Psychoanalytic Theories

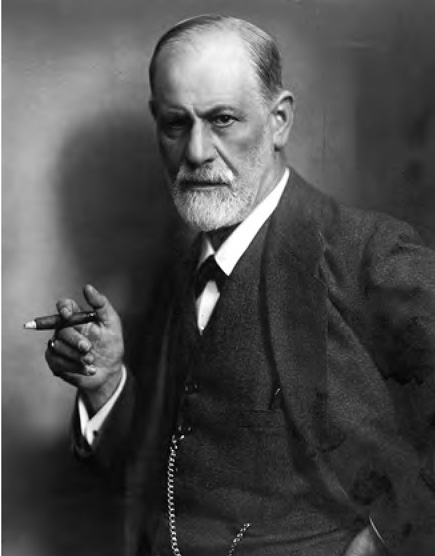

No psychological theory has had a greater impact on Western culture and on thinking about personality and social development than the psychoanalytic theory of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). A successor to Freud’s theory, the life-span developmental theory of Erik Erikson (1902–1994), has also been quite influential.

342

View of Children’s Nature

In both Freud’s and Erikson’s theories, development is largely driven by biological maturation. For Freud, behavior is motivated by the need to satisfy basic drives. These drives, and the motives that arise from them, are mostly unconscious, and individuals often have only the dimmest understanding of why they do what they do. In Erikson’s theory, development is driven by a series of developmental crises related to age and biological maturation. To achieve healthy development, the individual must successfully resolve these crises.

Central Developmental Issues

Three of our seven themes—continuity/discontinuity, individual differences, and nature and nurture—play prominent roles in psychoanalytic theory. Like Piaget’s theory of cognitive development that you encountered in Chapter 4, the developmental accounts of Freud and Erikson are stage theories. However, within the framework of discontinuous development, psychoanalytic theories stress the continuity of individual differences, emphasizing that children’s early experiences have a major impact on their subsequent development. The interaction of nature and nurture arises in terms of Freud and Erikson’s emphasis on the biological underpinnings of developmental stages and how they interact with the child’s experience.

Freud’s Theory of Psychosexual Development

Freud began his career as a neurologist and soon became interested in the origins and treatment of mental illness. He was particularly intrigued by the fact that sometimes his patients’ symptoms—such as loss of feeling in a hand or blindness—had no apparent physical cause. After listening to his patients talk about their problems, he came to the conclusion that these unexplained symptoms could be attributed to completely unconscious but powerful feelings of guilt, anxiety, or fear—such as the fear of touching or seeing something forbidden. Freud’s interest in psychological development grew as he became increasingly convinced that the majority of his patients’ emotional problems originated in their early childhood relationships, particularly those with their parents. Freud made fundamental, lasting contributions to developmental psychology, although, as we will discuss later, they had to do with certain broad psychological concepts, not with the specifics of his theory.

In our discussion of Freud’s theoretical views, we will focus primarily on their developmental aspects, especially the broad themes that remain influential today.

Basic Features of Freud’s Theory

psychic energy  Freud’s term for the collection of biologically based instinctual drives that he believed fuel behavior, thoughts, and feelings

Freud’s term for the collection of biologically based instinctual drives that he believed fuel behavior, thoughts, and feelings

Freud’s theory of development is referred to as a theory of psychosexual development because he thought that even very young children have a sexual nature that motivates their behavior and influences their relationships with other people. He proposed that children pass through a series of universal developmental stages. According to Freud, in each successive stage, psychic energy—the biologically based, instinctual drives that fuel behavior, thoughts, and feelings—becomes focused in different erogenous zones, that is, areas of the body that are erotically sensitive (e.g., the mouth, the anus, and the genitals). Freud believed that in each stage, children encounter conflicts related to a particular erogenous zone, and he maintained that their success or failure in resolving these conflicts affects their development throughout life.

