Ecological Theories of Development

We now turn to a set of theories united by the fact that they take a very broad view of the context of social development. Virtually all psychological theories, and certainly those that we have reviewed in the chapter thus far, emphasize the role of the environment in the development of individual children. However, the “environment” in many of these theories is narrowly construed as immediate contexts—family, peers, schools. The first two approaches discussed here—ethological and evolutionary psychology views—relate children’s development to the grand context of the evolutionary history of our species. The third approach—the bioecological model—considers multiple levels of environmental influence that simultaneously affect development.

View of Children’s Nature

Ethological and evolutionary theories view children as inheritors of genetically based abilities and predispositions. The focus of these theories is largely on aspects of behavior that serve, or once served, an adaptive function.

The bioecological model stresses the effects of context on development, but it also emphasizes the child’s active role in selecting and influencing those contexts. Children’s personal characteristics—temperament, intellectual ability, athletic skill, and so on—lead them to choose certain environments over others, and also influence the people around them.

Central Developmental Issues

The developmental issue that is front and center in ecological theories is the interaction of nature and nurture. The importance of the sociocultural context and the continuity of development are implicitly emphasized in all these theories. The active role of children in their own development is another central focus, primarily of the bioecological approach.

Ethological and Evolutionary Theories

Ethological and evolutionary theories are concerned with understanding various aspects of development and behavior in terms of a given animal’s evolutionary heritage. Of particular interest are species-specific behaviors—behaviors that are common to members of a particular species (such as humans) but not typically observed in other species.

Ethology

ethology  the study of the evolutionary bases of behavior

the study of the evolutionary bases of behavior

Ethology, the study of behavior within an evolutionary context, attempts to understand behavior in terms of its adaptive or survival value. According to ethologists, a variety of innate behavior patterns in animals were shaped by evolution just as surely as their physical characteristics were (Crain, 1985).

363

imprinting  a form of learning in which the young of some species of newborn birds and mammals become attached to and follow adult members of the species (usually their mother)

a form of learning in which the young of some species of newborn birds and mammals become attached to and follow adult members of the species (usually their mother)

Ethological approaches have frequently been applied to developmental issues. The prototypical, and best-known, example is the study of imprinting made famous by Konrad Lorenz (1903–1989), who is often referred to as the father of modern ethology (Lorenz, 1935, 1952). Imprinting is a process by which newborn birds and mammals of some species become attached to their mother at first sight and follow her everywhere, a behavior that ensures that the baby will stay near a source of protection and food. For imprinting to occur, the infant has to encounter its mother during a specific critical period very early in life.

The basis for imprinting is not actually the baby’s mother per se; rather, the infants of some species are genetically predisposed to follow around the first moving object with particular characteristics that they see after emerging into the world. In chickens, for example, imprinting is elicited specifically by the sight of a bird’s head and neck regions (M. H. Johnson, 1992). Which particular object the individual will dutifully trail after is thus a matter of experience-expectant processes (discussed in Chapter 3, pages 115–116). Usually, the first moving object any chick sees is its mother, so everything works out just fine.

Although human newborns do not “imprint,” they do have strong tendencies that draw them to members of their own species. Examples noted in Chapter 5 include an innate visual preference for faces, which seems to result from an attraction to a face shape with more “stuff” in the top half. Even though this attraction is not based on a specific human face template, it gets the infant to pay attention to the most significant entities in the environment. Also, like other mammals, human newborns orient to sounds, tastes, and smells familiar from their experience in the womb—a predisposition that inclines them toward their own mother (see Chapter 5). One of the most influential applications of ethology to human development, which we discuss in Chapter 11, is Bowlby’s (1969) extension of the concept of imprinting to the process by which infants form emotional attachments to their mother (pages 428–429).

Another example of human behavior to which an ethological perspective has been applied is the existence of differences in the play preferences of males and females (which you will read more about in Chapter 15). For example, many (but not all) boys prefer to play with vehicle toys (trucks and cars, for example), which afford action play, whereas girls prefer dolls, which are conducive to nurturant play. The standard accounts for these differences, which come from social learning and social cognitive theories, maintain that children (especially boys) are encouraged by their parents to play with “gender-appropriate” toys, and they do so because they want to be like others of their own sex.

However, some searchers argue that these accounts are not the whole story and that evolved predispositions fuel these preferences. In one study, for example, newborn girls looked longer at social stimuli—human faces—than at nonsocial stimuli such as mobiles, whereas the reverse was true for boys (Connellan et al., 2001). Similarly, 1-year-old boys watched a video of moving cars for longer than they watched a video of an active human face, whereas girls did the opposite (Lutchmaya & Baron-Cohen, 2002).

Evolutionary Psychology

A relatively new branch of psychology that is closely related to ethology is evolutionary psychology, which applies the Darwinian concepts of natural selection and adaptation to human behavior (Bjorklund, 2007; Geary, 2009). The basic idea of this approach is that in the evolutionary history of our species, certain genes predisposed individuals to behave in ways that solved the adaptive challenges they faced (obtaining food, avoiding predators, establishing social bonds), thereby increasing the likelihood that they would survive, mate, and reproduce, passing along their genes to their offspring. These adaptive genes became increasingly common and were passed down to modern humans; thus, many of the ways we behave today are a legacy from our prehistoric ancestors (Geary, 2009).

364

PICTURE PARTNERS/ALAMY

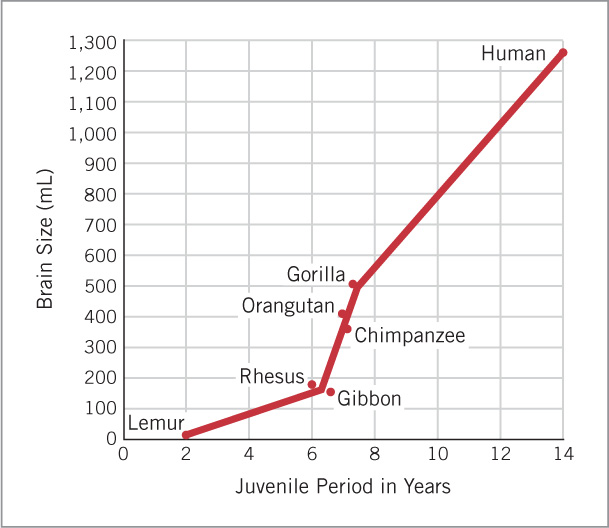

One of the most important adaptive features of the human species—one that clearly distinguishes us from other species—is the large size of our brains (relative to body size). The trade-off for this is the prolonged period of immaturity and dependence human children go through. We are “a slow-developing, big-brained species” (Bjorklund & Pellegrini, 2002), as illustrated in Figure 9.2. In Chapter 2, we discussed how the size of the human brain at birth is limited by the size of the female pelvis. As modern humans evolved, enlargement of our brains was made possible by birth occurring at a more “premature” stage of development than is characteristic of other mammals. These evolutionary changes were made possible by increased social complexity, which is necessary for successful caregiving of extremely helpless offspring. A related consequence of our large brains and slow development is our species-typical high level of neural plasticity that supports our unrivaled capacity for learning from experience. Highlighting the adaptive benefits of our extended immaturity, Bjorklund (1997) has pointed out that

a prolonged period of youth is necessary for humans [who,] more than any other species, must survive by their wits; human communities are more complex and diverse than those of any other species, and this requires that they have not only a flexible intelligence to learn the conventions of their societies but also a long time to learn them.

