (Dodge et al., 2006; Scaramella et al., 2002). For example, children in chaotic homes—characterized by a lack of order and structure, few predictable routines, and noise—tend to be relatively high in disruptive behavior, and this relation appears not to be due to genetics (Jaffee et al., 2012). Although it is unclear to what degree poor parenting and chaotic homes, in and of themselves, may account for children’s antisocial behavior, it is clear that they comprise several factors that can promote such behavior.

Parental punitiveness Many children whose parents often use harsh but non-abusive physical punishment are prone to problem behaviors in the early years, aggression in childhood, and criminality in adolescence and adulthood (Burnette et al., 2012; Gershoff, 2002; Gershoff et al., 2010; Gershoff et al., 2012; Olson et al., 2011). This is especially true when the parents are cold and punitive in general (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997), when the child does not have an early secure attachment (Kochanska et al., 2009; Kochanska & Kim, 2012), and when the child has a difficult temperament and is chronically angry and unregulated (Kochanska & Kim, 2012; Mulvaney & Mebert, 2007; Y. Xu et al., 2009; Yaman et al., 2010).

584

It is important to note, however, that the relation between physical punishment and children’s antisocial behavior varies across racial, ethnic, and cultural groups. As discussed in Chapter 12, in some cultures and subcultures, physical punishment and controlling parental behaviors are viewed as part of responsible parenting when coupled with parental support and normal demands for compliance. When this is the case, parental punishment tends not to be associated with antisocial behavior because children might see authoritarian parenting as protective and caring (Lansford et al., 2006). Although corporal punishment, as well as yelling and screaming, tends to be associated with higher levels of aggression in children in a number of diverse cultures, including China, India, Kenya, Italy, Philippines, and Thailand, this relation is weaker if children view such parenting as normative (Gershoff et al., 2010).

In contrast, abusive punishment is likely to be associated with the development of antisocial tendencies regardless of the group in question (Deater-Deckard et al., 1995; Luntz & Widom, 1994; Weiss et al., 1992). Very harsh physical discipline appears to lead to the kinds of social cognition that are associated with aggression, such as assuming that others have hostile intentions, generating aggressive solutions to interpersonal problems, and expecting aggressive behavior to result in positive outcomes (Alink et al., 2012; Dodge et al., 1995).

In addition, parents who use abusive punishment provide salient models of aggressive behavior for their children to imitate (Dogan et al., 2007). Ironically, children who are subjected to such punishment are likely to be anxious or angry and therefore are unlikely to attend to their parents’ instructions or demands or to be motivated to behave as their parents wish them to (M. L. Hoffman, 1983).

There probably is a reciprocal relation between children’s behavior and their parents’ punitive discipline (Arim et al., 2011; N. Eisenberg, Fabes et al., 1999). That is, children who are high in antisocial behavior, exhibit psychopathic traits (e.g., are callous, unemotional, manipulative, remorseless), or are low in self-regulation tend to elicit harsh parenting (Lansford et al., 2009; Salihovic et al., 2012); in turn, harsh parenting increases the children’s problem behavior (Sheehan & Watson, 2008). However, some recent research suggests that harsh physical punishment has a stronger effect on children’s externalizing problems than vice versa (Lansford et al., 2011).

The relation between punitive parenting and children’s aggression can, of course, have a genetic component. Parents whose children are antisocial and aggressive often are that way themselves and are predisposed to punitive parenting (Davies et al., 2012; Dogan et al., 2007; Thornberry et al., 2003). At the same time, however, twin studies indicate that the relation between punitive, negative parenting and children’s aggression and antisocial behavior is not entirely due to hereditary factors (Boutwell et al., 2011; Jaffee et al., 2004a; Jaffee et al., 2004b). In one study, for example, differences in punitive parenting with adolescent identical twins were related to differences in the twins’ aggression (Caspi et al., 2004). In another study, parent–adolescent conflict predicted more conduct problems over time (but not vice versa), even in adoptive families (Klahr et al., 2011). In neither of these studies can genetics explain the effects of parents’ behaviors on their children’s problem behaviors.