343

The Developmental Process

erogenous zones  in Freud’s theory, areas of the body that become erotically sensitive in successive stages of development

in Freud’s theory, areas of the body that become erotically sensitive in successive stages of development

In Freud’s view, development starts with a helpless infant beset by instinctual drives, foremost among them hunger, which creates tension. The young infant has no knowledge of how to reduce it, so the distress associated with hunger is expressed through crying, prompting the mother to breast-feed the baby. (In Freud’s day, virtually all babies were breast-fed.) The resulting satisfaction of the infant’s hunger, as well as the experience of nursing, is a source of intense pleasure for the infant.

id  in psychoanalytic theory, the earliest and most primitive personality structure. It is unconscious and operates with the goal of seeking pleasure.

in psychoanalytic theory, the earliest and most primitive personality structure. It is unconscious and operates with the goal of seeking pleasure.

The instinctual drives with which the infant is born constitute the id—the earliest and most primitive of three personality structures posited by Freud. The id, which is totally unconscious, is the source of psychic energy. It is the “dark, inaccessible part of our personality…a cauldron full of seething excitations” in need of satisfaction (Freud, 1933/1964). The id is ruled by the pleasure principle—the goal of achieving maximal gratification maximally quickly. Whether the gratification involves eating, drinking, eliminating, or physical comfort, the id wants it now. The id remains the source of psychic energy throughout life, with its operation most apparent in selfish or impulsive behavior in which immediate gratification is sought with little regard for consequences.

oral stage  the first stage in Freud’s theory, occurring in the first year, in which the primary source of satisfaction and pleasure is oral activity

the first stage in Freud’s theory, occurring in the first year, in which the primary source of satisfaction and pleasure is oral activity

During the first year of life, the infant is in Freud’s first stage of psychosexual development, the oral stage, so called because the primary source of gratification and pleasure is oral activity, such as sucking and eating. “If the infant could express itself, it would undoubtedly acknowledge that the act of sucking at its mother’s breast is far and away the most important thing in life” (Freud, 1920/1965). The pleasure associated with breast-feeding is so intense that other oral activities—sucking on a thumb or pacifier, for instance—also provide pleasure.

For Freud, the baby’s feelings for his or her mother are “unique, without parallel,” and through them the mother is “established unalterably for a whole lifetime as the first and strongest love-object and as the prototype for all later love-relations” (1940/1964).

The infant’s mother is also a source of security. However, this security does not come without costs. As always with Freud, there is a dark side: infants “pay for this security by a fear of loss of love” (Freud, 1940/1964). For Freud, common fearful reactions to being alone or in the dark are based on “missing someone who is loved and longed for” (1926/1959).

ego  in psychoanalytic theory, the second personality structure to develop. It is the rational, logical, problem-solving component of personality.

in psychoanalytic theory, the second personality structure to develop. It is the rational, logical, problem-solving component of personality.

Later in the first year, the second personality structure, the ego, begins to emerge. It arises out of the need to resolve conflicts between the id’s unbridled demands for immediate gratification and the restraints imposed by the external world. Whereas “the id stands for the untamed passions,” the ego “stands for reason and good sense” (1933/1964). The ego operates under the reality principle, trying to find ways to satisfy the id that accord with the demands of the real world. Over time, as it continually seeks resolution between the demands of the id and those of the real world, the ego begins to develop into the individual’s sense of self. Nevertheless, the ego is never fully in control:

The ego’s relation to the id might be compared with that of a rider to his horse. The horse supplies the locomotive energy, while the rider has the privilege of deciding on the goal and of guiding the powerful animal’s movement. But only too often…the rider [is] obliged to guide the horse along the path by which it itself wants to go.

(Freud, 1933/1964, p. 77)

anal stage  the second stage in Freud’s theory, lasting roughly from + to × years of age, in which the primary source of pleasure comes from defecation

the second stage in Freud’s theory, lasting roughly from + to × years of age, in which the primary source of pleasure comes from defecation

During the infant’s second year, maturation facilitates the development of control over some bodily processes, including urination and defecation. At this point, the infant enters Freud’s second stage, the anal stage, which lasts until roughly age 3. In this stage, the child’s erotic interests focus on the pleasurable relief of tension derived from defecation. Conflict ensues when, for the first time, the parents begin to make specific demands on the infant, most notably their insistence on toilet training. In the years to come, parents and others will increase their demands on the child to control his or her impulses and to delay gratification.