(p. 153, emphasis added)

Many evolutionary theorists have suggested that play, which is one of the most salient forms of behavior during the period of immaturity of most mammals, is an evolved platform for learning (Bjorklund & Pellegrini, 2002). Children develop motor skills by racing and wrestling with one another, throwing toy spears, or kicking a ball into a goal. They try out and practice a variety of social roles (as mentioned in Chapter 7), enacting what they know about being, say, a parent or a police officer. One of the main virtues of play is that children can experiment in a situation with minimal consequences; no one gets hurt if a baby doll is accidentally dropped on its head or a Nerf gun is fired at a “bad guy.”

365

parental-investment theory  a theory that stresses the evolutionary basis of many aspects of parental behavior, including the extensive investment parents make in their offspring

a theory that stresses the evolutionary basis of many aspects of parental behavior, including the extensive investment parents make in their offspring

To benefit from their protracted immature status, children must, of course, survive it, and their survival and development require that parents spend an enormous amount of time, energy, and resources in raising them (Bjorklund, 2007). Why are parents willing to sacrifice so much for the benefit of their offspring? According to parental-investment theory (Trivers, 1972), a primary source of motivation for parents to make such sacrifice is the drive to perpetuate their genes in the human gene pool, which can happen only if their offspring survive long enough to pass those genes on to the next generation.

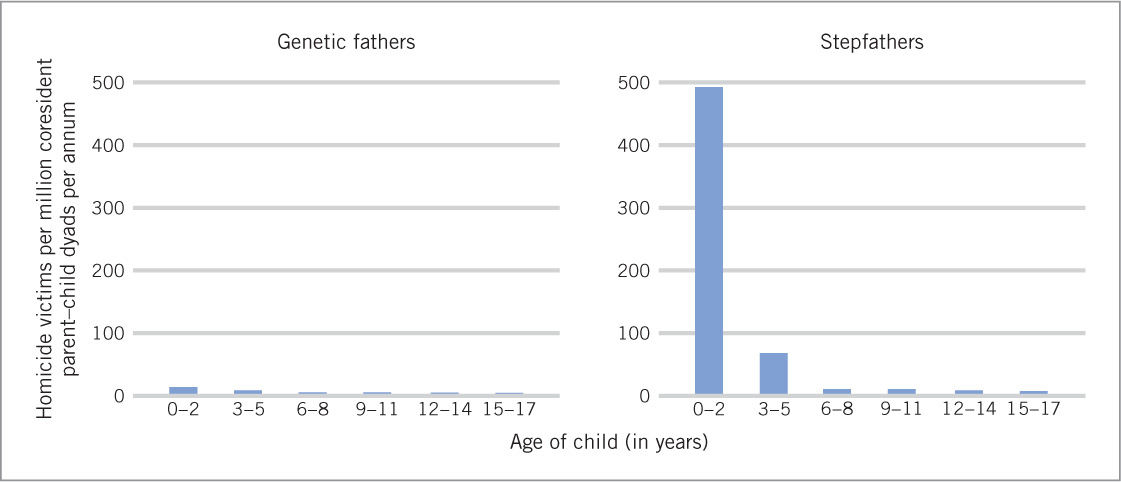

Parental-investment theory also points to a potential dark side of the evolutionary picture—the so-called Cinderella effect—which refers to the fact that rates of child maltreatment are considerably higher for stepparents than for biological parents. As Figure 9.3 shows, estimates of the rate of murder committed by step-fathers against children residing with them is hundreds of times higher than the rate for fathers and their biological children. Furthermore, in families in which both natural and stepchildren reside, abusive parents typically target their abuse toward their stepchildren (Daly & Wilson, 1996). Similar findings suggest that unintended child fatalities (e.g., drowning) are also more likely to occur in homes with a resident stepparent than in homes with no stepparent, suggesting that there is less commitment to protecting children in stepparent homes (Tooley et al., 2007). Although there are clearly many factors that contribute to these patterns, they are consistent with parent-investment theory; that is, because parenting is so costly, it is not, from an evolutionary point of view, worth investing in children who cannot contribute to the perpetuation of one’s own genes.

A clear implication of the evolutionary view of development is that radical departures from the species-typical environment could have negative consequences. It is well established that exposing young and prenatal animals of various species to stimulation that is outside the normal range for their species and age has adverse effects on their development (e.g., G. Gottlieb, 1992; Kenny & Turkewitz, 1986). For example, while developing inside the egg, bobwhite quails experience no light or visual stimulation. If a piece of the shell is removed, letting in light while the embryo develops, the species-typical behavior of the hatchlings is altered, disrupting normal development (Lickliter, 1995).

Could the same be true for humans? Neonatologist Heideliese Als and colleagues (2003) believe that we should be concerned about this question with regard to babies born prematurely. As discussed in Chapter 2, modern medicine has enabled increasing numbers of premature infants of ever-smaller sizes to survive. However, their first weeks or even months are spent in an environment that is radically different from the species-typical fetal environment. Instead of continued residence in the dark, relatively quiet womb, these babies find themselves in brightly lit, very noisy intensive-care units. Believing that many of the brain and behavioral problems common in premature infants may have to do with this atypical early environment, Als has advocated radical changes in newborn nurseries to simulate the womb environment, including reducing illumination and noise levels.

366

A related area of concern about potential negative effects of species-atypical stimulation is the current craze for providing extra prenatal stimulation that we discussed in Chapter 2. Our species evolved with a certain amount of stimulation available to the fetus in utero, and a substantial increase in prenatal stimulation might very well have negative consequences.

