466

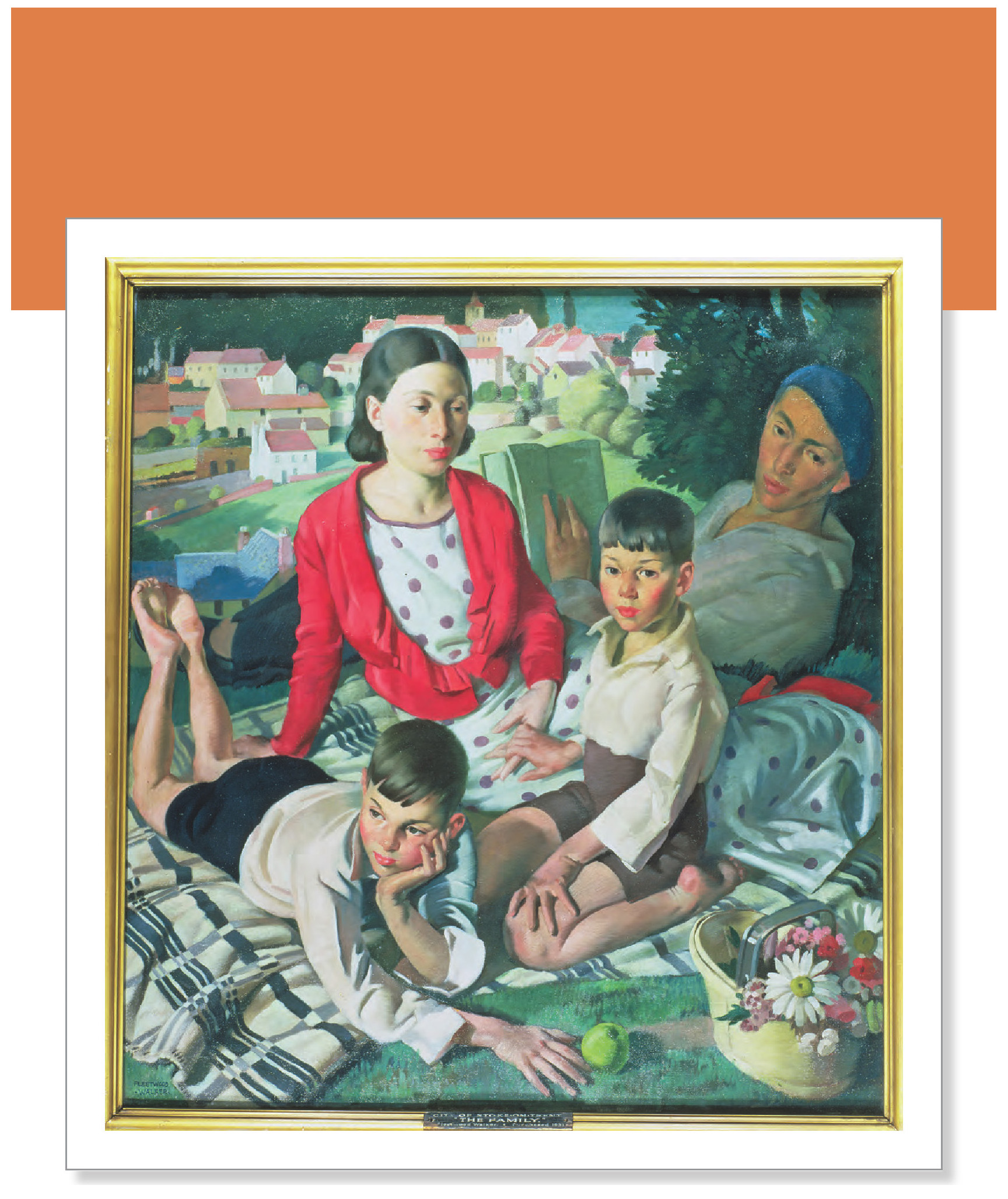

The Family

467

- Family Dynamics

- Box 12.1: A Closer Look Parent–Child Relationships in Adolescence

- Review

- The Role of Parental Socialization

- Parenting Styles and Practices

- The Child as an Influence on Parenting

- Socioeconomic Influences on Parenting

- Box 12.2: A Closer Look Homelessness

- Review

- Mothers, Fathers, and Siblings

- Differences in Mothers’ and Fathers’ Interactions with Their Children

- Sibling Relationships

- Review

- Changes in Families in the United States

- Box 12.3: Individual Differences Adolescents as Parents

- Older Parents

- Divorce

- Stepparenting

- Lesbian and Gay Parents

- Review

- Maternal Employment and Child Care

- The Effects of Maternal Employment

- The Effects of Child Care

- Review

- Chapter Summary

468

Themes

Nature and Nurture

Nature and Nurture

The Active Child

The Active Child

The Sociocultural Context

The Sociocultural Context

Individual Differences

Individual Differences

Research and Children’s Welfare

Research and Children’s Welfare

s noted in Chapter 2, in 1979, the People’s Republic of China announced a sweeping new policy that would affect Chinese families dramatically. Because of the many problems associated with the country’s overpopulation, the government ordered a limit of one child per family in urban populations. Backed up by a system of economic rewards for those who complied and financial and social sanctions against those who did not, this policy was quite effective, especially in urban areas. For example, in Shanghai in 1985, 98% of births were first births; across the country, the figure was 68% (Poston & Falbo, 1990). The Chinese government estimates that, as of 2009, the policy had prevented 250 to 300 million births (Y. Wang & Fong, 2009).