344

phallic stage  the third stage in Freud’s theory, lasting from age × to age 6, in which sexual pleasure is focused on the genitalia

the third stage in Freud’s theory, lasting from age × to age 6, in which sexual pleasure is focused on the genitalia

Freud’s third stage of development, the phallic stage, spans the ages of 3 to 6. In this stage, the focus of sexual pleasure again migrates, as children become interested in their own genitalia and curious about those of parents and playmates. Both boys and girls derive pleasure from masturbation, an activity that the parents of Freud’s time and place often punished severely.

superego  in psychoanalytic theory, the third personality structure, consisting of internalized moral standards

in psychoanalytic theory, the third personality structure, consisting of internalized moral standards

Freud believed that during the phallic stage, children identify with their same-sex parent, giving rise to gender differences in attitudes and behavior. This identification begins with children’s discovery of the vital difference between having and lacking a penis. At this time, a boy takes a strong interest in his penis, “so easily excitable and changeable, and so rich in sensations” (Freud, 1923/1960, p. 246). Freud supposed that girls notice and resent the fact that they do not have one, experiencing what he called penis envy.

internalization  the process of adopting as one’s own the attributes, beliefs, and standards of another person

the process of adopting as one’s own the attributes, beliefs, and standards of another person

Freud also believed that young children experience intense sexual desires during the phallic stage, and he proposed that their efforts to cope with them leads to the emergence of the third personality structure, the superego. The superego is essentially what we think of as conscience. It enables a child to control his or her own behavior on the basis of beliefs about right and wrong. The superego is based on the child’s internalization, or adoption, of the parents’ rules and standards for acceptable and unacceptable behavior. The superego guides the child to avoid actions that would result in guilt, which the child experiences when violating these internalized rules and standards.

Oedipus complex  Freud’s term for the conflict experienced by boys in the phallic period because of their sexual desire for their mother and their fear of retaliation by their father. (The complex is named for the king in Greek mythology who unknowingly murdered his father and married his mother.)

Freud’s term for the conflict experienced by boys in the phallic period because of their sexual desire for their mother and their fear of retaliation by their father. (The complex is named for the king in Greek mythology who unknowingly murdered his father and married his mother.)

For boys, the path to superego development is through the resolution of the Oedipus complex, a psychosexual conflict in which a boy experiences a form of sexual desire for his mother and wants an exclusive relationship with her. Although this idea may seem outlandish, many family stories are consistent with it. For example, when one of our sons was a 5-year-old, he told his mother that he wanted to marry her someday. She said that she was sorry, but she was already married to Daddy, so he would have to marry someone else. The boy replied, “I have a good idea. I’ll put Daddy in a big box and mail him away somewhere. Then we can get married!”

Electra complex  Freud’s term for the conflict experienced by girls in the phallic stage when they develop unacceptable romantic feelings for their father and see their mother as a rival. (The complex is named after a figure in Greek mythology who arranged for the murder of her mother.)

Freud’s term for the conflict experienced by girls in the phallic stage when they develop unacceptable romantic feelings for their father and see their mother as a rival. (The complex is named after a figure in Greek mythology who arranged for the murder of her mother.)

In Freud’s account of the Oedipal conflict, the son’s desire for his mother and his hostility toward his father are highly threatening. In response, the boy’s ego protects him through repression, banishing his dangerous feelings to the unconscious, the mental storehouse where anxiety-producing thoughts and impulses are held hidden from conscious awareness. A consequence of this widespread repression, according to Freud, is infantile amnesia—the lack of memories from our first few years that we all suffer. In addition, the boy increases his identification with his father: through striving to be like him, the boy internalizes his father’s values, beliefs, and attitudes, leading to the development of a strong conscience. Freud thought that girls experience a similar but less intense conflict—the Electra complex, involving erotic feelings toward the father—which results in their developing a weaker conscience than boys do.