The Bioecological Model

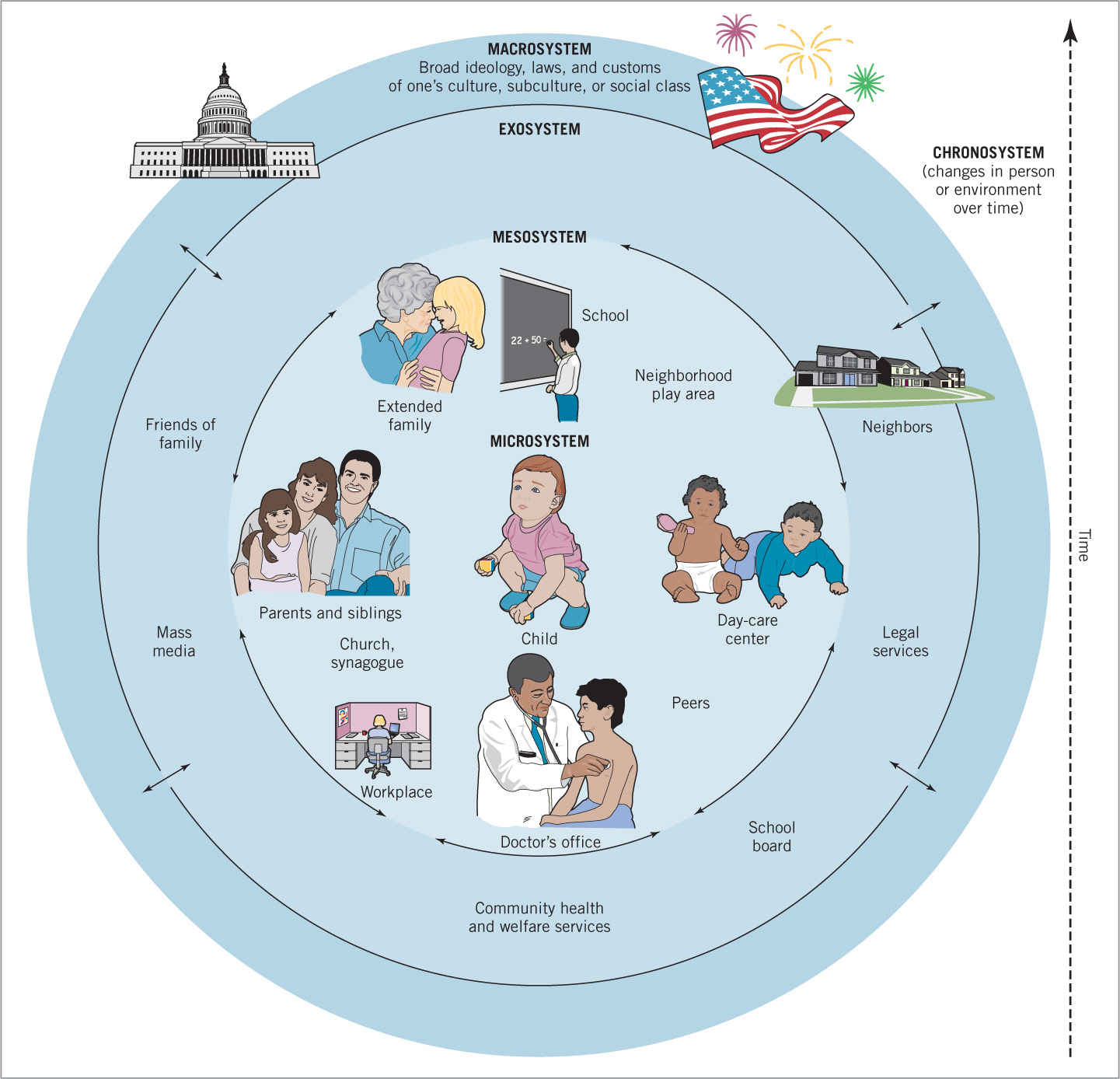

The most encompassing model of the general context of development is Urie Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). Bronfenbrenner conceptualizes the environment as “a set of nested structures, each inside the next, like a set of Russian dolls” (1979, p. 22). Each structure represents a different level of influence on development (Figure 9.4). Embedded in the center of the multiple levels of influences is the individual child, with his or her particular constellation of characteristics (genes, gender, age, temperament, health, intelligence, physical attractiveness, and so on).

Over the course of development, these individual characteristics interact with the environmental forces present at each level. The different levels vary in how immediate their effects are, but Bronfenbrenner emphasizes that every level, from the intimate context of a child’s nuclear family to the general culture in which the family lives, has an impact on that child’s development. Note that each of the levels depicted in Figure 9.4 is labeled as a “system,” emphasizing the complexity and interconnectedness of what goes on in each one. This theory is ecological in the sense that, just as in the study of the ecology of other living things, it considers how multiple levels of context influence outcomes. It just happens that instead of the soil microbes or natural predators that might be the relevant ecological contexts for plants or nonhuman animals, the ecological systems influencing children range from families to neighborhoods to governments.

367

microsystem  in the bioecological model, the immediate environment that an individual personally experiences

in the bioecological model, the immediate environment that an individual personally experiences

The first level in which the child is embedded is the microsystem—the activities, roles, and relationships in which the child directly participates over time. The child’s family is a crucial component of the microsystem, and its influence is predominant in infancy and early childhood. The microsystem becomes richer and more complex as the child grows older and interacts increasingly often with peers, teachers, and others in settings such as school, neighborhood, organized sports, arts, clubs, religious activities, and so on.

368

Bronfenbrenner stresses the bidirectional nature of all relationships within the microsystem. For example, the parents’ marital relationship can affect how they treat their children, and their children’s behavior can, in turn, have an impact on the marital relationship. A good, supportive marital relationship helps parents interact more sensitively and effectively with their children (P. A. Cowan, Powell, & Cowan, 1998; Cox et al., 1989), but a chronically fussy baby can create friction and even damage the relationship between parents (Belsky, Rosenberger, & Crnic, 1995).

mesosystem  in the bioecological model, the interconnections among immediate, or microsystem, settings

in the bioecological model, the interconnections among immediate, or microsystem, settings

The second level in Bronfenbrenner’s model is the mesosystem, which encompasses the connections among various microsystems, such as family, peers, and schools. Supportive relations among these contexts can benefit the child. For example, children’s academic success is facilitated when their parents value scholastic endeavors and have positive contact with their teachers (Luster & McAdoo, 1996; Stevenson, Chen, & Lee, 1993) and when their peers encourage academic achievement (Steinberg, Darling, & Fletcher, 1995). When connections in the mesosystem are nonsupportive, negative outcomes are more likely.

exosystem  in the bioecological model, environmental settings that a person does not directly experience but that can affect the person indirectly

in the bioecological model, environmental settings that a person does not directly experience but that can affect the person indirectly