s noted in Chapter 2, in 1979, the People’s Republic of China announced a sweeping new policy that would affect Chinese families dramatically. Because of the many problems associated with the country’s overpopulation, the government ordered a limit of one child per family in urban populations. Backed up by a system of economic rewards for those who complied and financial and social sanctions against those who did not, this policy was quite effective, especially in urban areas. For example, in Shanghai in 1985, 98% of births were first births; across the country, the figure was 68% (Poston & Falbo, 1990). The Chinese government estimates that, as of 2009, the policy had prevented 250 to 300 million births (Y. Wang & Fong, 2009).

The one-child policy is controversial at a number of levels and has had a consequence that was unintended and grim: an epidemic of female abortion and infanticide arising from the cultural preference for male offspring. The controversies aside, however, the one-child policy provided developmental psychologists with an opportunity to study how a particular family structure might affect children’s development. Think about the differences in upbringing that might occur when parents have one child as opposed to two or more. To begin with, an only child is likely to receive more individual attention from parents and more of the family’s resources. In addition, an only child does not have to cooperate and share with siblings. Because of differences such as these, many people predicted that the new generation of single children raised in the People’s Republic of China would be overindulged and have little experience in compromising and cooperating with others. Thus, there was concern that these single children (called “onlies”) would become spoiled “little emperors” (Falbo & Poston, 1993). Such a concern was not confined to China. An increase of one-child families in the United States likewise raised worries that single children would become spoiled brats (Falbo & Polit, 1986).

In general, however, there is no consistent support for these concerns. There is some evidence that onlies in China, especially in urban areas, perform better on tests of academic performance and intelligence than do children from families with more than one child (Falbo & Poston, 1993; Falbo et al., 1989; Jiao, Ji, & Jing, 1996). And although some initial studies found that only children in China were viewed by peers as more self-interested and less cooperative than children with siblings (e.g., Jiao, Ji, & Jing, 1986), later studies found little evidence that only children have more behavioral problems (Hesketh et al., 2011; D. Wang et al., 2000; S. Zhang, 1997).

Moreover, large survey studies do not indicate that onlies are more prone to depression and anxiety (G. D. Edwards et al., 2005; Hesketh & Ding, 2005), despite the potential for heightened family pressures on them to fulfill parental goals and needs. In fact, there appears to be virtually no difference between onlies and other children in regard to personality or social behavior, including positive behaviors needed for getting along with others, negative behaviors such as aggression and lying, and respect and support for other family members (Deutsch, 2005; Falbo & Poston, 1993; Fuligni & Zhang, 2004; Poston & Falbo, 1990). The difference between the early and later findings may be due to a change in parents’ behaviors toward only children as one-child families have become more common and expected, with the consequence that onlies are less likely to be spoiled.

469

The one-child policy in China is a good example of how the structure of families can change and of how, consistent with Bronfenbrenner’s model discussed in Chapter 9, the larger world affects what goes on within families. Culture, as well as social and economic events, can have a tremendous effect on the structure of families and interactions among family members. In industrialized Western societies as well, a variety of social changes in the past 50 years have had marked effects on the structure of the family. For example, families are smaller than in the past, and many more people are choosing to have children outside of wedlock. In addition, it is not uncommon today for children to be reared by one biological parent or to live in a family that has experienced one or more divorces (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2011). Such changes in the family can affect the resources available to the child, as well as the parents’ child-rearing practices and behavior.

In this chapter, we examine many developmental aspects of family interaction, including the ways in which parents’ approach to parenting can influence their children’s development, the ways in which children can influence their parents’ parenting, and the ways in which siblings may influence one another. In addition, we consider how family functioning and children’s development may have been affected by certain social changes that have occurred in the United States over the past seven decades—from the increased age of first-time parenthood to increased rates of divorce, remarriage, and maternal employment. We will also consider the impact that factors such as poverty and culture may have on developmental outcomes.

CULTURA CREATIVE/ALAMY

As you will see, the theme of nature and nurture is central to the study of the role of the family because a child’s heredity and rearing influence each other and jointly affect the child’s development. In addition, the theme of the active child is evident in our discussion of how children influence the way their parents socialize them. The theme of sociocultural context is also key, in that parenting practices are strongly influenced by cultural beliefs, biases, and goals and are related to different outcomes for children in different cultures. Furthermore, the issue of individual differences is a major theme in this chapter because different styles of parenting, child-rearing practices, and family structures are associated with differences in children’s social and emotional functioning. Finally, because parenting influences the quality of children’s day-to-day experience, as well as children’s beliefs and behaviors, understanding patterns of family functioning has relevance for our theme of research and children’s welfare.

470