345

latency period  the fourth stage in Freud’s theory, lasting from age 6 to age 12, in which sexual energy gets channeled into socially acceptable activities

the fourth stage in Freud’s theory, lasting from age 6 to age 12, in which sexual energy gets channeled into socially acceptable activities

The fourth developmental stage, the latency period, lasts from about age 6 to age 12. It is, as its name implies, a time of relative calm. Sexual desires are safely hidden away in the unconscious, and psychic energy gets channeled into constructive, socially acceptable activities, including both intellectual and social pursuits.

The fifth and final stage, the genital stage, begins with the advent of sexual maturation. The sexual energy that had been kept in check for several years reasserts itself with full force, although it is now, for the majority of individuals, directed toward other-sex peers. Ideally, the individual has developed a strong ego that facilitates coping with reality and a superego that is neither too weak nor too strong.

genital stage  the fifth and final stage in Freud’s theory, beginning in adolescence, in which sexual maturation is complete and sexual intercourse becomes a major goal

the fifth and final stage in Freud’s theory, beginning in adolescence, in which sexual maturation is complete and sexual intercourse becomes a major goal

Freud thought that healthy development culminates in the ability to invest oneself in, and derive pleasure from, both love and work. This outcome can be compromised in many ways, however. If fundamental needs are not met during any of the stages of psychosexual development, children may become fixated on those needs, continually attempting to satisfy them and to resolve associated conflicts. In Freud’s view, these unsatisfied needs, and the person’s ongoing attempts to fulfill them, are unconscious and are expressed in indirect or symbolic ways. For example, if an infant’s needs for oral gratification are not adequately satisfied during the oral stage, later in life the individual may repeatedly engage in substitute oral activities, such as excessive eating, nail-biting, smoking, and so on. Similarly, if toddlers are subjected to very harsh toilet training during the anal stage, they may remain preoccupied with issues related to cleanliness, becoming compulsively tidy and psychologically rigid or extremely sloppy and lax. Thus, in Freud’s view, the nature of the child’s passage through the stages of psychosexual development shapes the individual’s personality for life. (With regard to oral and anal fixations, it is interesting that Freud smoked 20 cigars a day for more than 50 years—in fact, he found it impossible to work without them—and over the same period followed the same ritualized schedule nearly every day.)

Erikson’s Theory of Psychosocial Development

Of the many followers of Freud, none has had greater influence in developmental psychology than Erikson. Erikson accepted the basic elements of Freud’s theory but incorporated social factors into it, including cultural influences and contemporary issues, such as juvenile delinquency, changing sexual roles, and the generation gap. Consequently, his theory is regarded as a theory of psychosocial development.

The Developmental Process

Erikson proposed eight age-related stages of development that span infancy to old age. Each of Erikson’s stages is characterized by a specific crisis, or set of developmental issues, that the individual must resolve. If the dominant issue of a given stage is not successfully resolved before the onset of the next stage, the person will continue to struggle with it. In the following summary of Erikson’s stages, we discuss only the first five stages, which focus on development in infancy, childhood, and adolescence.

346

- Basic Trust Versus Mistrust (the first year). In Erikson’s first stage (which corresponds to Freud’s oral stage), the crucial issue for the infant is developing a sense of trust—“an essential trustfulness of others as well as a fundamental sense of one’s own trustworthiness” (Erikson, 1969, p. 96). If the mother is warm, consistent, and reliable in her caregiving, the infant learns that she can be trusted. More generally, the baby comes to feel good and reassured by being close to other people. If the ability to trust others when it is appropriate to do so does not develop, the person will have difficulty forming intimate relationships later in life.