The third level of social context, the exosystem, comprises settings that children may not directly be a part of but that can still influence their development. Their parents’ workplaces, for example, can affect children in many ways, from the employer’s policies about flexible work hours, parental leave, and on-site child care to the general atmosphere in which parents work. Parents’ enjoyment or dislike of their work can affect the emotional relationships within the family (Greenberger, O’Neil, & Nagel, 1994). Even something as seemingly remote from the child as the financial success or failure of a parent’s employer can be crucial: job loss, for example, is related to abusive or neglectful parenting (Emery & Laumann-Billings, 1998).

macrosystem  in the bioecological model, the larger cultural and social context within which the other systems are embedded

in the bioecological model, the larger cultural and social context within which the other systems are embedded

The outer level of Bronfenbrenner’s model is the macrosystem, which consists of the general beliefs, values, customs, and laws of the larger society in which all the other levels are embedded. It includes the general cultural, subcultural, or social-class groups to which the child belongs. Cultural and class differences permeate almost every aspect of children’s lives, including differences in beliefs about what qualities should be fostered in children and how best to foster them.

Cultural influences are apparent even in the earliest memories reported by adults in different parts of the world. In a cross-cultural study (Q. Wang, 2006), European Americans reported memories from an earlier age than did Taiwanese participants, and their memories focused on specific events and their own role in those events. In contrast, the Taiwanese participants more often described everyday events and emphasized the role of other people in the recalled events. Presumably, these differences reflect cultural values that influence what parents encourage their children to talk about, especially with respect to the relative value of focusing on oneself or on others.

chronosystem  in the bioecological model, historical changes that influence the other systems

in the bioecological model, historical changes that influence the other systems

Finally, Bronfenbrenner’s model also has a temporal dimension, which he has referred to as the chronosystem. In any given society, beliefs, values, customs, technologies, and social circumstances change over time, with consequences for children’s development. For example, as a result of technological advances that gave rise to the “digital age,” children today have access to a vast realm of information and entertainment unimaginable to previous generations. In addition, the impact of environmental events depends on another chronological variable—the age of the child. For example, divorce has different effects on toddlers and teens; it may make both of them unhappy, but young children are more likely to have the extra burden of thinking that the divorce is their fault (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992). Another important aspect of the temporal dimension, which we have noted on several occasions, is the fact that as children get older, they take an increasingly active role in their own development, making their own decisions about their friends, activities, and environments. As Box 9.2 on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (pages 370–371) suggests, the chronosystem can even be a factor in developmental disorders.

369

BETTMANN/CORBIS

RICHARDHUTCHINGS/PHOTOEDIT

To illustrate the richness of the bioecological model for thinking about and investigating child development, we will consider three examples in which the interactions among multiple levels of the model are particularly clear and relevant: child maltreatment, children and the media, and SES and development.

Child Maltreatment

child maltreatment  intentional abuse or neglect that endangers the well-being of anyone under the age of 18

intentional abuse or neglect that endangers the well-being of anyone under the age of 18

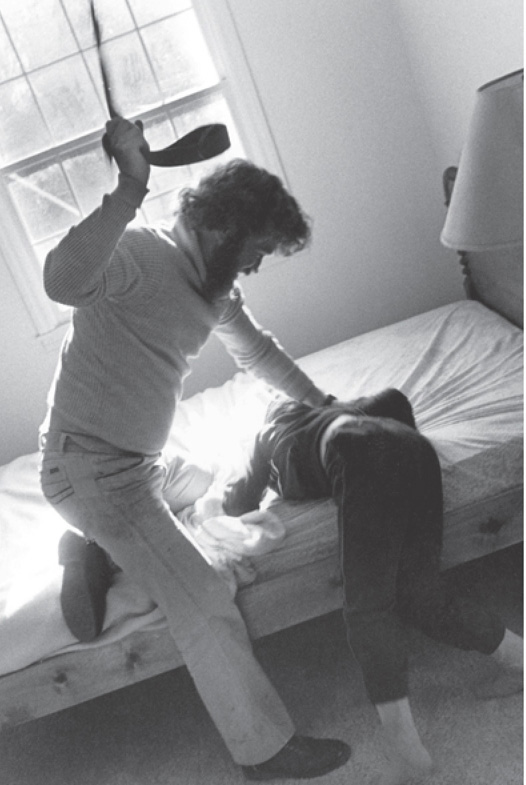

One of the most serious threats to children’s development in the United States is child maltreatment, defined as intentional abuse or neglect that endangers the well-being of anyone younger than 18. In 2011, roughly 681,000 children were confirmed to be victims of child maltreatment (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families, 2012). The majority of cases involved maltreatment by parents, more often mothers. The victims included nearly equal numbers of girls and boys. The highest rate of victimization was for infants younger than 1 year: 21.2 out of every 1,000 U.S. infants in this age group were maltreated in 2011. More tragic still, more than 1,500 children—most of them younger than 4—were killed by a parent or parents. Consistent with the bioecological model, a variety of factors, including characteristics of the child, the parents, and the community, have been shown to be involved in the causes and consequences of child abuse.

Causes of maltreatment At the level of the microsystem, certain characteristics of parents increase the risk for maltreatment (Emery & Laumann-Billings, 1998). Among these are low self-esteem, strong negative reactions to stress, and poor impulse control. Parental alcohol and drug dependence also increase the probability of maltreatment. So does an abusive spousal relationship: mothers who are abused by their partner are more likely to abuse their children. In addition, certain characteristics of children—including low birth weight, physical or cognitive challenges, and difficult temperament—are associated with increased risk for parental abuse (e.g., Bugental & Happaney, 2004).

370

Box 9.2: individual differences

Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)  a syndrome that involves difficulty in sustaining attention

a syndrome that involves difficulty in sustaining attention

Many developmental disorders can be profitably examined with the different levels of the bioecological model in mind. Influences and interventions from different levels can make it easier or harder for children to manage the challenges they face. A good case in point is attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Although the term “ADHD” is relatively new, the syndrome—variously labeled as “hyperactivity,” “minimal brain dysfunction,” and “attention-deficit disorder” (ADD)—has long been recognized. Children with ADHD tend to be of normal intelligence and do not typically show serious emotional disturbances. However, they have difficulty sticking to plans, following rules and regulations, and persevering on tasks that require sustained attention (especially ones they find uninteresting). Many are hyperactive, constantly fidgeting, drumming on their desks, and moving around. Children with ADHD typically have difficulty acquiring academic skills, such as reading and writing, since these skills require focusing attention for prolonged periods. Many also have problems suppressing aggressive reactions when they are frustrated. All these symptoms seem to reflect an underlying difficulty in inhibiting impulses to act (Barkley, 1997). The difficulty is greatest when interesting distractors are present.

