508

Peer Relationships

509

- What Is Special About Peer Relationships?

- Friendships

- Early Peer Interactions and Friendships

- Developmental Changes in Friendship

- The Functions of Friendships

- Effects of Friendships on Psychological Functioning and Behavior over Time

- Children’s Choice of Friends

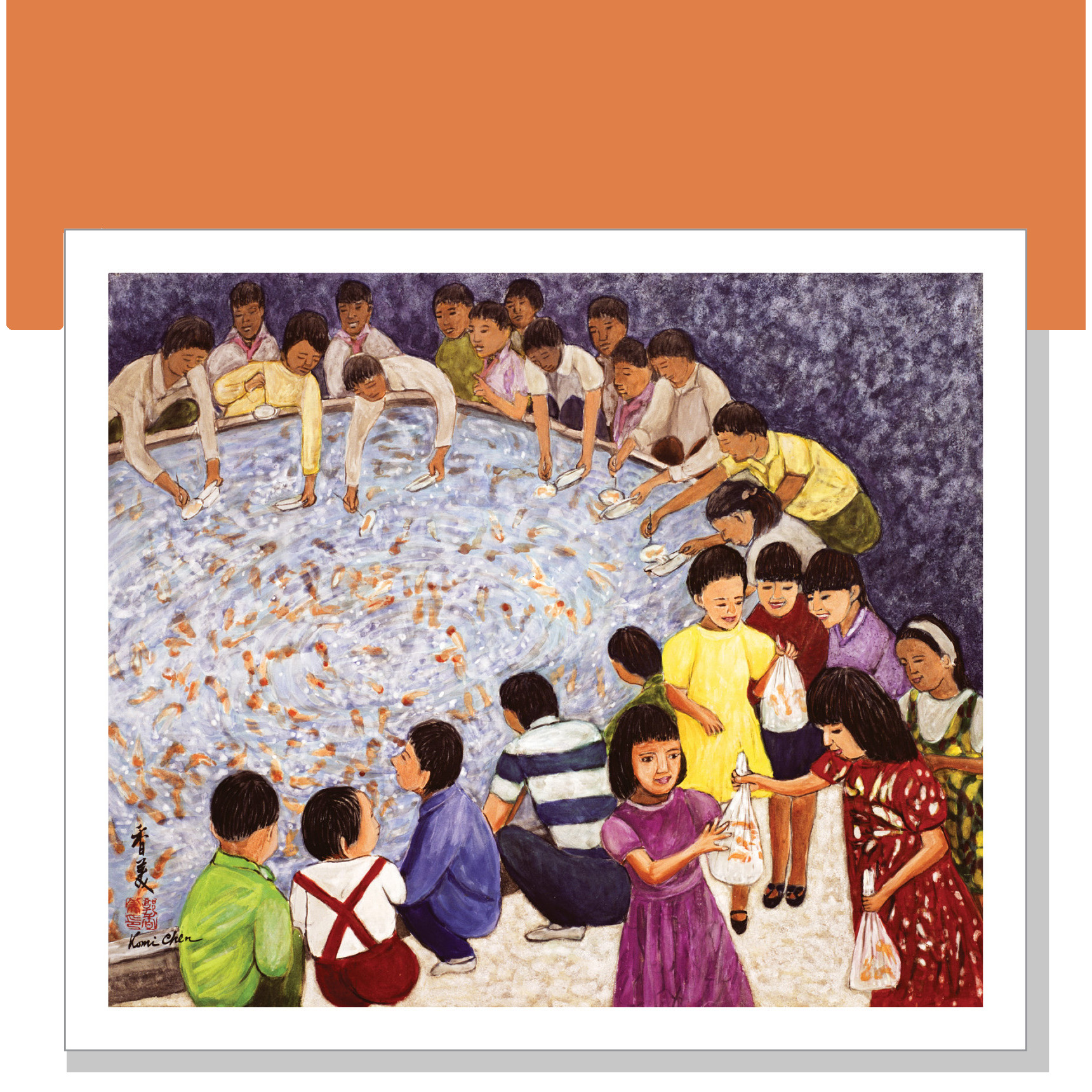

- Box 13.1: Individual Differences Culture and Children’s Peer Experience

- Review

- Peers in Groups

- The Nature of Young Children’s Groups

- Cliques and Social Networks in Middle Childhood and Early Adolescence

- Cliques and Social Networks in Adolescence

- Box 13.2: A Closer Look Cyberspace and Children’s Peer Experience

- Negative Influences of Cliques and Social Networks

- Romantic Relationships with Peers

- Review

- Status in the Peer Group

- Measurement of Peer Status

- Characteristics Associated with Sociometric Status

- Box 13.3: Applications Fostering Children’s Peer Acceptance

- Stability of Sociometric Status

- Cross-Cultural Similarities and Differences in Factors Related to Peer Status

- Peer Status as a Predictor of Risk

- Review

- The Role of Parents in Children’s Peer Relationships

- Relations Between Attachment and Competence with Peers

- Quality of Ongoing Parent–Child Interactions and Peer Relationships

- Parental Beliefs

- Gatekeeping and Coaching

- Family Stress and Children’s Social Competence

- Review

- Chapter Summary

510

Themes

Nature and Nurture

Nature and Nurture

The Active Child

The Active Child

Continuity/Discontinuity

Continuity/Discontinuity

The Sociocultural Context

The Sociocultural Context

Individual Differences

Individual Differences

Research and Children’s Welfare

Research and Children’s Welfare

n Chapters 1 and 11, we described the plight of institutionalized orphans who, lacking consistent interaction with a caring adult, developed social, emotional, and cognitive deficits. After World War II, an interesting exception to this pattern was noted by Anna Freud—the daughter of Sigmund Freud—and Sophie Dann (1951/1972). They observed six young German-Jewish children who had been victims of the Hitler regime. Soon after these children were born, their parents were deported to Poland and killed. The children were subsequently moved from one refuge to another until, between the ages of approximately 6 and 12 months, they were placed in a ward for motherless children in a concentration camp. The care they received in this ward was undoubtedly compromised by the fact that their caregivers were themselves prisoners who were undernourished and overworked. Moreover, the rates of deportation and death among the prisoners were high, so it is likely that the children’s caregivers changed frequently.