Ineffective discipline and family coercion Another factor that can increase children’s antisocial behavior is ineffective parenting. Parents who are inconsistent in administering discipline are more likely than other parents to have aggressive and delinquent children (Dumka et al., 1997; Frick, Christian, & Wootton, 1999; Sampson & Laub, 1994). So too are parents who fail to monitor their children’s behavior and activities. One reason parental monitoring may be important is that it reduces the likelihood that older children and adolescents will associate with deviant, antisocial peers (Dodge et al., 2008; G. R. Patterson, Capaldi, & Bank, 1991). It also makes it more likely that parents will know if their children are engaging in antisocial behavior. At the same time, however, parents of difficult, aggressive youth sometimes find that monitoring leads to such conflict with their children that they are forced to back off (Laird et al., 2003).

585

Ineffective discipline is often evident in the pattern of troubled family interaction described by G. R. Patterson (1982, 1995; J. Snyder et al., 2005) and discussed in Chapter 1. In this pattern, the aggression of children who are out of control may be unintentionally reinforced by parents who, once their efforts to coerce compliance have failed, give in to their children’s fits of temper and demands (J. Snyder, Reid, & Patterson, 2003). This is especially probable in the case of out-of-control boys, who are much more likely than other boys to react negatively to their mother’s attempts to discipline them (G. R. Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992). Whether maternal coercion elicits the same pattern of response from girls as from boys is not yet known because most of the relevant research has been done with boys, but there is some reason to believe that it does not (McFadyen-Ketchum et al., 1996).

Parental conflict Children who are frequently exposed to verbal and physical violence between their parents tend to be more antisocial and aggressive than other children (Cummings & Davies, 2002; R. Feldman, Masalha, & Derdikman-Eiron, 2010; Keller et al., 2008; Van Ryzin & Dishion, 2012). This relation holds true even when genetic factors that might have caused it are taken into account (Jaffee et al., 2002). One obvious reason for this is that embattled parents model aggressive behavior for their children. Another is that children whose mothers are physically abused tend to believe that violence is an acceptable, even natural part of family interactions (Graham-Bermann & Brescoll, 2000). Compared with spouses who get along well with each other, embattled spouses also tend to be less skilled and responsive, and more hostile and controlling, in their parenting (Buehler et al., 1997; Davies et al., 2012; Emery, 1989; Gonzales et al., 2000), which, in turn, can increase their children’s aggressive tendencies (Li et al., 2011). This pattern, in which marital hostility predicts hostile parenting, which, in turn, predicts children’s aggression, has also been found in families with an adopted child, so these relations cannot be due solely to genes shared by parents and children (Stover et al., 2012).

Socioeconomic status and children’s antisocial behavior Children from low-income families tend to be more antisocial and aggressive than children from more prosperous homes (Goodnight et al., 2012; Keiley et al., 2000; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2004; Stouthamer-Loeber et al., 2002). This pattern is highlighted by the finding that when families escaped from poverty, 4- to 7-year-old children tended to become less aggressive and antisocial, whereas families’ remaining in poverty or moving into poverty for the long-term was associated with an increase in children’s antisocial behavior (Macmillan et al., 2004). There are many reasons that might account for such differences in trajectories.

586

One major reason is the greater amount of stressors experienced by children in poor families, including stress in the family (illness, domestic violence, divorce, legal problems) and neighborhood violence (Vanfossen et al., 2010). In addition, as discussed in Chapter 12, low SES tends to be associated with living in a single-parent family or being an unplanned child of a teenage parent, and stressors of these sorts are linked to increased aggression and antisocial behavior (Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1994; Linares et al., 2001; Tolan, Gorman-Smith, & Henry, 2003; Trentacosta et al., 2008). Also, because of the many stressors they face, impoverished parents are more likely than other parents to be rejecting and low in warmth; to use erratic, threatening, and harsh discipline; and to be lax in supervising their children (Conger et al., 1994; Dodge et al., 1994; Odgers et al., 2012).

In addition to all these low-SES risk factors, conditions such as the presence of gangs, the lack of jobs for juveniles, and few opportunities to engage in constructive activities (e.g., clubs and sports) also likely contribute to the antisocial behavior of many youths in poor neighborhoods.

Peer Influence

As we discussed in Chapter 13, aggressive children tend to socialize with other aggressive children and often become more delinquent over time if they have close friends who are aggressive. Moreover, the expression of a genetic tendency toward aggression is stronger for individuals who have aggressive friends (Brendgen et al., 2008).