An analysis of data collected by the Centers for Disease Control for 2011–2012 suggests that 6.4 million children aged 4 to 17 received a diagnosis of ADHD at some time in their life. In other words, roughly 11% of school-aged children in the United States today have been given a diagnosis of ADHD. This represents a 16% increase in ADHD diagnoses for this age group since 2007 and a whopping 41% increase over the past decade. Even more remarkably, 20% of high school boys have been given a diagnosis of ADHD at some point in their lives, compared with 10% of high school girls. This diagnostic differential may be attributable to the fact that boys with ADHD are more likely than girls to engage in disruptive behaviors that lead to their problem being diagnosed (Gaub & Carlson, 1997). As with autism spectrum disorder (discussed in Chapter 3), it is currently unclear whether the steep increase in rates of diagnosis of ADHD reflects an actual increase in prevalence, increased awareness of the disorder, changing standards for ADHD diagnoses, or all of the above.

The causes of ADHD are quite varied. Genetic factors clearly play a role. If one identical twin has ADHD, the odds are about 50% that the other twin does too, a rate roughly 10 times that among children in general (Silver, 1999). In addition, ADHD in adopted children is associated with ADHD in the biological parent but not in the adoptive parent (Rhee et al., 1999). Indeed, heritability for ADHD is greater than any other developmental disorder, with the possible exception of autism spectrum disorder.

Environmental factors in the microsystem also influence the development of ADHD. For instance, prenatal exposure to alcohol, which can affect brain development (Chapter 2), is associated with the development of ADHD (Milberger et al., 1997). Parents’ behavior toward their children may contribute to the early development of ADHD, as shown by a large study with 5-year-olds, half of whom had been of low birth weight (Tully et al., 2004). Those low-birth-weight children whose mothers expressed a high degree of warmth for them (“He’s my ray of sunshine,” “She’s a delight”) were less likely than children of less warm mothers to show symptoms of ADHD. However, causal links can be difficult to determine because, as we have noted on numerous occasions, developmental risks tend to cluster together.

Current treatment for ADHD involves agents in the microsystem (the family doctor), the exosystem (the drug industry), and the macrosystem (the government). The most common approach taken by physicians is to prescribe stimulant medications, such as Ritalin. Although it seems paradoxical that stimulants could help children who are already overly active, they improve symptoms in 70% to 90% of children for whom they are prescribed. The reason is that the brain systems in these children are actually underaroused; the children’s restless and sometimes disruptive behavior is actually an attempt to wake the brain up. Appropriate medication, which stimulates neurotransmitter systems, allows children with ADHD to focus their attention better and to be less distractible. This leads to improved academic achievement, better relationships with classmates, and reduced activity levels (Barbaresi et al., 2007a, 2007b).

It is important to realize that the benefits of Ritalin continue only as long as children take the medication. Longer-lasting gains require not only medication but also behavioral treatments. A large-scale clinical trial found that high-quality medication management (with careful dosing and extensive follow-up) paired with intensive behavioral treatments (in this case, focused on behavioral management in the context of sports and social skills) led to more positive outcomes than did either medication or behavioral intervention alone (P. S. Jensen et al., 2001). Parents’ disciplinary practices also had an impact on the efficacy of these treatments in this study. In particular, ADHD treatment had the greatest impact on children’s behavior in school when parents were able to improve their previously negative or ineffective parenting behavior. These findings highlight the importance of considering the impact of multiple systems on developmental outcomes.

The availability of medications helpful to those with ADHD is, of course, the result of a perception on the part of drug companies that they can produce, sell, and make a profit from a drug targeted for this problem. It also depends on the medication’s receiving a favorable evaluation from the FDA, based on research to determine the drug’s efficacy and potential side effects. Thus, the fate of a child in need of medication could be quite different, depending on factors far outside the influence of his or her family.

But would any intervention be necessary in the first place if it were not the case that every school-aged child is expected to spend a substantial amount of time on most days sitting quietly at a desk concentrating on tasks that he or she may have little interest in? Pointing to the highest level of the bioecological model—the chronosystem—many experts have suggested that ADHD may have emerged as a serious problem only in recent times—specifically, only since the advent of compulsory schooling. Before then, an individual who had attentional difficulties that would have posed problems in a classroom might very well have been able to function successfully in an environment where such difficulties were inconsequential, even unnoticed.

Child maltreatment tends to be associated with additional factors in the mesosystem and exosystem that increase stress on parents. Many of these factors are related to low family income. They include high levels of unemployment, inadequate housing, and community violence (Emery & Laumann-Billings, 1998; Lynch & Cicchetti, 1998).

371

Often a particularly important exosystem contributor to child maltreatment is a family’s social isolation and lack of social support (more common in lower-income families). Such isolation may have multiple causes—mistrust of other people, a lack of the social skills needed to maintain positive relationships, frequent moves from place to place because of economic factors, or living in a community characterized by violence and transience. The importance of social support is highlighted by the fact that impoverished parents are less likely to maltreat their children if they live in a neighborhood in which there is a prevailing sense of community, with neighbors who care about and help one another (Belsky, 1993; Coulton et al., 1995; Garbarino & Kostelny, 1992).

372

Consequences of maltreatment The consequences of child maltreatment are manifested primarily in the microsystem (although they can extend to, and be moderated by, factors in the mesosystem and exosystem such as child-protection policies and agencies). In comparison with other children, maltreated children have less secure relationships with their parents, show less empathy for other people, and have lower self-esteem (Cicchetti & Toth, 1998; Main & George, 1985; M. Smith & Walden, 1999). In elementary school, maltreated children are more aggressive and have more conflict with their peers (Bolger & Patterson, 2001; L. A. McCloskey & Stuewig, 2001). Later on, they have difficulty maintaining friendships (Parker & Herrera, 1996; Rogosch, Cicchetti, & Aber, 1995; Salzinger et al., 2001). At school, maltreated children are often anxious and inattentive and overly dependent on their teachers for approval and support. They are more than twice as likely as other children to fail a grade (Eckenrode, Laird, & Doris, 1993; Erickson et al., 1989).

