338

Theories of Social Development

339

- Psychoanalytic Theories

- View of Children’s Nature

- Central Developmental Issues

- Freud’s Theory of Psychosexual Development

- Erikson’s Theory of Psychosocial Development

- Current Perspectives

- Review

- Learning Theories

- View of Children’s Nature

- Central Developmental Issues

- Watson’s Behaviorism

- Skinner’s Operant Conditioning

- Social Learning Theory

- Box 9.1: A Closer Look Bandura and Bobo

- Current Perspectives

- Review

- Theories of Social Cognition

- View of Children’s Nature

- Central Developmental Issues

- Selman’s Stage Theory of Role Taking

- Dodge’s Information-Processing Theory of Social Problem Solving

- Dweck’s Theory of Self-Attributions and Achievement Motivation

- Current Perspectives

- Review

- Ecological Theories of Development

- View of Children’s Nature

- Central Developmental Issues

- Ethological and Evolutionary Theories

- The Bioecological Model

- Box 9.2: Individual Differences Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- Box 9.3: Applications Preventing Child Abuse

- Current Perspectives

- Review

- Chapter Summary

340

Themes

Nature and Nurture

Nature and Nurture

The Active Child

The Active Child

Continuity/Discontinuity

Continuity/Discontinuity

Mechanisms of Change

Mechanisms of Change

The Sociocultural Context

The Sociocultural Context

Individual Differences

Individual Differences

Research and Children’s Welfare

Research and Children’s Welfare

magine yourself interacting face-to-face with an infant. What would it be like? You naturally smile and speak in an affectionate tone of voice, and the infant probably smiles and makes happy sounds back at you. If for some reason you speak in a loud, harsh voice, the baby becomes quiet and wary. If you look off to the left, the infant follows your gaze, as though assuming there is something interesting to see in that direction. Of course, the baby does not just respond to what you do; the baby also engages in independent behaviors, examining various objects or events in the room or maybe fussing for no obvious reason. Your interaction with the baby evokes emotions in you—joy, affection, frustration, and so on. Over time, through repeated interactions, you and the infant learn about each other and smile and vocalize more readily to each other than to someone else.

magine yourself interacting face-to-face with an infant. What would it be like? You naturally smile and speak in an affectionate tone of voice, and the infant probably smiles and makes happy sounds back at you. If for some reason you speak in a loud, harsh voice, the baby becomes quiet and wary. If you look off to the left, the infant follows your gaze, as though assuming there is something interesting to see in that direction. Of course, the baby does not just respond to what you do; the baby also engages in independent behaviors, examining various objects or events in the room or maybe fussing for no obvious reason. Your interaction with the baby evokes emotions in you—joy, affection, frustration, and so on. Over time, through repeated interactions, you and the infant learn about each other and smile and vocalize more readily to each other than to someone else.

