128

129

Theories of Cognitive Development

- Piaget’s Theory

- View of Children’s Nature

- Central Developmental Issues

- The Sensorimotor Stage (Birth to Age 2 Years)

- The Preoperational Stage (Ages 2 to 7)

- The Concrete Operational Stage (Ages 7 to 12)

- The Formal Operational Stage (Age 12 and Beyond)

- Piaget’s Legacy

- Box 4.1: Applications Educational Applications of Piaget’s Theory

- Review

- Information-Processing Theories

- View of Children’s Nature

- Central Developmental Issues

- Box 4.2: Applications Educational Applications of Information-Processing Theories

- Review

- Sociocultural Theories

- View of Children’s Nature

- Central Developmental Issues

- Box 4.3: Applications Educational Applications of Sociocultural Theories

- Review

- Dynamic-Systems Theories

- View of Children’s Nature

- Central Development Issues

- Box 4.4: Applications Educational Applications of Dynamic-Systems Theories

- Review

- Chapter Summary

130

Themes

Nature and Nurture

Nature and Nurture

The Active Child

The Active Child

Continuity/Discontinuity Mechanisms of Change

Continuity/Discontinuity Mechanisms of Change

The Sociocultural Context

The Sociocultural Context

Research and Children’s Welfare

Research and Children’s Welfare

7-month-old boy, sitting on his father’s lap, becomes intrigued with the father’s glasses, grabs one side of the frame, and yanks it. The father says, “Ow!” and his son lets go, but then reaches up and yanks the frame again. The father readjusts the glasses, but his son again grasps them and yanks. How, the father wonders, can he prevent his son from continuing this annoying routine without causing him to start screaming? Fortunately, the father, a developmental psychologist, soon realizes that Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development suggests a simple solution: put the glasses behind his back. According to Piaget’s theory, removing an object from a young infant’s sight should lead the infant to act as if the object never existed. The strategy works perfectly; after the father puts the glasses behind his back, his son shows no further interest in them and turns his attention elsewhere. The father silently thanks Piaget.

7-month-old boy, sitting on his father’s lap, becomes intrigued with the father’s glasses, grabs one side of the frame, and yanks it. The father says, “Ow!” and his son lets go, but then reaches up and yanks the frame again. The father readjusts the glasses, but his son again grasps them and yanks. How, the father wonders, can he prevent his son from continuing this annoying routine without causing him to start screaming? Fortunately, the father, a developmental psychologist, soon realizes that Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development suggests a simple solution: put the glasses behind his back. According to Piaget’s theory, removing an object from a young infant’s sight should lead the infant to act as if the object never existed. The strategy works perfectly; after the father puts the glasses behind his back, his son shows no further interest in them and turns his attention elsewhere. The father silently thanks Piaget.

This experience, which one of us actually had, illustrates in a small way how understanding theories of child development can yield practical benefits. It also illustrates three broader advantages of knowing about such theories:

1. Developmental theories provide a framework for understanding important phenomena. Theories help to reveal the significance of what we observe about children, both in research studies and in everyday life. Someone who witnessed the glasses incident but who did not know about Piaget’s theory might have found the experience amusing but insignificant. Seen in terms of Piaget’s theory, however, this passing event exemplifies a general and profoundly important developmental phenomenon: infants younger than 8 months react to the disappearance of an object as though they do not understand that the object still exists. In this way, theories of child development place particular experiences and observations in a larger context and deepen our understanding of their meaning.

2. Developmental theories raise crucial questions about human nature. Piaget’s theory about young infants’ reactions to disappearing objects was based on his informal experiments with infants younger than 8 months. Piaget would cover one of their favorite objects with a cloth or otherwise put it out of sight and then wait to see whether the infants tried to retrieve the object. They rarely did, leading Piaget to conclude that before the age of 8 months, infants do not realize that hidden objects still exist. Other researchers have challenged this explanation. They argue that infants younger than 8 months do in fact understand that hidden objects continue to exist but lack the memory or problem-solving skills necessary for using that understanding to retrieve hidden objects (Baillargeon, 1993). Despite these disagreements about how best to interpret young infants’ failure to retrieve hidden objects, researchers agree that Piaget’s theory raises a crucial question about human nature: Do infants realize from the first days of life that objects continue to exist when out of sight, or is this something that they learn later? More significant, do young infants understand that people continue to exist when they cannot be seen? Do they fear that Mom no longer exists when she disappears from sight?