We can further examine the effects of maltreatment at an even more micro level. In our earlier discussion of the hostile attributional bias, we noted that children who are the victims of physical abuse show a heightened response to anger cues. This heightening is observed in behavioral responses, in brain responses such as event-related potentials, or ERPs (e.g., Pollak et al., 1997), and in physiological responses, including heart rate and skin conductance (Pollak et al., 2005). Although such responses might be maladaptive in many social situations, leading children to misinterpret or overreact to emotional cues, an ecological perspective suggests that overattention to negative emotions might be highly adaptive for children growing up in a home marked by threat and danger. By considering children’s responses to their environments as adaptive in some contexts, but maladaptive in others, an ecological perspective may help explain why maltreatment has the particular constellation of effects that it does, as well as which interventions might be most effective (e.g., Frankenhuis & de Weerth, 2013). Of course, the ideal situation would be to prevent child maltreatment altogether. (For a promising approach to preventing child abuse, see Box 9.3).

Children and the Media: The Good, the Bad, and the Awful

Another good illustration of the multiple levels in which children’s development is embedded is the impact of various media—television programs, movies, video games, and popular music. In terms of the bioecological model, media are situated in the exosystem, but they are subject to influences from the chronosystem, as indicated earlier; from the macrosystem (including cultural values and government policies); from other elements in the exosystem (such as economic pressures); and from the microsystem (such as parental monitoring). All these factors are at play every time children tune in or boot up.

Early on, when children’s in-home screen viewing was mostly limited to TV, some educationally oriented television programming for young children was shown to have beneficial effects (Huston & Wright, 1998). Most notably, watching Sesame Street was associated with increases in young children’s vocabulary and helped prepare them for school entry, with some positive effects persisting even through high school (D. R. Anderson et al., 2001; Rice et al., 1990). However, as you read in Chapter 6 (Box 6.3: iBabies: Technology and Language Learning), some “educational” DVDs actually have negative effects on language development.

As screens become ever more pervasive, moving from living rooms to bedrooms to children’s pockets, concerns about screen time continue to mount. American children now spend more time involved in using screen media than in any other activity besides sleeping. This fact was documented by a national survey conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation (Rideout, Foehr, & Roberts, 2010). Media usage is increasing at an incredible rate; 8- to 18-year-olds upped their average screen time by more than an hour just in the past = years, from an average of 6 hours 21 minutes in 2005 to 7 hours 38 minutes in 2010. Use of every type of electronic media has increased during that time, fueled by social networking (see Box 13.2, pages 529–530), the availability of television programming streamed on demand (rather than presented at a fixed time, as in the past), and an explosion in the use of portable electronics. In 2012, a Pew survey revealed that 37% of American teens have smartphones, and 23% have a tablet computer (Madden et al., 2013). Three out of every four teens use their mobile devices to access the Internet. Even very young children are active participants in this media immersion: children 6 years and younger devote more time to entertainment media than to reading, being read to, and playing outside combined (Rideout et al., 2003).

373

Box 9.3: applications

Preventing Child Abuse

Given the multiple factors that contribute to child maltreatment, preventing or ameliorating the problem of abuse is extremely difficult. However, one very promising intervention program was developed from research financed by federal funding agencies at the macrosystem level and is carried out at the microsystem level.

The program, reflecting a social cognition perspective, was designed and implemented by Daphne Bugental and her colleagues, who found that many abusive parents have inappropriate models of their relationship with their children. They tend to see themselves and their children as locked in a power struggle—a conflict in which they view themselves as the victims (Bugental, Blue, & Cruzcosa, 1989; Bugental & Happaney, 2004). Thus, they might interpret their baby’s prolonged crying as evidence that the baby is mad at them, and they might think that a child who continues to beg for a withheld toy or treat is intentionally trying to subvert their authority.

The goal of this program was to help parents at risk for abusing their children achieve more realistic interpretations of their difficulties in caring for their children (Bugental et al., 2002). As we discussed in Chapter 2, some children are particularly at risk for abuse, including those born preterm or with other medical complications that make parenting especially challenging. The intervention for families with such children involved frequent home visits in which parents were asked to give examples of recent problems they had had with their children and to indicate what they thought had been the cause of the problem. They were then led to identify a cause that did not focus blame on the children (i.e., something other than deliberate misbehavior by their children), as well as to come up with potential strategies for solving the problem.

A particularly important factor in assessing this program is that at-risk families were randomly assigned to the intervention condition or to two comparison conditions. Thus, any difference in outcomes could not be due to initial differences among the groups.

The program was remarkably successful: the prevalence of physical abuse in the intervention group was only 4%, compared with around 25% in the two comparison groups. This intervention program, targeted at the microsystem level, suggests that home-visiting programs that focus on altering parents’ cognitive interpretations have a high potential for preventing physical abuse. And, consistent with the parent-investment theory discussed earlier in this chapter in the context of evolutionary psychology, the program led parents to begin to invest more caregiving in their at-risk (preterm) infants (Bugental, Beaulieu, & Silbert-Geiger, 2010). As parents developed a greater understanding of the needs—and the potential—of their infants, they subsequently increased their investment in their offspring, who later showed substantial health benefits.

374

Concerns About Children’s Exposure to MediaThe nature and amount of children’s media exposure have aroused a variety of concerns, ranging from the possible effects of media violence and pornography to those of isolation and inactivity.

MEDIA VIOLENCE Foremost among the concerns that have been raised is fear that a steady diet of watching violent television shows, playing violent video games, and listening to music with violent lyrics will cause children to behave violently. The concern originally arose from the fact that television was awash in violence, as indexed by a comprehensive study reporting that 61% of programs on television between 1994 and 1997 contained episodes of violence (B. J. Wilson et al., 1997). The prevalence of TV violence has since intensified, with the six major networks averaging 4.4 violent incidents per hour during prime-time viewing in the 2005–2006 season (Parents Television Council, 2007). Furthermore, aggression in television programs and movies tends to be glamorized and trivialized—particularly the violence perpetrated by heroes, who are rarely punished or condemned for their actions.

Extensive reviews of the vast amount of research on this issue have led researchers to conclude that the scientific debate about whether media violence increases aggression and violence is over. The evidence is clear that media violence has negative effects on children. In 2009, a policy statement by the American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Communications Media began by stating that “exposure to violence in media, including television, movies, music, and video games, represents a significant risk to the health of children and adolescents.”

Exposure to media violence has an impact in four different ways (C. A. Anderson et al., 2003). First, seeing actors engage in aggression teaches aggressive behaviors and inspires imitation of them, as you saw earlier in this chapter in the discussion of Bandura’s studies with Bobo. Second, viewing aggression activates the viewer’s own aggressive thoughts, feelings, and tendencies. This heightened aggressive mindset makes it more likely that the individual will interpret new interactions and events as involving aggression and will respond aggressively. Furthermore, when aggression-related thoughts are frequently activated, they may become part of the individual’s normal internal state. Third, media violence is exciting and arousing for most youth, and their heightened physiological arousal makes them more likely to react violently to provocations right after watching violent films. Finally, frequent long-term exposure to media violence gradually leads to emotional desensitization—a reduction in the level of unpleasant physiological arousal most people experience when observing violence. Because this arousal normally helps inhibit violent behavior, emotional desensitization can render violent thoughts and behaviors more likely.