n Chapters 1 and 11, we described the plight of institutionalized orphans who, lacking consistent interaction with a caring adult, developed social, emotional, and cognitive deficits. After World War II, an interesting exception to this pattern was noted by Anna Freud—the daughter of Sigmund Freud—and Sophie Dann (1951/1972). They observed six young German-Jewish children who had been victims of the Hitler regime. Soon after these children were born, their parents were deported to Poland and killed. The children were subsequently moved from one refuge to another until, between the ages of approximately 6 and 12 months, they were placed in a ward for motherless children in a concentration camp. The care they received in this ward was undoubtedly compromised by the fact that their caregivers were themselves prisoners who were undernourished and overworked. Moreover, the rates of deportation and death among the prisoners were high, so it is likely that the children’s caregivers changed frequently.

In 1945, approximately 2 to 3 years after the children’s arrival at the concentration camp, the camp was liberated; within a month, the six children were sent to Britain. After spending 2 months in a reception facility, the children, as a group, were sent to various shelters and then, finally, to a country house that had been converted to accommodate orphans.

Given the conditions of their early lives, it is not surprising that these children initially showed a variety of problem behaviors in their new home:

During the first days after arrival they destroyed all the toys and damaged much of the furniture. Toward the staff they behaved either with cold indifference or with active hostility, making no exception for the young assistant Maureen who had accompanied them from Windermere and was their only link with the immediate past. At times they ignored the adults so completely that they would not look up when one of them entered the room.…In anger, they would hit the adults, bite or spit…shout, scream, and use bad language.

(A. Freud & Dann, 1972, p. 452)

These children behaved quite differently among themselves, however. They obviously were deeply attached to one another, sensitive to one another’s feelings, and they exhibited almost a complete lack of envy, jealousy, and rivalry. They shared possessions and food, helped and protected one another, and admired one another’s abilities and accomplishments. The children’s closeness is reflected in this brief selection from Freud and Dann’s daily observations:

November 1945—John cries when there is no cake left for a second helping for him. Ruth and Miriam offer him what is left of their portions. While John eats their pieces of cake, they pet him and comment contentedly on what they have given him.…

December 1945—Paul loses his gloves during a walk. John gives him his own gloves, and never complains that his hands are cold.…

April 1946—On the beach in Brighton, Ruth throws pebbles into the water. Peter is afraid of the waves and does not dare to approach them. In spite of his fear, he suddenly rushes to Ruth, calls out: “Water coming, water coming,” and drags her back to safety.…

Freud and Dann concluded that the children, although aggressive and difficult for adults to handle, were “neither deficient, delinquent nor psychotic” (p. 473) and that their relationships with one another helped them to master their anxiety and develop the capacity for social relationships.

511

Freud and Dann’s observations provided some of the first evidence that relationships with peers can help very young children develop some of the social and emotional capacities that usually emerge in the context of adult–child attachments. Two decades later, similar findings were obtained in research with monkeys. As discussed in Chapter 10, Stephen Suomi and Harry Harlow raised laboratory monkeys in isolation from other monkeys from birth to 6 months of age. By the end of this period, the isolate monkeys had developed significant abnormalities in behavior, such as compulsive rocking and a reluctance to explore. Some of the isolate monkeys were subsequently placed with one or two normal, playful monkeys who were 3 months younger. Over the course of the next several months, the isolate monkeys’ abnormal behaviors diminished greatly, and they began to explore their environment and engage in social interactions, demonstrating that peers can provide some of the social and emotional experiences required for normal development in monkeys (Suomi & Harlow, 1972).

Findings such as these do not suggest that peers alone can produce optimal development in young children. However, they do suggest that peers can contribute to children’s development in meaningful ways. In fact, in Western societies, children’s relationships with other children—their friends and acquaintances at school and in the neighborhood—usually play a very important role in their lives. By middle childhood in the United States, for example, more than 30% of children’s social interactions involve peers (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 1998). As they grow older, children spend increasingly more time with peers and interact with a greater number of them. Thus, peer interactions are a context in which children develop social skills and test new behaviors, good and bad.

In this chapter, we consider the special nature of peer interactions and their implications for children’s social development. First, we discuss theoretical views on what makes peer interactions special. Then we look at friendships, the most intimate form of peer relationships, and consider questions such as: How do children’s interactions with friends differ from those with other peers (nonfriends)? How do friendships change with age? What do children get out of friendships and how do they think about them?

Next, we consider children’s relationships in the larger peer group. These relationships are discussed separately from friendships because they appear to play a somewhat different role in children’s development, particularly in regard to the provision of intimacy. We try to answer questions such as: What are the differences among children who are liked, disliked, or not noticed by their peers? Does children’s acceptance or rejection by peers have long-term implications for their behavior and psychological adjustment?

In our discussions of friendships as well as more general peer relationships, we will examine individual differences among children in their relationships with peers and the ways in which these differences may cause differences in development. In addition, we will focus on the influence that the sociocultural context has on peer relationships, the contributions that both nature and nurture make to the quality of children’s peer relationships, and the role of the active child in choosing friends and activities with peers. We will also consider the question of whether changes in children’s thinking about friendships exhibit continuity or discontinuity. Finally, as an example of research and children’s welfare, we will examine interventions to improve children’s interactions with other children.

512