3. Developmental theories lead to a better understanding of children. Theories also stimulate new research that may support the theories’ claims, fail to support them, or require refinements of them, thereby improving our understanding of children. For example, Piaget’s ideas led Munakata and her colleagues (1997) to test whether 7-month-olds’ failure to reach for hidden objects was due to their lacking the motivation or the reaching skill to retrieve them. To find out, the researchers created a situation similar to Piaget’s object-permanence experiment, except that they placed the object, an attractive toy, under a transparent cover rather than under an opaque one. In this situation, infants quickly removed the cover and regained the toy. This finding seemed to support Piaget’s original interpretation by showing that neither lack of motivation nor lack of ability to reach for the toy explained the infants’ usual failure to retrieve it.

131

In contrast, an experiment conducted by Diamond (1985) indicated a need to revise Piaget’s theory. Using an opaque covering, as Piaget did, Diamond varied the amount of time between when the toy was hidden and when the infant was allowed to reach for it. She found that even 6-month-olds could locate the toy if allowed to reach immediately, that 7-month-olds could wait as long as 2 seconds and still succeed, that 8-month-olds could wait as long as 4 seconds and still succeed, and so on. Diamond’s finding indicated that memory for the location of hidden objects, as well as the understanding that they continue to exist, is crucial to success on the task. In sum, theories of child development are useful because they provide frameworks for understanding important phenomena, raise fundamental questions about human nature, and motivate new research that increases understanding of children.

Because child development is such a complex and varied subject, no single theory accounts for all of it. The most informative current theories focus primarily on either cognitive development or social development. Providing a good theoretical account of development in even one of these areas is an immense challenge, because each of them spans a huge range of topics. Cognitive development includes the growth of such diverse capabilities as perception, attention, language, problem solving, reasoning, memory, conceptual understanding, and intelligence. Social development includes the growth of equally diverse areas: emotions, personality, relationships with peers and family members, self-understanding, aggression, and moral behavior. Given this immense range of developmental domains, it is easy to understand why no one theory has captured the entirety of child development.

Therefore, we present cognitive and social theories in separate chapters. We consider theories of cognitive development in this chapter, just before the chapters on specific areas of cognitive development, and consider theories of social development in Chapter 9, just before the chapters on specific areas of social development.

This chapter examines four theoretical perspectives on cognitive development that are particularly influential: the Piagetian perspective, the information-processing perspective, the sociocultural perspective, and the dynamic-systems perspective. We consider each perspective’s fundamental assumptions about children’s nature, the central developmental issues on which the perspective focuses, and practical examples of the perspective’s usefulness for helping children learn.

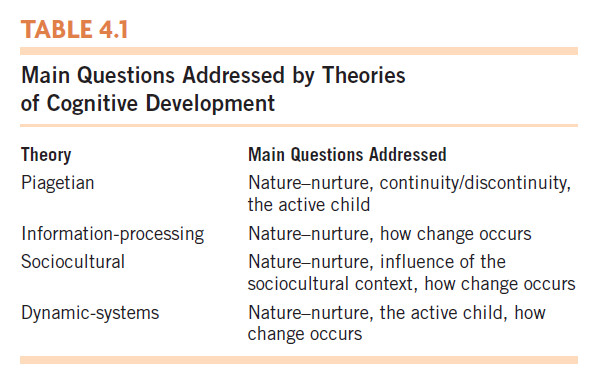

These four theoretical perspectives are influential in large part because they provide important insights into the basic developmental themes described in Chapter 1. Each perspective addresses all the themes to some extent, but each emphasizes different ones. For example, Piaget’s theory focuses on continuity/discontinuity and the active child, whereas information-processing theories focus on mechanisms of change (Table 4.1). Together, the four perspectives allow a broader appreciation of cognitive development than any one of them does alone.