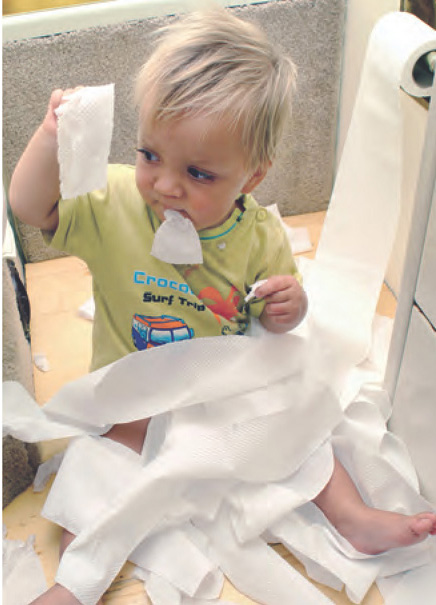

- Autonomy Versus Shame and Doubt (ages 1 to 3½). The challenge for the child between ages 1 year and 3½ years (Freud’s anal stage) is to achieve a strong sense of autonomy while adjusting to increasing social demands. Going well beyond Freud’s focus on toilet training, Erikson pointed out that during this period, the dramatic increases that occur in every realm of children’s real-world competence—including motor skills, cognitive abilities, and language—foster children’s desires to make choices and decisions for themselves. Infants’ newfound ability to explore the environment on their own (as we discussed in Chapter 5) changes the family dynamics, initiating a long-running battle of wills in which parents try to restrict the child’s freedom and teach the child which behaviors are acceptable and unacceptable. If parents provide a supportive atmosphere that allows children to achieve self-control without the loss of self-esteem, children gain a sense of autonomy. In contrast, if children are subjected to severe punishment or ridicule, they may come to doubt their abilities or to feel a general sense of shame.

Many parents witness scenes like the one depicted here. Should this toddler be made to feel shame for his natural exploratory behavior?INEART/ALAMY

Many parents witness scenes like the one depicted here. Should this toddler be made to feel shame for his natural exploratory behavior?INEART/ALAMY - Initiative Versus Guilt (ages 4 to 6). Like Freud, Erikson saw the time between ages 4 and 6 years as a period during which children come to identify with, and learn from, their parents: “[The child] hitches his wagon to nothing less than a star: he wants to be like his parents, who to him appear very powerful and very beautiful” (Erikson, 1959/1994). The child in this third stage of development is constantly setting goals (building a high tower of blocks, learning the alphabet) and working to achieve them. Like Freud, Erikson believed that a crucial attainment is the development of conscience—the internalization of the parents’ rules and standards, and the experiencing of guilt when failing to uphold them. The challenge for the child is to achieve a balance between initiative and guilt. If parents are not highly controlling or punitive, children can develop high standards and the initiative to meet them without being crushed by worry about not being able to measure up.

- Industry Versus Inferiority (age 6 to puberty). Erikson’s fourth stage, which lasts from age 6 to puberty (Freud’s latency period), is crucial for ego development. During this stage, children master cognitive and social skills that are important in their culture, and they learn to work industriously and to cooperate with peers. Successful experiences give the child a sense of competence, but failure can lead to excessive feelings of inadequacy or inferiority.

- Identity Versus Role Confusion (adolescence to early adulthood). Erikson accorded great importance to adolescence, seeing it as a critical stage for the achievement of a core sense of identity. Adolescents change so rapidly in so many ways that they can hardly recognize themselves, either in the mirror or in their minds. The dramatic physical changes of puberty and the emergence of strong sexual urges are accompanied by new social pressures, including a need to make educational and occupational decisions. Caught between their past identity as a child and the many options and uncertainties of their future, adolescents must resolve the question of who they really are or live in confusion about what roles they should play as adults. As you will see in Chapter 11, developmental scientists have devoted a good deal of attention to the stage of identity versus role confusion in modern multicultural societies.