375

PHYSICAL INACTIVITY Another concern has to do with the fact that a child who is glued to a screen is not outside playing or otherwise engaging in robust physical activity. In addition, the thousands of TV commercials with which children are bombarded every year (at an advertiser cost of billions of dollars per year) consist largely of advertisements for sugary cereals, candy, and fast-food restaurants. The sedentary nature of screen time, combined with the onslaught of commercials encouraging the consumption of sweet, fatty foods, have been linked to the recent increase in childhood obesity discussed in Chapter 3. Indeed, when a child has a TV in the bedroom—as do more than 70% of 8- to 18-year-olds (Rideout, Foehr, & Roberts, 2010)—the child’s risk of obesity increases by 31% (Dennison et al., 2002).

EFFECTS ON ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT According to a study by the Kaiser Family Foundation, there is a strong relationship between media use and school grades (Rideout et al., 2010). For example, children who are heavy users of screen media (more than 16 hours per day) are far more likely to report fair/poor grades (Cs or below) than are those who are moderate users (3 to 16 hours per day) or light users (less than × hours per day). Of course, there are many other confounding factors that might underlie a link between media usage and grades, such as generally poor parental supervision, or a family culture (parents included) that deemphasizes reading and other academic pursuits in favor of screen time.

However, one cleverly designed study was able to draw causal conclusions about the relation between video games and school achievement (Weis & Cerankosky, 2010). Boys in the 1st through 3rd grades who did not already own a video game console were randomly assigned to an experimental group, whose members were given a console at the beginning of the study, or to a comparison group, whose members were, in the name of fairness, given a console after the study was completed. The boys who received the game console at the beginning of the study subsequently spent less time on after-school academic pursuits than the boys in the comparison group, and 4 months into the study, performed more poorly on measures of literacy and had a higher rate of teacher-reported academic problems than did the comparison group. Boys who spent the most time with the games showed the poorest academic outcomes.

SOCIAL INEQUITIES Another area of concern centers on the possibility that socioeconomic inequalities will be exacerbated by the “digital divide”—that is, unequal access to and use of computers as a function of SES. Most children have some degree of access to computers at school, but there are great differences between low-SES and high-SES families in terms of the likelihood that computers are available in their homes. Furthermore, higher-SES families are more likely to have newer, more powerful computers and to have more than one of them. Thus, children from higher-SES families are far more likely to be able to use computers to do homework and to use the Internet than are children from poorer families. The disparity in access to computers is less extreme at school, where computers are used extensively in classrooms even in low-SES neighborhoods.

376

PORNOGRAPHY A serious concern for many parents is children’s exposure to pornography on television and the Internet, whether inadvertent or intentional. Online pornography is particularly problematic because of its ready availability. On average, American children first encounter pornography on the Web at the age of 11 (Ropelato, 2009). Research suggests that exposure to pornography can make children and teens more tolerant of aggression toward women, as well as more accepting of premarital and extramarital sex (Greenfield, 2004).

Of special concern is pornography featuring children. Child pornography is a multibillion-dollar industry and among the fastest-growing criminal segments on the Web (Federal Bureau of Investigation, n.d.). Today, pedophiles commonly use the Web, including chat rooms, to share illegal photographs of children and to lure children into sexual relationships.

The most effective weapons against the various negative effects of media on children operate at the microsystem level, with parents exercising control over their children’s access to undesirable media, and at the macrosystem level, with legal controls and government programs designed to minimize the negative features of the media with which children interact. Effective control is complicated, however, by free speech concerns and, in the case of Internet pornography, the global nature of the problem.

SES and Development

As we have frequently noted, the SES of their families has profound effects on children’s development. These effects originate at every level of the bioecological model. In the microsystem, children are affected by the nature of their family’s housing and their neighborhood, and in the mesosystem, by the condition of their school and the quality of their teachers. Exosystem influences include the nature of the parents’ employment or lack of employment. Macrosystem factors include the government policies that affect employment opportunities and establish programs like Project Head Start geared to low-income families.

Chronosystem factors also come into play with respect to changes over time in the kind and number of jobs that are available. For example, in the United States, the number of well-paying manufacturing jobs has been shrinking for many years, ravaging whole communities with skyrocketing unemployment. The shrinking tax base in those communities, and in others affected by the economic downturn of the past several years, has resulted in fewer resources to support schools, health care, and other community resources important for developing children.