The larger peer group with whom older children and adolescents socialize may influence aggression even more than their close friends do (Coie & Dodge, 1998). In one study, boys exposed to peers involved in overt antisocial behaviors, such as violence and the use of a weapon, were more than three times as likely as other boys to engage in such acts themselves (Keenan et al., 1995). Associating with delinquent peers tends to increase delinquency because these peers model and reinforce antisocial behavior in the peer group. At the same time, participating in delinquent activities brings adolescents into contact with more delinquent peers (Dishion et al., 2010; Dishion et al., 2012; Lacourse et al., 2003; Thornberry et al., 1994).

Although research findings vary somewhat, it appears that children’s susceptibility to peer pressure to become involved in antisocial behavior increases in the elementary school years, peaks at about 8th or 9th grade, and declines thereafter (Berndt, 1979; B. B. Brown, Clasen, & Eicher, 1986; Steinberg & Silverberg, 1986). Although not all adolescents are susceptible to negative peer influence (Allen, Porter, & McFarland, 2006), even popular youth in early adolescence tend to increase participation in minor levels of drug use and delinquency if these behaviors are approved by peers (Allen et al., 2005). Peer approval of relational aggression increases in middle school, and students in peer groups supportive of relational aggression become increasingly aggressive (N. E. Werner & Hill, 2010). However, there are exceptions to this overall pattern that appear to be related to cultural factors. For example, Mexican American immigrant youth who are less acculturated, and therefore more tied to traditional values, appear to be less susceptible to peer pressure toward antisocial behavior than are Mexican American children who are more acculturated. Thus, it may be that peers play less of a role in promoting antisocial behavior for adolescents who are embedded in a traditional culture oriented toward adults’ expectations (e.g., deference and courtesy toward adults and adherence to adult values) (Wall et al., 1993).

587

Gangs An important peer influence on antisocial behavior can be membership in a gang. It was estimated that in the United States in 2010, there were 29,400 youth gangs with 756,000 active members (Egley & Howell, 2012). Most gangs are in metropolitan areas. In Los Angeles, for example, it is estimated that there are more than 450 gangs, with a combined total of 45,000 gang members (Los Angeles Police Department, 2013). However, since 1993, the presence of gangs in suburban and rural areas has increased (Egley & O’Donnell, 2009; H. N. Snyder & Sickmund, 1999; see Table 14.5). In many other countries, youth gangs are likewise becoming, or are likely to become, a serious problem (Vittori, 2007).

Gangs tend to be composed of young people who are similar in ethnic and racial background. The average age of gang members is between 17 and 18 years, with about half being 18 or older and a small portion being as young as 12 (Egley & Howell, 2012).

Adolescents are more likely to join gangs if they come from a neighborhood with a high rate of resident turnover, if they have an antisocial personality, and if they have psychopathic tendencies such as a combination of high hyperactivity, low anxiety, and low prosociality (Dupéré et al., 2007; Egan & Beadman, 2011). Adolescents who join gangs also tend to have engaged in antisocial activities and to have had delinquent friends before they joined. However, being in a gang appears to increase adolescents’ delinquent and antisocial behavior above their prior levels (Barnes, Beaver, & Miller, 2010; Delisi et al., 2009; Dishion et al., 2010; Lahey, Gordon et al., 1999). Not surprisingly, the longer adolescents remain in a gang, the more likely they are to engage in delinquent and antisocial behavior (Craig et al., 2002; Gordon et al., 2004).

Teens who are gang members are responsible for much of the serious violence in the United States (Huizinga as cited in Howell, 1998). From 2009 to 2011 in Los Angeles, for example, there were more 16,000 verified violent gang crimes, including 491 homicides. Much of this violence involves conflict within and between gangs. and gang members are much more likely than the rest of the population to be victims of violent crime (e.g., killed, robbed, or attacked), apparently in part because of their high involvement in delinquent activities and their ready access to drugs and alcohol (Delisi et al., 2009; T. J. Taylor et al., 2007; T. J. Taylor et al., 2008). Because youths who join gangs usually do poorly in school (Dishion et al., 2010), many inner-city gang members continue their membership in gangs rather than entering into conventional adult roles (Decker & van Winkle, 1996; Short, 1996).