347

Current Perspectives

The most significant of Freud’s contributions to developmental psychology were his emphasis on the importance of early experience and emotional relationships and his recognition of the role of subjective experience and unconscious mental activity. Erikson’s emphasis on the quest for identity in adolescence has had a lasting impact, providing the foundation for a wealth of research on this aspect of adolescence. The signal weakness of both theories is that their major theoretical claims are stated too vaguely to be testable, and many of their specific elements, particularly in Freud’s theory, are generally regarded as highly questionable. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that Freud’s theory has been enormously influential. Furthermore, in recent years, some of Freud’s and Erikson’s original ideas have reemerged in modified form in psychological research and thinking.

Freud’s identification of infantile amnesia, for example, has been supported by a vast literature on the earliest memories that people can recall (Bauer, Wenner, & Kroupina, 2002; Hayne, 2004; Neisser, 2004). Freud was correct in noting that few of us have conscious memories of our experiences from our first few years. However, although the precise reasons for the absence of autobiographical memory in the first three years are unknown, virtually no one thinks it is due to repression, as Freud claimed.

Erikson’s psychosocial stages of development have also received some support from research on autobiographical memory. In one study, adults between the ages of 62 and 89 were asked to recall up to three memories from each decade of their lives, and the researchers classified their reports with respect to Erikson’s stages (Conway & Holmes, 2004). The reported memories of these older adults corresponded quite well with Erikson’s stages. For example, memories from the second decade of their lives were predominantly of experiences having to do with identity confusion and establishing a sense of identity.

Freud’s emphasis on the importance of early experience and close relationships was especially influential in setting the foundation for modern-day attachment theory and research (which you will read about in Chapter 11). The research in this area strongly suggests that the nature of infants’ relationships with their parents not only affects behavior in infancy but also has important long-term effects on close relationships throughout life (Allen et al., 2004; Kobak, Cassidy, & Ziv, 2004; Main, 2000).

In addition, Freud’s remarkable insight that much of our mental life occurs outside the realm of consciousness is fundamental to modern cognitive psychology and brain science. Indeed, current research in cognitive and affective neuroscience suggests that a remarkably large proportion of human behavior stems from unconscious processes. According to this research, we are, to a surprising degree, “strangers to ourselves,” often acting on the basis of unconscious processes and only later constructing rational accounts of our behavior (T. D. Wilson, 2002). In this sense, we experience the “illusion of conscious will,” believing that our thoughts are the basis for our behavior, even though those thoughts often come after the brain has already initiated the behavior (Wegner, 2002). Many of us cry out and jump back even before we are aware that there is a snake across our path (Öhman & Mineka, 2001).

348

Our behavior is also influenced by implicit attitudes of which we are unaware, attitudes that are often antithetical to what we consciously believe. For example, many individuals who believe that they lack racial prejudice nevertheless unconsciously associate members of some racial groups with a variety of negative characteristics (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995; Nosek & Banaji, 2009). Even children as young as 6 years of age exhibit implicit racial biases (Baron & Banaji, 2006). To experience this phenomenon first hand, visit http://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit and take the Implicit Attitudes Test: the result may surprise you (although it would probably not have surprised Freud).

How might psychoanalytic theories be useful to Kismet’s designers? They have already adopted the goal of making Kismet as sociable as possible. Probably the most important further step they can take, based on Freud’s and Erikson’s theories, is to program Kismet to form a few very close relationships with others. Certain people should become much more important to Kismet than other people with whom it interacts. Ideally, Kismet should derive some sense of security and well-being from those relationships. Furthermore, those relationships should have a lasting effect on Kismet’s internal organization so that they continue to influence the robot throughout its “life.”

review:

The psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud and Erik Erikson propose that social and emotional development proceeds in a series of stages, with each stage characterized by a particular task or crisis that must be resolved for subsequent healthy development. A healthy personality involves an appropriate balance between the three structures of personality—id, ego, and superego. Maturational factors play a key role in both theories. Psychic energy and sexual impulses are emphasized by Freud as major forces in development, whereas Erikson places greater emphasis on social factors. Both theories maintain that early experiences in the context of the family have a lasting effect on the individual’s relationships with other people. These theories have had enormous, continuing impact on Western thought and culture.