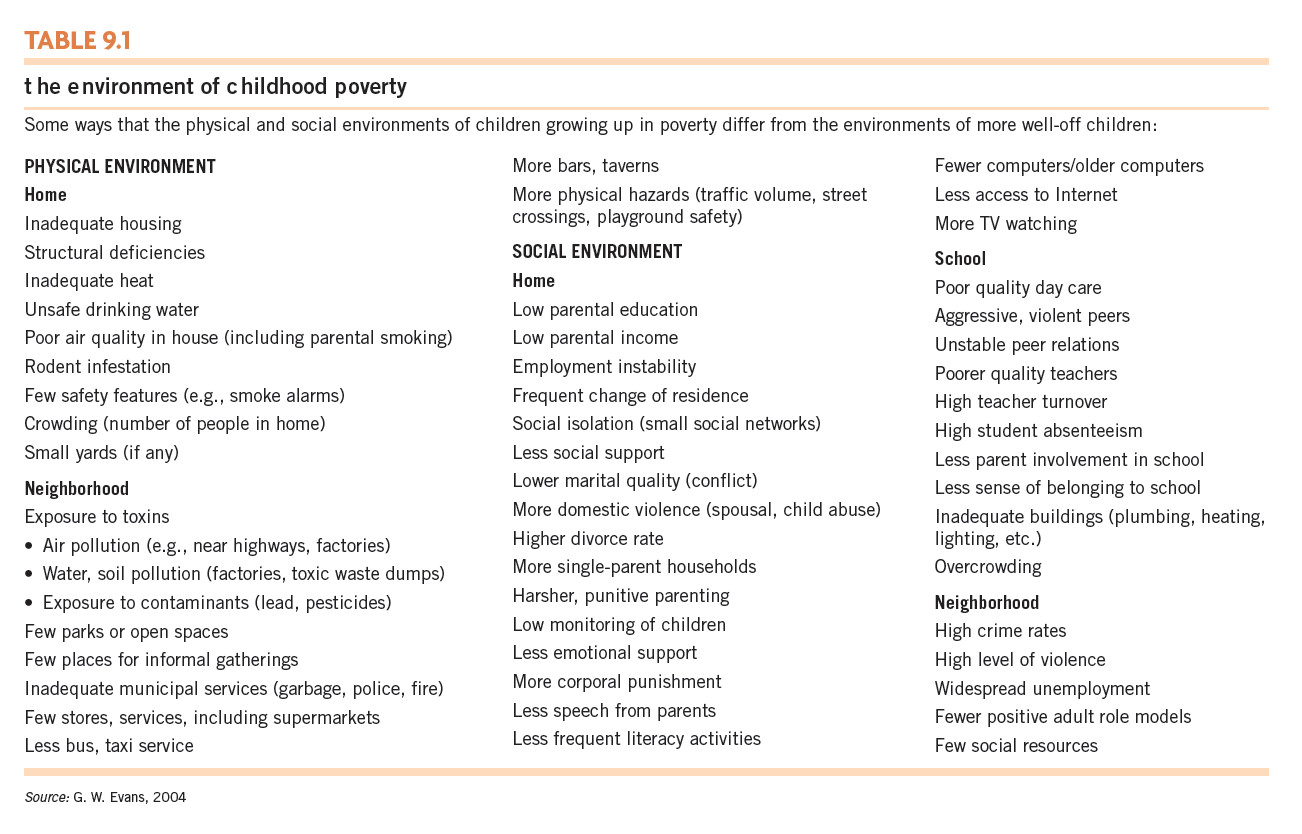

The Pervasive Effects of Poverty In many of our discussions throughout this book, we focus on a number of factors that affect the development of children living in poverty. However, the factors we discuss are only the tip of the iceberg. Table 9.1 lists a wide variety of ways that the environment of poor children in the United States differs from that of more affluent children (summarized from G. W. Evans, 2004). Many of the items in the table will be familiar to you, but you may never have considered some of the others. As you look over the table, think about how these various aspects of impoverished environments interact and what their cumulative impact might be. Also, consider how the many detrimental factors listed in the table relate to the different levels of the bioecological model, from government priorities and policies to the physical health of the individual child growing up in poverty.

377

As you look over the table, you should also keep in mind two points from our discussion of the multiple-risk model in Chapter 2. First, it is the accumulated exposure to multiple environmental risk factors that is crucial (G. W. Evans, 2004). A child whose parents are neglectful might cope reasonably well, but doing so would be more difficult if the child also goes to a poor-quality school in a dangerous neighborhood. Second, as discussed in Chapters 10 and 11, individual children differ with respect to how susceptible they are to environmental influences, both positive and negative (Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2002).

Because many specific effects of poverty on development are discussed throughout the book, we will not feature them here but, instead, will examine a developmental effect of SES that often goes unnoticed: the costs of affluence.

The Costs of Affluence Contrary to popular assumption, growing up in highly affluent families can have negative effects on development. The stereotype of the “poor little rich kid” seems to have some basis in fact. For example, compared with inner-city adolescents, affluent youth report higher levels of anxiety, greater depression, and more use of illicit substances (cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs) (Luthar, 2003). Although adolescents’ use of illicit substances is linked with depression and anxiety, it is also associated with popularity, suggesting that peer influences may actively promote this behavior.

378

In attempting to account for these findings, Luthar and Becker (2002) note that affluent parents tend to pressure their children to excel both academically and in extracurricular activities. At the same time, these parents often provide their children with little support. For example, because of the career demands of the parents and their children’s many after-school activities, family time is diminished in many high-income families (Luthar & Latendresse, 2005; Rosenfeld & Wise, 2000). In addition, when both parents have careers, many preteens from upper-income families are home alone after school, unsupervised, for several hours a week (Capizzano, Tout, & Adams, 2002).

A rather remarkable fact is that, in a national survey, U.S. teens whose family income was fairly low reported higher feelings of closeness with their mothers and fathers than did those whose family income was much higher (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 1999). In addition, the level of happiness reported by youth is not directly related to their family’s level of affluence (Csikszentmihalyi & Schneider, 2000).

Current Perspectives

The three theoretical positions discussed in this section have all made valuable contributions to developmental science by placing individual development in a much broader context than is typically done in mainstream psychology. All of them challenge researchers to look beyond the lab—far beyond it.

The primary contribution of ethology and evolutionary psychology comes from the emphasis on children’s biological nature, including genetic tendencies grounded in evolution. Evolutionary psychology has provided fascinating insights into human development, but it has also come in for serious criticism. One frequent complaint is that, like psychoanalytic theories, many of the claims of evolutionary psychologists are impossible to test. Often, a behavioral pattern that is consistent with an evolutionary account is at least equally consistent with social learning or some other perspective. Finally, evolutionary-psychology theories tend to overlook one of the most remarkable features of human beings, a feature strongly emphasized by Bronfenbrenner—our capacity to transform our environments and ourselves.

379

Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model has made an important contribution to our thinking about development. His emphasis on the broad context of development and the many different interactions among factors at various levels has highlighted how complex the development of every child is. The main criticism of this model is its lack of emphasis on biological factors.

What is the relevance of ecological theories to Kismet’s design? Evolution is basically irrelevant to it. Evolutionary change does not apply to individual development, and, without the possibility for reproduction, it simply cannot occur.

With respect to the bioecological model, Kismet is developing in an extremely limited microsystem—Cynthia Breazeal’s lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology—populated with a relatively small number of people. It has no mesosystem at present, although that could change in the future. This fact makes Kismet’s experience quite different from that of most human children. Kismet could be affected by the macrosystem at any time, if changes in research priorities of the federal government cut off funding for the project. In terms of the chronosystem, such a remarkable robot was unimaginable until recently, and even more remarkable ones are currently being developed to follow in Kismet’s footsteps.

It is interesting that the most difficult parallels to draw between Kismet’s development and that of children and theories of social development concern the larger context of human development. Part of what is unique about the human species is the fact that every individual is embedded in multiple layers of human interactions, institutions, traditions, and history.

review:

The theories we have grouped under the label “ecological theories” examine development in a much broader context than those found in other theoretical approaches. Theories of development based on ethology and evolutionary psychology emphasize the influence of the evolutionary history of the human species on the development of individual children. Parental-investment theory proposes that the perpetuation of one’s genes underlies the enormous effort that parents invest in raising their children.

Other evolutionary theories emphasize the adaptive function of prolonged immaturity in the development of human children. Urie Bronfenbrenner’s highly influential bioecological model conceptualizes the environment in which children develop as a set of nested systems, or contexts. The systems range from aspects of the environment that the individual child directly experiences on a daily basis to the broader society and historical time in which the child lives.