Biology and Socialization: Their Joint Influence on Children’s Antisocial Behavior

As should be clear by now, it is very difficult to separate the specific biological, cultural, peer, and familial factors that affect the development of children’s antisocial behavior (Van den Oord et al., 2000). Nonetheless, it is clear that parents’ treatment of their children affects children’s aggression and antisocial behavior. Direct evidence of the role of parental effects can be found in intervention studies. When parents are trained to deal with their children in an effective manner, there are improvements in their children’s conduct problems (A. Connell et al., 2008; Dishion et al., 2008; Hanish & Tolan, 2001). Similar effects have been obtained in intervention studies in schools (see Box 14.4). Effects such as these indicate that socialization in and of itself plays a role in the development of antisocial behavior.

588

Box 14.4: applications

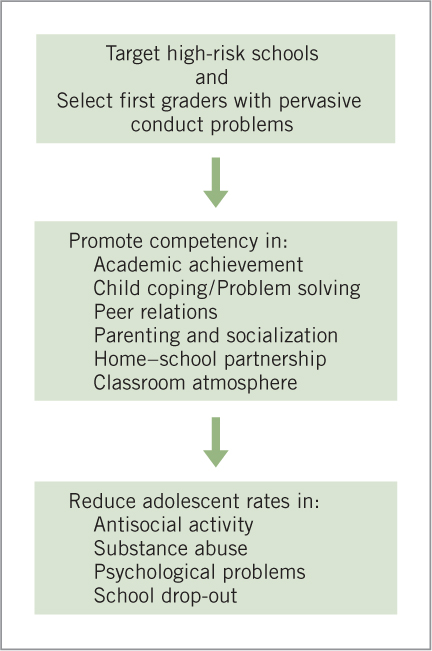

THE FAST TRACK INTERVENTION

Psychologists interested in the prevention of antisocial behavior and violence have designed numerous school-based intervention programs. One of the most intensive was Fast Track—a large, federally funded study that was tested in high-risk schools in four U.S. cities (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999a; 1999b). This program was initially implemented for 3 successive years with almost 400 1st-grade classes, half of which received the intervention and half of which served as a control group. The children in both groups tended to come from low-income families, about half of which were minority families (Slough, McMahon, & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2008).

There were two major parts of the intervention. In the first part, all children in the intervention classes were trained with a special curriculum designed to promote understanding and communication of emotions, positive social behavior, self-control, and social problem solving (Greenberg et al., 1995). The children were taught to recognize emotional cues in themselves and to distinguish appropriate and inappropriate behavioral reactions to emotions. They were also taught how to make and keep friends, how to share, how to listen to others, and how to calm themselves down and to inhibit aggressive behavior when they became upset or frustrated.

In the second part of the program, children with the most serious problem behaviors (about 10% of the group) participated in a more intensive intervention. In addition to the school intervention, they attended special meetings throughout the year, receiving social skills training similar to what they experienced in the classroom. They were also tutored in their school work. Their parents received group training that was designed to build their self-control and promote developmentally appropriate expectations for their child’s behavior. In addition, the program promoted parenting skills that would improve parent–child interaction, decrease children’s disruptive behavior, and establish a positive relationship between parents and the child’s school. After 1st grade, the curriculum was continued in the classrooms; other aspects of the intervention outside the classroom were adjusted to the needs of each family and child (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2004). Meetings with children and parents continued through the 9th grade.

The program was quite successful. In the 1st-grade classrooms as a whole, there was less aggression and disruptive behavior and a more positive atmosphere than in the control classes. More important, the children in the intervention group improved in their social and emotional skills (such as recognizing and coping with emotions), as well as in academic skills. They had more positive interactions with peers, were liked more by their classmates, and exhibited fewer conduct problems than the control children. Their parents improved in their parenting skills and were more involved with their children’s schooling.

In a follow-up at the end of 3rd grade, 37% of the children in the intervention group were found to be free of serious conduct problems, whereas only 27% of the children who did not receive the intervention were free of problems (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2002a). Teachers’ and parents’ reports, as well as school records, likewise indicated that there was a modest positive effect, both at home and in school, including the intervention group’s using special education services less and showing greater improvement in academic engagement. The intervention group also showed a modest increase in prosocial behavior. These effects generally were stronger in less disadvantaged schools, and effects on aggression were larger in students who showed higher baseline levels of aggression. In 4th and 5th grades, children in the intervention group still exhibited modest improvements in terms of conduct problems, peer acceptance, and lower levels of association with deviant peers. These positive outcomes seemed to be due, in part, to the effects of the intervention on reducing children’s hostile attribution biases, fostering their problem-solving skills, and reducing the levels of harsh parental discipline (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2002b, 2004; Bierman et al., 2010).