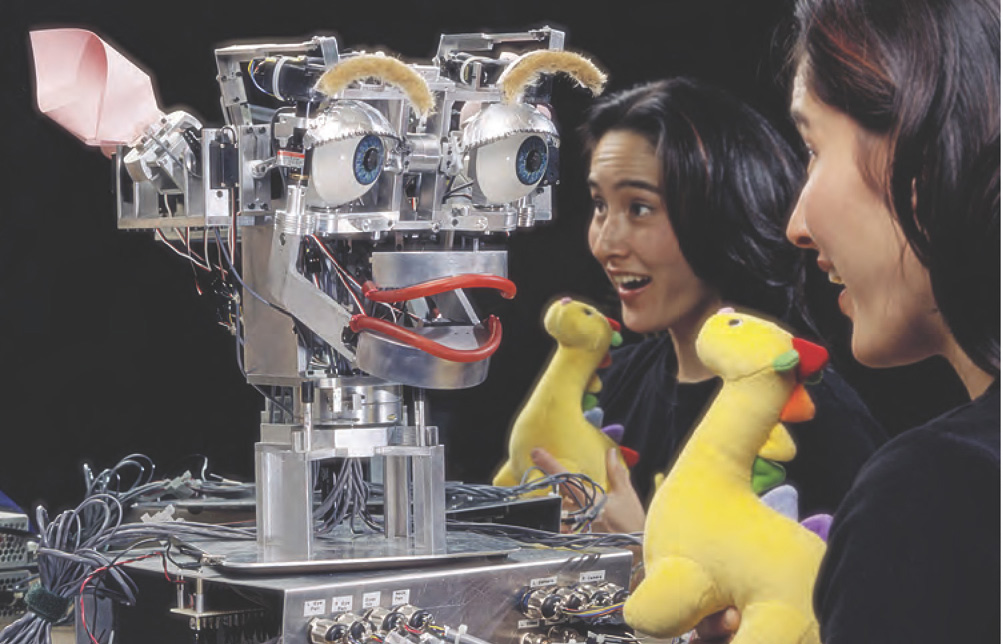

Now, imagine that you are asked to interact with Kismet, the robot pictured below, just as you would with a human infant. Although the request might seem strange, Kismet’s facelike features make you willing to give it a try. So you smile and speak in an affectionate tone—“Hi, Kismet, how are you?” Kismet smiles back at you and gurgles happily. You speak harshly, “Kismet, stop that right now.” The robot looks surprised—even a bit frightened—and makes a whimpering sound. You find yourself spontaneously attempting to console Kismet: “I’m sorry; I didn’t mean it.” After just a few moments, you have lost your feeling of self-consciousness and find the interaction with your new metallic friend remarkably natural. You may even start to feel fond of Kismet.

Kismet exists, and the robot’s behavior is pretty much as we have just described it. One of the world’s first “social robots,” Kismet was designed by a team of scientists headed by Cynthia Breazeal. Their primary goal was to develop robots that, instead of being programmed to behave in specific ways, are programmed to learn from their social interactions with humans, just as infants do. Accordingly, they designed Kismet as a sociable, “cute” infantlike robot that could elicit the attention of, and “nurturing” from, humans. Kismet’s behavior is readily interpretable in human terms, and the robot even seems to have internal mental and emotional states and a personality. Kismet learns from its interactions with people—from the instructions it receives from them and from their reactions to its behavior. Through these interactions with others, Kismet figures out how to interpret facial expressions, how to communicate, what behaviors are acceptable and unacceptable, and so on. Thus, Kismet develops over time as a function of the interaction between the “innate” structure built into it and its subsequent socially mediated experience. Just like a baby!

341

The challenge for Kismet’s designers was in many ways like the task of developmental scientists who attempt to account for how children’s development is shaped through their interactions with other people. Any successful account of social development must include the many ways we influence one another, starting with the simple fact that no human infant can survive without intensive, long-term care by other people. We learn how to behave on the basis of how others respond to our behavior; we learn how to interpret ourselves according to how others treat us; and we interpret other people by analogy to ourselves—all in the context of social interaction and human society. Over the past few years, Kismet’s designers, as well other pioneers in the field, have made important strides in their efforts to allow their increasingly more sophisticated robot infants to develop and learn from others. Indeed, some researchers predict that within a few years, they will have developed cyberbabies that can acquire the cognitive and social abilities of a typical 3-year-old human child.

In this chapter, we review some of the most important and influential general theories of social development, theories that attempt to account for how children’s development is affected by the people and social institutions around them. In our survey of cognitive theories in Chapter 4, we discussed some of the reasons why theories are important; those reasons apply equally well to theories of social development.

Theories of social development attempt to account for many important aspects of development, including emotion, personality, attachment, self, peer relationships, morality, and gender. In this chapter, we will describe four types of theories that address these topics, reflecting, in turn, the psychoanalytic, learning, social cognitive, and ecological perspectives. We will discuss the basic tenets of each theory and examine some of the relevant evidence.

Every one of our seven themes appears in this chapter, with three of them being particularly prominent. The theme that pervades this chapter most extensively is individual differences, as we examine how the social world differentially affects children’s development. The theme of nature and nurture helps us to distinguish between the theories, because they vary in the degree to which they emphasize biological and environmental factors. The active child theme is also a major focus: some of the theories emphasize children’s active participation in, and effect on, their own socialization, whereas others view children’s development as shaped primarily by external forces.