Across grades 3 to 12, the prevalence of externalizing problems such as conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder was reduced, although only for the youths most at risk (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2007, 2011). In addition, juvenile arrests were reduced, as were high-severity arrests in early adulthood for youths with the highest initial behavioral risk (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2010c). In terms of cost, it appears that, given the funds available, the program was not cost-efficient relative to the total sample but was likely cost-effective for the subgroup of children at high risk for externalizing problems (Foster & Jones, 2007). Thus, it is important that children be screened for inclusion in high-cost programs such as Fast Track (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2007).

Many interventions besides Fast Track have been devised to reduce children’s aggression and other externalizing problems. For example, numerous programs have been used to combat bullying in schools and the high-quality programs appear to reduce the incidence of bullying considerably (Cross et al., 2011; Salmivalli, Kärnä, & Poskiparta, 2011; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). More intensive programs tend to be more effective, and the most important elements of successful programs included parent meetings and training; teacher training and an emphasis on classroom management; firm disciplinary practices at school, including the enforcement of classroom rules; and a whole-school policy to eliminate bullying, improve playground supervision, and have children work in cooperative groups (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). Anti-bullying interventions appear to be more effective for adolescents than for younger children (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011).

Nonetheless, recent genetically informed research illustrates that often it is the combination of genetic and environmental factors that predict children’s antisocial, aggressive behavior and that some children are more sensitive to the quality of parenting than are others. As noted in our previous discussions of differential susceptibility (pages 409, 437, and 569), children with certain gene variants related to serotonin or dopamine, which affect neurotransmission, appear to be more reactive to their environment than are children with different variants. For example, under adverse conditions (e.g., chronic stress, poor parenting, socioeconomic deprivation), children with a particular variant of the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) or the dopamine receptor gene (DRD4) tend to be more aggressive than children with different variants of these gene (C. C. Conway et al., 2012) but, compared with those children, they tend to be less aggressive when they are in a supportive, resource-rich environment (Simons et al., 2011; Simons et al., 2012). In other cases, such gene variants are related to higher risk for aggression in adverse situations like maltreatment and divorce, but are not related to aggression in the absence of the adverse conditions (Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Thibodeau, 2012; Nederhof et al., 2012). Regardless of the exact nature of the gene–environment interaction, it seems clear that the degree of aggression is affected by a combination of heredity and the environment.

589

review:

Aggressive behavior emerges by the second year of life and increases in frequency during the toddler years. Physical aggression starts to decline in frequency in the preschool years; in elementary school, children tend to exhibit more nonphysical aggression (e.g., relational aggression) than at younger ages, and some children increasingly engage in antisocial behaviors such as stealing. Early individual differences in aggression and conduct problems predict antisocial behavior in later childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Children who first engage in aggressive, antisocial acts in early to mid-adolescence are less likely to continue their antisocial behavior after adolescence than are children who are aggressive and antisocial at a younger age.

590

Biological factors, including those related to temperament and neurological problems, likely affect children’s degree of aggression. Social cognition is also associated with aggressiveness in a variety of ways, including the attribution of hostile motives to others, having hostile goals, constructing and enacting aggressive responses in difficult situations, and evaluating aggressive responses favorably.

Children’s aggression is affected by a range of environmental factors, as well as by heredity. In general, low parental support, poor monitoring, or the use of disciplinary practices that are abusive or inconsistent are related to high levels of children’s antisocial behavior. Parental conflict in the home and many of the stresses associated with family transitions (e.g., divorce) and poverty can increase the likelihood of children’s aggression. In addition, involvement with antisocial peers likely contributes to antisocial behavior, although aggressive children also seek out antisocial peers. Cultural values and practices, as communicated in the child’s social world, also contribute to differences among children in aggressive behavior. Intervention programs can be used to reduce aggression, which provides evidence of the role of environmental factors in children’s aggression.